2020 June 4

This situationer provides a general overview of COVID-19 in Cambodia, as it impacts on four broad dimensions: health, political, economic, and socio-cultural. The data and information were compiled from various sources including official government pronouncements, news reports, coronavirus resource centres, organizational statements, and notes from the field by the author. The COVID-19 situation is still rapidly evolving, and this briefer only covers a period of four months from the first reported case of COVID-19 in the country (from end of January to beginning of June). Furthermore, this situationer does not attempt to present the complete picture nor to provide the comprehensive details of the impacts of COVID-19 in Cambodia but rather to focus on important highlights so that it can be used as a reference material for further assessment or study.

Public Health and Healthcare

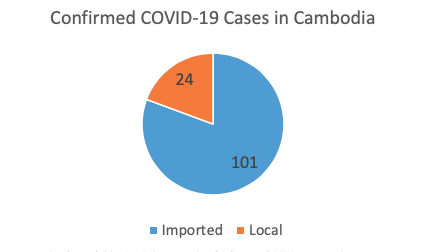

Figure 1. Confirmed COVID-19 Cases in Cambodia as of 2020 June 4. Source: Communicable Disease Control Department of Cambodia’s Ministry of Health (CDC-MoH), data retrieved from https://covid19-map.cdcmoh.gov.kh/

COVID-19 Cases

Cambodia confirmed its first positive case of COVID-19 on 2020 January 27: a 60-year old Chinese man from Wuhan—the epicentre of the coronavirus outbreak in China—who arrived at the seaside town of Kampong Som, Southern Cambodia. In the same coastal city on February 13, the Westerdam cruise ship was allowed by the Cambodian government to dock after being denied entry into Japan, Taiwan, Thailand, Guam, and the Philippines. The World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General in a February 12 media briefing on Ebola and COVID-19 outbreaks called the move an example of “international solidarity.”

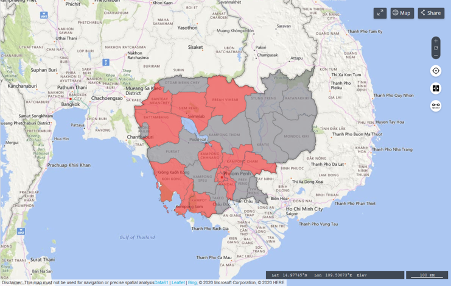

As of June 4, the MoH has reported 125 COVID-19 confirmed cases—54 Cambodian, 40 French, 13 Malaysian, 5 British, 3 Chinese, 3 Vietnamese, 2 American, 2 Indonesian, 2 Canadian, 1 Belgian—with 123 fully recovered. At the time of writing, only two active cases remain—a Cambodian man who returned to the country on May 20 from the Philippines and a woman who returned home from the United States via South Korea. Cases were reported in 13 out of 25 provinces of the country (see Table 1 and Figure 2). Cambodia has reported a recovery rate of 98 percent and ranks 9th out of 12 Southeast Asian countries in number of confirmed COVID-19 cases (see Table 2).

Table 1. The spread of coronavirus infection in Cambodia’s provinces.

| Province (ខេត្ត) | Geographic Location | Confirmed Cases |

| Kampong Som (កំពង់សោម) | Southwest | 40 |

| Phnom Penh (ភ្នំពេញ) | South-central | 30 |

| Kampong Cham (ខេត្តកំពង់ចាម) | Central | 16 |

| Battambang (បាត់ដំបង) | West | 8 |

| Siem Reap (ក្រុងសៀមរាប) | Northwest | 7 |

| Banteay Meanchey (ខេត្តបន្ទាយមានជ័យ) | Northwest | 5 |

| Kep (កែប) | South | 4 |

| Tboung Khmum (ខេត្តត្បូងឃ្មុំ) | Central-east | 4 |

| Kampong Chhnang (ខេត្តកំពង់ឆ្នាំង) | Central | 3 |

| Kampot (ក្រុងកំពត) | South | 2 |

| Kandal (កណ្ដាល) | Southeast | 2 |

| Koh Kong (ខេត្តកោះកុង) | Southwest | 2 |

| Preah Vihear (ព្រះវិហារ) | North | 2 |

Source: author’s rendering. Data retrieved from https://covid19-map.cdcmoh.gov.kh/

Figure 2. Coronavirus outbreak in Cambodia. Provinces with reported cases of COVID-19 are marked in red. Map by: Open Development Cambodia, ©OpenStreetMap contributors ODbL, © CartoDB CC-BY 3.0, retrieved from https://bit.ly/2ygTTSJ

Notably, Cambodia has registered zero new COVID-19 confirmed cases for 38 days in a row from April 12 to May 20. However, the MoH stated that the country is still in the first wave of COVID-19 and there is a risk of sudden spike in infections if people do not take precautions. Questions also remain on the reliability of official number of positive cases considering the country’s low testing rate of only about 200-500 tests per day.

