by Clarissa Militante

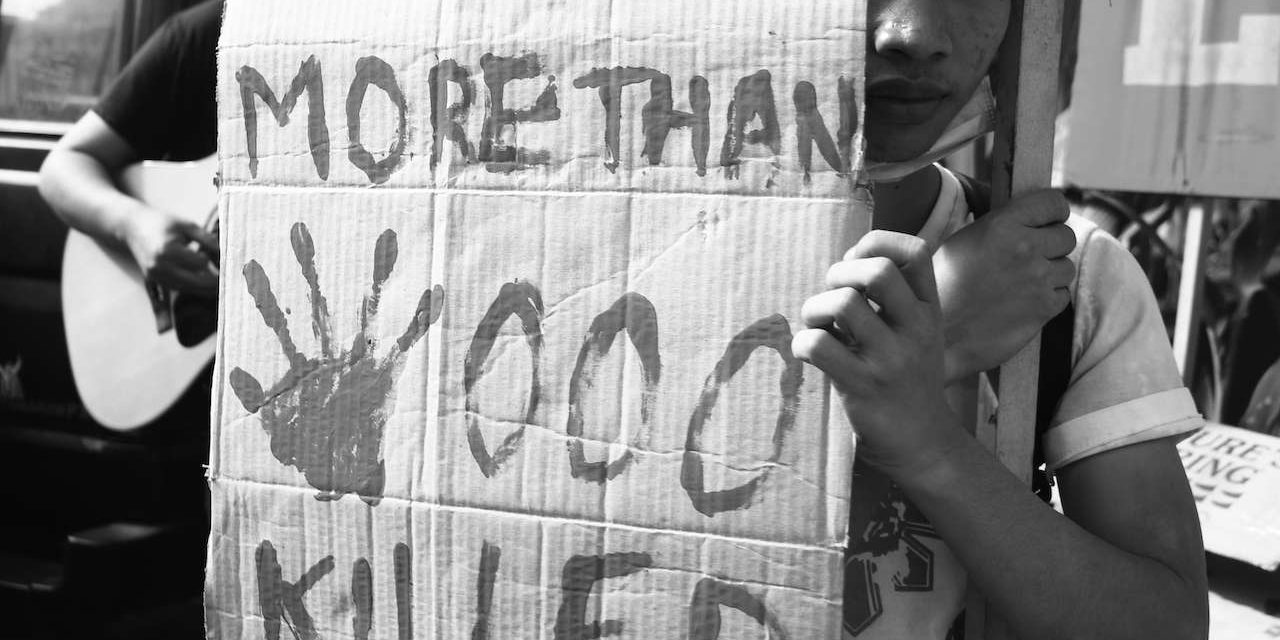

About the cover photo: Rodrigo Duterte’s flagship domestic policy, The War on Drugs, has killed thousands—and the death toll continues to rise. International Human Rights Day mobilization, Manila, Philippines. 2016 December 10. Photo by Galileo de Guzman Castillo

Where lies the coherence between pronouncement, policy, and execution in the Duterte government is in its war on drugs, via project double barrel or tokhang (local term for the war on drug campaign).

President Duterte won on a campaign platform that had for its central program a war on drugs aimed at addressing criminality with iron hand, and with drug addiction seen as the existential threat to the nation. This promise hit the ground running immediately after he was sworn into office. On the first year of execution, this violent, uncompromising approach has already resulted in the deaths of 7,000 to 10,000 people.[1] (Other claims say the figure is higher, but with the numbers from the police not very reliable, it’s hard to be conclusive; what is conclusive is that thousands have died as a result of this bloody policy, which the President has vowed to continue until the end of his term)

But the war on drugs is not just about peace and order, and security (maybe for select members of the population). It fits well in a social-economic agenda that has no place for the poor—our own “wretched of the earth”—and is underpinned by an economic system that kills off (literally and figuratively) those who could not survive the free market jungle. From news reports, the victims’ profile would tell us that they belonged mostly to the urban underclass, the slum dwellers, even if the number of those killed would vary even from official government sources.

It is a system, which according to Loïc Wacquant, privileges the middle class and the rich who can survive and provide for themselves, “rewards individual responsibility,” but punishes those who fall into the cracks. Below the cracks there are no more safety nets.

