On 6 November 2021, more than 200 thousand people were on the streets of Glasgow united for one reason, protect the planet and protest against the bla bla bla and empty promises that are being made by the world leaders. Credit: Jessica Kleczka @stopcambo (https://twitter.com/StopCambo).

By Joseph Purugganan

COP 26 is over and the outcome of the latest negotiations aimed at addressing runaway climate change, the so-called Glasgow Pact is out. The Conference has been widely viewed as a failure even against its own stated goals of scaling up commitments to keep temperature rise below 1.5 C by accelerating the phase out of coal among other actions, and delivering on the earlier commitment to mobilize much needed climate finance.

In 2015, at the conclusion of COP 21, and the forging of the Paris Agreement, two narratives were at play– the narrative inside had a celebratory tone highlighting the landmark agreement forged among States. The other narrative, one amplified on the streets of Paris and across the globe, had a more sober tone and chose to highlight the continuing struggle for climate justice and for real solutions in the wake of a global deal forged inside the UNFCCC that lacked the urgency and resolve to address the climate crisis.

This time around, the level of disappointment over the outcomes, and the view in fact that States through these negotiations are failing us has become more widely accepted. While in the end, 200 countries supported the agreement, the vagueness, and lack of ambition of the entire deal, and not just the last minute drama over the phase down or phase out of coal, further underscores the greater challenge ahead.

In this article, we look back at the key areas in these climate negotiations, the promises made six years ago in Paris and the context leading up to the Glasgow Climate Pact.

Emissions Reduction

The Promise:

Long term goal to limit global temperature rise “to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels” and an aspirational line ” to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels.

What has happened:

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released in August 2021 the first part of the Sixth Assessment Report, laying down the latest scientific findings on climate change.Two key messages stand out from the AR6 report: (1) Recent changes in the climate are widespread, rapid and intensifying, and unprecedented in a thousand years; and (2) Unless there are immediate, rapid, and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius will be beyond reach.

The UNEP’s Emission Gap report 2020 finds that, “despite a brief dip in carbon dioxide emissions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the world is still heading for a temperature rise in excess of 3°C this century – far beyond the Paris Agreement goals of limiting global warming to well below 2°C and pursuing 1.5°C.”

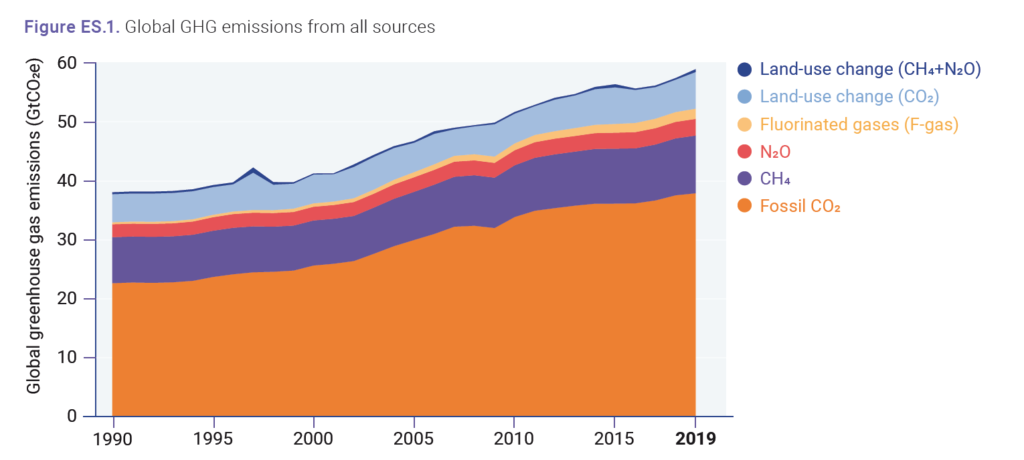

Source: UNEP Global Emissions Report 2020. https://www.unep.org/emissions-gap-report-2020

According to UNEP, “global emissions continued to grow for the third consecutive year in 2019, reaching a record high of 52.4 giga tonnes excluding land use change emissions and 59.1 giga tonnes when including LUC.”

