LAND RESEARCH ACTION NETWORK

“The issuing of land concessions and leases for tree plantations over large areas and for excessive periods has led to social and environmental problems and required both the resettlement of people and compulsory acquisition of the land which the people farm on. The people have lost their source of daily livelihood and lost their long-term rights to use the land”

This uncommonly frank public statement by a senior representative of the Lao government (1), as it began its review of past unsystematic decisions to allocate the country’s fertile lands for agricultural investment, could be equally said of the critical situation in rural areas of other countries of the South. About five years ago, reports started appearing in the media of a new wave of investment in agricultural lands all over the world. This was echoed by cries from communities whose lands, without warning, had been summarily cleared and fenced. Information began to emerge about deals often covering tens of thousand, even hundreds of thousands of hectares of farmland at a time, signed over by national and provincial governments under astonishingly lenient conditions, and extending corporate control over significant areas of land for decades to come (GRAIN, 2008, IFPRI, 2009, Cotula et al 2009, World Bank, 2010).

The vast scale and apparent speed with which the land is being taken over indicates that a new, global wave of land-grabbing is underway. While specific triggers may be different this time round, the underlying causes reflect similarities with the land grabs of the past (cf McMichael, 2010). Through the ages, productive lands, rich in water and natural resources, have always been the most valued assets of communities, societies and nations.

The current trend of investments is triggered by the interrelated crises in food, finance, energy and climate that have been spurred by decades of corporate driven globalization, neoliberal policy regimes, and natural resource exploitation. The convergence of these crises has prompted governments to consider urgently the need to secure their country’s future food and energy demands, and with limited stocks of productive land at home, the search has extended far afield. South Korea, for example, has made plans to restructure its agriculture sector, exploring new areas for production abroad as a more “cost-effective” measure than providing subsidies to its own farmers. It has been active in seeking out more land than its entire domestic area of arable land and in a long list of countries, including supporting a failed attempt to secure over a million hectares of land in Madagascar by the Daewoo corporation (GRAIN, 2008). Many of these global land grabbing deals are ostensibly struck in the name of development, food and water security, agricultural investment, and energy security. Several governments have used diplomatic and development assistance channels to open the way for teams of corporate representatives scouting for fertile lands and related deals, for example, the Philippines, Kuwait, Qatar, India, Vietnam and China.

However, large-scale investments in land are highly risk prone, primarily to the environments, local economies and communities in host countries. The lives of the investors are not on the line when ventures fail to yield projected financial returns, damage environments or capture precious natural resources. The highest risks are distributed to the large number of local farmers, forest users, fisherfolk, traders, and communities whose livelihoods may be completely destroyed by these projects.

Cases that have been highlighted include the expropriation of land belonging to entire villages of people with little or no monetary compensation and rarely any provision for alternative livelihoods – other than to take the penny of the company that threw them, unceremoniously, off their land. Offers of employment tend to materialize in much smaller numbers than originally promised, and, for various reasons, local people are being passed over in favour of a migrant work force who gradually flow in from precarious circumstances elsewhere. Studies find that the limited jobs on large-scale plantations favour the young, relegating older farmers to unemployment, depreciating their knowledge and skills, and where no alternative employment exists, placing them in long-term dependency on their children. The terms and conditions offered for industrial farm labour are often unclear and unmonitored, leaving many workers with no job security, scant protection against health hazards, irregular wage payments and no legal redress. Wages, after deductions, are found to be barely enough to bring home staple food, except where several workers are hired from one family, so even small price fluctuations have a direct impact on daily hunger. Such incomes cannot substitute for a lost productive farm, forest, wetland or rangeland on which a variety of foods and cash resources had been cultivated on a long term basis. (Schott, 2010; Laungaramsri et al, 2008)

Negative impacts of plantations are compounded where spaces of biodiversity – important food cupboards for families of the poor – are replaced with monocrop expanses, and treated with intensive, regular application of powerful pesticides and herbicides (Manahan, 2007, Mendonça, 2007). In many instances, families are forced to try to make a living by opening up new areas of forest and woodland for cultivation, often running the risk of conflicts with previously settled communities for access to limited resources. In other instances, families–and communities–are fractured when some members move to urban centres to work in the construction or hospitality industries, or to other rural areas as seasonal agricultural labour.