Wacquant, in his books Punishing the Poor—The Neoliberal Government of Social Insecurity and Ordering Insecurity Social Polarization and the Punitive Upsurge, underscores the link between the “ascendancy of neoliberalism” (1980s onwards) as political-economic project and the rise of the “punitive state”. In this social-political-economic order, there has been “rolling off of the welfare state, giving way to the privatization of the public.”[2]

What is happening in the Philippines is not without precedence, as Wacquant cites France (which has demonized the ‘refugees’) and the US, where the poor African-Americans are the evil and threat; it is also in the US where the term war on drugs originated. But to revise Wacquant a bit, in the Philippines now, the state is not only punishing but killing off the poor.[3]

The Targets: the Urban Underclass

Here’s the social-economic backdrop of the war on drugs.

The urban underclass has grown considerably and in such a fast pace in recent decades; this is both a result and cause of rapid urbanization in the Philippines. Another factor that has greatly contributed to this breakneck urbanization has been “the radical transformation of the city landscape in the mid-‘70s to the 2000s…(especially) in Metro Manila and its peripheries, namely the provinces of Cavite, Laguna, and Rizal to its south, and Bulacan to the north…” with Metro Manila reaching “a hundred percent level of urban land use in the ‘70s, and experiencing several construction booms in the periods 1993-1997, 2003-2008, and 2010-2013…”4[4]

This has spawned problems such as increase in urban poor population, poverty incidence and magnitude, more marked social division in urban areas between the haves and have-nots, as seen in the rise of commercial enclaves and fenced/secured residential areas while the roads and public facilities in the urban poor districts are undergoing decay, and worse they live in dilapidated shanties and on extra-legal status.

The Philippine Institute for Development and Studies projected that “without adequate intervention, Metro Manila’s slums will increase to 53.6 percent of its population, and one-third of all residents of large towns and cities (33.7 percent) will likely be slum dwellers.”[5]

In 2014, the magnitude of urban population in the Philippines was already 44,104, 820 (or around 44 percent of the population), making the country the sixth most urbanized in Southeast Asia in terms of the percentage of urban population.[6] Also in the same year, the magnitude of slum population registered at 17,055,400, which was about 38 percent of total urban population.[7]

Before this, the growth of slum population from years 2004 to 2006 was 3.4 percent annually, “which exceeded the population growth of urban and metropolitan areas of 2.3 percent….”[8] These slum dwellers were located in “more than 500 dispersed shantytown communities—particularly in Quezon City, Manila, Caloocan, Navotas, Las Piñas, Paranaque, Marikina, and Makati City.”[9]

This urban underclass comprised mostly of the so-called slum dwellers, characterized by their extra-legal status in places of residence, an inability to participate in the formal economy, with limited-to-no-access to resources needed for subsistence, and are “typically excluded from government registries and regulatory instruments. They are also marginalized in terms of basic services, such as education and health, potable water and sanitation, power and telecommunications, infrastructure, public security mechanisms, and so on.”[10]

It is in these urban poor districts where most police operations and vigilante killings have been taking place in the past year. It is this urban underclass that comprises the victims of the war on drugs.

As per the June 2017 report of the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, the top five regions in terms of deaths as a result of project double barrel until January 2017 were: 2,555 killed (police figures/from police operations) Metro Manila with 983; Central Luzon 484; CALABARZON 304, Central Visayas, 167, and Davao region, 89.

The data of those killed during police operations match the data of deaths under investigation (DUI) (3,952 of the total also as of January 2017) in terms of location, meaning that the highest would be from Metro Manila or NCR, followed by CALABARZON and then Central Luzon (with a little difference/variation from the ranking in those killed in police operations where Central Luzon came in second). In DUIs, Central Visayas and Davao placed number five, and Northern Mindanao figured in as number four.

Also very telling would be the number and location of “drug-affected barangays” as of April 2017. According to PCIJ, the terms ‘drug-affected’ was not clearly defined in government data. Did this mean they have the highest concentration of drug users; were they central areas in the drug trade; or location of identified drug dens; or had to do with the number of those killed? PCIJ also noted that a year after tokhang, which supposedly aimed to stem the growth of drug use and drug users, the number of barangays affected has increased, from 32 to 36 percent in July 2016 to 48 percent of the total barangays in the country by April 2017.

No Anti-Poverty Program

Despite its rhetoric, the government does not prioritize social safety nets for the poor. The Philippine budget for 2017, called the People’s Budget, mentions as one of four pillars social order and equitable progress. It is explained as: “To foster peace and progress, especially in conflict-affected areas, the 2017 Budget will fund programs and projects designed to fight crimes and instill order in society. It also reinforces infrastructure investments and expands employment opportunities to ensure that growth is felt in the lagging regions.”

