by Mary Ann Manahan

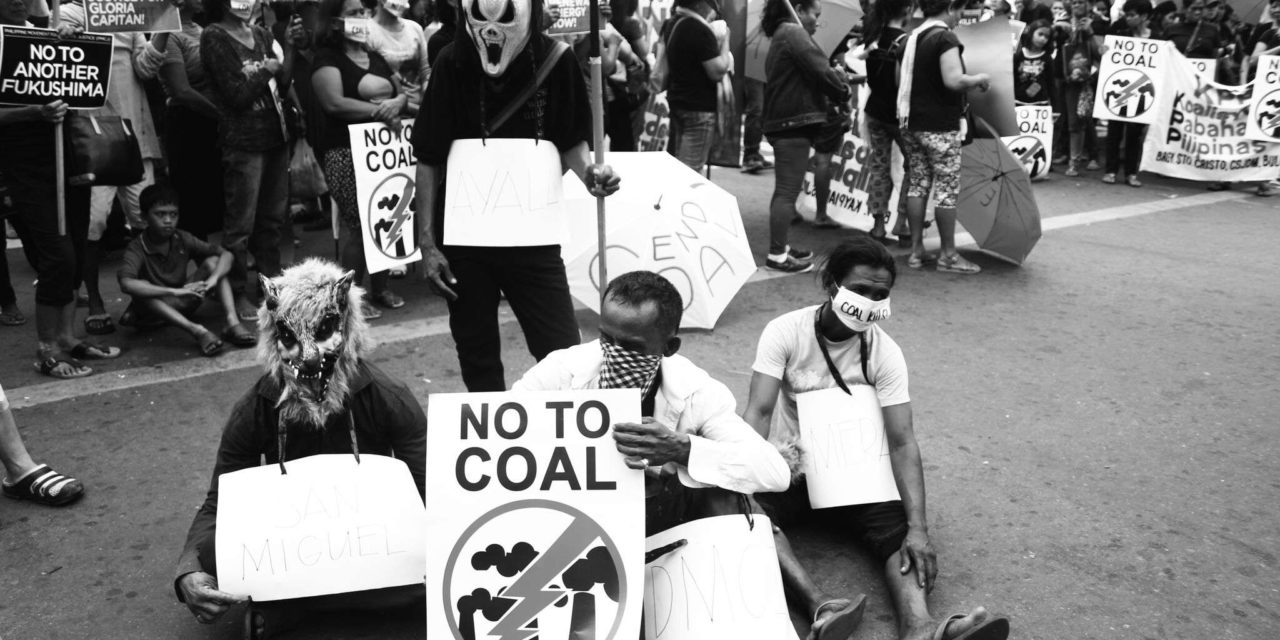

A day after President Duterte was sworn into office in June 2016, Gloria Capitan was shot pointblank by two unidentified assassins riding a motorcycle at her karaoke bar in Mariveles, Bataan. Capitan was a staunch environmentalist and human rights defender who had led the fight against the open coal stockpile operating in her village and other coal-fired power plants in the province of Bataan.[1] Duterte had no direct role in the murder of Capitan but her death seemed to be ominous of what’s coming for the country’s environment and its defenders.

Fragile Frontiers in Crises

The Duterte administration inherited an economy with high growth rates, which earned the country a status of ‘darling of Southeast Asia’.[2] However, despite this status, the Philippines still suffers from structural problems such as jobless growth, high inequality and persistent poverty, and deepening ecological crisis, which have long-lasting impacts on the country’s development path, and peoples’ survival. The country faces severe environmental vulnerabilities even as “in the 1990s the plunder of resources… (was) at a rate that is fastest in the world… (so that) there are a few places you can go in the Philippines without meeting some sort of ecological disaster.”[3] The Philippines relies on many interlinked and vital ecological resources such as forests and watersheds, which continue to be exploited and plundered by big and extractivist businesses such as illegal logging, mining, and coal-fired power plants.[4] It is estimated that one-seventh of the mining and exploration concessions have contributed to watershed stress and at least 10 mining operations were involved in 15 cases of water pollution and environmental degradation in the past decade.[5]

