A year after the Lumad (indigenous people’s) killings in Lake Sebu, South Cotabato, and still no justice in sight, Task Force TAMASCO asks the Department of Environment and Natural Resources where its interests lie and whose agenda it serves. Quezon City, Philippines. 2018 December 3. Photo by Galileo de Guzman Castillo.

“Mother Nature—militarized, fenced-in, poisoned—demands that we take action.”

—Berta Cáceres, Honduran environmental activist killed in 2016 for defending indigenous people’s rights and leading the struggle against the Agua Zarca Dam

By Galileo de Guzman Castillo

Nature abhors a vacuum and likewise it must loathe empty promises. Since the beginning of his electoral campaign in 2016, President Rodrigo Duterte has been indulging in a lot of populist promises. At the onset, he openly stated his opposition against open-pit mining, promised to halt environmental destruction, pronounced support for the crafting of a law on sustainable land use, vowed to transform the country’s energy system by phasing-out coal, and ensured the protection of indigenous communities. These statements earned him not only the support of environmental advocates, but also the votes of some progressive groups and sections of the Left. Pinning their hopes on a perceived able and nonconformist leader, many of them ventured into critical engagement with the Duterte administration from its inception.

However, the conflicts and contradictions gradually manifested as the government remained beholden to corporate power and interests. Duterte began abandoning previous populist stances wherever they were inconvenient, in an increasingly obvious pendulum swing towards further entrenchment of neoliberalism in the policy arena, including that of the environment. Everything that ran counter to Dutertenomics, the corporate-driven and market-oriented economic agenda of the administration, were swept aside. Environmental policy and action were not taken in their own right but through the lens of prospective investments, tourism revenues, and trade flows. Key green legislation such as the National Land Use Act, Alternative Minerals Management Bill, and Forest Resources Bill remained in limbo. Duterte’s unabated addiction to coal and entertainment of Russian interest in reviving the mothballed Bataan Nuclear Power Plant has stymied the Philippines’ just transition to renewable energy.

The non-confirmation of then Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) Secretary Gina Lopez, after she ordered the closure and suspension of 26 mining firms and lifted the moratorium on new mining permits, perhaps served as the turning point—a strong indication that Duterte was disinclined, as scholar-activist Walden Bello puts it, to break-up with the Mindanao Mining Mafia that helped propel him to the presidency.[ii] Lopez’s kicking of the hornets’ nest and eventual non-confirmation exposed Duterte’s non-existent policy agenda on the environment. This has translated to a further opening up of the Philippine economy to state and corporate extractivism, against a backdrop of worsening violence and impunity.

In 2017, Focus on the Global South unpacked Dutertismo and described the administration’s governance of the environment as “laban-bawi” where one positive step forward is rendered meaningless by a regressive countermove.[iii] Red flags were raised on the intensifying threats to the environment and the commons brought about by massive infrastructure investments under the government’s Build Build Build program, particularly those tied up with extractives and Chinese loans. Things took a turn for the worse in 2018 when the Philippines was tagged as Asia’s deadliest country for environmental defenders by international watchdog Global Witness in its 2017 report, “At What Cost?”, with 48 individuals killed (a 71% increase from 2016) under Duterte’s destructive, divisive, and despotic rule. More and more indigenous people face illegal arrests, forced displacement, and death threats for defending their ancestral lands and domains. Mindanao remains a battleground for competing interests and agendas—a site of rampant human rights violations, aggravated by the declaration and subsequent re-extensions of martial law on the entire island. More than two years in office and nothing concrete has come out of Duterte’s populist rhetoric on environmental protection and climate change mitigation.[iv]

Halfway into his six-year term, Duterte’s initial populist posturings have hardened into shades of authoritarian populism. As dominant elite political and economic interests rear their ugly heads, the government seems to have acquired a split personality whereby it can shrug off the impact of policy decisions on the environment and local communities, but at the same time paint specific and localized environmental issues as an “emergency crisis”, with the Chief Executive morphing into an “environmental crusader”, flexing the government’s muscles to step in via a strongman approach, and imposing authoritarian control and dictatorial rule.

