The draconian legacy of the 2014 coup d’état continues to haunt the exercise of fundamental rights in Thailand. Although the junta’s restrictions on civil and political rights—including bans on political gatherings—had been lifted to facilitate the 2019 General Election and relevant electoral campaigns, the government retained criminal laws with severe penalties such as the Computer Crime Act, and sections pertaining to Sedition and Royal Defamation. These laws were used as the government’s principal weapons against its critics and their exercise of rights to freedom of expression and freedom of assembly, especially during the 2020-2021 uprisings.[1]

Further in this vein, the Government has introduced a new draft law on the Operations of Not-for-Profit Organizations (NPO law) at the beginning of 2021, which includes intrusive provisions to track the activities and resources of civil society organizations (CSOs) and seeks to impose new controls over civic space. The logic of this proposed legislation has grave implications for civil liberties and the effective implementation of human rights and humanitarian work, not only in Thailand but also in countries served by the range of regional and international organizations that are hosted in Thailand.

Upholding the NCPO legacy

In his second term as prime minister (2019-present, before which he was the junta prime minister), General Prayut Chan-O-Cha continues to rely on repressive legislations and legal actions to maintain power. From 2014 – 2018, General Prayut and the now disbanded coup organization – the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) – centralized the junta’s political and bureaucratic power and control with the issuance of 556 orders that covered: 1) political and civil activities; 2) public information and media reporting; 3) the judicial system including the use of military courts for political cases; and 4) management of natural resources and promotion of industrial development. In addition, there were at least 239 laws enacted without public consultation during the NCPO period including the Public Assembly Act (2015). Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Public Assembly Act has been used widely against pro-democracy protesters along with the alleged violations of the State of Emergency.

In 2021, the rise of the youth-led mobilizations across the country coincided with General Prayut’s order to the Office of Council of State to review legislations on non-profit organizations in other countries, to initiate a domestic law that would directly regulate the non-profit sector in Thailand. In February 2021, the Draft Act on the Operations of Not-for-Profit Organizations was first presented and approved in principle by the cabinet. It contained provisions on mandatory registration of non-profit organizations and criminal liability for not registering, authorized inspections on the use of money and materials (including the authorities’ power to obtain electronic communications, for any reason, and without any suspicion of criminal activity), mandated obligatory financial reporting and disclosure, and appointed the Minister of Interior as oversight authority with reference to non-profit activities. In June the same year, the Cabinet also agreed to add the prevention of money laundering and terrorist financing activities upon recommendation from the Anti-Money Laundering Office (AMLO), which institutes blanket restrictions on foreign funding to non-profit organizations. It may be noted that these restrictions are in contradiction to the international Financial Action Task Force Guidelines[2], which recommends a “proportionate” and “targeted approach” for non-profit reporting in order to allow “legitimate charitable activity to continue to flourish.”

Disputed revision met with public discontent

In January 2022, the Thai Cabinet approved a second draft of the law. The revised draft contains more positive provisions that include the promotion of civil society, the replacement of the regulatory body from Ministry of Interior to Ministry of Social Development and Human Security, the removal of mandatory registration, and the withdrawal of prison term associated with non-registration. While making non-registration an imprisonable offence was clearly a disproportionate punishment, the removal of mandatory registration nonetheless is replaced with Section 20 of the Bill, with broad prohibitions on activities of non-profit organizations. The breach of these prohibitions will be subjected to fines as high as THB 500,000 (USD 14,434) or a daily fine of THB 10,000 (USD 288) throughout the period of the alleged breach, according to Section 26.

Section 20 of the Draft law states that a not-for-profit organization must not operate in the manner that “(1) Affect the government’s security, including the government’s economic security, or relations between countries; (2) Affect public order, or people’s good morals, or cause divisions within society; (3) Affect public interest, including public safety; (4) Act in violation of the law; and (5) Act to infringe on the rights and liberties of other persons, or affect the happy, normal existence of other persons.” However, the definitions of these prohibitions are left to the discretion of officials, including from the military and national security units, who can decide which are the “Bad” CSOs that breach the law.

The requirements on financial disclosure and reporting are also maintained in Section 19 and Section 21, which constitute significant concerns regarding the right to privacy. Section 19 requires NPOs “to disclose information regarding its name, founding objectives, implementation methods, sources of funding, and names of persons involved with its operations to ensure such information is easily accessible to government agencies and the public.” Section 21 asks those that receive funding or donations from foreign sources: “(1) To inform to the registrar the name of the foreign funding sources, the bank account receiving the funds, the amount received, and the purposes for the disbursement of the funds;” in addition to which they “(2) Must receive foreign funding only through a bank account notified to the registrar; (3) Must use the foreign funding only for the purposes notified to the registrar in article (1); and (4) Must not use foreign funding for any activity characteristic of pursuing state power, or to facilitate or help political parties.”