“Fossil carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels and carbonates dominate total emissions including LUC (65 percent) and consequently the growth in GHG emissions, the UNEP reported.

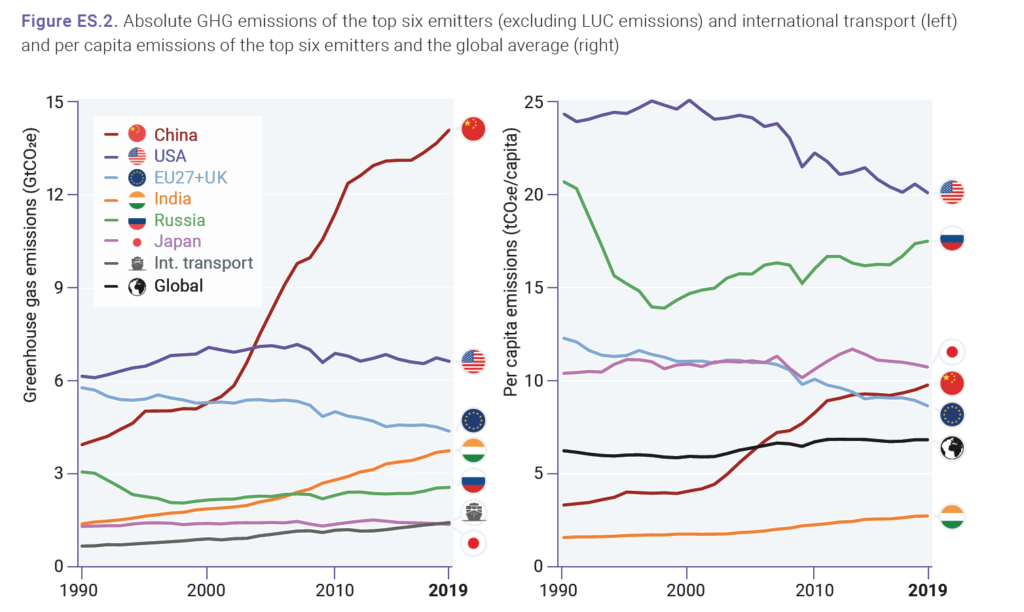

The top emitters in terms of absolute GHG emissions continue to be China, the United States, the EU+UK, Russia, India, and Japan. In terms of per capita emissions, the US continues to be on top of the list followed by Russia, Japan, China and the EU.

Nationally Determined Contributions

One major criticism with the Paris agreement was how it institutionalized the shift away from globally determined targets to country level pledges through so-called Nationally Determined Contributions or NDCs.

The latest UNFCCC assessment of existing NDCs, show how these pledges fall short of the target set under the Paris Agreement. The report finds that taking into account the implementation of all the latest (as of July 2021) NDCs, “the total global GHG emissions level in 2030, is expected to be 16.3 percent above the 2010 level.” Furthermore, the report pointed out that in order to be”consistent with the global emissions pathway with no or limited overshoot of the 1.5 degree goal, global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions need to decline by about 45 percent from the 2010 level by 2030. For limiting global warming to 2 0C, CO2 emissions need to decrease by about 25 percent from the 2010 level by 2030.”