The country has lost 50 percent of its forests in the last one hundred years despite efforts to rehabilitate and reforest, making it one of the top 10 deforested countries in the world.[6] As forest and upland resources directly support about 30 percent of the population, mainly indigenous and farming communities comprising the poorest sectors, the disappearance of our forests has affected the lives of more than 100 diverse Philippine ethnic communities and the survival of more than two million plant species, landing the country on the top 25 global biodiversity hotspots.[7] Forest disappearance has led to disastrous consequences such as flashfloods, which have claimed thousands of lives, destroyed livelihoods, and displaced hundreds of thousands more from their home. The country’s overall environmental vulnerability has also increased due to the perilous effects of extreme weather events and severe climatic anomalies that have become the new normal, exacerbating existing inequalities and poverty situations.

The Duterte administration is therefore confronted with the sustainability imperative, i.e. improving people’s lives while respecting the ecological limits and carrying capacity of the country. Has he set the direction for a sustainable development agenda?

Duterte’s Green Agenda

Described as an anti-mining advocate by his constituency during his tenure as mayor of Davao City, President Duterte has banned all mining operations within the city’s perimeter. Throughout his campaign, he also expressed support for ‘responsible mining’ before members of the Wallace Business Forum in February 2016, arguing that mining operations should be allowed to continue as long as they uphold the most stringent environmental standards. After taking on the presidency, he sent a stronger signal to the mining industry by promising to halt the operations of big mining companies destroying the environment and to use the military in dealing with irksome mining firms disobeying environmental laws. As an ultimatum, he warned that “if you cannot do it right, then get out of mining.”[8]

During his first State of the Nation Address, he vowed to implement a number of environmental reforms during his first 100 days, which included a mining audit of all operations and a moratorium on new mining projects, intensification of the campaign against illegal logging, dismantling of illegal fish pens in Laguna Lake, a review of the country’s energy plan, and a moratorium on coal-fired power plants, while making a just transition to renewable energy and ensuring affordable electricity cost. Other items on his environmental agenda are final closure and rehabilitation of the Carmona Sanitary Landfill, and use of waste-to-energy technology to resolve the garbage problem of Metro Manila and other cities. These reform measures were already components of Duterte’s green agenda during his campaign. According to Jaybee Garganera, national coordinator of the Alyansa Tigil Mina (ATM) and member of Green Thumb Coalition (GTC), one of the broadest environmental coalitions in the country, “as far as our coalition is concerned, candidate Duterte promised about 60 reform measures in the nine areas that we work on, namely biodiversity and ecosystem integrity; natural resource and land use management and governance; human rights and integrity of creation; climate justice; mining, extractives and mineral resource management; energy transformation and democracy; sustainable food sovereignty; people-centered sustainable development; and waste. These form the green scorecard, which we are basing on our assessment of his one year in power.”[9]

The Philippine Development Plan (PDP) 2017-2022 also reflects the reforms that are the “foundations for sustainable development: the physical environment will be characterized by a balanced and strategic development of infrastructure, while ensuring ecological integrity and a clean and healthy environment”.10 While the current PDP does not define ecological integrity, the plan talks about sustained biodiversity and functioning of ecosystem services (e.g. forest cover, coastal and marine habitats), improved environmental quality (air, soil fertility, land, solid waste and water), increased adaptive capacity and resilience of ecosystems, and improved socio-economic conditions of resource-based communities (e.g. employment from ecotourism and sustainable community resource-based enterprises). The mid-term plan contains the following key components:

• shift to renewable energy,

• use of waste-to-energy technology,

• mainstream disaster risk and rehabilitation management (DRRM) and climate change adaptation (CCA) into local development plans,

• uphold the Mining Act of 1995

• climate proofing of infrastructure and housing projects to build safe and secure communities,

• pay attention to specific vulnerability of women, peoples with disabilities, indigenous peoples in disasters and evacuation centers, and

• diversify livelihood for resource-based communities.