Under the Draft bill, the Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security— as the Registrar— is permitted to order arbitrary actions including the temporary or permanent shutdown of any non-profit organization deemed violating these prohibitions, without any mechanism for due process or appeal. In addition, the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security is authorized to chair and appoint “the Committee on the Promotion and Development of Not-for-Profit Organizations,” where the Committee will procure funding and the Ministry will deposit and decide on the fund’s re-distribution. This Committee also has the power to determine which organizations are exempt from the law. The Ministry’s centralization of regulatory power and the pool of resources, together with the law’s restrictions and penalties, offers Thai authorities the means to discriminate against vocal CSOs. In such a scenario, only the so-called “Good” CSOs could seamlessly operate and have access to Government support.

Although the public consultations on the draft bill was held from late January to April 2022, led by the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security, these consultations were mainly performed online without proactive measures to invite meaningful participation. In response, civil society organizations took a stance to oppose the Draft law through activities including a joint statement co-signed by 1,867 non-profit organizations and a signatory campaign statement challenging the process’s transparency, with more than 14,000 supporters. A public rally was also organized at the Ministry to challenge the tokenism of the consultation process and call on the Government to withdraw all legislations authorizing state interventions that undermine the fundamental rights to freedom of association, assembly and expression.

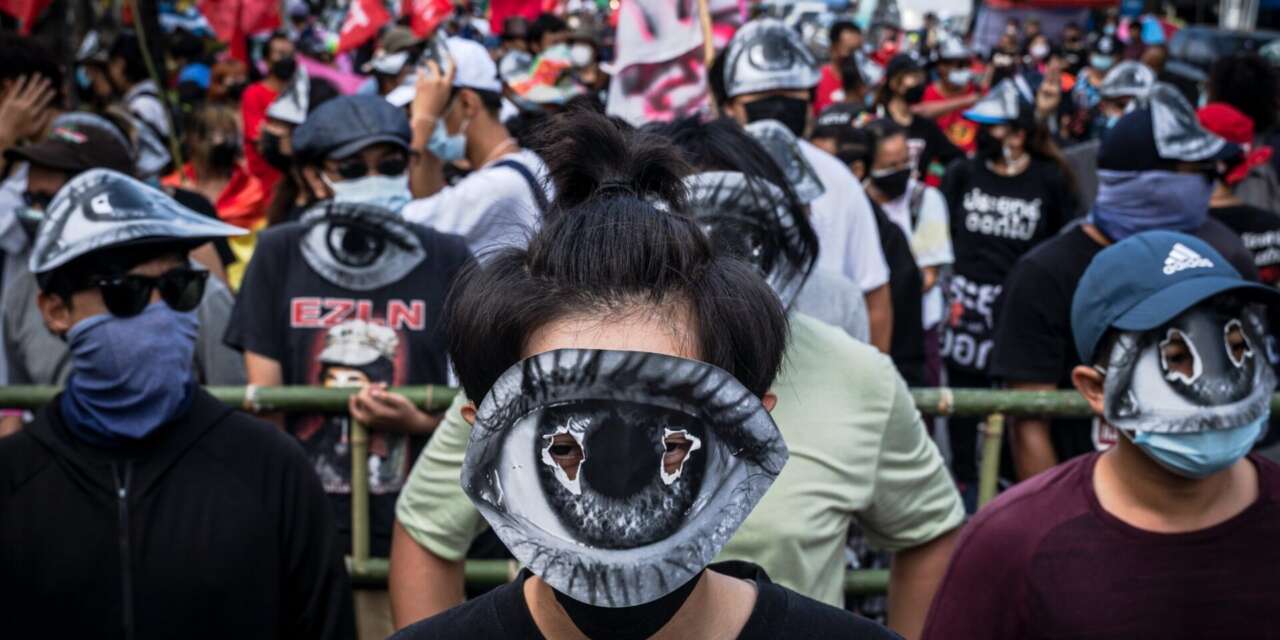

วันที่ 23 พฤษภาคม 2565 เวลา 9.00 น. เครือข่ายคัดค้านร่างพ.ร.บ.การดำเนินกิจกรรมขององค์กรไม่แสวงหากำไร (พ.ร.บ.ควบคุมการรวมกลุ่มฯ #NoNPObill) นัดหมายชุมนุมกันที่หน้าองค์การสหประชาชาติ สะพานมัฆวานรังสรรค์เพื่อเรียกร้องให้รัฐบาลยุติการผลักดันร่างพ.ร.บ.ดังกล่าว. Photo Source: iLaw

