Shalmali Guttal, Focus on the Global South. April 2011*

Climate change and the climate crisis generally refer to alterations to the Earth’s climate systems that result from human activities (also called anthropogenic climate change). The burning of fossil fuels, extraction and exploitation of natural resources, production-consumption of energy and industrial goods, and high consumption lifestyles are all high emitters of Greenhouse Gases (GHGs), which are responsible in great part for the relentless warming of the earth. Climate change has already led to disruptions in seasonal weather and precipitation patterns, the melting of glaciers and ice caps, changes in hydrological cycles and an increase in extreme weather events, with serious consequences for ecosystems, agricultural production, food and water security, and the lives and livelihoods of rural and urban poor communities throughout the world. Low-lying coastal areas are already facing submergence from rising sea levels, and nine out of every ten natural disasters today are estimated to be climate related.

Land and water are central elements in the climate crisis. The activities that cause anthropogenic climate change are equally responsible for depleting freshwater sources, degrading soil, lands and forests, and destroying diverse ecosystems. Industrialization and economic growth depend immensely on the exploitation of land, water and other natural resources; their capture to serve energy production, transportation, mining, industry, agriculture, technology, tourism, recreation, urban expansion and modern lifestyles, continues unabated in every region of the world. The world’s natural forests, savannahs and wetlands have long helped maintain the global carbon cycle in balance but their conversion to other uses has greatly diminished this crucial ecosystem service. Studies, including by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), show that land use and land use changes are responsible for over 30 % of GHG emissions.

Plants, animal species and marine life are threatened or disappearing at an unprecedented pace due to the combined effects of global warming and industrial exploitation. Life at large is endangered by the decreasing availability of fresh water resources. IPCC assessments indicate that from 2050 onwards, ‘water stress’ will more than double. Increased precipitation intensity and variability will likely increase the risks of both, flooding and drought in many areas and negatively affect groundwater recharge, thus reducing underground water stocks. Changes in water quantity and quality are expected to result in decreased food availability and increased vulnerability of poor rural communities, especially in the arid and semi-arid tropics, and Asian and African mega-deltas.

The impacts of climate change will go beyond the physical. Consistently changing, unpredictable weather challenges local knowledge and community resilience, which have been the basis of good agricultural and eco-system management, and which have been built over generations through autonomous adaptation by farmers and fishers to changing environmental conditions. The deepening climate crisis, however, will demand more drastic adaptation measures. “Planned adaptation” – deliberate measures aimed at creating the capacity to cope with climate change impacts – will entail changes in land use, tillage systems, water supply and irrigation, crop varieties, agricultural technologies, and the management of forests and other eco-systems to adjust to new climatic conditions. Some of these measures are likely to render rural communities more vulnerable and dependent on external inputs and techniques, and result in the loss of precious local knowledge about food, medicinal plants, soil, water and coastal management, agricultural production, forest and biodiversity protection, etc. For example, the Alliance for Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) aims to build resilience in African agriculture through the systematic transformations of native seeds, cropping systems, agricultural knowledge and practices, natural resource management, credit and marketing, etc.

Land and ecosystems under threat

Today, about 75 percent of the world’s poor live in rural areas in developing countries and practice smallhold family agriculture, artisanal fisheries and/or pastoralism. Their daily food, fuel and other household needs are met primarily through localized production and foraging activities– often by women–in family owned plots, common grazing lands, woods, forests, streams, rivers and lakes. These production/foraging practices and the eco-systems that sustain them are increasingly under threat from changing weather and precipitation patterns because of climate change, as well from intensifying demand for farmlands, forests and water sources among state and private investors, corporations, traders, brokers and speculators.

In tropical and semi-tropical regions, climate change will likely lead to a serious decline in agricultural yields, accelerate forest, farmland and coastline degradation, increase desertification and displace millions of rural peoples from traditional occupations. As it is, terrestrial, freshwater and marine eco-systems are already under severe pressure from extractive industry, tourism, industrial agriculture and commercial fisheries. These pressures are being compounded by the global resurgence in land grabbing.