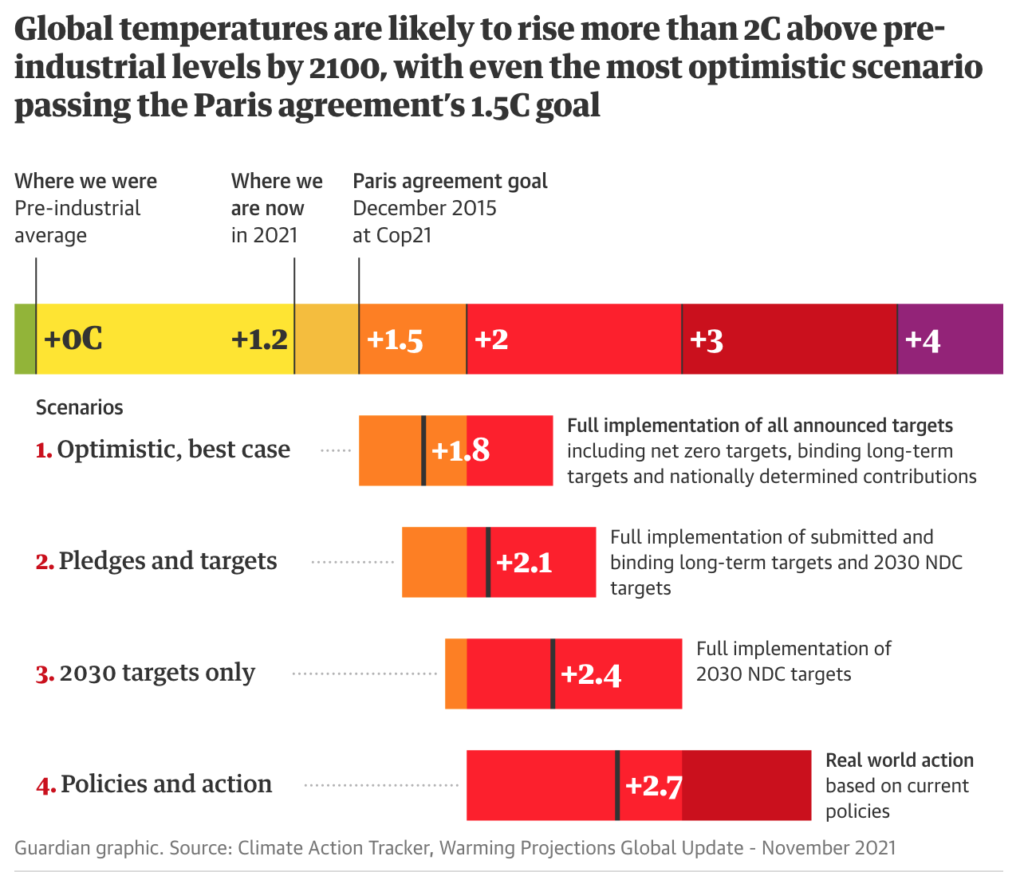

Climate Action Tracker (CAT), a coalition monitoring and analyzing the climate numbers, spelled out clearly the implications of the inadequate pledges. “ Temperature rises will top 2.4C by the end of this century, based on the short-term goals countries have set out.” As a report from the Guardian newspaper headlines : ”The world is on track for disastrous levels of global heating far in excess of the limits in the Paris climate agreement, despite a flurry of carbon-cutting pledges from governments at the UN COP26 summit.”

Source: The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/nov/09/cop26-sets-course-for-disastrous-heating-of-more-than-24c-says-key-report

Climate Finance

The Promise:

There was a reference in the agreement to the target of a minimum US$100 billion per year with a promise to scale up after periodic reviews. We pointed out as early as 2015 the weak language in the agreement that limited the commitment of States to “mobilize and facilitate the mobilization” of climate finance. There was a slight improvement in the final text when it came to the issue of differentiation as the phrase ‘shared effort’ was replaced with a more general ‘global effort’ and the onus of providing climate finance is more clearly placed on developed countries.

Even then the minimum pledge was deemed insufficient already. A news report from the New Internationalist cited figures from the International Energy Agency, on the required amount of $1,000 billion per year by 2020 to move towards the transformation to a fossil-free world.

“Around two-thirds of this – so $670 billion – will need to be spent in developing nations, hence the need for a significant transfer of finance from North to South,” The report adds “this (commitment on climate finance) is inadequate and mean, especially given that governments spend an estimated $5,300 billion per year on direct and indirect subsidies to fossil fuels.”