Bawi-bawi (grab and seize)

When we look at how the government and those in positions of power view the environment, regard nature, and fail to grasp the urgency of the climate crisis, we begin to see more and more the insidious shift of the “laban-bawi” style to “bawi-bawi”. This may mean forcibly taking away land from smallholder farmers, peasants, and rural women; fishing grounds from artisanal fisherfolk; sources of livelihood from agricultural, migrant, and fishery workers; woodlands from forest dwellers; and ancestral lands and domains from indigenous peoples. This kind of governance ensures that nature is stripped of its intrinsic and ecological value, that extractivism and corporate plunder prevail, and that decision-makers and policy managers completely withdraw from real and systemic solutions. In its ugliest form, “bawi-bawi” enables the perpetuation of the dominant, exploitative economic paradigm, and allows the unrelenting oppression of people and domination over nature.

Perhaps the most emblematic “bawi-bawi” case in recent memory is the closure and redevelopment of Boracay Island. Admired worldwide for its pristine white-sand beaches and regarded as a top tourist destination in the Philippines, the island faced serious environmental degradation caused by overcrowding, overflowing garbage, untreated sewage, non-compliance by businesses with environmental laws, and illegal development activities. “I will close Boracay. Boracay is a cesspool,” Duterte declared at a business forum in Davao City in February 2018. Two months later, he ordered the island’s six-month closure from April to October, affecting over 36,000 jobs and an estimated ₱56 billion ($1.7 million) in revenues. Boracay’s stakeholders argued that the solution did not need to be a unilateral closure of the entire island, but only of the business establishments that violated local environmental regulations and national laws such as the Clean Air Act of 1999, Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000, and Clean Water Act of 2004.

While there was no question as to the necessity of rehabilitating Boracay, the manner in which it was carried out was unconstitutional as it violated the right to travel and the right to due process, intruded into the autonomy of local government units, and was an impermissible exercise of police power by the President. In his dissenting opinion on the 11-2 Supreme Court en banc decision that upheld Duterte’s Proclamation No. 475 declaring a state of calamity in Boracay and ordering its closure, Justice Benjamin Caguioa argued, “This ponencia, which prioritizes swiftness of action over the rule of law, leads to the realization of the very evil against which the Constitution had been crafted to guard against—tyranny, in its most dangerous form.”[v] The only other dissenter, Justice Marvic Leonen maintained, “Authoritarian solutions based on fear are ironically weak. We still are a constitutional order that will become stronger with a democracy participated in by enlightened citizens. Ours is not, and should never be, a legal order ruled by diktat.”[vi]

Political scientist Denise van der Kamp describes this style of governance, also observed in Russia, Latin America, and Southeast Asia, as “blunt force regulation”: states engage in short term solutions to regulatory problems that seem rash, heavy-handed, and counter to leaders’ political interests.[vii] With the perceived success of the Boracay rehabilitation, the government plans to apply the same tactics to similarly popular tourist destinations like El Nido and Coron in Palawan, Panglao Island in Bohol, and Siargao in Surigao del Norte.

Another controversial project is the ₱47-billion ($900-million) Manila Bay “Rehabilitation” plan, with no less than the DENR Secretary Roy Cimatu pronouncing, “The next war we are going to wage is against Manila Bay.” The same modus operandi is being planned, despite stark differences between the two cases: Boracay covers an area of 10.32 km2, while Manila Bay spans an area of 1,994 km² (193 times larger) bounded by six highly-urbanized cities of Metro Manila: Las Piñas, Parañaque, Malabon, Navotas, Pasay, and Manila, and the provinces of Cavite, Bulacan, Pampanga, and Bataan, with about 5 million residents living in the coastal areas compared to Boracay’s 50,000 estimated population.