Healthcare System

According to the Health Strategic Plan 2016-2020 of Cambodia published by the Department of Planning and Health Information, challenges to the country’s healthcare system include the “limited capacity of public health services to deal with diseases and health problems related to chronic diseases, non-communicable diseases, and public health emergencies such as pandemics of emerging/re-emerging infectious diseases, as well as disaster preparedness and response.” The plan also cited the challenges in effective health service delivery due to the shortage of competent health personnel in health facilities within the health system.

There are 8,488 private healthcare facilities in the country and more than 1,000 public healthcare facilities, including national hospitals, provincial referral hospitals, and district health centres. Three hospitals in the capital city of Phnom Penh—Khmer-Soviet Friendship Hospital, National Pediatric Hospital, and Kantha Bopha Hospital—were designated as dedicated medical facilities to test for and treat COVID-19. The Institute Pasteur du Cambodge (IPC) was selected as the WHO International Reference Laboratory for COVID-19 testing. The MoH also identified 25 provincial referral hospitals for COVID-19 cases outside the capital.

In its 2020 World Health Statistics, the WHO reported that Cambodia has a doctor-to-population ratio of 1.9 for every 10,000 people, the second lowest in Southeast Asia after Papua New Guinea (0.7) According to a March 25 statement by the government, Cambodia has over 20,000 health practitioners, with more than 2,000 of them ready to combat the coronavirus pandemic. However, local hospitals in the districts outside of Phnom Penh grapple with inadequate hospital staffing, limited diagnostic capacity, and insufficient resources. Local pharmacies and public health centres are also faced with a limited supply of medicines and personal protective equipment. For instance, COVID-19 Cases #121 and #122 who were admitted at Banteay Meanchey and Kampong Chhnang provincial referral hospitals were transferred to the Khmer-Soviet Friendship Hospital in the capital city on May 8 to receive further treatment.

A community member from Lor Peang, Kampong Chhnang said that in their village, those who go to the public hospitals to get checked but are not showing symptoms of COVID-19 are just asked to go back and stay at their homes. To address the insufficient physical infrastructure for healthcare delivery, more than 3,000 rooms of hotels, schools, and other public buildings across the country have been converted to receive COVID-19 patients.

Table 2. Status of Southeast Asian COVID-19 cases as of 2020 June 4. Mortality rate is calculated as follows: number of deaths divided by number of confirmed cases. An important consideration is that there is no centralized data on COVID-19 testing and most countries do not provide official reports on tests performed. Furthermore, the data changes rapidly and might not reflect some cases still being reported.

| Country | Number of Cases | Deaths | Recovered | Mortality Rate (%) | Recovery Rate (%) |

| 1. Singapore | 36,922 | 24 | 23,582 | 0.07 | 63.87 |

| 2. Indonesia | 28,818 | 1,721 | 8,892 | 5.97 | 30.86 |

| 3. Philippines | 20,382 | 984 | 4,248 | 4.83 | 20.84 |

| 4. Malaysia | 8,247 | 115 | 6,559 | 1.39 | 79.53 |

| 5. Thailand | 3,101 | 58 | 2,968 | 1.87 | 95.71 |

| 6. Vietnam | 328 | 0 | 302 | 0.00 | 92.07 |

| 7. Myanmar | 233 | 6 | 145 | 2.58 | 62.23 |

| 8. Brunei | 141 | 2 | 138 | 1.42 | 97.87 |

| 9. Cambodia | 125 | 0 | 123 | 0.00 | 98.40 |

| 10. Timor-Leste | 24 | 0 | 24 | 0.00 | 100.00 |

| 11. Laos | 19 | 0 | 18 | 0.00 | 94.74 |

| 12. Papua New Guinea | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0.00 | 100.00 |

| SOUTHEAST ASIA | 98,348 | 2,910 | 47,007 | 2.96 | 47.80 |

| WORLD | 6,538,456 | 386,503 | 2,828,468 | 5.91 | 43.26 |

Source: https://www.covid19projections.com, data from the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Centre, retrieved from https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

Politics and Governance

Border Closures and Travel Restrictions

The Cambodian government closed all its 19 international land border crossings with neighbouring countries Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam late March. Restrictions were also imposed on the entry of foreigners from countries with high number of reported COVID-19 cases including the United States, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain. The directive was then expanded to also include the suspension of visa exemption policies, the issuance of tourist visa, e-visa, and visa on arrival to all foreigners by end March. Furthermore, an order was issued compelling all those who plan to enter the country to apply for a visa in advance and provide a COVID-19-free medical certification or risk being denied entry.