At the national level, land taken from control of local people for generations, presents a ticking time bomb of problems of future food insecurity, inequality and civil unrest for the next generation. The transformation of land use from nationally-oriented production to export-oriented production exposes countries to the risk of food price volatility influenced by commodity trading and consumption patterns in distant markets over which they have no control and little advance warning. Given existing land scarcity, most areas of productive land are already in use, and land acquisition for large scale investments is likely to result in landlessness. Studies so far have indicated that macro-economic returns from large land concession projects are inadequate, given that accompanying conditions such as tax, rent, social infrastructure, workers’ wages and welfare, etc. remain generally favourable to investors. Such projects also have large ecological footprints. In countries whose forest expanses are seen by government authorities as spare land available for commercial exploitation, large tracts of resource rich forests have been shorn from the land, damaging the micro-environment, exposing peat soils and releasing carbon into the atmosphere.

Promoting Land Privatization

Dire outcomes are reported not only by community-based studies. Two years ago, the World Bank, confirmed in the belief of potential benefits from private/corporate agricultural investments to ‘underperforming’ economies, embarked on a multi-country survey of existing investment projects to analyse ‘land grabbing’ from its own perspective. Its report, published in September, could not but acknowledge the “real dangers” of “uncompensated land loss by existing land users and land being given away well below its true social value”, having found that “many investments… failed to live up to expectations and, instead of generating sustainable benefits, contributed to asset loss and left local people worse off than they would have been without the investment… case studies confirm that, in many cases, benefits were lower than anticipated, or did not materialize at all” (World Bank 2010: 51).

What is not covered in the Bank report, however, is the role the Bank itself has played in driving global land deals and “resources restructuring”. Decades of neoliberal economic policies have laid the groundwork for welcoming transnational corporate investors to acquire land in agricultural producing nations. Export-oriented policies promoted by the Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Trade Organisation (WTO) have systematically discouraged small-scale production and food self-sufficiency, and encouraged food importation. The Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) dictated by the IMF and World Bank during the 1980s and 1990s helped to destroy African agriculture, especially, through the imposition of conditionalities that obliged the withdrawal of government controls and support mechanisms to provide farmers access to land, credit, insurance, inputs, and cooperative organization. “In other words”, as Dr. Walden Bello, academic, and leader of the Akbayan party in the Philippine Parliament, has put it, “the World Bank and IMF resident proconsuls reached into the very innards of the state’s involvement in the agricultural economy to rip it up”. Similar histories were repeated in Southeast Asia and parts of Latin America.

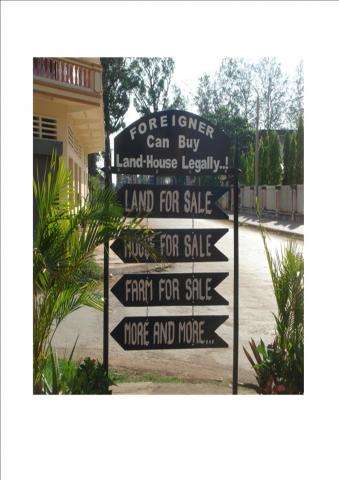

The Bank has also played an extremely strong role in promoting the development of land markets. Since the 1980s, it has offered loans for the overhaul of land tenure administration and transforming the nature of traditional, multi-layered, landholding relationships toward simplified individual private property regimes. Access to land through market mechanisms was pushed as a form of land reform – more easily palatable to entrenched national powers than the mandatory redistribution through agrarian reform sought by social movements (cf Rosset et al, 2006). In disastrous cases, titling programmes fuelled their own land grab, as wealthy and powerful individuals were best placed to gain land titles and freely transfer them for financial and speculative gain – leading to waves of dispossession of the poor, in both rural and urban areas.

More recently, the Bank’s role has focused efforts to improve ‘investment climates’ and ‘business enabling environments’. The International Financial Corporation (IFC) and the Foreign Investment Advisory Services (FIAS), both part of the World Bank Group are engaged in providing advisory services and technical assistance on investments in land. Developing countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America have been encouraged to create investment promotion agencies, “one-stop shops” for inward investment, and rewrite national laws in favour of liberalization. A great many of the new investment agencies set up in the client countries have eagerly ushered in large-scale foreign investment in land involving the transfer of massive areas of land (Daniel and Mittal, 2010).