The latest ongoing rush to acquire land –global land grabbing–is driven largely by four factors: food price volatility and unreliable markets; the energy crisis and interest in agroenergy/biofuels; the global financial crisis; and a new market for carbon trading (Borras, Scoones and Hughes, 2011). The global food, finance and climate crises have transformed agricultural lands and production infrastructure into valuable strategic assets. Wealthy countries unable to meet their food needs through domestic production (for example, Japan, South Korea, China, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Libya and Saudi Arabia) are acquiring massive tracts of farmland (and the water sources that lie in them) on long leases in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Agribusiness and finance corporations (for example, Morgan Stanley, AIG, Deutsche Bank, Goldman Sachs, Renaissance Capital and Landkom) have also been acquiring lands (and water sources) in the South to secure returns on future investments. Even when states acquire farmlands, they outsource actual production to agribusiness/agri-food corporations which tend to invest in crops and trees that fetch maximum profits: soybean, wheat, corn, cassava, sugar cane, jatropha, rubber and other bio-energy crops, grown on large expanses through industrial modes of production that are energy and fossil-fuels intensive.

Such agricultural investments have extremely high carbon footprints. Smallhold diverse farms, forests, open pastures and other commons are converted to large industrial agriculture monocultures that consume vast amounts of agro-chemicals, energy and fuel for production, processing, storage and transportation of inputs and finished goods. According to the International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD), the highest GHG emissions from agriculture are associated with industrial agriculture and intensive monocultures, which include medium to large scale, chemical-intensive production of cash, food and agroenergy crops, plantations and industrial livestock production (IAASTD, 2009). FAO estimates that including commercial feed crop cultivation, transportation of feed-crop and animal products, enteric fermentation, and CH4 and N2O emissions from manure, the industrial livestock sector alone is responsible for 18 percent of GHG emissions (FAO, 2006).

Industrial agriculture and monocultures are not only resource and energy intensive, but also have complex and multi-dimensional impacts on forests, ecosystems, watersheds, food security and livelihoods. The intensive use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides destroy biodiversity, pollute soils, rivers, waterways, subterranean water sources and springs, and gravely affect the health of communities and eco-systems. When wild food sources are destroyed, rivers and wells poisoned, and fish and small marine animals disappear, rural communities are left with practically no food and water sources. Local communities experience adverse impacts in multiple ways: they are unable to meet their food and household needs through their own production and foraging; they have to rely on services set up by new landlords; they must either work as wage labour on the new plantations or as contract farmers to the new agro-enterprises, and; they lose all agency over the management of lands and ecosystems.

Agricultural land occupies about 40-50 percent of the world’s total land surface, and accounts for 60-80 percent of global nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions and 50-55 percent of methane (CH4) emissions. Studies show that globally: agriculture accounts for about 13.5 percent of GHG emissions (though counting transportation, processing and distribution, the figure is likely to be much higher); land use change and forestry represent about 17.4 percent and deforestation is responsible for 25-30 percent of GHG emissions.

Agricultural soils are both sources and sinks for carbon. In tropical rain-forest regions, global trade and the intensification of market economies encourage forest destruction to make way for industrial croplands and pastures for the cattle industry. Industrial agriculture and monocultures destroy natural processes needed to store carbon in soil organic matter and replace them by chemical processes from fertilizers and pesticides, the production of which consume large amounts of fossil fuels. They also destroy important landscape features such as live fences, woodlots, catchment areas, hedge-rows, patches of natural forests and other natural habitats that provide crucial ecosystem services such as recharging aquifers and watersheds, retaining soil nutrients and sequestering carbon.