On April 9, an inter-provincial travel ban was put in place across the country for one week in a move to stem the spread of COVID-19 during the Khmer New Year. Inter-district travel was still permitted and Phnom Penh and the bordering Kandal Province were considered as a single area where people were allowed to freely travel within, but not to cross provincial borders. The order permitted continued transportation of goods, medical response services such as ambulances and fire trucks, essential public services like waste collection, and the movement of those serving in the military and government. In addition, all transports of garment workers with permission from the Ministry of Labour (MoL) were allowed. During the Khmer New Year, about 30,000 garment workers went on leave; about 15,000 came back to Phnom Penh and they were mandated to undergo 14-day quarantine either in designated schools or in their own homes or rented rooms.

On May 20, the ban on the entry of foreigners from Iran, Italy, Germany, Spain, France and the United States was lifted. However, those who want to enter Cambodia must present a health insurance documentation of at least 50,000 USD for the duration of their stay in the country. They also must adhere to the government’s measures and policies, including compliance with quarantine protocols. According to Minister Mam Bun Heng of the MoH, “All travellers, including Cambodians and foreigners who arrive in Cambodia must be sent to waiting rooms to test for COVID-19 and wait for a result from the Pasteur Institute. In case one or many travellers are detected with COVID-19, other passengers on the same trip must be quarantined for 14 days.

LOCKDOWN. Border at Sampov Loun District, north-western Cambodia. Border checkpoints with Cambodia in Sa Kaeo Province, Thailand were ordered closed from 2020 March 23. Battambang, Cambodia. 2020 March 26. Photo by Galileo de Guzman Castillo.

National Committee

On March 18, the Cambodian government established a national committee composed of ministers, heads of the military and police, and provincial governors, and headed by the Prime Minister to coordinate efforts against the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the government statement, “the committee will be responsible for the formulation of policies and national strategies, taking the lead and coordinating the implementation of measures at inter-sectorial and inter-institutional levels both at the national and sub-national levels to prevent, control and manage the COVID-19 outbreak.”

Law on National Administration in the State of Emergency

In late March, Prime Minister Hun Sen declared that the government was considering requesting King Norodom Sihamoni to place Cambodia in a state of emergency in response to the coronavirus crisis. On April 10, the National Assembly of Cambodia unanimously adopted the draft law on state of emergency. A week after, the Senate gave its approval. The Constitutional Council of Cambodia, tasked to review the draft law’s adherence to the Constitution unanimously approved it on April 27. The draft was then forwarded to the Royal Palace for the consent of the King who is currently in China for a medical treatment. Consequently, legal experts debated whether a delegation of powers can be exercised. On April 29, Senate President Say Chhum who is also the Acting Head of State signed the law on behalf of the King. The Khmer Times reported that Prime Minister Hun Sen said in a previous press conference that “only the King can put the country in a state of emergency after agreement with the Prime Minister and the Presidents of the legislative bodies.”

The new legislation contains a number of measures on the restrictions on the freedom of movement, expression, and assembly. It also allows the government to impose lock down on both public and private spaces in order to respond to any emergency. The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) in their April 8 statement warned that a catch-all provision, “other measures that are deemed appropriate and necessary in response to the state of emergency” gives the government unfettered powers including carrying out surveillance of telecommunications and controlling the press and social media. The draft law, fast-tracked for approval and lacking inputs from the civil society and without consultation from outside the government was also criticized by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Cambodia Rhona Smith.

Information and Communication

According to a community member in Battambang, local authorities have been going around the communities to share information and updates about the COVID-19, including how to take prevention and protection measures. While information dissemination is being done by the government, critics have warned that draconian laws are also being used across the country to silence dissent, clamp down on opposition, muzzle the media, censor publications, and impose restrictions on freedom of speech and expression.

