By Raphael Baladad

Since assuming office, President Rodrigo Duterte has constanly reassured the public of his promise to sustain the previous administration’s momentum for social development as well as to confront the challenges it failed to address by introducing radical changes. Although the first few months of his term was spent on making true his campaign promise on a war on drugs, Duterte, in his first State of the Nation Address in 2016 articulated the broad strokes of his administration’s social development agenda: to improve the people’s welfare in the areas of health, education, adequate food and housing, among others.

The 2017-2022 Philippine Development Plan (PDP) fleshed out Duterte’s pronouncements into actual strategies and programs the government intends to pursue in the next five years. Banking on people’s aspirations, it intends to establish a distinct national vision/framework for development, setting it above the inclusive growth model promoted by the last administration. Highlighting the human development approach, the PDP aims to implement government “policies, plans and programs anchored on the people’s collective vision” to uplift the living conditions of every individual, induce the expansion of the middle class and achieve a society “where no one is poor.”

The growth objectives presented in the PDP however are not entirely as people-centered as they appear. Similar to its predecessor, there are clear manifestations towards broadening private sector involvement, as well as facilitating connection to local and global value chains.1 While this is not entirely wrong in the economic/growth discourse, private investments particularly in the delivery of essential social services often lead to privatization and has not exactly worked for the poor in terms of accessibility. These contradictory goals put into question how Duterte intends to confront social development challenges. Will the public still see the radical changes he promised?

Distinct or Similar?

Development is not only measured through economic gains but also through improvements in well-being and living conditions2. Enhancing capabilites (or what a person can be or can do in life such as being healthy or owning a home), provide individuals better opportunities to transcend poverty3. The other view is that it is important to develop a person’s capability because it has economic value4 and interventions are seen as capital to fuel economic growth.

The AmBisyon 2040 is supposed to sum up the living aspirations of most Filipinos. Based on a survey conducted by the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) before crafting the PDP, four out of five Filipinos want a simple and comfortable life, which means enjoying a middle class lifestyle such as owning a house (and a car) and having enough savings to afford education, health and other leisures such as travelling for vacations abroad. Also, three out of eight priority agenda in the AmBisyon 2040 pertain to social development and the extension of government services5 for housing, education, and health to every individual. Thus, enhancing the potentials of Filipinos is at the very core of the PDP’s 10th chapter on “Human Capital Development” which also interprets human development not just a means to an end, i.e. for capitalist production, but as an end goal itself. But does this distinction signal a complete departure from the old strategies and thrusts for social services delivery?

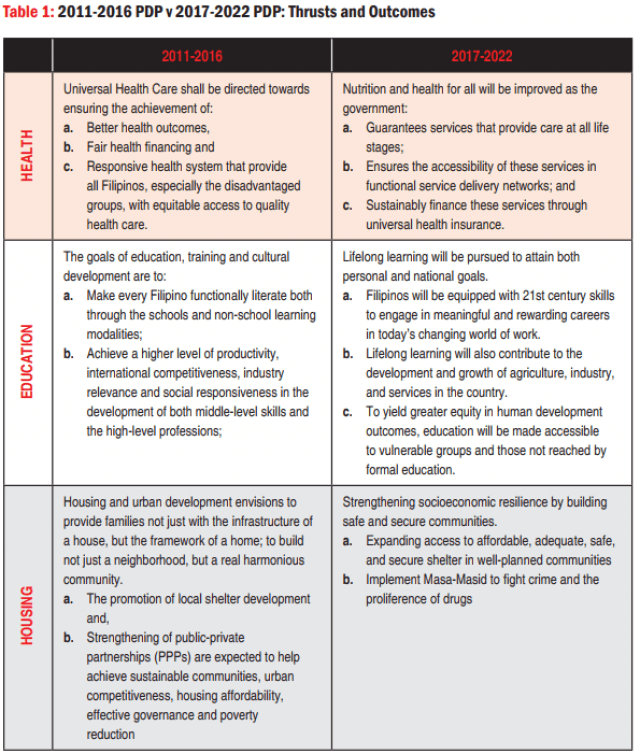

Financing, accessibility, and delivery networks are key factors in the delivery of public health service. Same with education which should also focus on access and relevance to industry growth. The housing sector also defined outcomes related to accessibility, but with the added feature of integrating the anti-drug campaign in communities. Based on NEDA’s assessment in the PDP, there are milestones in terms of achieving targets based on the indicators posted by the Millenium Development Goals, but several gaps in terms of accessibility and the quality of services delivered still have to be met. For health, the increase in the number of health facilities have resulted in the lack of health professionals deployed in communities and budget to sustain medical equipment and supplies. For education, net enrollment rates increased under the Aquino government, but the quality of education suffered due to imbalances in student-learner ratios as well as insufficient learning facilities. For housing, the direct housing assistance increased outputs, but were dampened due to the lack of social impact assessments, leaving thousands of houses in several resettlement areas unoccupied.6