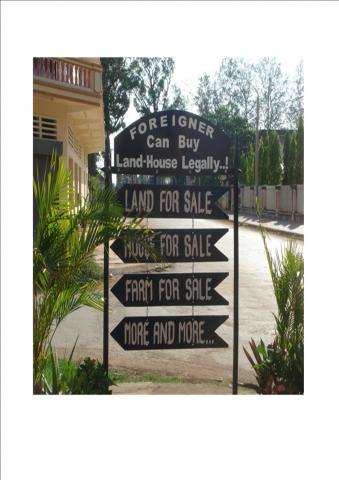

The conversion of forests and diverse, smallhold farms to industrial agriculture have far reaching environmental, social and economic effects, including acceleration of climate change. Conversions exacerbate inequality of access to land and natural resources among communities and between men and women, especially in the case of bio-energy and other high value cash crops. As forests, grasslands and small farmlands are expropriated for industrial farms and plantations, local communities are squeezed onto smaller and less fertile parcels of land and compelled to rely on a smaller resource base for food and income. Fresh water reserves are monopolized by industrial agriculture, creating and exacerbating water scarcity. This has sparked conflicts over water, forest products and common pool resources among local populations, who are pushed to compete for already dwindling resources. Particularly affected are the rights of indigenous peoples to control, use, administer and preserve ancestral territories. Increasing and aggressive land purchases by those with money have driven up land prices and created booming land markets in which impoverished smallhold producers become easy prey to land speculators and middle-men.

Land/forest conversions also weaken community resilience to withstand weather shocks and natural disasters. Areas without natural forests and landscapes are more susceptible to floods, mudslides, storms, soil erosion, aridity and pests, against which local populations have few defenses. The depletion of natural resources undermines women’s knowledge about traditional uses of wild plants as food, fodder and medicine and increases their work-load in meeting the family’s food and health needs.

Cashing in on climate

Climate change is proving to be fertile ground for agribusiness, agrochemical and energy corporations, financiers, traders and other investors to concentrate new assets and reap huge profits. With support from some governments and international agencies, business lobby groups have promoted the use of market mechanisms such as carbon/emissions trading and Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) through the Kyoto Protocol as ways to “mitigate” climate change. These schemes enable Northern governments and their corporations (responsible for the bulk of GHGs) to buy “certified emission rights” from Southern countries at lower levels of industrialization, finance carbon sinks and “sustainable development” in the South, and avoid cutting emissions in the North. Carbon sinks include industrial tree plantations (in the guise of afforestation and reforestation) which release more pollutants into the atmosphere than sequester carbon.

A variety of agricultural activities can be subsidised through carbon trading and CDM, all of which influence how lands and forests are used and managed. Of particular concern are forest management (including commercial logging), afforestation, reforestation and re-vegetation (including large scale tree plantations and virtually any type of crop cover), crop management (including industrial agriculture techniques and GM crops), soil carbon management through technologies such as no-till (which entails the application of large amounts of herbicides and agro-chemicals to avoid ploughing the soil, often in GM monocultures) and agroenergy expansion. Current trends indicate that small scale biodiverse and integrated farming, fishing and livestock raising—which have a high potential for slowing down climate change and regenerating biodiversity—are not likely to benefit from CDM or other market based schemes. Financing will go primarily to large scale, industrial mono-cultures, including agroenergy crops and agrofuel production, which will continue deforestation, ecosystem destruction, environmental pollution, and the displacement of indigenous and other local communities.

The World Bank has aggressively assumed the lead in ‘carbon finance’ schemes through, among others, the Prototype Carbon Fund, Community Development Carbon Funds, BioCarbon Fund, Umbrella Carbon Facility and Forest Carbon Partnership Facility. Many of these programmes claim to reduce GHG emissions in developing countries from deforestation by selling forest carbon credits in the international emissions market. In November 2010, the World Bank signed an agreement with the Kenya Agricultural Carbon Project to purchase soil carbon credits through its BioCarbon Fund from Kenyan farmers .

Significant among forest carbon initiatives is the Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD), which aims ostensibly to reward governments and forest owners in developing countries for protecting forests instead of cutting them down, thus reducing GHG emissions. The World Bank is actively supporting REDD, as are several international environmental conservation agencies and private carbon trading companies. REDD is wracked with uncertainties and loopholes, starting from its very name. The UN definition of forests does not distinguish between natural forests and plantations, leaving the door open for private investors and governments to convert natural forests to tree plantations and still get paid for it. Much of what is labelled as “degraded forest” in official parlance are woodlots and fallows that rural and forest-based communities use to forage for food, fodder, fuel and medicinal plants.