By early March, the Ministry of Interior (MoI) was warning that anyone who spreads “false information” or “fake news” about COVID-19 could be jailed and face legal action. On April 7, a journalist was detained and charged with “incitement to commit a felony” for quoting an excerpt from the Prime Minister’s speech about motorbike taxi drivers on his personal Facebook page. On April 29, Human Rights Watch reported that authorities have detained at least 30 people on similar charges of spreading “false information” since January. Almost half of those arrested are linked to the dissolved opposition party, the Cambodian National Rescue Party (CNRP).

TRANSFERRAL. A local reads a tarpaulin banner with information about COVID-19 prevention and protection measures on a passenger ferry. Ta Skor Village, Kandal Province. 2020 May 2. Photo by Galileo de Guzman Castillo.

Economy and Livelihood

Work and Livelihood

In March, the Cambodian government ordered the closure of all museums, cinemas, concert halls, karaoke bars, spas, gyms, entertainment establishments, beer gardens, and casinos. Malls, supermarkets, and some restaurants have remained open but with limited services, with most only providing take away service.

Similarly, many small and local businesses have been greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. A community member from Phum Rumcheck 3 who owns an ice cream cart saw a significant decrease in income, being able to sell her product in only one village in Battambang for fear of getting infected. Notwithstanding the uncertainties, many could not afford to stay in their homes and most have decided to risk their lives to go out to find work or another way to support their family. Some were able to secure alternative sources of funds and livelihood such as raising chickens, growing vegetables in their home gardens, and borrowing from friends.

Cambodia’s garment and footwear industries have also been severely impacted by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, with the Garment Manufacturers Association of Cambodia (GMAC) estimating about 60 percent of factories affected by cancelled orders of ready-made garment exports. In a government announcement, MoL Spokesman Heng Sour said that 237 factories thus far have suspended operations and an estimated 110,000 garment workers have lost their jobs.

The garments industry, a sector that employs close to a million people and contributes almost half of Cambodia’s gross domestic product (GDP) has faced massive layoffs and loss of livelihood as factories around the country closed down. Those who still come to work are at risk of getting infected and exposing their family and community to the virus as the main mode of transport to and from their homes remains climbing onto crowded trucks. According to a local community member in Kampong Chhnang, majority of the workers cannot afford to stop working because they need to pay their debts. With the absence of a clear government policy on debt relief, workers and their families face greater risk and insecurity amid the coronavirus crisis.

At the graduation ceremony of Vanda Institute in March, the Prime Minister announced a 2 billion USD budget reserve to help Cambodia’s economy—specifically the agriculture, banking, garment, and tourism sectors—weather the economic shocks of COVID-19. To provide some form of economic relief, the government and factory owners have agreed to provide a wage support of 70 USD per month for each suspended worker—with 40 USD provided by the government and 30 USD by the factory owners. At the time of writing, however, there are still workers—especially undocumented ones—who have not received this aid.

On May 1, International Workers’ Day, representatives of the Cambodian Labour Confederation, the Coalition of Cambodian Apparel Workers’ Democratic Union, and the Cambodian Tourism and Service Worker’s Federation submitted a petition to the government for compensation and intervention amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME) has called on both national and foreign companies to bid for mining exploration licences for potential metal, copper, and gold in the provinces of Oddar Meanchey, Preah Vihear, and Mondul Kiri. In a press release in end-March, the MME stated, “We reopened the coal mining concession area [794 square kilometres] for private companies to invest in research because the area is zoned for mining extraction to supply coal-fired power plants that the government has decided to construct nearby.”

DEALING. Sign on the door of a local printing shop reads: “Please wash your hands before entering.” Almost all establishments and businesses in Cambodia have put up alcohol stations at the entrance and exit of their stores, with some also doing temperature checks. Battambang, Cambodia. 2020 March 26. Photo by: Galileo de Guzman Castillo.

Migrant Workers

Thailand is home to around 1.2 million Cambodian migrant workers, majority of them are undocumented. According to the MoI’s report, more than 90,000 migrant workers returned to the country as the land borders between Thailand and Cambodia closed late March. Banteay Meanchey saw the highest number of returnees with 9,296 migrants, followed by Battambang’s 7,694, Siem Reap’s 5,255, and Tboung Khmum’s 1,393.

All migrant workers returning to Cambodia were ordered by local authorities to self-quarantine for 14 days. An April 4 VOA Cambodia report quoted Interior Minister Sar Kheng stating, “They [migrant workers] always expect to go back to work and earn income for the family. But in this current situation, we can’t allow them back passing the border.”

