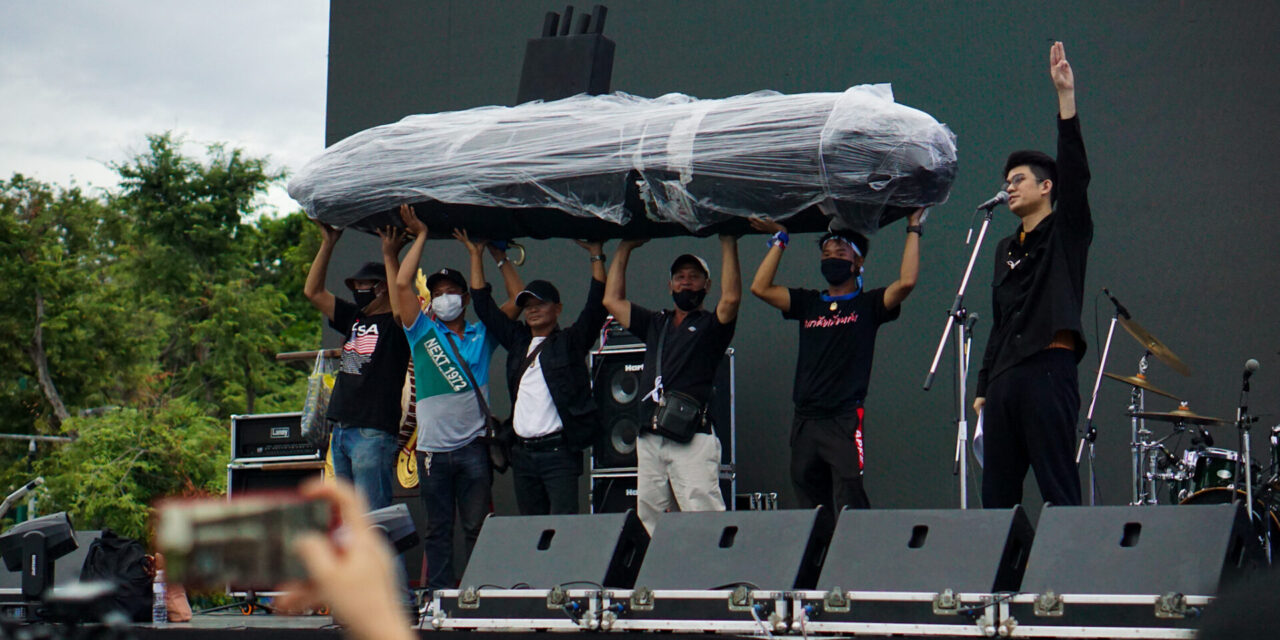

A series of political uprisings in Thailand has entered its fourth consecutive month, and the spirit of resistance still shines bright. Led by students from universities, high schools, and even middle schools across the country, these mobilizations will unquestionably become another historic page Thailand’s modern history. In a short period of time, this fast-growing movement has expanded not only in numbers but also in terms of geography and demography, gaining the support of people across professional, economic, and political lines.

Despite the diversity of their backgrounds, participants in the movement have stood united around three demands: the dissolution of parliament, reform of the constitution, and reform of Thailand’s monarchy. After six years of junta and semi-dictatorial rule, the growth of the oligarchy and the government’s political and economic incompetence are indisputable.

The protest movement’s first two demands, therefore, came as no surprise. By garnering public support from , the protesters hope to topple the government of former general Prayut Chan-o-cha and the handpicked appointees who keep him in power – senators, the constitutional court, and the independent regulatory agency.

The third demand, however, surprised everyone. Neither veteran activists, political analysts, nor even the protesters themselves could have predicted the strong support within the movement for calls to “ ” that stifles free discussion of the monarchy and prevents accountability.

These unprecedented demands for monarchical reform and the growing effectiveness of the protest movement can be better understood in the context of the events leading up to the first mobilization, as well as other underlying factors that laid the groundwork for the movement.

Immediate causes

Anti-government sentiment has been in the air in Thailand since the beginning of 2020, when thousands of people registered to “Run Against Dictatorship”. Then, in February 2020, the Constitutional Court ordered the dissolution of the progressive Future Forward Party, of rallies at schools and universities across the country.

That same month, Thailand became the first country to confirm a COVID-19 case outside China – a result of the Prayut government’s refusal to close the borders or enforce a lockdown. Around the same time, a government minister and officials were found to have been hoarding medical masks and exporting them to China. In March, an army-owned boxing stadium defied government lockdown orders and held a match attended by 5,000 people, leading to more than 130 COVID-19 infections.

