2024 September 6

Text and photos by Galileo de Guzman Castillo

ENDURING. Originally built in 1915, the Genbaku Dome was the only (skeletal) structure left standing in an area about 160 meters away from the hypocenter of the first atomic bombing in 1945. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. 2024 August 4.

Give back my father, give back my mother;

Give grandpa back, grandma back;

Give my sons and daughters back.

Give me back myself,

Give back the human race.

As long as this life lasts, this life,

Give back peace

That will never end.

—“Give Back the Human” by Sankichi Tōge, hibakusha

English translation by Miyao Ohara

Last month, the 2024 edition of the annual World Conference against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (“World Conference”) was held in the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan. Organized by Gensuikyo (Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs), the World Conference has been a space for the convergence of Japanese and international movements for almost 70 years already, with the participation of activists, students, and civil society working collectively for peace, justice, and democracy. An estimated 4,000~ participants joined from all over Japan and across the world, including overseas peace activists, grassroots organizations, foreign diplomats, and representatives of international agencies and national governments, among others.

Representing Focus on the Global South and being one of the International Youth Relay Peace Marchers, my roles throughout the World Conference included co-chairing the Nagasaki Day Rally and serving as one of the panel speakers at the Youth Forum in Hiroshima. My message of peace, justice, and solidarity was also shared during the International Meeting. But most of the time, I was a “sponge” taking everything in from my first-ever World Conference—learning from the various people I met and the enriching interactions I had—especially with the hibakusha (atomic bombing survivors).

REVERBERATING. Thousands of national and international delegates converge for the Hiroshima Day Rally of the World Conference, displaying pennants (expressions of solidarity) collected from local governments in various Japanese prefectures. Green Arena, Hiroshima Prefectural Sports Center. 2024 August 6.

Held on the eve of the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombings in 1945, the World Conference this year has even greater significance for conveying the hibakusha’s voices across the world towards the realization of the common aspiration for lasting peace and a nuclear-free world in their lifetime (the first generation hibakusha’s average age now stands at 85+ years). This lifelong commitment was underscored in the message of Hisaikyo (Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Survivors Council): “We will continue to call for the abolition of nuclear weapons until the day we die.”

The World Conference also took place against the backdrop of intensifying wars and conflicts, continued occupation, greater push for militarization, and rising global militarism—as the world teeters on the cusp of a potentially uncontrolled nuclear arms race stoked by warmongers. The ongoing genocide of Palestine by Israel has been raging for almost a year now, and with it, nuclear powers and their allies have continued to cling to the flawed (and suicidal) doctrine of “nuclear deterrence.” In various declarations, political leaders of the Global North, particularly the Group of Seven (G7) in their “Hiroshima Vision on Nuclear Disarmament” ironically argue that nuclear weapons—for as long as they exist—“deter aggression and prevent war and coercion.”

CAPTIVATING. World Conference delegates are enthralled by the presence of “true marchers”—those who walk the entire 1,800-kilometer Peace March from Tokyo to Hiroshima—Kobayashi-san and Ohmura-san as they go up the stage. Green Arena, Hiroshima Prefectural Sports Center. 2024 August 6.

In the name of “peace,” “development,” and “order,” various states have justified more military spending, gutting much-needed public resources for education, health, social services, and climate emergency response. The continued expansion of military alliances and joint operations has only deepened the acquiescence (subservience) of governments to the demands and whims of superpowers. Justifying the “need” to strengthen security links and commitments between the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the Indo-Pacific,” states from both the Global North and Global South have engaged in a series of joint military exercises and multilateral maritime cooperative activities to promote a “rules-based order” and “much greater convergence” in different regions.

It was in this context that the plenary sessions, workshops, and associated events of the World Conference served as a rallying point to collectively discuss, strategize, and galvanize support for various campaigns and struggles. These involved discussions on the promotion of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW)—currently supported and ratified by mostly Global South states—as well as the continued campaign for the implementation of Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) Article VI and further expansion of Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones (NWFZ) as have been realized in Africa, Southeast Asia, Central Asia, South Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean.

QUESTIONING. An audience member in the Youth Forum asks how one can start a dialogue with people who have different political persuasions and values (e.g. on the issue of nuclear power as “clean and alternative energy”). Small Arena, Hiroshima Prefectural Sports Center. 2024 August 5.