The cultural traditions that emphasize collective land/resource management for long-term survival of a community or group have also been undermined by this systematic bias towards privatization. Previously held under common property tenure regimes of one form or another, natural resources – of tremendous value to local communities for foraging, gathering, fishing, trapping, grazing and regenerating biodiversity and soil fertility – have been parceled out. Under individual tenure, rangelands became unproductive, woodland resources were unevenly distributed, and preventing ecosystem damage was no longer a shared value and imperative. Plots were subsequently sold, frequently to buyers interested only in accumulation, with no long-term stake in the health of the resources or the community.

The “commons” are still regularly neglected in policy decisions. Where they have not been individually appropriated, they are termed “state property” by default. Of little direct value to remote public administrations – they may not contribute to GDP or government coffers – “common lands” can be too easily labelled “idle”, “marginal” and “unproductive”, regardless of the wealth of biodiversity and foodstuffs to be found there. This political revision serves to justify their transformation towards “economically productive,” industrial, chemical-intensive, monoculture plantations, large-scale commercial aquaculture, extractive industries and exclusive tourism enclaves.

National governments have been criticised for failing to prioritize the welfare and human rights of their citizens and migrant communities in these land deals, which have been concluded without transparency to local community groups and the public, and sometimes hidden also from the eyes of donor “partners” (cf World Bank, 2010). The murky nature of the investments have been remarked on by a number of observers (IFPRI, 2009, Liversage, 2010), raising the suspicion that corruption is at the core of such decisions.

International Initiatives for Land and Resource Governance

The lack of transparency and near absence of effective remedies to address the economic, social, environmental and political problems resulting from these recent deals have unleashed widespread national and international reactions against land acquisitions by state and corporate investors. In a bid to prevent the worst excesses of large scale investments and pre-empt public backlash against foreign driven land grabs, international multilateral organizations have begun drafting international frameworks to set good governance standards for land and natural resource tenure, and for agricultural investments by private corporations

The International Conference on Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ICARRD) organized by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in 2006, reaffirmed the fundamental importance of wider, secure and sustainable access to land, water and other natural resources, and of agrarian reform for the eradication of hunger and poverty. Economic, social and cultural rights, in particular of women, marginalized and vulnerable groups were recognized to be essential considerations in dealing with land and natural resources issues.

This gave impetus to the FAO’s Committee for World Food Security (CFS) to launch an initiative to draft Voluntary Guidelines for Good Governance in Land and Natural Resource Tenure, aimed at providing practical guidance on responsible resource governance as a means of responding to global challenges, particularly the new wave of global land grabbing. A broad agreement is being sought among governments, civil society, constituency groups and international organizations, to be approved by FAO member nations and other interested parties. Specific content is currently being formulated in an international consultative process, which can be followed online.(2) Regional and constituency-specific consultation meetings have been held, and further participation of civil society, particularly groups most affected by landlessness and tenure insecurity, is being engaged adopting the FAO’s principles of engagement (3). The draft guidelines are scheduled to be submitted for approval at the next session of the CFS in 2011.

While it is still unclear what the outcome of this process will be, and how much progress it will represent, many social movements and civil society organizations (CSOs) see the preparation of these guidelines as an opportunity to establish a mandatory framework for public regulation of investments in land, forests, agriculture, coastal and marine zones. It is not expected that this framework will establish new legally binding obligations, but provide guidance on how to ground national and sub-national policies in existing international human rights obligations.

In the meantime, other institutions have called for ‘codes of conduct’ or principles to reign in the ‘irresponsible’ behaviour of agri-businesses engaged in the rapidly increasing investments in land. The World Bank, International Food and Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), have formulated and are promoting “Principles for Responsible Agricultural Investment that Respects Rights, Livelihoods and Resources (RAI) so that developing economies can benefit from potential “win-win” opportunities that private agricultural investments supposedly offer. These include among others: recognising existing land rights, proper consultations with local peoples, ensuring economically viable projects, and urging investors to respect the rule of law and reflect industry best practices. The FAO, also involved in this effort, emphasizes that “investments could be good news if the objectives of land purchasers are reconciled with the investment needs of developing countries” (FAO, 2009).

A set of seven principles were published in January 2010 by these institutions, as a contribution to “an ongoing international dialogue”. While the principles are written to be reasonable, rational, and persuasive, they are problematic in a number of key issues. The guidelines are written on the premise that the transfer of land rights is desirable for stimulating agro-enterprise development, and that this transfer can be effected in a ‘responsible’ way. Social movements and CSOs however are concerned that the principles represent a move to legitimize the long-term corporate, both foreign and domestic, co¬ntrol of rural peoples’ land (4), discounting future livelihood and environmental security in favour of present day monetary gains.