According to urban planner Felino Palafox, Jr., rehabilitation efforts should be based on the principle of triple bottom line—people first, planet Earth, and then the economy. He states, “The formulation of a comprehensive master plan (CMP) is immensely crucial. Rehabilitation plans must be cohesive in an integrated overall framework. Focusing on the metropolitan region alone would be disadvantageous because this would not address the root causes of environmental degradation in adjacent areas.”[viii] As Pablo Rosales, fisherfolk leader of PANGISDA-Pilipinas (Progressive Alliance of Fisherfolk in the Philippines) and the broader Movement for the Pro-People Rehabilitation of Manila Bay asserts, “Manila Bay needs more than a ‘cosmetic clean up’—a truly sustainable and pro-people plan that considers the lives and livelihood of those that depend on it.”[ix]

Manila Bay rehabilitation for what, for whom, and how? Photo by Patrickroque01. Retrieved from English Wikipedia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Metro_Manila_view_from_Manila_Bay_-_Makati_and_Pasay_(Fort_San_Felipe,_Cavite_City;_2017-04-03).jpeg), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode

But here’s the rub.

In the absence of a clear policy agenda, a conscientious effort, an inclusive plan, and a systemic approach, the people are left with Duterte’s maverickism—resorting to “shock and awe” tactics, invoking graphic images of “emergency crises”, and carrying out “necessary wars” to solve them. Under this administration, dealing with crises justifies drastic moves: extreme solutions are made acceptable. Drawing from the administration’s flagship domestic policy—the war on drugs—the same methods and approach are applied: punishing, unrelenting, and tormenting

Even more sinister is Duterte’s penchant for a militaristic approach, appointing ex-military men to government posts because, supposedly, “they get the job done”. Examples are DENR’s Roy Cimatu and another former general, Eduardo Año, of the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG). With little or no regard to processes—including consultations with affected communities—government decision-makers turn a blind eye to the long-term costs and implications of the blunt force approach. Access to the commons is forcibly denied and people’s jobs and sources of livelihood are sacrificed, forcing many to migrate against their will and acquiesce to unjust relocation and compensation arrangements, if any.

Key questions are posed: Does the government support community welfare and ecological sustainability or does it support neoliberal, pro-corporate development at the expense of the environment and the people? Who are the key players and what are the real motivations behind particular policy positions of the administration? Is the blunt force approach a justified way of solving environmental crises? As Duterte’s political and economic interests and agenda vis-à-vis environmental policy are unmasked, it becomes harder and harder to resolve the glaring contradictions between his earlier populist pronouncements and the actual responses, actions, and realities on the ground as in the cases of Boracay and Manila Bay.

Currently, there are 19 reclamation projects in Manila Bay: 12 are in the application stage, six in detailed engineering stage, and one in implementation stage. One reclamation project, the 265-hectare Pasay Harbour City worth ₱62-billion ($1.18-billion), was awarded to a consortium comprised of Udenna Development Corporation (UDEVCO), Ulticon Builders, and China Harbour Engineering Company Limited. Davao-based businessman Dennis Uy is the founder and chairman of Udenna Corporation and is a close friend of the President.

Just a few days after the Manila Bay rehabilitation started in January 2019, Duterte issued an Executive Order that transferred the power to approve all reclamation projects to the Philippine Reclamation Authority, which he also housed under the Office of the President. For the fisherfolk of Manila Bay, who were not consulted and included in the government’s plans, this signalled their death knell. For the longest time, they have been opposing waterways grabbing in the name of “progress”, and reclamation couched as part of “rehabilitation”. Neither can be considered good development—one that is non-destructive, non-extractive, and serves the interests of communities over corporate and political elites.

The residents of Boracay are raising similar concerns: Was the clean-up of the island really done for the sake of the environment and the people, or was it really to level it up as a gaming resort and attract bigger private investments?

Whose agenda and interests ultimately underpin all of the government’s high-profile cleaning up and rehabilitation of the environment?