These scandals compounded existing public outrage over previous corruption scandals in the years following Thailand’s 2014 coup, such as the discovery of Deputy Prime Minister General Pravit Wongsuwan’s collection of luxury watches.

Throughout March, demonstrations steadily grew while daily infection rates . The government eventually declared a state of emergency, ostensibly to curtail the spread of the virus. However, the decree also had the effect of pausing Thailand’s youth-led democracy movement.

Thailand has recorded no community transmissions of COVID-19 since May. However, the working class has paid a heavy price for the “stay at home, save the nation” policy that has made this possible. The Attorney General’s Office recorded 26,200 violations of lockdown orders within the first three months. With international tourists banned, thousands of small and medium businesses that depend on foreign customers have suffered. In the first half of 2020, the suicide rose by 22 percent compared to the same period last year, which is thought to be linked to pandemic-induced stress and poverty.

It is important to note that the state of emergency decree the government has deployed to curb the virus is the same sort of decree that has been used to maintain “peace and order” in Thailand since the military coup in 2014, perpetrated by the current prime minister. After taking power, the junta imposed martial law, banning political gatherings and activities, prosecuting critics, and censoring the media. Rights groups have documented more than 2,000 trials of civilians by military courts in the five years of military rule for violations of military orders and other high-penalty charges, including lèse-majesté and sedition. Computer crimes and violations of the Public Assembly Act have also been widely applied to suppress peaceful expression and mobilization.

In June, the abduction and disappearance of pro-democracy activist Wanchalearm Satsaksit aroused collective anger, both online and offline. Despite zero domestic cases for more than a hundred days, new infections linked to the arrival of Egyptian and Sudanese diplomats, who were admitted into the country through the government’s “VIP guests” exception and subsequently flouted safety measures. This brought the people back into the streets.

Mass political education

However, these mobilizations have not merely been reactions to particular events. For several years, young people in Thailand have been studying other pro-democracy movements and building an online infrastructure for their own.

This fact is evident in the protestors’ strict adherence to non-violence as they expose the country’s abnormal political structure, including its most taboo element – the monarchy. Their strategy draws on deep understanding of Thailand’s politics, economy, history, constitutional processes, and human rights commitments and instruments, as well as of other global civic movements and ongoing intellectual debates. The movement reflects the political learning processes that Thai youth have been undertaking with the use of online educational resources, including social media.

It is undeniable that social media has played a critical role in facilitating the mobilizations. #MilkTeaAlliance and countless other hashtags on Twitter have drawn material and amplified the protestors’ demands and instigated public debate, both locally and internationally. Rights groups and news agencies have also been able to collect and broadcast the protestors’ messages and activities through Twitter.

Moreover, Facebook remains the go-to platform for high-profile Thai critics and political exiles, such as Somsak Jeamteerasakul and Pavin Chachavalpongpun, who continuously post critiques of the monarchy. As the military tightened its grip on power between the death of King Rama IX and the coronation of the current King Rama X, the social media accounts of these prominent Thai exiles became the main source of information about the monarchy. Their effectiveness was recognized by the government in 2017, when Thailand’s Ministry of Digital Economy and Society banned online contact with these exiles. This year, the Facebook group Royalist Marketplace, run by Pavin Chachavalpongpun, attracted more than a million members with its offering of “brain-awakening” book recommendations.

Rights groups, pro-democracy activists, media outlets, and progressive political parties must also be recognized for their roles educating the public on the meaning and methods of resistance. The Future Forward Party, despite being outlawed in February 2020, galvanized the democracy movement and promoted inclusiveness in politics and policymaking. iLaw, Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR), and media outlets such as Prachatai all helped broadcast progressive analysis and advocacy tools. Pro-democracy activists such as the Democracy Restoration Group (DRG), 24 June, and Dao Din have all shared their know-how with the current mobilizations.

Finally, academics, progressive publishing houses, and groups advocating for reforming the monarchy have all contributed to the unprecedented willingness among Thais to demand such reforms. While the general population vents its disdain for the royal family’s long stays in Europe and unseemly behavior, these groups been working to provide analysis of the monarchy as an institution and to propose concrete policy recommendations. On 10 August 2020, students at Thammasat University released 10 demands based on the eight-point declaration issued by Somsak Jeamteerasakul in 2010.

While the aforementioned factors help explain why the youth-led mobilizations coincided with the rise of the military regime and the COVID-19 pandemic, there were also pre-exiting factors, such as the crushing of the Red Shirt movement, the marginalization of certain communities, state-backed political violence, impunity, and an overall lack of social justice. These factors are still in need of further analysis. Furthermore, the social processes by which various groups developed their political aspirations and began organizing constitute another avenue for inquiry necessary for understanding the current mobilizations.