Continuity is essential to progress. But does the need to address persistent social problems equate with the adoption of past development models? Looking closer at several key interventions in social development presented in the current PDP such as the expansion of service delivery networks and health financing, improvements in the quality of technical and higher education for global competitiveness and the increase of direct housing assistances, one could find resemblances in strategies and programs with those of the PNoy government’s. But the radical changes Duterte has promised in terms of health, education, and housing are somewhat missing, if we compare to the amount of rigor that went into framing other “priority” programs such as infrastructure and the war on drugs. While others may find fault there, 52 percent of Filipinos, according to a recent Social Weather Station survey7, still believe that Duterte will honor his pronouncements, such as the universal access to quality tertiary education or a universal ‘Cuban Style’ health care system. Based on these observations on the PDP, we can can take the view that the Duterte administration might not radically differ from past governments’ social development agenda. Whether or not government targets will be met or again missed depends on how bottlenecks in implementation as well as policy and budget gaps are addressed.

What the Budget Says

Having a vision is one thing, and providing the necessary budget towards realizing it is another. And from what the 2017 General Appropriations Act reveals, there is a gap between the promise of social development in the PDP and what we can expect. For education, a six percent8 automatic appropriation of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) is needed to realize the promise of free tertiary level education. Although both the Senate and the House of Representatives has passed the bill granting full tuition subsidy for students in state universities and colleges, the budget for operationalizing this has not been reflected in the 2017 budget. For public health services, an additional 57 billion is needed to bring the doctor to patient ratios9 near the Cuban Health System or even the World Health Organization standards, according to former appointee Health Secretary Paulyn Ubial10. For housing, Vice President and former Housing and Urban Development Coordinating Council Chief Leni Robredo said the “gold standard” target is two to five percent of the GDP in order to close the gap of 5.5 million housing units the previous administration left in socialized housing, or to build some 2,600 units per day.

Based on the 2017 GAA, what the government has allocated is a far cry from reaching the promises/ambitions of the Duterte government for health, education, and housing. The education budget is at 637 billion, with the Department of Education receiving the highest among all government agencies at 544 billion, registering a 32 percent growth increase from the previous year. The Commission on Higher Education budget also increased by 237 percent at 18 billion. But the total budget for public education is still only two percent of the GDP and is almost equal to the combined budget for the military and police, though lower than the budget for infrastructure development. In addition, both NEDA director general Ernesto Pernia and budget secretary Benjamin Diokno admitted that the government cannot afford the 100 million budget streamlined for the free college education bill11.

Although the health budget increased by 19 percent at 149 billion compared to the previous year’s, more than 50 billion was allocated to expand health financing under Philhealth. While the government aims to improve health access of the poor, the budget for service delivery networks was cut by 10 percent, and only 7 billion is alloted each for Health Human Resource Development and the Doctors to the Barrio Program, which would not meet the amount needed to close the doctor-patient ratio gaps.

The housing sector suffered deep budget cuts as well, down by 54 percent to 15 billion, which will be shared by the National Housing Authority, Social Housing Finance Corporation, and the National Home Mortgage Finance Corporation, and the Housing and Urban Development Coordinating Council which is now under the Office of the Cabinet Secretary. This is despite the huge housing backlog of 5.5 million units12, plus the 1.5 million target for direct housing assistance under the 2017 PDP.

While Duterte has set the bar high through these promises, how they will become reality is not very clear when the budget is used as indicator, even if only for this year. The 2017 budget’s priorities are: peace and security, infrastructure development, and the war on drugs.

Legislative Support

The legislative agenda presented for social reforms under the present PDP seems to lack the radical shifts towards attaining the promises pronounced by Duterte for health, education, and housing. Even notable policies such as the passage of the National Land Use Act, the Idle Land Tax Bill, the Philippine Qualifications Framework Bill, and the National Mental Health Care Delivery System have been inherited from past Congresses.

This does not mean, however, that the government will not pursue future policy reforms. But in terms of numbers, the government must have been either selective or realistic on what policies they want the PDP to endorse. Given that the PDP presents a space to put forward the policy foundations needed to reinforce government goals and ambitions, it only endorses 14 new policies for three sectors compared to the 13 policies endorsed only for infrastructure development. These policies also appear to be less exhaustive compared to those proposed under infrastructure development.