According to a testimony from a migrant worker from Beng Commune, Banteay Chhmar District, Oddar Meanchey Province, “the travel bans and country lockdowns are not fair for the poor since the governments have no proper plans to feed and support the people.”

Debts and Loans

According to an April 2 report of the Nikkei Asian Review that cited data from the Cambodia Microfinance Association (CMA), the country has more than 2.6 million microfinance borrowers with loans exceeding 10 billion USD. Further, the average microloan debt of 3,370 USD per borrower is the highest in the world—more than twice the country’s GDP per capita of 1,384 USD and more than double the average annual salary—as reported by Cambodian NGOs Licadho and Sahmakum Teang Tnaut (STT).

On March 27, the National Bank of Cambodia issued a directive to all banks and financial institutions to restructure credit for loans in four priority sectors: tourism, garments, construction, and transport and logistics. There have been strong calls and demands from unions for government to compel financial institutions to restructure loans or relax loan repayment. Many Cambodian farmers are in danger of losing their lands due to failure to repay microloans as they lose their main source of income and continue to face economic hardship due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, many borrowers are in danger of getting trapped in a debt cycle of going into new debts to repay current debts, resulting in heavier economic burdens.

In an April 2 press release, the World Bank’s Board of Executive Directors announced the approval of a 20 million USD credit from the International Development Association (IDA) for the Cambodia COVID-19 Emergency Response Project. This is part of the first tranche of emergency support operations through a dedicated fast-track COVID-19 facility. On April 27, the US government announced an additional 1.5 million USD in committed funds through the US Agency for International Development (USAID) for “risk communication, community engagement, infection prevention and control, and laboratory support.”

Food and Water

The countryside faces a dire situation where the small-scale food providers themselves—farmers, peasants, agricultural workers, artisanal fisherfolk, pastoralists, forest dwellers, indigenous peoples, and rural women—are struggling to produce and provide food for their families and their communities. While many are already facing difficulties in securing food and water for their families due to the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change poses an additional burden. According to one community member in Kampong Chhnang, she anticipates a problem with the water supply as communities reel under the COVID-19 outbreak during the dry seasons. Most of their wells have already dried up and it would cost 1,000 USD to dig another one. A local from Phnom Krom, a village southwest of Siem Reap and near the northern end of the Tonle Sap Lake, shared the similar problem of water shortage.

In a fishing village at Chhnok Trou, south-east corner of the Tonle Sap Lake, community members go about their usual daily activities. According to one local, it is not that they do not worry about the spread of the coronavirus but they worry more about supporting their families, putting food on the table, and ensuring that no one in the family goes hungry. In late March, Minister Veng Sakhon from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (MAFF) declared that there is no need to panic over potential food shortages as “Cambodia has abundant supplies of staples such as rice, meat, vegetables and fish to meet demand within the country”.

DRIED UP. A Lor Peang community member shares how she and her family have been trying to cope with the impacts of COVID-19, especially on their local livelihoods. Kampong Chhnang, Cambodia. 2020 March 25. Photo by Galileo de Guzman Castillo.

In their April 28 article, “In the Mekong, a Confluence of Calamities” researchers from the Stimson Centre described the food security challenge amid the drought and COVID-19 pandemic in Cambodia. According to them, agricultural communities have suffered greatly—reeling from enduring water shortage and dwindling fish catch while at the same time grappling with persistent indebtedness and vulnerabilities. They also raised the critical issues of access and affordability: “The country’s export bans may provide localized short-term benefits but could also exacerbate supply chain disruptions and result in income loss for farmers and fishermen if not carefully managed. While cities that house the country’s elites and burgeoning middle class should be able to take steps to ensure food availability at reasonable prices, rural communities scattered in villages throughout the countryside may find their local food systems less adaptable.”

ON STREAM. Bustling local trading in a fishing village at Chhnok Trou in the Tonle Sap Lake. Kampong Chhnang, Cambodia. 2020 March 25. Photo by Galileo de Guzman Castillo.

Society and Culture

Education and Learning

Almost two months after the first reported COVID-19 case in the country, the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports (MoEYS) ordered the indefinite closure of all public and private schools nationwide. All students were then required to take home-based and online courses organised by the MoEYS and its partners.

