By Ben Moxham(*) 18th November 2004

Today, the Australian Federal Senate will most likely rubber stamp a few obscure amendments to the Customs Act to activate the recently negotiated Thai-Australia Free Trade Agreement (TAFTA). While debate on the TAFTA in Australia barely spread beyond a few offices in Canberra, Thai farmers and workers took to the streets in protest at a trade deal that sells them out.

Bangkok is a sprawling mess of development. The view from this ninth floor balcony is hemmed in by skyscrapers and the droning expressways. Slums take shelter underneath the overpasses: their residents sweating over som tam stalls. A scattering of temples are outnumbered by the brothels – all blinking lights and car parks full of Mercs.

Here, social divisions can seem literally vertical – mapped out onto a city – as a nascent middle class ride atop healthy GDP figures while the rural poor, uprooted by their non-economic viability, live in the hidden niches of this pungent metropolis.

These twin processes of growth and alienation will be given a boost by the recently signed trade deal between Australia and Thailand. In Thailand, the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) debates were heated. Farmers and critics claim that Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra’s government sold out small farmers to their own big business interests. They took to the streets in protest while Thaksin lambasted them and obscured negotiation details. In Australia, the debate barely spread beyond a few offices in Canberra. Yet, the Australian Senate’s expected rubber stamp on the agreement today, will send ripples through Thailand.

THE (NOT SO) FINE PRINT

The Thai-Australia Free Trade Agreement (TAFTA) was concluded in the middle of this year and will come into effect at the start of next year. Then, more than half of Thailand’s 5,000 tariffs will be eliminated on products such as instant food, cars and jewelry. The remaining tariffs will be eliminated by 2010 on products such as canned tuna, textiles, footwear, auto-parts, steel, chemical products and plastics with some ‘sensitive’ products to be phased out by 2015 and 2020. on the Australian side, 83 per cent of tariffs will be cut to zero next year, with the remaining categories to be cut by 2015.

While Australian consumers might get 10 cents off their imported Durians and Rambutans, Thai farmers will be directly competing with Australia’s agribusiness juggernaut. They’re panicked. To allay their concerns, the TAFTA provides a longer phasing out period for directly competing products like beef and pork. In the most contentious area, milk and dairy products will eventually be able to enter Thailand tariff free by 2020.

Adul Vangtal, the President of Thai Holstein Friesian Association, is an outspoken critic of the TAFTA. He explains that milk has never been widely consumed in Thailand. Instead, the dairy industry was born through an act of Royal social and dietary engineering 40 years ago. King Bhumipol Adulyadej, an ardent promoter of rural development, saw it both as an opportunity to create employment in struggling rural communities and introduce a serious dose of calcium into the diets of Thai youth.

It has been reasonably successful: “The farmers in Ratchaburi province where I am from used to be sugarcane farmers but they were badly in debt,” explains Adul. “The Government started this project with the King to assist these indebted farmers. Now farmers have enough cash income to buy a bicycle or a motorbike and to send their kids to school.”

According to Adul about 40,000 families work in the dairy industry, organised into 117 cooperatives. This “social farming” as Adul calls it, is the lifeline that binds communities together. It’s a pattern all over Thailand where 60 per cent of Thais depend on agriculture and a third of these are small scale farmers.

COMPETE HOW, THAI COW?

This is in stark contrast to the way the cow business is done in Australia. According to Dairy Australia, Australia had 10,654 registered farms in the 2002/2003 financial year holding about 200 cows each. While in Thailand, “99 per cent of farmers are small with only 10 to 20 head of cattle each,” says Adul. Given the economic strength of the larger Australian farms, the more favourable climate and higher technology, Australia can produce milk for about two thirds of the cost of Thai farmers.

Research commissioned by the Thai government predicts that under the FTA, dairy imports will increase by 30% and the domestic price will drop by 30%. With these prices, “all the social farms will dissolve and farmers will lose their jobs,” says Adul bleakly.

The Thai government dismisses such pessimism, arguing that dairy tariffs will be slowly phased out, giving farmers enough time to adjust. “Adjust to what? Adjust to our lost jobs?” says an exasperated Adul.

Fundamental differences in land and climate make talk of adjustment meaningless. “Even EU and US farmers can’t compete with Australia and they are far more developed with higher production techniques than Thailand,” points out Jacques-Chai Chomthongdi, a trade campaigner with the activist research NGO Focus on the Global South. “In negotiations for the Australia-US FTA, the US didn’t even commit to a timeframe for liberalisation.” For Thailand, “We’d have to invade Cambodia and Laos to get enough land to compete with the Australians,” jokes Jacques-Chai.