For education, priorities have transcended basic education to include improving the quality of mid-level to higher education, as highlighted by the Philippine Qualifications bill and Apprenticeship bill. For health, the government seems to lean towards population services, highlighted by the Local Population Development Act and the Prevention of Adolescent Pregnancy Act. It is also important to note that the only policy agenda endorsed by the plan for expanding health human resources are Amendments on the Barangay Nutrition Scholar program. For housing, the legislative agenda remains addressing the structural/systemic discord in housing services through the creation of the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Socialized Housing Development Finance Corporation, and the passage of the Comprehensive Shelter Finance Act—all of which have already been filed and refiled numerous times.

Creeping Privatization

In Aquino’s PDP and economic policies, we have witnessed the expansion of private sector collaboration through the promotion of Private-Public Partnership (PPP) agreements. The same could be expected in the current PDP assuming that it remains “cognizant of the private sector’s efficiency and innovativeness,” further stimulating private sector participation in improving the quality and sustainability of its projects.

For education, private sector involvement is apparent on “updating course programs and the alignment of domestic regulations for the ASEAN Qualifications Reference Framework (AQRF), as well as in scaling up technical and vocational training programs.” For health, private provider participation will be “harnessed and coordinated when planning Service Delivery Networks, implementing interventions, and securing supply-side investments.” For housing, key shelter agencies are prompted to involve private stakeholders in crafting the National Resettlement Plan and to secure additional financing from the private sector to attain the expanded targets for socialized housing services.

In the current PDP, too, there are clear linkages between the government’s strategy in enhancing the quality of education to be more responsive to industry needs and private sector involvement in developing curriculums in the name of pursuing “leading-edge, commercial-ready innovations.” The PDP also states that the government also devise performance measures, incentives, and rewards for universities who collaborate with industry partners. While the number of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) in the Philippines is 10 times more than in its neighboring countries, it falls short in producing innovators with a ranking of 74 out of 128 in the Global Innovations Index.13 According to the PDP itself, this is caused by the increasing number of commercialized HEIs that use curricula that are misaligned with the Commission on Higher Education’s standards and policies as well as privileging of business interests over quality considerations. On the other hand, with 4,486 private schools offering senior high school, compared to 220 non-DepEd public schools, private education subsidies have already reached P23 billion in 201714, to accommodate K to 12 spillovers. The Voucher Program however has been mired in controversy due to the lack of accountability15, especially from private institutions that receive subsidy.

Private hospitals greatly outnumber government hospitals, particularly those with higher service capabilities.16 This basis alone, interventions therefore, to reduce “out-of-pocket” sources which highlight the thrusts of the 2017-2022 Philippine Health Agenda can be seen as a profitable arrangement for corporations engaged in the health sector. In addition, the incumbent health secretary also declared that at least 33 of the 72 public hospitals will be privatized to gain financial autonomy17. This strategy would further deprive the poor of health care services since, in the name of financial viability, corporations will still require patients to pay on top of government subsidies. In 2016, the Philippine Institute for Development Studies observed lower health service utilization in areas where the private sector had increasing role. In that same year, the Commission on Audit found that the Health Facilities Enhancement Program had roughly 1.1 billion due to “idle and/or unutilized hospital buildings, facilities, and equipment, among others.” Given the strategy to tap private investments for improving service delivery networks outlined in the PDP, the HFEP is in danger of being a vehicle for privatization by entering into public-private partnerships to improve facilities and equipment.18

In 2012, the Subdivision and Housing Developers Association presented to the Board of Investors their 2012-2030 Philippine Housing Industry Roadmap with calculations of the economic impact of private business investments for socialized housing; with 2.3 jobs created for every million invested, and for every peso invested, a 3.32 value multiplier for local businesses as well as a .047 income multiplier and 3.90 pesos tax multiplier for each household. While this only expounds the rationale behind private investments on socialized housing, the Ibon Foundation has warned that private developers will continue to amass profits from socialized housing through guaranteed payments from the government and that these socialized housing units will remain unaffordable and unattainable for many despite government-private sector collaboration to lower amortization costs.

Whose Development?

Kayong mga Pilipino nakikinig sa akin ngayon. Magpa-hospital kayo, ako ang magbayad, tutal hindi man nila ako mademanda. [To all Filipinos listening to me now. Go to hospitals, I will pay for it. Anyway, they won’t be able to sue me.] – said President Duterte in his 2017 State of the Nation Address.