Laban-laban (struggle and fight)

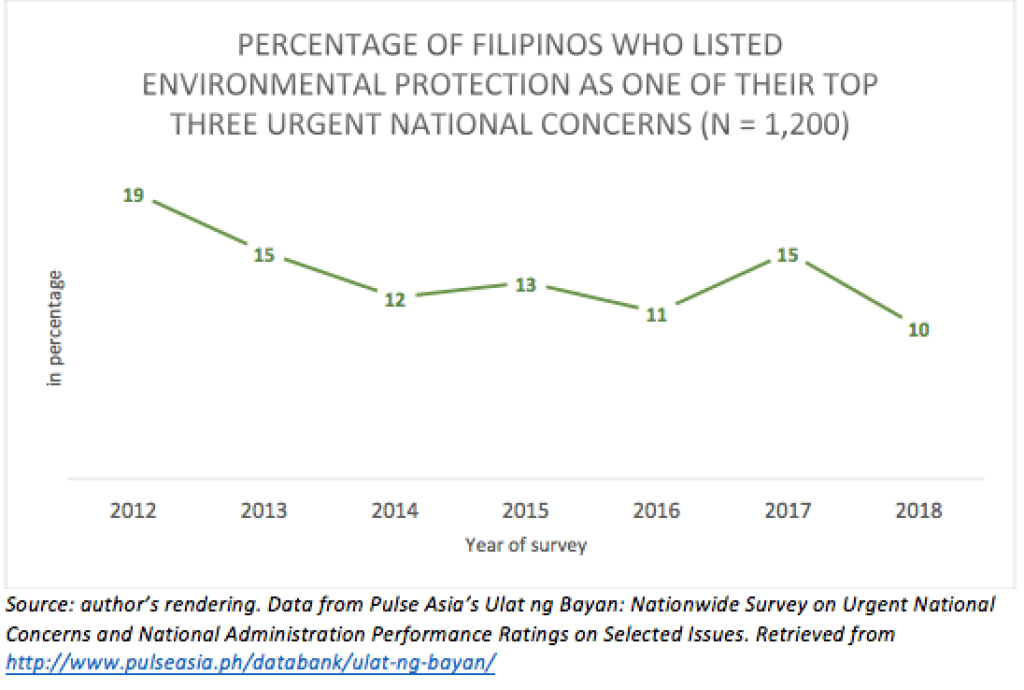

In a recent Pulse Asia Survey,[x] 13% of Filipinos (based on a sample of 1,800 representative adults, 18 years old and above, ± 2.3% error margin at the 95% confidence level) included “stopping the destruction and abuse of our environment” as one of the top three urgent national concerns they believe the administration must address. This sentiment has remained essentially unchanged for the past six years, spanning the equivalent of one presidential term. Interestingly, when broken down to socio-economic status and geographical demographics, those under Class E (lowest socio-economic status) and the provinces (outside the National Capital Region) consistently gave higher priority to environmental protection throughout the years

The Philippines is no stranger to climate change and its impacts, consecutively ranking in the top three of the World Risk Index.[xi] Those in the affected communities, especially women, bear the brunt of the impacts of extractive industries, the consequences of the government’s decisions, and the costs of climate change both to the economy and other aspects of society.

Metro Manila, for instance, is a clear case of a ticking time bomb. In their 2017 report,[xii] the Asian Development Bank and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research named the 25 cities most exposed to a one-meter sea-level rise, 19 of which are located in the Asia-Pacific region. In the Philippines, seven cities—including four in Metro Manila: Taguig, Caloocan, Malabon, and Manila—are in danger of being inundated. As early as the 1970s, there was already a forewarning of this problem as pointed out by the Metro Manila Transport, Land Use, and Development Planning Project—a plan that has never been implemented. Ever since, the government’s plans have pointed more towards prioritizing economic gains over fortifying communities against sea-level rise, achieving social equity, and ensuring environmental sustainability.

There is an overwhelming consensus that climate change is the greatest challenge of the present generation, and addressing it should be the world’s topmost priority and a collective responsibility. While the issue of climate and environment is oftentimes discussed as a transboundary, global, and existential issue on the international stage, the most important and critical struggles for climate and environmental justice are being led by common folk—people who are valiantly resisting so-called “development projects” in their communities.