The green agenda looks solid on paper and through his initial pronouncements about environmental issues, plus the appointment of Regina ‘Gina’ Lopez, a staunch environmentalist and anti-mining advocate, to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), it appears that Duterte’s strongman leadership will finally benefit the environmental front. (Ms. Lopez was not approved by the Commission on Appointments; civil society organizations had expected the President to defend her and sway his majority in Congress to confirm her)

Inherent Contradictions

However, less than a year into his office, contradictions have become apparent. There are several manifestations of these inherent contradictions. First, Duterte’s PDP treats ecological integrity as crucial for economic growth, which means that conservation is vitally important for capitalist expansion or to achieve an upper middle-class society based on AmBisyon 2040 (see Dutertenomics: Recipe for Inclusive Development or Deeper Inequality? on page 3). Policies that will accelerate infrastructure development (see Stories Behind the Numbers: Dissecting Duterte’s Build, Build, Build Program on page 9), energy, and reforestation through the continuation and enhancement of the National Greening Program (NGP) are concrete examples of this ‘balancing act’ between preservation/conservation and exploitation.

While a shift to renewables is supposed to be a focus of the government’s energy policy (adopting Arroyo/Aquino’s PDP), President Duterte has also committed to coal production and use. Renewable energy use, which started in 2009, accounted for 39 percent of the country’s energy share, but in 2016, its share decreased to 29 percent and may continue to decline in the next five years.[11] On September 2016, the President publicly announced that “if we want to industrialize our country because we were left behind by so many generations, you have to keep up with developments and… right now is to use coal, cheap, it’s available although it is maybe deleterious to the whole of the climate of planet Earth.”[12] Despite appeals from renewable energy advocates, President Duterte repeated his pronouncement, during the groundbreaking of a 0.6-megawatt Pulanai hydroelectric power plant in Bukidnon on December 2016, that coal would remain to be the most viable source of energy for the country to industrialize.[13]

Another disconcerting pronouncement was that “$1 billion is earmarked for the power plant’s rehabilitation and will either be undertaken by a government-to-government arrangement or by private corporation selected through “a transparent bidding process.”[14] Nuclear energy has been widely acknowledged to be detrimental to a country’s development path, environment, and people’s survival.

Environmental groups have expressed concern that the country’s dependence on fossil fuels and coal could skyrocket to as much as 70-80 percent by 2030.[15] On June 2017, the Philippine Movement for Climate Justice[16], Center for Energy, Ecology, and Development (CEED), and De La Salle University College of Law filed a 64-page petition for writ of continuing mandamus with temporary environmental protection before the Supreme Court, calling for the high court to order the Department of Energy and DENR to strictly regulate the operation of coal-fired power plants and reduce the country’s dependence on fossil fuels.

Meanwhile, the current administration’s policy on forest and upland resources hinges on the multi-billion NGP. The NGP has been mired in controversies of public misuse of funds and corruption, and has been accused of perpetuating a mindset of ‘reforesting with harvestable trees’ or ‘plant trees in order to harvest it’. The Commission on Audit in 2013 called the NGP as a failed program. It, therefore, begs to be asked why President Duterte has committed to a very expensive program which in the past have had questionable outcomes.