Where we are now:

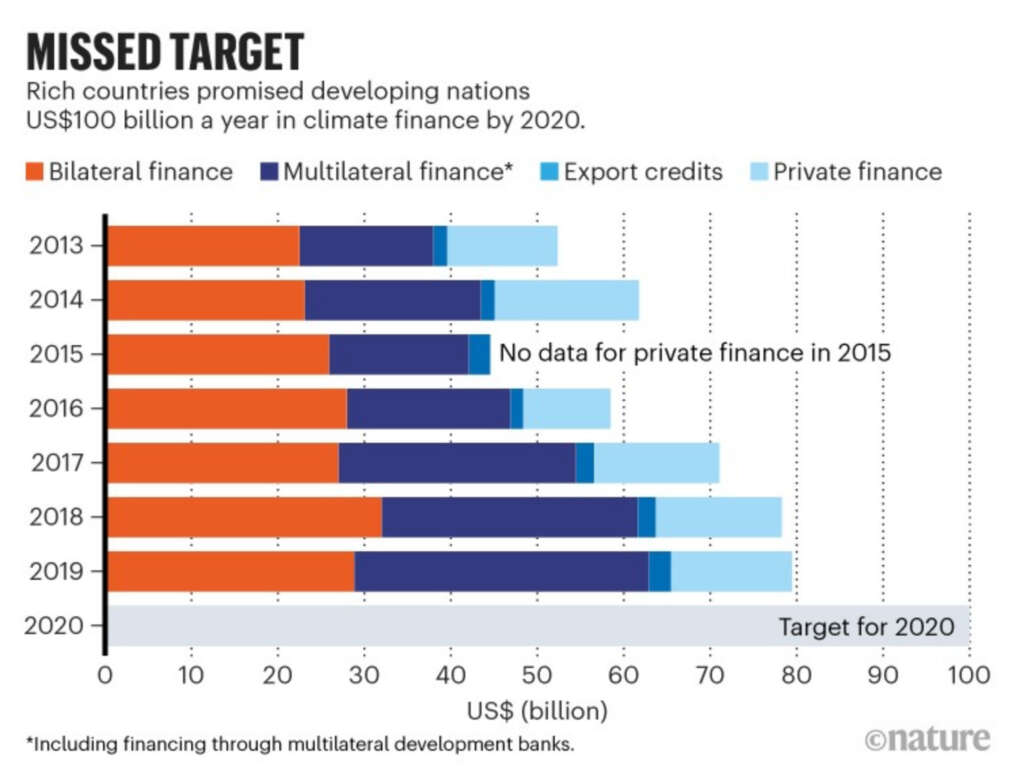

Six years hence, our fears have been confirmed. Rich countries have consistently failed to meet the minimum obligations with respect to the mobilization of financial resources to support developing countries in their efforts to address the climate crisis.

As this graph from Nature magazine shows, while the figures are rising, the minimum yearly target of USD 100 billion has consistently been missed.

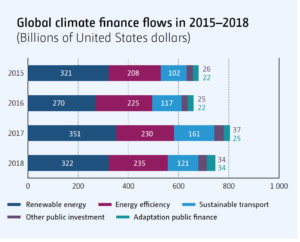

While financial support to poor countries remains inadequate, money continues to flow for a whole slew of climate related spending. The UNFCCC estimates the amount of climate finance circulating to be around 746 billion in 2018. Much of these funds go to supporting renewable energy projects (43.5 %) followed by energy efficiency (31.5), and sustainable transport (22.9). An estimated 34 bn go to supporting adaptation representing a mere 4.5 % of total global flows.

Furthermore, much of the resources are directed towards developed countries or countries transitioning to market economy, or so called Annex 1 countries. Only a fraction of the finance flows, less than 12%, are going to non-Annex 1 countries.

Between 75-80% of international public finance flows go to mitigation projects, with support for adaptation representing only around 20-25% of total flows from a combination of bilateral and multilateral climate finance, and from climate finance from multilateral development banks (MDBs).

Loss and Damage

The Promise:

Article 8 of the Paris Agreement recognized the need to “avert, minimize, address loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change, including extreme weather events and slow onset events, and the role of sustainable development in reducing the risk of loss and damage.” The agreement reaffirmed the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage as the main vehicle under the UNFCCC process. The problematic phrase “and in a manner that does not involve or provide a basis for liability or compensation nor prejudice existing rights under international law” was removed in the final text of the agreement but it appeared as a clause in the Decisions to Implement the Agreement. It remains unclear how the mechanism will work to compensate for losses and damages already felt by developing countries

Where are we now:

Loss and Damage continues to be a contentious issue in the COP. On the one hand you have developing countries continuing to demand compensation from rich countries for long term damage caused by climate change, and industrialized nations remaining reluctant to commit funding.