It can be gleaned from the language how social order is no longer based on addressing the deeper causes of disorder, which is poverty, lack of education, lack of livelihood and resources for the poor to survive, to re-enter mainstream society as productive citizens and not remain as dregs of society.

In the 2017 budget, under the budget for social protection, the conditional cash transfer will get 78.69 billion and housing development, 14.41 billion. Other items we need to look at in the budget:

• For housing: housing development is assigned 119 billion, water supply 9.16 billion, community development, 1.55 billion;

• Public health services get 50.20 billion.

Meanwhile, public order and safety will get 170.80 billion, and under it, police services will have 115.07 billion while under Defense, the military defense gets 113.7 billion.

Under the previous government, the social service sector’s share increased annually from 2010 to 2016, from 31.1 percent (479.9 billion) to 36.6 percent in 2016 (952.7 billion); although 2015’s share was higher at 37.2 percent, in actual monetary terms it was 842.8 billion.

Urban Apartheid and Struggle for Space[11]

The social-economic divide in urban and urbanizing areas, specifically in Metro Manila and its peripheries to the south and north, is reflected in how space has been used and who has benefited. This is seen both in private-led real estate projects and government infrastructure development program.

Under the PNoy government, the urban development trajectory was towards what could be called “bypass urban implantism…(or) bypassing the congested arteries of the ‘public city’ and ‘implanting’ new spaces for capital accumulation that are designed for consumerism and export-oriented production.”[12]

One example of this kind of infrastructure project started by the PNoy government and is being continued and claimed as its own by the current administration is the skyway. It is now being expanded to link southern Luzon to the north and key parts of the Metro. One key link in this network of skyways are those that link different parts of Metro Manila and Cavite to the international airports; e.g. from the international airports to the hotels, casinos, and commercial enclaves on Macapagal Road. The Duterte government is not veering away from such projects of his predecessors, with majority of the planned infrastructure projects (40 percent) still concentrated in and benefitting Metro Manila and Luzon. (See Stories Behind the Numbers: Dissecting Duterte’s Build, Build, Build Program on page 9).

Essentially, it is the kind of infrastructure program that heightens the spatial divide; that develops select areas of the city according to international standards while “bypassing the rest of Metro Manila’s woes and its poorer inhabitants.”[13] This spatial divide has created apartheid among the middle class directed at the poor. Currently, the war on drugs has exacerbated this apartheid as the poor has been painted as source of insecurity, and from whom the rich and middle class have to be protected.

A recent Pulse Asia survey showed that “82 percent of Metro Manila residents feel safer” as a result of the war on drugs.[14] Predictably, Philippine National Police Director General Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa has also claimed that the reduction in the crime rate in the past year from mid-2016, when Duterte assumed presidency, to the first half of 2017 has been due to project double barrel. However, PNP data also show that crime rates have actually been declining, although not steadily in the period 2014-2015; by 16 percent from 2013 to 2015 and five percent from 2014 to 2015. The PNoy government’s own claim was this was due to its Oplan Lambat-Sibat, which intensified surprise checkpoints, raids and home visits directed at gun owners, and intelligence gathering.[15]

Apartheid has gained a new face owing to the stigma that has now been attached to being drug users or just being suspected or accused of being one.

Weakening the Poor’s Agency[16]

How do the poor fight back now? What agency is left to them?

“The members of our community used to stand together and fight side-by-side against demolition. We were ready to die fighting for our rights, but now there’s so much fear in the community because many have been killed because of the war on drugs,” said a woman community organizer in Caloocan, northern Metro Manila, in one of the city’s districts populated by informal settlers. She requested anonymity during a focused group discussion conducted by In Defense of Human Rights and Dignity Movement (iDEFEND), a coalition of human rights defenders formed in August 2016.[17]

Why were they not afraid to die fighting for their rights before, but now could not even organize the members to stand up against illegal arrests and killings?

“There’s so much distrust now. I am distrusted, because one of my relatives was killed and branded a drug addict,” the woman community organizer said.

It is the stigma, said the other community leaders, who all requested anonymity for fear of reprisal, as their community continues to be an open target for the war on drugs. Fighting for their right to a decent place of living was easier for these organizers than now defending the right to life and due process of drug addicts and pushers who are perceived as mere criminals.

Community kinship has also been a casualty.

“If you were killed because of tokhang (local term for the war on drug campaign), nobody even goes to your funeral, except your own family,” said one of the discussants.

“That is if you are able to claim your dead bodies from the morgue. Most of us hardly have the money to pay the morgue. And I’ve tried to approach the local government for support but when they learn that your relative died because of tokhang, then they refuse to give support,” shared another woman leader.