A particularly contentious issue is tenure: who owns the forests, and who should be rewarded for protecting and not cutting forests? REDD includes “conservation of forest carbon stocks,” “sustainable management of forests” and “enhancement of forest carbon stocks.” These allow for conservation projects that can evict local communities from forest areas, allow logging in particular forest sections, and the conversion of natural forest cover (even if sparse) to industrial tree plantations. Governments generally claim ownership and sovereignty over all resources within their territories and will strike deals wherever they get maximum gains, whether in REDD programmes, or with logging, energy, mining or agribusiness companies. Claims of rural communities and indigenous peoples to use and make decisions about the forests that they have long stewarded are not recognized by governments or the environmental conservation industry.

REDD does not uphold crucial human rights instruments such as the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the concept of Free Prior Informed Consent. Indigenous Peoples and other rural communities fear that REDD and associated initiatives will further advance land grabbing and provide incentives to governments and large landholders to apply a “you-pay-or-I-cut” approach to every hectare of forest land that they succeed in wresting from indigenous peoples and landless farmers. In both CDM and REDD projects, lands, watersheds and forests are valued more in monetary terms rather than in terms of the varieties of life that that they sustain.

To date, no market mechanism has reduced GHG emissions or halted deforestation. Instead, land, soils and forests are being economically manipulated to allow investors to profit from the climate crisis. Unfortunately, recognising climate as ‘atmospheric commons’ has enabled their capture by corporate polluters and financial traders. Wealthy societies, corporations and investors gain access to abundant cheap “carbon credits” that help them to avoid the responsibility of cutting their own emissions and adopting ecologically sustainable lifestyles. Trading forest and soil carbon will not reduce global warming; on the contrary, it will create greater incentives and opportunities for the commodification of forests in international carbon markets. Bubbles and instability in these market can render precious natural resources vulnerable to market risks, with falling prices creating perverse incentives to withdraw forest protection.

Agrofuels: a dangerous panacea

Agrofuels are being widely promoted by governments and agribusinesses as environmentally- friendly and clean alternatives to fossil fuels. Experience to date shows, however, that agrofuel production has resulted in shortages of food stocks, increased food prices and mass evictions of rural peoples worldwide (Biofuelswatch et al, 2007; LRAN et al, 2007; The Gaia Foundation et al, 2008). Agrofuels production expand the industrial agricultural frontier at the expense of forests and native ecosystems, pollute water, degrade soils and dispossess rural peoples from their common pool resources. Most commercial production of agrofuel feedstocks–for example, corn, sugar cane, oil palm, soybean and jatropha—is through industrial monocultures on large tracts of public or state lands (including forests and grasslands) that provide livelihoods to millions of smallhold cultivators, forest users and pastoralists through unofficial, customary, use rights. These arrangements are broken down as governments fence public lands and hand them over as long lease concessions to corporations for agrofuel production.

The agrofuels craze is spurred by financial incentives provided to the private sector by governments that seek to maintain high consumption lifestyles in their countries despite the costs to communities and environments elsewhere. The United States, European Union and other OECD countries have established mandatory targets, policies and financial supports to encourage first and second generation agro-fuel production. They are also investing heavily in research and experimentation, including the development and testing of genetically modified crops and trees.

As wealthy nations meet their “clean” energy targets, precious farmlands are diverted from food to fuel production and millions of smallhold farmers, pastoralists and indigenous peoples are pushed off the lands and forests that they depend on for survival. Governments and corporations may argue that many of the lands converted to agro-fuel plantations are “wastelands” or “marginal lands” that need to be put to productive use. In actuality, however, all lands claimed by corporate acquisition are already in use by local communities in some form or other, and many are likely to have been under communal or traditional customary use for generations. Women farmers, who are the world’s main food producers, are the most prone to work on so called “marginal lands” because of traditional-historical gender discrimination and more easily divested of their rights to land than men.