Negotiations have zeroed in on a proposed text that will create a “technical assistance facility” to channel financial support to affected communities.

The rhetoric around the need to help vulnerable communities continues but the promises continue to be empty ones, not backed up by concrete actions. As this report from the Guardian underscored : “The EU, and in particular the U.S., have been reluctant to back a developing country proposal for a clear commitment to supply future funding for impacted communities. They worry that approving broader claims of historic responsibility for causing global warming would be a blank check to cover the enormous damage climate change is already causing around the world.”

The patience of poor countries is running out. New proposals have been put on the table that go beyond the voluntary offers of rich countries. There is the proposal by Barbados to use 1% tax on sales revenues from fossil fuels, which could raise $70 billion per year.

On the issue of liabilities which Paris skirted around with the problematic reference in the decisions text, NPR reported the announcement of island nations Tuvali and Antigua, and Barbuda on the formation of a new commission to enable small island countries to seek compensation through international courts.

In 2019, the Santiago Network was established as part of the Warsaw International Mechanism on Loss and Damage to “avert, minimize and address loss and damage and to catalyze technical assistance for the implementation of relevant approaches at the local, national and regional level, in developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change.”

States however stopped short of establishing a clear funding mechanism. And as the Guardian report pointed out “That’s what is missing here – a way of funding the loss and damage that has been inflicted on the world’s poor by a problem they did the least to cause”

While the Glasgow Climate Pact agreed to provide funds to the Santiago network to support technical assistance, it stopped short of establishing a new funding mechanism for loss and damage. Instead Parties decided to set out a process to “determine modalities for the management of funds provided for technical assistance under the Santiago network and the terms for their disbursement.” (Decision on Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage)

As a Reuters report from COP26 noted: “The Glasgow Climate Pact, after resistance from the United States, the European Union and some other rich nations, failed to secure the establishment of a dedicated new damages fund vulnerable nations had pushed for earlier in the summit.

Institutionalizing False Solutions

The Paris Agreement created a new mechanism to contribute to the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions and support sustainable development (the dual purpose of the old Clean Development Mechanism). The new mechanism will constitute “cooperative approaches that involve the use of internationally transferred mitigation outcomes towards nationally determined contributions.” This mechanism, much like CDM will provide the space carbon offsets which have been criticized as incentives for polluters and corporations (see Focus report Costly Dirty Money-Making Scheme)

As the Climate Space pointed out: The Paris Outcome promotes techno-fix solutions like Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), bioenergy with CCS, and geoengineering. These are phantom technologies that won’t work, but will give their proponents an excuse to keep profiting from fossil fuels.

What has happened:

At the heart of the issue of false solutions is the concept of net zero, which climate scientists have criticized calling it a “dangerous trap”. In their article Net Zero a Dangerous Trap, scientists James Dyke, Robert Watson and Wolfgang Knorr lamented:

“We have arrived at the painful realisation that the idea of net zero has licensed a recklessly cavalier “burn now, pay later” approach which has seen carbon emissions continue to soar. It has also hastened the destruction of the natural world by increasing deforestation today, and greatly increases the risk of further devastation in the future.”

Nature-based Solutions

As Focus testified in the Peoples Tribunal against the UNFCCC held in Glasgow:

“Nature based solutions have become a central component of the Paris Agreement. They are particularly deceptive because they can include just about any kind of environmental project and techno fix. What they will not actually do is reduce emissions, nor prevent the damages of extractive industry, industrial agriculture and food systems and global trade.”

Most prominent in Nature Based Solutions is the concept of “net-zero”, a particularly insidious and dangerous form of offsets, that reduce nature to a service provider for offsetting corporations’ pollution and protect the profits of those corporations most responsible for the climate chaos. Far from ‘keeping 1.5 degrees in reach,’ Net zero commitments will take countries in the opposite direction of cutting GHG emissions.