The Thai government also counters that if producers are hurt by imports, it still has the right to implement safeguard measures. Adul strongly doubts their will, given their failure to assist farmers in tackling the industry’s existing problems. Even without the increased imports that lowered tariff barriers would bring, competition is already hurting farmers. “Our raw milk already has to compete with imports of powdered milk,” explains Cherdchai, a farmer from Udon Thani province. “Each year, when the imported products come, the price of our milk drops and we are forced to throw it away.” While the production grows by 10 per cent a year, consumer demand is only growing at 5 per cent. “So we already have an oversupply problem here,” adds Adul.

Australia has promised not to compete in the fresh milk market in Thailand. It’s hardly a generous offer considering Australia has never exported fresh milk to Thailand. It would get stinky before it hit the Bangkok docks. But it’s the raft of other dairy products, in particular, powdered milk that eats into the domestic farm-gate price of Thai milk.

While the average Australian café junkie might throw a tantrum if given powdered milk with their flat white, Thai consumers aren’t so fussy. Cheaper powdered milk is often substituted for fresh milk by retailers knowing that they can skimp on quality, without putting a dent in sales. But it drags down the price of healthier, fresh milk whose sales keep the local industry alive.

“Many farmers have already sold their land in anticipation of hard times,” notes Adul. “Why should we keep risking debt to improve our production when we know we are going to lose?”

Jacques-Chai similarly sees the effect of the FTA as accelerating the tremendous demographic pressures already facing Thailand: “There will be an erosion of the social fabric in the rural areas. Failed farmers will be forced to come to Bangkok. It is already overstretched with a population of 10 million and a third of that is unregistered,” he says.

Perhaps postponing a land-grab invasion of their neighbours, Thai dairy farmers staked their hopes on receiving adjustment assistance from both the Thai and Australian governments. Adul and a dairy farmers’ delegation attended a recent meeting at the Ministry of Agriculture to present a rescue package for their industry. Emerging from three hours of discussion Adul seems dejected: “This government is too cunning,” explains Adul. “There is no plan at all to save our livelihood, our culture, our way of life.”

This was not the case in Australia. When the dairy industry was deregulated in Australia in 1999, the government recognised the risks to farmers and set up the Dairy Structural Adjustment Program (DSAP). Unlike World Bank pushed Structural Adjustment throughout the Third World, the Australian version actually helped some people. Offering nearly $2 billion in benefits, each farm received roughly $120,000 each in government payments since 2000. Even then, many farmers were forced to leave the industry, possibly coaxed by the meager $45,000 exit payout and accelerating the trend into bigger yet fewer farms. About 10,000 dairy farms have disappeared since the early 80s, as family farms have been swallowed up by corporate ones.

Ideally, the Thai dairy industry needs market protection. But under the FTA, an industry assistance package is unlikely to be forthcoming either. Instead, economically unviable farmers will probably be pushed into growing more unprofitable commodities, risking more debt and insecurity.

THE GOLF BETWEEN RICH AND POOR

All this is a steady shift from the promises that swept Thaksin and his Thai Rak Thai (Thais love Thais – TRT) party to power in 2001. Building his Shin Corp business empire in the 1990s, he launched an ambitious political campaign in the wake of the 1997 financial crisis to help the poor and to protect domestic business from predatory international capital. Yet his philosophy has always been profoundly corporate, proclaiming in 1997 that, “A company is a country. A country is a company. They are the same.” Since taking power in 2001 he’s tried to run Thailand like a CEO. Following that logic, it makes sense to use FTA negotiations to promote your high performing sectors and outsource your uncompetitive farmers.

With the rise of Thaksin, politics blurs into business and business blurs into golf games in Thailand. He’s well known to play golf with his inner clique of key party financiers and cabinet members: Prayuth Mahakitsiri, Suriya Jungrungruangkit and Somsak Thepsuthin. The wealth of TRT members is staggering. “They own 40% of the total value of the stock market” says Jacques-Chai. “The Shinawatra family itself owns 10%.” It is easy to picture this quartet of billionaire politicians plotting down the fairway discussing what club to play for this shot and what sector to promote for that FTA.

Perhaps needing an even more private place for their discussions, Prayuth bought his own golf course, paying 1 billion baht (AU$35 mil) in cash in October 2002. Perhaps he had the spare cash floating around because a few months prior, 15 billion baht was questionably shaved off one of his bad debts in a copper smelting project by a government bailout fund. It’s just one example of the pall of cronyism that covers Thai business and politics under TRT.