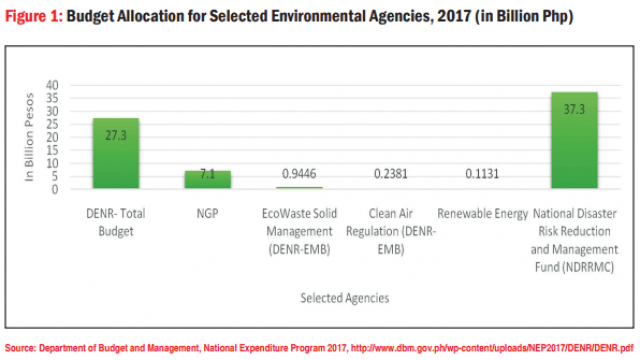

Also, the 2017 budget, which reflects government priorities and plans, shows that the DENR has the 9th largest budget allocation at 27.3 billion, increasing by 5 billion from 2016. Figure 1 illustrates that the NGP comprises 26 percent of DENR’s budget, which aims to reforest 183,552 hectares of land and produce 171 million seedlings. Apart from the DENR, DRRM gets a bigger piece of the pie, with 37.3 billion, which includes an allocation of 10 billion from the Calamity Fund and the People’s Survival Fund worth 1 billion. Ecowaste and solid management is receiving 944.6 million, while clean air regulation gets 238.1 million; for renewable energy, 113.1 million. The budget for renewables, i.e. for the National Renewable Energy Program and the National Biofuels Program, is one of the lowest budget allocations for environmental agencies in 2017.

‘Bigay-bawi’ and a Captured Mining Agenda

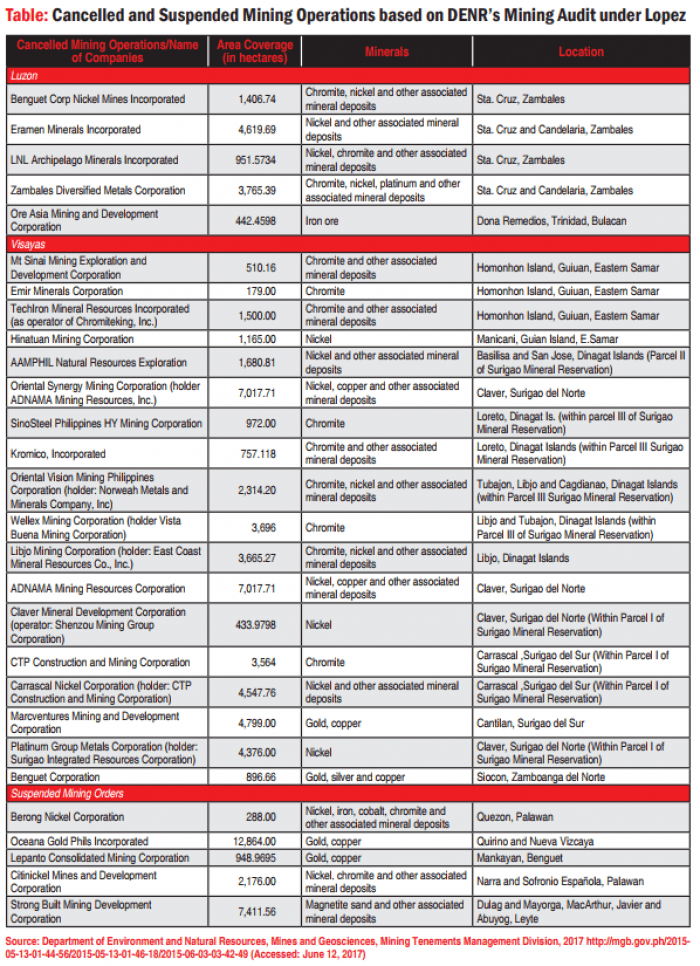

The biggest controversy in the first year of Duterte is his policy on mining. With former Secretary Gina Lopez at the helm of DENR at the beginning of his term, she was quick to issue Memorandum Order No. 2016-01, which called for a mining audit of all operations and a moratorium on the approval of new mining projects. The former secretary had ordered the closure of 23 mining operations, suspension of five contracts, and cancellation of 75 mineral production sharing agreements, all covering close to 84,000 hectares of lands in Eastern Samar, Dinagat Islands, Surigao del Norte, Surigao del Sur, Zambales, Zamboanga del Norte, Palawan, Benguet, Quirino, Nueva Vizcaya, Bulacan, and Leyte, which represented 70 percent of the total operating metallic mines in the country (see Table).[17] And the mines affected belonged to the Alcantara, Borja, Pichay, Zamora, Leviste, and Gatchialian families, to name a few, which also comprise the country’s political and economic elites.