For instance, the ₱18.72-billion ($354.91-million) New Centennial Water Source Kaliwa Dam and the ₱4.37-billion ($82.85-million) Chico River Pump Irrigation Facility, both China-backed and masked as “development projects”, will have deleterious impacts on the environment, the commons, and the local people. The former will submerge five barangays in the Province of Rizal and two more in Quezon, including the ancestral domain of the Dumagat-Remontados, uprooting them from Sierra Madre. The latter will put farmland and indigenous communities in Kalinga under water—a project that dates back to the Marcos dictatorship in the 1970s, when the villagers opposed the then proposed World Bank-funded Chico River Basin Dam that was eventually scrapped following the murder of Butbut tribe leader Macli-ing Dulag. Indeed, as the World Commission on Dams reported as early as 2000, “while dams have made an important and significant contribution to human development,” in “too many cases, an unacceptable and often unnecessary price has been paid to secure those benefits, especially in social and environmental terms, by people displaced, by communities downstream, by taxpayers and by the natural environment.”[xiii]

Not only are these projects being pushed by private concessionaires on the pretext of solving the water shortage “crisis” in Metro Manila, they are also being railroaded by Duterte’s economic managers—sans the mandatory Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) of the affected indigenous peoples and the Environmental Compliance Certificate (ECC) from the DENR. Communities, especially the poor, face the triple burden of opposing extractivism and privatization, resisting corporate impunity and state complicity, and bearing the brunt of global warming and climate change. Unabashedly, state regulators and private concessionaires even use climate change as a convenient scapegoat to gloss over technocratic inefficiency and to elude accountability, as what happened in the Metro Manila water supply crisis.

A similarly crucial battle involves putting the issue of climate and environment at the forefront of the national agenda.

The dearth of consideration given to climate and environmental issues by both incumbent officials and candidates in the general election this year is indicative of the lack of appreciation of the urgency and public salience of climate change. Upon scrutiny of the electoral agenda and platforms of both the pro-administration ticket and the opposition coalition slate, no senatorial candidate has placed environmental protection as their number one priority agenda and rallying cry.

The upcoming Philippine midterm elections in May 2019 will be a referendum on the direction of the Duterte administration: a barometer of people’s continuing support at one end, or mounting dissatisfaction with Dutertismo on the other. At best, the outcomes could open up spaces for genuine peoples’ participation and representation in forwarding a well-grounded, inclusive, and strategic agenda on the environment, and contribute to the realization of systemic alternatives from below. At worst, the results would hasten the trend towards greater concentration of power and keep neoliberalism deeply embedded in the country’s social, political, and economic systems at the expense of the environment.

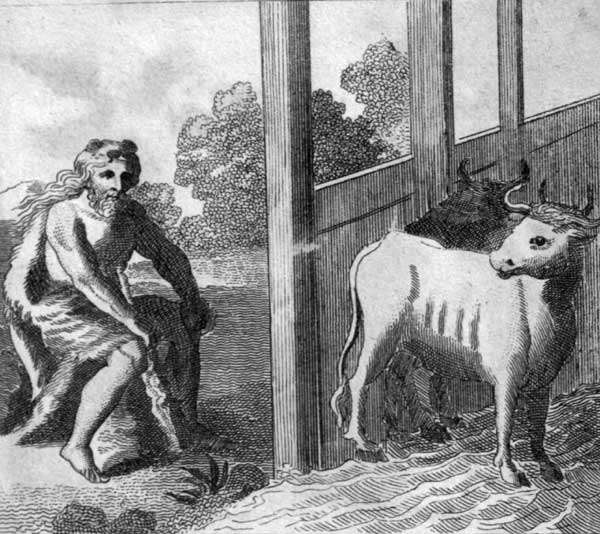

When Duterte labelled Boracay as a cesspool and ordered its closure, he forgot that an even bigger, far more putrid, corrupt, and festering political cesspool surrounds and props up the seat of power in Malacañang. The accumulated refuse of super-majoritarian, self-aggrandizing, and elite rule can be likened to the Augean stables: it would be a Herculean task to clean it up.

Hercules cleaning the Augean stables. Illustration from “The Twelve Labours of Hercules, Son of Jupiter & Alcmena”, 1808. Photo available from the Project Gutenburg site. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Augean_stables.jpg), marked as public domain.