In advance of the CFS meeting in October 2010, an analysis was presented by the Global Campaign for Agrarian Reform (GCAR) – which includes La Via Campesina, FIAN International, Focus on the Global South and the Social Network for Justice and Human Rights (Rede Social) – which addressed each of the RAI principles (LRAN, 2010). GCAR points out that the RAI is not linked to the international human rights framework: the RAI does not recognise the rights of small scale, local food producers to secure productive resources, to produce and be food self sufficient through their own means, to safe and healthy environments, and to the principle of Free Prior Informed Consent. Instead, the RAI is primarily concerned with facilitating enabling conditions for a “stable and efficient investment climate” for corporations, regardless of the production model (5).

Another proposal for halting the rampant expansion of investment into forested lands is also of relevance here. The REDD initiative (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) initiated under the UNFCCC process was born of the idea that, in ‘cash-strapped’ economies, unless forests provide economic rents, it will be all but impossible to protect them in the face of lucrative large-scale proposals for extracting forest resources and monoculture crop development. The initiative aims to ostensibly halt the deforestation that contributes to GHG emissions and global warming. However, peasant and indigenous people’s networks and CSOs have raised alarms that loopholes in the methodologies and conceptual bases of REDD proposals will allow further commercial exploitation of so-called “degraded” forests through schemes for plantation forestry, and are creating new motives for the exclusion of forest peoples from their territories. Several other concerns have been raised in relation to this initiative, not the least of which is the link with carbon trading markets that partially relinquish responsibilities to reduce emissions elsewhere. The REDD debates will continue at the upcoming Conference of the Parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 16) in Cancun.

Conclusion

While there may be new actors on the land grabbing scene, the processes and impacts of land grabbing today are consistent with past experiences. The conditions spurring and enabling the current spate of land grabbing were laid down several years—even decades–ago. On World Bank-IMF advice, numerous natural resource rich developing countries adopted the open door approach to foreign investment and trade, restructuring their domestic agriculture and industry sectors, and rendering their economies vulnerable to international capital. In Northern and oil-rich states, meanwhile, the convergence of the global crises of climate, food, finance and energy propelled governments, financiers, and agribusiness developers towards a new, frenzied, search for the physical security of land, water and productive resources that create wealth. Real estate developers, banks, corporate financiers, insurance and investment companies, and mutual and pension funds joined agribusiness corporations and wealthy governments in seeking out and staking investment possibilities with assured returns. The lands and resources of the South stood exposed, and Southern governments were keen, in many cases, to receive this heightened commercial interest in their agricultural land and infrastructure.

Over the past several decades, support for agricultural development has been directed most generously to the large scale production sector, often dominated by agribusiness and agrifood corporations. Arguments that this sector is best placed to feed the growing population are belied by the displacement of local food producing communities, and the shift in cropping priorities towards fuels, animal feed and industrial crops at the behest of international market demands. FAO has estimated that numbers of the hungry have swelled to around one billion because of the recent food price crisis. The surge in land grabs will undoubtedly increase these numbers, even if many of the grabbed lands are used to grow food crops for humans and animals in distant countries.

A positive outcome of the multiple crises, however, is a renewed interest among peoples, academics, entrepreneurs, scientists and even policy makers in alternative models of production, consumption, and using energy and resources. In recent years, the national and local advantages and benefits of maintaining a vibrant and viable small scale production sector have begun to be more clearly recognised at national and international levels. The high-profile International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD, 2009), highlighted the importance of this sector and recognised the multifunctionality of traditional production practices, which confer value for society (by reducing vulnerability, improving access to food, livelihoods and health, increasing equity, etc.) as well as for the environment and the planet.

Defending their lives, lands, territories and collective rights to food and water are everyday struggles of many rural peoples. Community-led initiatives supported by networks and social movements remain important means for affected peoples to gain and retain access and control over resources. In this process, communities themselves can set the terms of resource governance, including the recognition of their rights to self-determination and to decide how to govern, manage and care for their ecosystems in democratic, equitable and sustainable ways. Measures to redistribute, protect and nurture land and water resources, including comprehensive agrarian reform programs, can pave the way for a new framework of governance of land and the natural commons, which puts local communities in control of their own territories and livelihoods.

Acknowledgement

The lead writers for this collaborative piece by the Land Research Action Network were Shalmali Guttal,Rebeca Leonard and MaryAnn Manahan.