As in the Green Economy and Blue Economy, Nature Based Solutions will deepen financialisation of nature, and enable “nature-based dispossessions,” and the enclosure of living spaces of indigenous peoples, peasants, and other forest-dependent communities on a massive scale.

Pathway of False Solutions

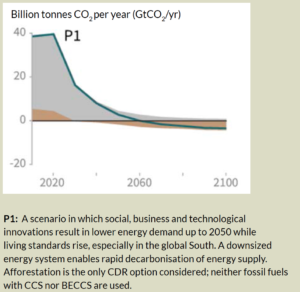

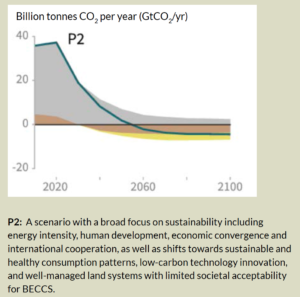

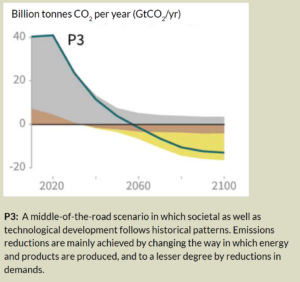

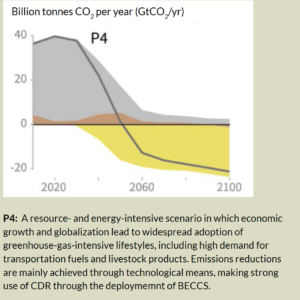

A 2018 IPCC report provided 4 illustrative model pathways for limiting warming to 1.5 oC. As explained in a report on how net zero targets disguise climate action issued by several groups:

“The four scenarios show that the more GHGs released into the atmosphere through fossil fuel and industry (the grey area above the horizontal line), the more would have to be removed from the atmosphere using agriculture, forests and other land use (AFOLU – shown in brown) or BECCS – (shown in yellow) below the horizontal line.”

Pathway 1 is a scenario of rapid decarbonization of energy supply. In this pathway, afforestation is the only carbon dioxide removal (CDR) option considered.

The main feature of Pathway 2 is the shifts towards sustainable and healthy consumption patterns, low-carbon technology innovation, and well-managed land systems, but includes bio-energy, carbon capture and storage (BECCS) option;

Pathway 3 considered a “middle-of-the-road scenario” is a scenario where “emissions reductions are mainly achieved by changing the way in which energy and products are produced, and to a lesser degree by reductions in demands.”.

Pathway 4 is really a business as usual scenario where “ economic growth and globalization lead to widespread adoption of greenhouse-gas-intensive lifestyles, including high demand for transportation fuels and livestock products and emissions reductions are mainly achieved through technological means, making strong use of CDR through the deployment of BECCS.”

Conclusion

In Paris six years ago, climate justice activists already warned that the Paris Agreement, despite its aspirational goal to limit warming to 1.5 C, was not enough to avert the impending climate catastrophe and that the deal that is touted to save the world could actually end up burning the planet.

Fast forward to 2021, what we see is that the already wholly inadequate plan forged in Paris, has been further watered down in Glasgow. In the face of the continuing failure of States to rise up to the existential challenge of climate change, it again falls on us, the people to spearhead and lead the more radical actions necessary to avert an impending catastrophe.

What does this mean for grassroots movements?

-

- The Failure to avert the climate catastrophe will affect poor and marginalized communities the most.

- The developments since Paris and now Glasgow show the tremendous push by corporations and States for ‘pathways’ that are anchored on market based, business as usual solutions.

- This is a critical moment for the climate justice struggle to push real solutions.

What Can We Do?

-

- Make on the ground campaigns against mining and extractivism, big dams, key parts of the resistance to unsustainable climate pathways.

- Forge stronger connections and convergence with broad campaigns against false and nature based solutions, and for greater corporate accountability.

- Join mobilizations at community, national, regional and global levels to resist policies and projects that exacerbate the climate crisis, and continue to amplify the calls for radical climate actions.