They admitted that there were users in their neighborhood, even pushers—small-time pushers, they said. They knew these neighbors: young boys who would sniff solvent because this was cheaper (at 10) than buying food and it would make them numb to hunger for three days; the neighborhood basurero (people who earn from finding saleable stuff from garbage) who used shabu (a slang term for the drug methamphetamine) to stay awake in the wee hours of the morning when they needed to be awake because of their jobs; young men who were runners for the big-time pushers so they could earn pittance from selling tingi or drugs in small amounts. They were aware that using and selling drugs were not right, but it was part of their daily living in a poor neighborhood.

Their stories should not aim to romanticize but humanize the narrative of those who are being felled like pins in a bowling game; to show that the drug menace has social-economic roots.

“Sana po mawala ang stigma. Sana pa maalis iyong paghihinalaan ka at di na pagtitiwalaan ng mga kapitbahay mo. Marami po sa amin umaalis na lang sa komunidad.” (I hope the stigma will disappear. That there would no longer be mistrust among neighbors. Many are choosing to leave the community).

——–

1 The police claim that there have only been a little over 3,000 that could be directly linked to police operations; DUI not included; but human rights organizations say there are more

2 Wacquant

3 Wacquant

4 Bello, Walden; Cardenas, Kenneth; Cruz, Patrick Jerome; Manahan, Mary Ann; Militante, Clarissa; Purugganan, Joseph; Chavez, Jenina Joy. State of Fragmentation: The Philippines in Transition. Focus on the Global South & Friedrich Ebert Stiftung; Quezon City, 2014

5 Bello, Walden; Cardenas, Kenneth; Cruz, Patrick Jerome; Manahan, Mary Ann; Militante, Clarissa; Purugganan, Joseph; Chavez, Jenina Joy. State of Fragmentation The Philippines in Transition. Focus on the Global South & Friedrich Ebert Stiftung; Quezon City, 2014

6 https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/philippines/urban-population

7 https://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/SeriesDetail.aspx?srid=711&crid=

8 Bello, Walden; Cardenas, Kenneth; Cruz, Patrick Jerome; Manahan, Mary Ann; Militante, Clarissa; Purugganan, Joseph; Chavez, Jenina Joy. State of Fragmentation The Philippines in Transition. Focus on the Global South & Friedrich Ebert Stiftung; Quezon City, 2014

9 Bello, Walden; Cardenas, Kenneth; Cruz, Patrick Jerome; Manahan, Mary Ann; Militante, Clarissa; Purugganan, Joseph; Chavez, Jenina Joy. State of Fragmentation The Philippines in Transition. Focus on the Global South & Friedrich Ebert Stiftung; Quezon City, 2014

10 Bello, Walden; Cardenas, Kenneth; Cruz, Patrick Jerome; Manahan, Mary Ann; Militante, Clarissa; Purugganan, Joseph; Chavez, Jenina Joy. p. 202; Chapter 6: State of Fragmentation The Philippines in Transition. Focus on the Global South & Friedrich Ebert Stiftung; Quezon City, 2014

11 Bello, Walden; Cardenas, Kenneth; Cruz, Patrick Jerome; Manahan, Mary Ann; Militante, Clarissa; Purugganan, Joseph; Chavez, Jenina Joy. p. 202; Chapter 6: State of Fragmentation The Philippines in Transition. Focus on the Global South & Friedrich Ebert Stiftung; Quezon City, 2014

12 Bello, Walden; Cardenas, Kenneth; Cruz, Patrick Jerome; Manahan, Mary Ann; Militante, Clarissa; Purugganan, Joseph; Chavez, Jenina Joy. p. 202; Chapter 6: State of Fragmentation The Philippines in Transition. Focus on the Global South & Friedrich Ebert Stiftung; Quezon City, 2014

13 Bello, Walden; Cardenas, Kenneth; Cruz, Patrick Jerome; Manahan, Mary Ann; Militante, Clarissa; Purugganan, Joseph; Chavez, Jenina Joy. p. 202; Chapter 6: State of Fragmentation The Philippines in Transition. Focus on the Global South & Friedrich Ebert Stiftung; Quezon City, 2014

14 http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/884205/pnp-murder-homicide-other-crimes-decreased-under-duterte-admin

15 http://news.abs-cbn.com/news/02/13/17/philippines-crime-rate-falls-13-percent-in-2016

16 This section was originally published by ucanews

17 Focus Group Discussion; September 2016