It hangs particularly strong over the TAFTA. Suriya for example, the Industry Minister from 2001 to 2002 and currently holding the Communications portfolio, stands to profit handsomely from the agreement. As the owner of the Summit auto-parts empire, he is positioned to increase imports to Australia by 30 per cent, according to analysts, when Australian tariff barriers on auto parts are lowered from 40 per cent to 5 per cent next year.

One venture that Shin Corp hopes will make it global is its plan to launch its iPSTAR satellite above Asia, through its Shin Sat subsidiary. It is one of the most advanced satellites, dwarfing existing competition with its huge capacity to provide broadband internet.

But the high risk project was plagued by delays and the political complexities of the region – until Telstra came along. The two companies signed a deal earlier this year where Telstra will build earth stations for iPSTAR in Kalgoolie in Western Australia and Broken Hill in New South Wales in return for a slice of the broadband capacity.

It fits a pattern. FTAs have been an indirect mechanism for Shin Sat to nudge aside its orbital competition. Beijing for example, has moved the orbit position of its own satellites to make way for iPSTAR while Chinese agriculture imports are decimating northern Thai farmers. Shin Sat also recently announced a partnership deal in New Zealand.

Shin Corp also stands to benefit from the near comprehensive liberalisation of the Australian telecommunications sector, raising questions about a possible conflict of interest. “It is difficult to deny this,” says Jacques-Chai. “Australia made an offer to liberalise under the FTA (except on Telstra ownership). They liberalised everything else, especially mobile phones.”

It’s a criticism repeatedly raised by Supinya Klangnarong, the Secretary General of the Campaign for Popular Media Reform. She questions whether the two processes are linked but concedes that, “we just don’t know what they’ve been discussing with the Australian government.” Jacques-Chai also questions what was discussed at an APEC summit meeting late last year between Thaksin and Australian Prime Minister John Howard. “They reportedly had a ‘four eyes’ discussion,” comments Jacques-Chai “and following APEC, there was a significant increase in what Thailand would liberalise.”

Both Shin Corp and the Australian government were quick to counter the allegations of shady dealings, arguing that what Australia offered is no greater than what they offered under the Doha round of World Trade Organization (WTO) negotiations. But WTO negotiations can be glacial points out Jacques-Chai, and the earliest the Doha negotiations could be concluded, albeit very unlikely, is at the next WTO ministerial scheduled for Hong Kong at the end of 2005. Until Australia’s WTO commitments are come online, Thai telecommunications companies get a long head start on other foreign investors. But it’s a trade off that backfired under the China-Thai FTA. Rather than Thai business capitalising on the ‘early harvest’ of China’s markets, Chinese agricultural imports have instead, sent hundreds of Thai small farmers out of business.

Textiles is another sector that the Thai government believes could be a winner. But Jacques-Chai is less certain: “Even studies done by government concede that the textile industry will only see benefits for one or two items: women’s underwear?” But some deals are in the works. T Shinawatra Thai Silk, the original family business of Thaksin, is negotiating a joint venture with an Australian fashion designer, capitalizing on the lower importer tariffs under the TAFTA.

It’ll put more pressure on the already enfeebled Australian textiles industry – hiding behind its shrinking tariff barriers for the last decade. While decent profits are made by retailers and marketers, and probably the Shinawatra Silk venture, it is the exercise of their market power that forces down the wages of both outworkers in back alleyways of Melbourne suburbs and their sisters and brothers in Bangkok’s sweatshops.

FTA’ED

Can Thaksin’s passion for negotiating FTAs – eight are currently on the table – be explained purely as cold hard trade offs? Professor Pasuk Phongpaichit, co-author with Chris Baker of the recently published book “Thaksin: The Business of Politics in Thailand” notes, “I agree that this FTA has dubious benefits, but that is the same for most of the FTAs that this government is pursuing.” She elaborates, explaining that the Government’s “enthusiasm for FTAs has to be explained in terms of politics (because it does not make sense in terms of economics). These agreements are a new kind of international diplomacy, and for Thaksin, are part of his self-promotion on the international stage.”

“This is not the only FTA under which small producers are being sacrificed. It seems to be the pattern,” says Pasuk. For the dairy industry, the precedent set in the TAFTA is coming back to haunt the Thai negotiators, especially in the current negotiations with New Zealand. While Australian competition is stiff, it’s the green pastures of Middle Earth that Thai dairy farmers deeply fear. New Zealand dominates global dairy production accounting for 36% of world trade and they’re pushing for a quicker liberalisation time table under their FTA. Farmers like Chernchai may be buried in the milk powder from Mordor.