Fulfilling the fifth of his twelve labours, Hercules had to completely muck out King Augeas’s stables—full of dung of a thousand cattle having not been cleaned in over 30 years—in a single day. The task seemed impossible at first until Hercules overcame it by making a breach in the foundations of the wall that surrounded the yard, diverting the courses of two rivers that flowed nearby through the stables, and finally washing out decades of filth

Duterte, a perceived “strongman”, is no Hercules to put our hopes and dreams on. We, the people, have the power in our own hands to cleanse the Augean stables.

In the coming mid-term elections, it is imperative to struggle, contest, and maximize use of its platforms—however limited the spaces, however bleak the possibilities, however Herculean the task may seem—for it is our duty to take action.

_________________

[i] “Laban-laban” can be translated as “struggle and fight” but can also mean “in conflict with one another.”

[ii] Bello, W. (2017 April 25). Burying Gina. Article published in Rappler: Thought Leaders. Retrieved from https://www.rappler.com/thought-leaders/167872-gina-lopez-mining-industry

[iii] Manahan, M. A. (2017 September 6). Laban-Bawi: Governing the Environment. Article published in the Focus Policy Review Vol. 6, No.1: Unpacking Dutertism: What to Make of President Duterte’s Year One. Quezon City, Philippines: Focus on the Global South. Retrieved from https://focusweb.org/laban-bawi-governing-the-environment/

[iv] Focus on the Global South. (2018 July 31). Duterte 2 Years on: Destructive, Divisive, and Despotic. Statement on the 3rd State of the Nation Address (SONA) 2018. Quezon City, Philippines. Retrieved from https://focusweb.org/duterte-2-years-on-destructive-divisive-and-despotic/

[v] Supreme Court Associate Justice Benjamin Caguioa’s dissenting opinion may be accessed at: http://sc.judiciary.gov.ph/pdf/web/viewer.html?file=/jurisprudence/2019/february2019/238467_caguioa.pdf

[vi] Supreme Court Associate Justice Marvic Leonen’s dissenting opinion may be accessed at: http://sc.judiciary.gov.ph/pdf/web/viewer.html?file=/jurisprudence/2019/february2019/238467_leonen.pdf

[vii] van der Kamp, D. (2017 July 17). Clean Air at what Cost? The Rise of “Blunt Force” Pollution Regulation in China. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Asian Studies – Annual Conference: Sheraton Centre Toronto Hotel, Toronto, Canada.

[viii] Palafox, F. (2019 January 24). Manila Bay Rehabilitation. Op-ed published in The Manila Times. Manila, Philippines. Retrieved from https://www.manilatimes.net/manila-bay-rehabilitation/501248/

[ix] PANGISDA-Pilipinas. (2019 February 7). Manila Bay Para sa Tao, NGOs, Join Small Fishers in Demanding Pro-People Rehabilitation. Press release at the public launch of Manila Bay Para sa Tao. Quezon City, Philippines.

[x] Pulse Asia Research, Inc. (2018 September 27). September 2018 Nationwide Survey on Urgent National Concerns and the Performance Ratings of the National Administration on Selected Issues. Quezon City, Philippines. Retrieved from http://www.pulseasia.ph/september-2018-nationwide-survey-on-urgent-national-concerns-and-the-performance-ratings-of-the-national-administration-on-selected-issues/

[xi] The World Risk Index is an instrument used to assess risk and vulnerability towards natural hazards.

[xii] Asian Development Bank and Postdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. (2017 July 14). A Region at Risk: The Human Dimensions of Climate Change in Asia and the Pacific. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank. Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/325251/region-risk-climate-change.pdf

[xiii] World Commission on Dams. (2000 November). Dams and Development: A New Framework for Decision-Making. The report of the World Commission on Dams. London, UK and Virginia, USA: Earthscan Publications Ltd. Retrieved from https://www.internationalrivers.org/sites/default/files/attached-files/world_commission_on_dams_final_report.pdf

![[IN PHOTOS] In Defense of Human Rights and Dignity Movement (iDEFEND) Mobilization on the fourth State of the Nation Address (SONA) of Ferdinand Marcos, Jr.](https://focusweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/1-150x150.jpg)