The conversion of arable land and forests (degraded or not) to monocultures for commercial agrofuel production has serious negative impacts on food security, especially for people who already spend over half their incomes on food. The global food crisis is at least in part due to the heady rush towards agrofuel and animal feed production. Farmers displaced by agrofuel plantations are practically robbed of the abilities to feed themselves and their communities. Ironically, converting native ecosystems into farms for agrofuels will increase global warming rather than mitigate it. The carbon released by converting rainforests, peatlands, savannas or grasslands outweighs the “carbon savings” from agro-fuels. For example, conversions for corn or sugarcane (ethanol), or palms or soybeans (biodiesel) release 17 to 420 times more carbon than the annual savings from replacing fossil fuels. Scientific analyses also show that not all agrofuels are “clean” or “efficient” energy sources. Many ethanol agrofuels are proving to be far less “efficient” than other fuels for every unit of energy produced. The production of agrofuel crops (particularly for ethanol) and the fuel itself are chemical, water and even fossil fuel intensive, and result in land, soil and water contamination, and destruction of agricultural and natural biodiversity.

Defend land, nature and dignity

Official debates about climate change and hunger tend to favour technological and market-based solutions instead of addressing socio-political structural issues such as landlessness, highly concentrated ownership of agricultural lands and water, and industrial modes of production and consumption which are at the core of the crises. The climate and food crises have been transformed into opportunities for corporate profits, and land, water and other natural resources are being monetized, reassessed and exploited as never before.

The returns from industrial agriculture provide high, short-term returns for corporations, rich investors and wealthy classes, in contrast with agro-ecological peasant agriculture, where the returns largely go to local communities, society at large and future generations. Smallhold producers on family farms produce over two-thirds of the staple foods in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Small farms, especially those based on traditional polycultures, are far more productive than large farms in terms of total outputs, which include grains, fibres, fruits, vegetables, fodder, and animal products, all grown in the same fields or gardens. They tend to use land, water, biodiversity, energy and other agricultural resources far more efficiently than industrial agriculture and monocultures, are far less polluting, and far more climate-friendly. They provide vital ecosystem services and have great potential to sequester carbon in above-ground and soil biomass. In terms of converting the earth’s natural wealth into “outputs,” society gains much more from smallhold producers than from agribusiness and corporate agrochemical operations.

At the same time, the diversified cropping practices of traditional agro-ecosystems make them less vulnerable to massive losses during natural disasters. The traditional technologies and knowledge of smallhold producers, pastoralists, fishers and indigenous communities are a veritable storehouse of lessons in adaptive capacity and resilience to weather and climate change. These capacities and knowledge will be greatly diminished, if not altogether lost, if land conversions continue at the current pace.

Indigenous cultures have long upheld the importance of living in harmony with nature and many have warned us about the ecological limits of economic growth. They have developed sophisticated systems of plant and animal breeding, soil and water management, eco-system restoration and building resilience to natural disasters and environmental variability. On the December 8, 2010, Bolivia became the first nation state to enshrine this wisdom into law through landmark legislation that will give nature legal rights, more specifically, the rights to life and regeneration, biodiversity, water, clean air, balance, and restoration. In the same month, Bolivia also brought two resolutions—the Harmony with Nature and World Peoples Conference on Indigenous Peoples—before the General Assembly (GA) of the United Nations. The GA approved by consensus the two resolutions, which made reference to the World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth that took place early this year in Cochabamba, Bolivia.

Corporate control over land, forests and water sources must be urgently dismantled, and states and societies must recognize the fundamental rights of local populations to govern and steward the commons. Land, forests and water must be protected as common societal wealth, and security of resource tenure for smallhold farmers, fishers, pastoralists and indigenous communities should be ensured through comprehensive agrarian reform. Public policies and resources must be redirected towards supporting land-use and agricultural practices that cool the planet, nurture biodiversity and save energy. These will check global warming, achieve food sovereignty, reduce distress out-migration from rural to urban areas and allow us to leave a healthy planet for future generations.

* This article is drawn from an earlier paper titled Climate Crises: Defending the Land by Shalmali Guttal and Sofia Monsalve, that appeared in Development, 2011, 54(1)

** Download attachment with references