Duterte is ambitious in envisioning the delivery of a holistic social development package, responsive to the aspirations of every Filipino and founded on improving the living conditions of the poor. Fleshing out these ambitions, however, remains a challenge especially when the 2017-2022 PDP merely escalates the strategies and programs of the previous administration for social development.

Cruel World. Homeless children sleeping on the EDSA-Guevarra Pedestrian Overpass, Mandaluyong City, Philippines. 2017 February 24. Photo by Galileo de Guzman Castillo

The human development approach in the delivery of education, health, and housing services is a welcome change, along with the emphasis of increasing quality, accessibility, sustainability, and innovativeness. The litmus test for this is addressing budgetary and operational impediments, which the government plans to do through private sector involvement, which is nothing new, much less radical.

Human capital development, although government has explicitly defined it as improvement of individual capacities as an end in itself, will inevitably be more targetted based on the economic value an individual could possibly generate. Human as Capital, in sum, is wealth viewed not as an end in itself but as a means to more wealth, something which the PDP embodies as it factors in industry participation, private sector investments and collaboration, and competitiveness as part of intended interventions and outcomes. By deliberatelty continuing the same strategies and programs found in the previous PDP, public investments made by the government will always be weighed by the economic outcomes.

There are both gains and losses in engaging in PPP, but the government should veer away from inviting business interests and profiteering in key programs that uplift the dignities of its citizens. Instead, it should focus more on effective and responsive program implementation as well as the timely and proper allocation, disbursement, and utilization of public funds.

1 Based on the Foreword on the 2017 Investment Priorities Plan, the need for this is as part of a grand blueprint to “strenthen the resurgence of manufacturing”

2 According to Amartya Sen, an Indian economist behind the Capability Theory and the Human Development Index.

3 Where ‘poverty’ is seen as a deprivation in the capability to live a good life. “The Capability Approach” – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/capability-approach/

4 Referring to “human capital”, a term popularized Gary Becker, an economist from the University of Chicago. It is also a collection of traits that translates to the total capacity of the people that represents a form of wealth which can be directed to accomplish the economic goals of a state.

5 The other 5 pertains to Tourism, Manufacturing, Connectivity, Agriculture and Financial Services

6 i.e. the idle housing project in Pandi Bulacan that the Kalipunan ng Damayang Mahihirap (KADAMAY) occupied in March 2017.

7 Expected Fullfillment of the President’s Promises, 2017 Social Weather Report, Social Weather Stations: https://www.sws.org. ph/swsmain/artcldisppage/? artcsyscode=ART-20170512214448

8 According to Sanlakas, a party-list organization in the Philippines, advocating th SixWillFix campaign for the education sector. http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/857414/youth-groups-hit-duterte-on-false-promise-of-free-education

9 1 doctor to 20,000 population. The Philippines is currently at 1:33,000 according to the Department of Health.

10 Jee Geronimo, “Learning from Cuba’s health system: 35,000 more doctors needed in PH” http://www.rappler.com/nation/145333-ubial-cuba-health-system-doctors-needed

11 Lira Dalangin-Fernandez. Govt can’t afford free tuition – economic managers. http://www.interaksyon.com/govt-cant-afford-free-tuition-economic-managers/

12 Amor Canlang The continuing saga of socialized housing in the Philippines, http://www.businessmirror.com.ph/the-continuing-saga-of-socialized-housing-in-the-philippines/

13 Honly 81 researchers per million population compared to indonesia at 205

14 DepEd expands access to secondary education through GASTPE, http://deped.gov.ph/press-releases/deped-expands-access-secondary-education-through-gastpe

15 DepEd’s voucher program lacks transparency—solon, http://thestandard.com.ph/news/top-stories/238939/deped-s-voucher-program-lacks-transparency-solon.html

16 Based on 2015 DBP and DOH Bureau of Health Facilities and Services Data. Privately owned Tertiary level hospitals outnumber government

17 Dr. Eleanor Jara. Duterte’s first year: Philippine health agenda ‘a sham’. http://www.rappler.com/views/imho/175296-duterte-first-year-philippine-health-agenda

18 Health Facilities Enhancement Program (HFEP): Ubial DOH’s White Elephant, Health Alliance for Democracy, September 2016.

![[IN PHOTOS] In Defense of Human Rights and Dignity Movement (iDEFEND) Mobilization on the fourth State of the Nation Address (SONA) of Ferdinand Marcos, Jr.](https://focusweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/1-150x150.jpg)