Adul and his dairy cohort are businessmen and although bitter about being sold out by the government, realise they must make the best of being FTA’ed: “We would like to use Thailand as a dairy hub for the region and hope to be able to collaborate with the New Zealanders. It’s an opportunity for both sides.” They met with the New Zealand delegation who didn’t endorse this ‘win-win’ optimism. They argued instead that promotion of Thailand’s dairy industry was the job of Thailand’s government.

Jacques-Chai cautions against blaming the sell out of farmers under the FTA purely on the antics of TRT. FTAs instead, are tools of developed countries, like Australia, to pry open the economies of developing countries like Thailand. And it’s larger Thai businesses that are strong enough to capitalise on such liberalisation.

Both liberalisation under FTAs and privatisation fit a pattern of big business filling up the political and institutional spaces left by the waning military bureaucracy. As Supinya laments, “There is a radical liberalisation and we do not have the time to democratise the institutions needed to monitor these processes. We are running from the tiger (the military and the bureaucracy) but are facing the crocodile (big business).”

THAILAND IS NOT SHINLAND

The crocodile was in no mood for consulting on the FTA. Adul, along with many farmers and activists like Jacques-Chai made their concerns known to Government negotiators but got nowhere. “Thaksin never listens to anyone,” says a frustrated Adul.

It was a fight even to see the final document. “The Government only released the text of the FTA after it was released on the Australian Foreign Affairs website,” says Jacques-Chai. “Even then, it was only after public pressure was applied that it was translated into Thai” he adds. He blames Thai Government paranoia. “This approach is a tradition of theirs with international trade negotiations. They don’t want to face resistance and scrutiny that can pick up on alleged conflicts of interest.”

“To organise farmers we held discussions all over the country,” says Adul. “The police asked our dairy co-op meeting to stop otherwise they would take away the meeting’s papers. They said that they had been ordered to do so; to check on the activities of all the cooperatives. All of the president’s of the coops are being pressured this way. We feel that we have lost our freedom of expression and our freedom to milk our cows,” laments Adul.

Such censorship is endemic in a nation where Thaksin – Southeast Asia’s own version of Italy’s Silvio Berlusconi – owns nearly all of the private media and controls all of the government media. Highlighting this crisis, Supinya wrote a paper titled “Communication under Shin’s regime: the conflict of business and political interests” outlining how Shin Corp runs “all aspects of telecommunications, media, computers and satellites.” For her criticism, Supinya could be bankrupted or spend two years in jail – Thaksin’s corporate arm, Shin Corp, has slapped both a civil and criminal defamation suit on her for publishing the paper.

This intimidation is not a bluff. The Government stoked violence in the South of the country, , along with the extra-judicial killing of some alleged 2,500 drug dealers and users in the last two years has spread fear throughout Thailand.

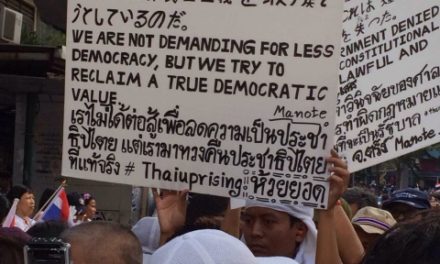

To justify such repression, Thaksin has invoked the “nation” as his “driver”: “Having debates and so many different opinions is just selfishness… Everyone has to unite for the country to progress,” said Thaksin. But “Thailand is not Shinland” as one FTA protest banner points out and thousands took to the streets to underline the point on June 28th, marching to the Government House. A broad range of protestors, from HIV activists to unionist fighting off further privatisation were present, adding to the growing dissent that is eating into Thaksin’s popularity figures. Even major political parties are waking up to the issue, forcing TRT to backtrack and commit to monitoring the impact of the FTA.

Adul is prepared to take to the streets again if farmers are suffering and Thaksin does nothing. “Thaksin will lose government if he doesn’t listen to the dairy farmers.” We start discussing possible actions they could do. What about filling the nearby khlong (canal) with your wasted milk? “Yeah, let the government smell the rotting milk,’ laughs Adul.

But will the smell make it all the way to Canberra? Will a new Australian Federal Senate address these concerns when it comes up for debate or continue its quiet complicity in the shadowy sell-out of rural Thailand?

For more information, visit FTA Watch’s website: http://eng.ftawatch.org

(*) Ben Moxham ([email protected]) works at Focus on the Global South, an activist research centre based in Bangkok Thailand. He is a colleague of Jacques-Chai Chomthongdi. A shorter version of this article first appeared in Spinach 7 Magazine (www.spinach7.com).