The World Conference also facilitated meaningful exchanges among different groups across different generations through, among others: 1) interfaces with government officials such as nuclear disarmament leaders of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and progressive political parties in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN); 2) testimonies from the hibakusha and learning firsthand about their experiences and continuing struggles against discrimination; 3) bahaginan (sharing) among grassroots communities, peace marchers, and regional and international networks carrying out various solidarity actions and translating peace initiatives into concrete practice; 4) linking of cross-sectoral and intergenerational struggles on peace and security, gender and climate justice, democracy and human rights; 5) cultural visits and learning sessions on peace-building (through films, music, and other forms of creative expressions).

In the Nagasaki World Conference, chargé d’affaires of the Cuban embassy in Japan, Dairon Ojeda emphasized the unavoidable duty of preserving international peace and security initiatives by the Non-Aligned Movement. According to him, the international community “cannot remain passive in the face of greater polarization” and that the prevailing order should not distract us from achieving practical commitments (such as ratifying TPNW) for a world without nuclear weapons.

His remarks came after the overt hypocrisy and double standards around “rules-based order” and “values-based regime” displayed by the G7 in their snub of Nagasaki’s peace memorial ceremony—as a response to the action of Mayor Shirō Suzuki who disinvited Israeli representatives from the annual peace event.

MOVING. Hibakusha Yokoyama-san and Kakita-san of Hisaikyo in Nagasaki share their stories and experiences of surviving the atomic bombing. The Nagasaki Citizens Peace Charter of 1989 states: “Reflecting upon the actions of our predecessors in past wars and remembering the unending sufferings of the atomic bombing survivors, we resolve to ensure that Nagasaki is the last place on Earth subjected to the horror and misery of a nuclear holocaust.” Hisaikyo Headquarters, Nagasaki. 2024 August 8.

What was emphasized throughout the official and civil society events was the imperative to build unities, alliances, and solidarity among civil society, peoples’ movements, and government officials. This has been demonstrated in various local struggles, for instance with the initiative, “Mayors for Peace” that now enjoys the support of 8,417 member cities in 166 countries and regions and continues. Similarly, at the international level, various groups have advanced the nexus of peacebuilding and human rights through the UN and its special mechanisms. All these initiatives have actively supported peoples’ endeavors to raise peace consciousness beyond boundaries.

Moreover, with the convergence of different movements, the World Conference has also made stark the importance of linking various peoples’ struggles and working hand in hand for a more just, sustainable, and peaceful world. For one, as landmark nuclear cooperation agreements are inked in the name of “clean energy transitions”—facilitating the export for nuclear material, equipment, and components—there is growing need for anti-nukes, ecological justice, and peace movements to come together and organize collectively. In the same vein, there can be no climate and environmental justice without gender justice—thus, movements must stand in solidarity with the struggles of Okinawans and resist together against the construction of new military bases (with most recent being the massive naval and air base in Henoko) and the cover-ups of sexual assaults by U.S. servicemen against Okinawan women.

OVERWHELMING. Peace and security for whom? Busloads of police personnel deployed by the government arrive for the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony, where Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida will be delivering a speech. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. 2024 August 6.

The World Conference served as a testament that building strong and intergenerational communities of peace activists requires humility, patience, and willingness to pass on one’s knowledge and wisdom through exchanges (which also means listening and learning from each other). A poignant and powerful moment transpired during the World Conference during the reading of speeches by the late hibakusha and anti-nuclear movement leader Senji Yamaguchi at the United Nations (UN)—one of which when he, a survivor of the nuclear inferno in Nagasaki—rhetorically asked the General Assembly “whether this kind of genocide should ever be allowed to happen again?”

At the same time, the World Conference also served as a space to expose the contradictions we confront in our collective struggles, among others: of why Japan has not ratified the TPNW despite being the only country that has directly experienced the horrors of atomic bombing; of why busloads of police personnel were deployed for a peace commemoration that was likewise cordoned off and tightly controlled; of why a country that has renounced war—as explicitly enshrined in its Constitution—continues to maintain a self-defense force and ramp up military spending.

As I found myself reflecting on the above, I was also left wondering at the conclusion of the 2024 World Conference: “So, where to from here?”

GALVANIZING. Rex Alex of the State University of New York- Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (SUNY-BDS) Movement and other World Conference participants gather expressions of solidarity and public support for the signature campaign to call for the ratification of the TPNW. Hamanomichi Arcade, Nagasaki. 2024 August 9.