The lawfare against public association

At present, it is argued that there are adequate laws and regulations in place to oversee the non-profit sector, such as the tax code, and regulations on human resources and employment. With no clear, acceptable rationale, the Draft law on the Operations of Not-for-Profit Organizations is then both unnecessary and dangerous, as it fuels the risk of intimidation of CSOs rather than ensuring transparency in the sector. It is feared that the Government’s excessive power under the Draft law, together with other repressive legal tools, will interfere with and threaten CSOs, and create burdensome restrictions, especially on financial reporting and disclosure requirements on all forms of people’s initiatives and organizations.

According to the draft law, “Not-for-profit organization” means a collective of private individuals who form themselves as any form of grouping to conduct activities in society without intending to seek profits to be shared.” Given this broad definition, the law in its implementation will bring all kinds of associations —regardless of their sizes and income levels— under the same reporting requirements. For instance, people-led initiatives such as peasant groups, volunteer service organizations, COVID-19 relief initiatives, community clubs, natural conservation groups, as well as groups seeking to defend land and community rights, will be subjected to the same legal requirements as those of international development agencies, public health institutions, human rights groups, and humanitarian organizations. The burden of administrative requirements and unjustified restrictions will inevitably have chilling effects on civic activities and effective delivery of voluntary and humanitarian services.

As an international hub for civil society engagement, the existence of the act will also impact the regional aspect of human rights and humanitarian operations based in Thailand. In particular, reference can be made to efforts responding to the crisis in Myanmar, the effects of hydropower projects on environment and livelihoods in Laos, and the criminalization of human rights defenders in Vietnam, as Section 20 of the Draft act may prevent this important work on the ground of “government’s security on relations between countries.” In this circumstance, human rights organizations supporting the safety and protection of political activists fleeing repressive regimes from around the world will also face risks of shutdown under the same provision.

The Government must end the unjust legislation

After the 2014 coup d’état, the restoration of the rule of law and justice system is a common priority of progressive civil society in Thailand. The NCPO legacy including the network of politico-military officials seated in the parliament, the 2017 junta-drafted Constitution, and other legislative organs and provisions remain grave challenges to democracy and a just society. The Draft law on the Operations of Not-for-Profit Organizations is the latest example how the juggernaut of illiberal institutions could interfere with the rule of law and continue to enact legislations that infringe on human rights.

As a state party to the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Thailand must guarantee civil and political rights enshrined in international law. The Draft Act on the Operations of Not-for-Profit Organizations, with provisions to systematically violate the rights to freedom of association and freedom of expression, must accordingly be withdrawn from the legislative agenda. The Government must also ensure that other proposed laws and legislations strictly adhere to international human rights law and standards, to prevent harmful consequences to civil liberty, safeguard civic space, and uphold the public enjoyment of fundamental rights and freedom in Thailand and beyond.

As a first step, the Government must put every effort to address on-going concerns from civil society regarding the passage of the law. On May 23 – 30, 2022, hundreds of protestors from several groups coming together as “the People’s Movement Against the Draft Laws that Undermine Freedom of Association” had mobilized overnight rallies in front of the UN ESCAP Building, Bangkok, and also marched to the Government House to demand the Government’s withdrawal of the Bill. While the rally could temporarily stop the Cabinet to pass the Draft Act to the Parliament, it is also essential for the Government to assure future transparency of the legislative process and to take proactive steps to reconsider the necessity of such legislations and their potentially devastating effects on civic space.

———

[1] The 2020-2021 youth-led protest is a series of mobilizations that happened across Thailand after the Constitutional Court dissolved the Future Forward Party. The mobilizations present three demands that included: 1) the resignation of PM General Prayut Chan-O-Cha, 2) the dissolution of the parliament, and 3) the reform of the monarchy. The Government’s (mis)management of the pandemic, especially on its failure to procure quality vaccines, helped fuel public anger and drive the growth of pro-democracy supporters. The uprisings brought together hundreds of thousands of pro-democracy supporters all over Thailand, and despite resort to legal persecutions using “lèse majesté” and other political charges on protestors, the Government could not halt the mobilizations.

[2] Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is an intergovernmental organization that tackles global money laundering and terrorist financing activities.