According to Garganera of ATM, the mining audit has uncovered various violations of environmental standards and laws, unsystematic mining methods, and negative impacts to affected communities’ right to livelihood, a safe and healthy environment, and freedom of expression.[18] Other institutional reforms are administrative orders that tackle the formulation of a freedom of information (FOI) manual, mandating mining contracts to participate in the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative, a multi-stakeholder platform that tackles good governance of oil, gas and mineral resources, and banning of open pit mining method for copper, gold, silver, and other complex ores in the country.[19] These are significant, progressive strides not only in as far as strong regulation is concerned but as well as in protecting the indigenous cultural and rural communities that are hosts to majority of the country’s mining operations.

However, Duterte’s economic managers led by Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III, who has business interests in mining (see Dutertenomics: Recipe for Inclusive Development or Deeper Inequality? on page 3), was critical of Gina Lopez’s reforms, arguing that mine closures were bad for the economy (with an estimated 653 million in foregone revenues) and jobs (allegedly affecting 1.2 million people), and that government can be sued by affected mining companies in international arbitration courts. Instead of the DENR issuance, Sec. Dominguez proposed that the Mining Industry Coordinating Council conduct a multi-stakeholder review on existing mining operations. The corporate backlash was in full gear, with mining companies reportedly banding together to block Lopez’s confirmation as environment chief. President Duterte confirmed this when he stated at a gathering of doctors in Davao City, that “sayang si Gina (It’s too bad about Gina). I really like her passion… But you know how it is. This is democracy, and lobby money talks.”[20]

The fate of the mine closures and suspensions remain unclear, with no timeframe and process governing the pending appeals at the Office of the President, and the issuance of the ore transfer permit which allows mining companies unhampered operations.[21] Lopez was soon replaced by Roy Cimatu, a former general of the Philippine Armed Forces, well known for his tainted human rights record as a military chief in Mindanao and with no environmental governance record. Cimatu was said to have been appointed by the President for his ability to “balance the concerns of environmentalists and mining groups.”[22] In a meeting with the European Chamber of Commerce of the Philippines (ECCP) in Makati City on June 2017, Cimatu said that his agency will continue to “strictly enforce mining and environmental regulations” and uphold the Mining Act of 1995. In short, a reversal of the decisions of Lopez and back to business-as-usual policy in favor of mining firms.

Disciplining Dissent

Since 2013, the Philippines has been considered one of the deadliest countries for environmentalists and human rights defenders in Asia. According to the recent Global Witness Report, 28 environmental-related killing were recorded in 2016, one-third were activists campaigning against mining and extractives, and half involved indigenous peoples as victims. Community leaders and civil society organizations are also concerned over the impunity in killings. For instance, Kalikasan-PNE, a network of environmentalists, NGOs and peoples’ organizations, recorded 17 extra judicial killings of environmental defenders under Duterte, 41 percent of the recorded cases involve state armed forces and 65 percent perpetrated in the island of Mindanao, where hotspots for struggles against extractives and mining are located.[23] Similarly, the GTC and ATM reported that the murder of several indigenous leaders in Mindanao remain unresolved and the island-wide declaration of Martial Law is a real threat to freedom of movement and rights to assemble of individuals, CSOs, and communities protesting against extractives and dirty energy.[24] With the government’s unwavering support for mining and extractives such as coal and the extension of Martial Law for another six months, it would not be a surprise if the country remains a dangerous place for environmental and human rights defenders in the next five years.

The control over forests and ecological resources will continue to be a fight between the have and have not. In the first year of Duterte, it is clear who won the political contest over how the environment will be governed and whose interests will prevail. Dissent against big, dirty money are disciplined either through violence or political maneuverings. For Gerry Arances of CEED, the implications are clear: “the gloves are off and it’s ‘back-to-the-trenches for the green movements’”.[25] Beyond personalities, however, the very governance framework that values the environment and ecological resources as ‘cogs in the growth machine’ already clarifies where the government’s priorities and actions lie.