Political sociologist Paul Joseph points a direction forward: “The attraction of common security and peacemaking should not be sugarcoated with platitudes. Promising to wave a magic wand only obscures the hard work required to overcome differences, many of which are real.” He adds, “While recognizing the importance of pragmatic considerations in peacemaking, we never want to overlook the spirit and faith that enable people to move past the chosen traumas.”

As the flames of war are persistently stoked by the elites, tyrants, and military-industrial complex, may we all remain steadfast in our determination to rise from the ashes of conflagrations—overcoming differences and moving forward, together. And, as the convergence of peoples and movements in the World Conference has shown, collective actions and unwavering solidarity can do wonders in bringing about meaningful change: by raising political consciousness, by shifting narratives, by concretizing actions—for systemic transformations, for just and lasting peace.

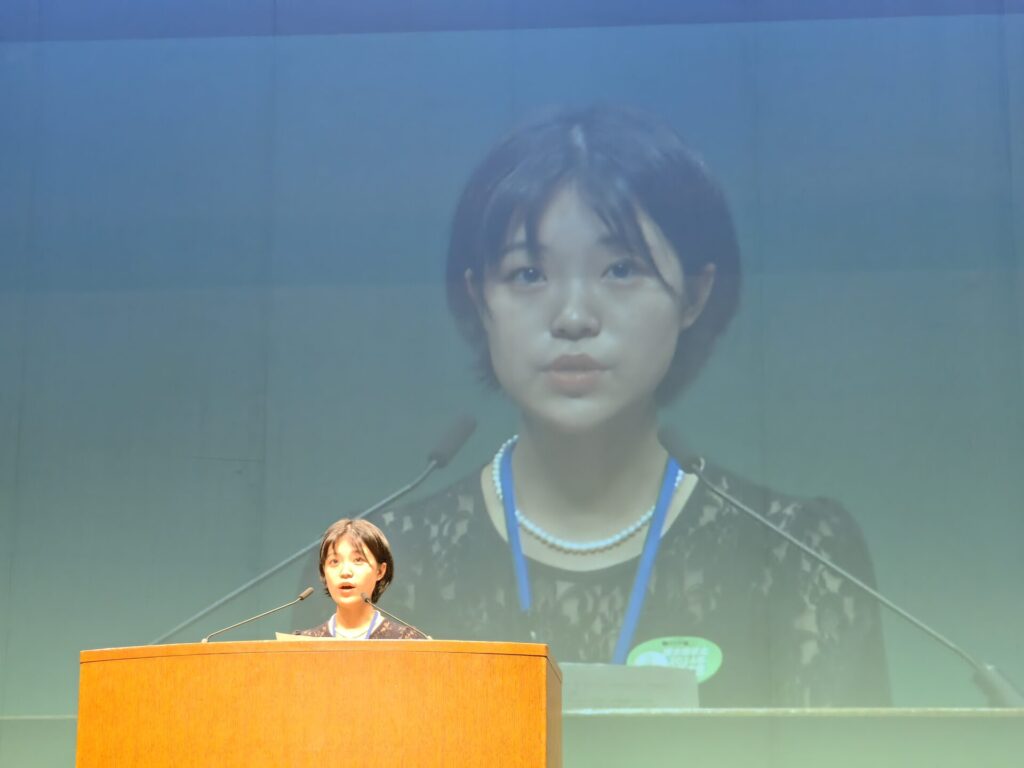

HEARTENING. Tanaka Mitsuki-san (above) and Kogusuri Gaku-san (below) prove that “the kids are alright” as they read the Hiroshima and Nagasaki World Conference Declarations. Both Gensuikyo young volunteers also interpreted for the international delegates throughout the World Conference. Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. 2024 August 6 and 9.

ILLUMINATING. “Now is the time to turn the tide of history, to get beyond the hatreds of the past, uniting beyond differences of race and nationality to turn distrust into trust, hatred into reconciliation, and conflict into harmony,” says one hibakusha as referenced by Hiroshima Mayor Matsui Kazumi in the City’s Peace Declaration. Peace Lantern Floating Ceremony, Bank of Ota River near Aioi Bridge, Hiroshima. 2024 August 6.

COMPELLING. Peace waves from the Philippines and Japan to Palestine. The author (left) with Japanese youth volunteer Yuki-san (wearing artivist AG Saño’s hand painted Palestine solidarity shirt). Yuki-san cycled from Hiroshima to Nagasaki (~420 kilometers) to join the World Conference. Nagasaki Shimin Kaikan Gymnasium, Japan. 2024 August 9.