On April 19, The MoEYS extended the school suspension and announced plans to fill the educational gap with distance and e-learning programmes accessible via television in collaboration with parents, guardians, and local authorities. However, not all possessed the means and equipment to continue their education through online platforms. A student from Battambang Province said that not all of them could participate in e-learning sessions as they lack the technology and equipment to do so. Further, those who decided to come back to their home province as they could no longer continue their studies in Phnom Penh amid the COVID-19 pandemic have had to support their family by engaging in agricultural work.

In a survey conducted by the organization Social Action for Community and Development in May, they reported that students and parents, especially those in rural communities are faced with difficulties in adopting to new educational systems such as distance learning: “These challenges include additional expenses for internet services and purchases of devices [such as computers, smartphones, iPads or tablets] as well as loss of time caused by slow internet services or disruptions.”

Future Forum Education Specialist Khoun Theara further explained the situation and challenges posed by the shift to online education: “Even in urban settings, the digital gap between the rich and poor families is still quite obvious—not every student can afford a smartphone, a tablet or a computer device that makes digital learning possible. For these reasons, the pandemic is likely to widen the educational gap further especially between the rich and the poor, urban and rural schools, and public and private schools.”

SURVIVAL. Life goes on in a local market scene at the bordering town of Thmor Kol. Battambang, Cambodia. 2020 March 26. Photo by Galileo de Guzman Castillo.

Public Gatherings

Physical distancing and wearing of masks have been observed in some places but many have described Cambodia’s environment and government measures amid the COVID-19 pandemic as “relaxed” compared to its Southeast Asian neighbours.

Late March, the Cambodian government prohibited all religious gatherings. In mid-April, the Prime Minister announced the cancellation of the Khmer New Year celebrations and appealed to the public to stay in their homes. There was no formal directive by the government to prevent people from traveling back to their home province to celebrate the Khmer New Year. However, the government warned of strict quarantine protocols in place for those who decided to do so. About 10,000 garment workers who visited their home provinces during the Khmer New Year decided not to return to Phnom Penh for fear of being quarantined, with some of them resorting to alternative livelihoods like farming.

On May 1, the government issued a directive calling on all workers to celebrate the International Workers’ Day in their homes instead of the usual organizing of protests and gatherings of unions.

Tourism

Cambodia’s tourism industry has also been one of the worst affected with the ban on public gatherings. According to the Ministry of Tourism (MoT), the COVID-19 outbreak has affected an estimated 630,000 people in the tourism sector—of which 10,000 worked in tour operations including about 6,000 tour guides, 10,000 worked in the hospitality industry, and some worked in restaurants and food service.

In April, the world’s largest religious monument visited by 2.6 million tourists annually—the Angkor Wat temple complex in Siem Reap—experienced a 99.5 percent drop in monthly revenues according to government data. According to the MoT Statistics Department, tourist arrivals at the Siem Reap International Airport had dropped nearly 60 percent since the start of the outbreak.

On May 20, the MoH advised the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts that with necessary preventive measures including practicing physical distancing and wearing of face masks, the ministry can order the reopening of more than 30 museums across Cambodia for national and international visitors starting June.

Discrimination and Loss of Social Ties

In late February, the New Straits Times reported that “79 Khmer-Muslims participated in a religious gathering in Malaysia which led to cluster transmissions of the coronavirus in Malaysia and sparked fears of an outbreak among Cambodians.” On March 17, the MoH posted on its official Facebook page an update about positive COVID-19 cases and made reference to specific groups of people who contracted the virus, including “Khmer Islam.” According to a March 23 report by the VOA Cambodia, this post led to an outburst of discriminatory and hateful comments against Cambodia’s Muslim communities both online and in daily interactions in public spaces, including markets and community areas. Khmer-Muslim communities have since reported being blamed for the COVID-19 outbreak, and facing discrimination, such as people refusing to sell or buy products from them, or to even exchange money.

The discrimination also contributed to the loss of social ties among the communities and reinforced social barriers, fomenting fear and distrust.

GATHERING. On March 8, the Royal Palace was still open for visitors. Ten days after, the Royal Palace Ministry announced the temporary closure of one of Cambodia’s most iconic cultural heritage and historical landmark. The decision came after two people tested positive on returning from a mass religious gathering in Malaysia. Phnom Penh, Cambodia. 2020 March 8. Photo by Galileo de Guzman Castillo.

[i] Galileo is a Philippines Programme Officer with Focus on the Global South. He is currently in Cambodia amid the COVID-19 pandemic, awaiting the lifting of the enhanced community quarantine in Metro Manila and the resumption of normal flight operations.