*(Can be translated as ‘forward step followed by a backward step)

1 Cabe, D. (2017). “For Ate Gloria Capitan, a comrade in struggle” http://world.350.org/philippines/for-ate-gloria-a-comrade-in-the-struggle/ (Accessed: July 15, 2017)

2 Lim, J. A. (2015) “An Evaluation of the Economic Performance of the Administration of Benigno S. Aquino III”, Conference paper, AER, Pasig City.

3 Bello, W. Cardenas, K., Cruz, J., Fabros, A., Manahan, M., Militante, C., Purugganan, J. and Chavez, J. (2014) State of Fragmentation: The Philippines in Transition, Quezon City, Focus on the Global South and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid., p. 161.

6 Manahan, M.A. (2016) “Painting the Town REDD-Plus: Competing Narratives on Forest Tenure, Land Rights, and REDD+ within Contentious Politics in the Philippines”, unpublished master’s dissertation, University of Antwerp.

7 Guiang, E. S. and Castillo, G. (2005) “Trends in forest ownership, forest resources tenure and institutional arrangements in the Philippines: Are they contributing to better forest management and poverty reduction?”, Case study, FAO, Bangkok.

8 Jiao, C. (2016) “Mining has place in Duterte economic agenda – MVP”, CNN Philippines http://cnnphilippines.com/business/2016/06/22/manny-pangilinan-rodrigo-duterte-gina-lopez-mining-economic-agenda.html (Accessed on July 15, 2017)

9 Interview with Jaybee Garganera, June 22, 2017, Quezon City.

10 National Economic Development Authority (2017) Philippine Development Plan 2017-2022, NEDA, Ortigas Center.

11 Interview with Gerry Arances, July 6, 2017, Quezon City.

12 Philippine Information Agency (2016) “Climate group lauds Duterte’s openness to clean energy”,

http://news.pia.gov.ph/article/view/1461474590763/climate-group-lauds-duterte-s-openness-to-clean-energy#sthash.ToRFA97z.dpuf (Accessed: June 20, 2017).

13 Jerusalem, J. (2016) “Duterte: Green energy is good but we need coal” SunStar Cagayan de Oro, http://www.sunstar.com.ph/cagayan-de-oro/local-news/2016/12/10/duterte-green-energy-good

(Accessed: June 20, 2017).

14 Lucas, D. (2016) “Duterte gives nuke plant green light”, Philippine Daily Inquirer, http://technology.inquirer.net/55523/duterte-gives-nuke-plant-green-light (Accessed: June 19, 2017).

15 Interview with Gerry Arances, July 6, 2017.

16 PMCJ is one of the broadest coalition of climate justice activists and grassroots organization in the country, with members from Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao.

17 The area covered by the mining suspension and cancellation represent 11.17 percent of the total 751,636.077 hectares mineralized lands under different permits and agreements with the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (as of Feb 2017).

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid., slide 9.

20 Ranada, P. (2017) “Duterte on CA votes vs Gina Lopez: ‘Lobby money talks’”, Rappler, http://www.rappler.com/nation/168889-duterte-gina-lopez-lobby-money (Accessed: July 29, 2017).

21 GTC Mining Cluster, “Assessment of the First Year of Duterte Administration”, unpublished position paper, presented at the roundtable discussion on June 8, 2017, Quezon City.

22 Placido, D. (2017) “Palace: Duterte both pro-environment and pro-responsible mining”, ABS-CBN News. http://news.abs-cbn.com/news/05/10/17/palace-duterte-both-pro-environment-and-pro-responsible-mining (Accessed June 19, 2017)

23 Geronimo, J. (2017) “PH still deadliest country for environmental defenders-Report”, Rappler, http://www.rappler.com/science-nature/environment/175516-philippines-still-deadliest-country-asia-environmental-defenders-2016 (Accessed July 13, 2017)

24 Interview with Jaybee Garganera, June 22, 2017, Quezon City. Also see GTC Mining Cluster, “Assessment of the First Year of Duterte Administration”, unpublished position paper, presented at the roundtable discussion on June 8, 2017, Quezon City.

25 Interview with Gerry Arances, July 6, 2017, Quezon City.