A few months ago, we convened a small meeting of trade justice, environmental justice, human rights and peace and anti-war advocates to discuss and problematize how we advance and coordinate our campaigns amidst not just of the multiple crises, but of the mainstream responses to the crises that essentially support the same corporate driven development agenda but couched in buzzwords like resilience, international cooperation, friendshoring, de-risking, ESG. In other words in the face of crises and backlash against globalization, the mainstream response is not a transformation of the global economic system but a doubling down on globalization policies under the banner of reglobalization.

We agreed in that meeting that to meet this challenge, we need to unpack the latest articulation of essentially the same pro- corporate policies and expose the real agenda behind the facade.

The book we’re launching this afternoon delves on these issues and challenges and points to ways to not only of challenge the mainstream agenda but to pathways to alternatives anchored on global ecological, economic and social justice.

At the core of the book are two main assertions in confronting the mainstream environmental politics today: 1. They are not primarily focused on the preservation of ecosystems but on accumulating capital; and 2. They are colonial in scope— how mainstream environmental politics appropriate roles- that some regions of the world, some bodies and populations need to be of service to others when it comes to environmental conditions that allow a life in dignity.

________

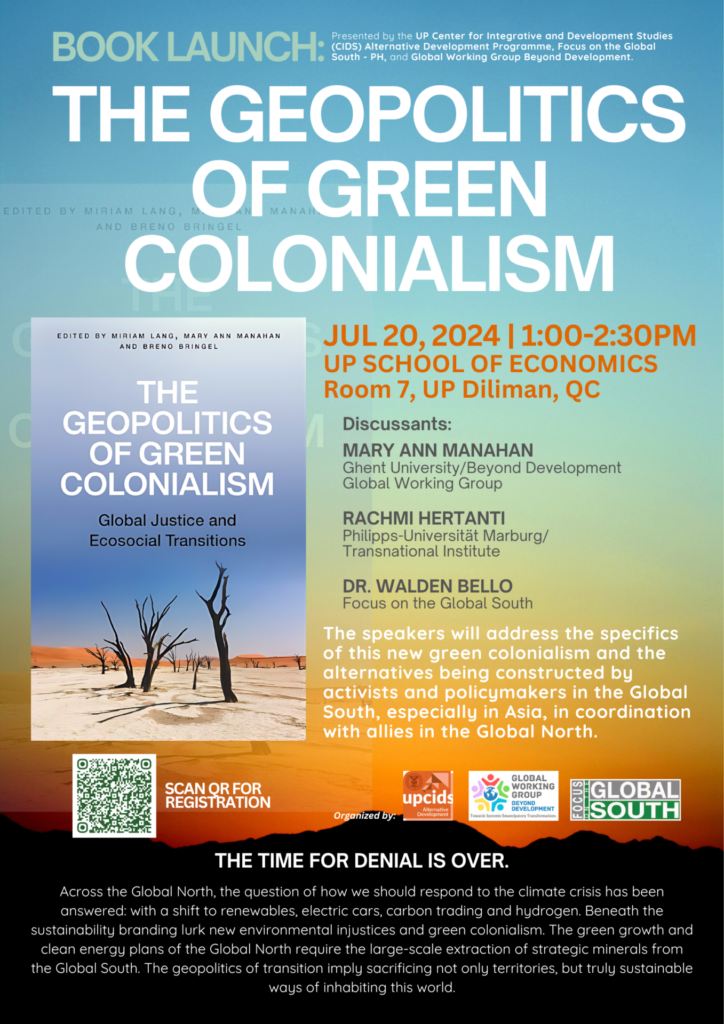

The Geopolitics of Green Colonialism: Global Justice and Ecosocial Transition

Speech for Book Launch by Mary Ann Manahan, 20 July 2024

Good afternoon, everyone! Thank you very much for coming to our book launch today. Thank you also to the organizers of the De/centering SEASIA conference, UP CIDS AltDev Program and Focus on the Global South for making it possible to launch our book in this space.

It is a great joy for me to be here with you to present the book, The Geopolitics of Green Colonialism: Global Justice and Ecosocial Transitions. A book that, although on the outside have a very gloomy cover, is the result of a lot of effort, great care, collective work and weaving. While the book is not solely focused on SEA and have a global scope, it is nonetheless relevant to the region and the theme of this conference because it tackles the themes of the geopolitics of green energy transitions, Decarbonisation Consensus, and ecosocial transitions.

The book reflects and pursues our conviction that knowledge is always a collective effort: it results from interaction, debates and exchanges among different sections of society—scholars, activists and community organizers.

Two confluences have been very central to the birthing of the book. First, the Global Working Group Beyond Development, a working group that covers the 5 continents, which is dedicated to generating knowledges around systemic, radical, and multidimensional alternatives to the prevailing neoliberal capitalist system through dialogues that combines different traditions of critical thinking. It was the meeting of this working group held in May and June 2022, in Senegal, with the support of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation in Dakar, which gave the first impetus for this book. We held a week-long debate about how we should understood the current buzzword, “just transition”, and whether this term that is so polysemic today really expressed what we are collectively seeking and aspiring for.

Second, the Ecosocial and Intercultural Pact of the South, an independent, non-partisan Latin American political platform animated by a collective of activists and activist academics from 10 countries that was formed in June 2020.

In 2022, the Ecosocial Pact, in alliance with the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington D.C. in the United States, a think tank of the left who works closely with social movements globally, set out to convene a series of South-South dialogues that involved actors and organizations from Africa, Asia, and Latin America around what would be a just global transition. One of the tangible results of this initiative was a Manifesto from the Peoples of the South: For an Ecosocial Energy Transition. In Southeast Asia, Focus on the Global South, Friends of the Earth Malaysia, NGO Forum on ADB, Consumers Association of Penang, Third World Network, and many individuals including Walden Bello, who’s joining us remotely were proponents of the manifesto. The manifesto informed the conceptualization and content of the book.

To bring out this book into the world, we have three editors that got together:

- Breno Bringel, from Brazil, member of the Ecosocial Pact of the South

- Miriam Lang, of German nationality but based in Ecuador for 18 years, and belonging to both processes

- Me, from the Philippines, one of the co-coordinators of the Beyond Development Global Working Group.

The three of us have one foot in activism and social organizations and the other in the university. The three of us have also lives and struggles gravitate in the global South, but we also have multiple links in the global North.

Why the book?

In the introduction of the book, we said that we have witnessed many debates and practices that aim to address the climate crises and ecological collapse in different regions of the world. However, especially in the United States and Europe, we were struck by the constant invisibility of the global South in these debates and the naturality with which it is assumed that all the “critical minerals” and tracts of land needed for all the electric cars, the gigantic solar or wind installations and the digitalization of production that they promise to achieve green growth will come from somewhere.

Policy documents and plans for green growth rhetorically focus on “green alliances” and “sustainable raw materials” (European Commission, 2019) to overtake the other world powers in the race for geo-economic primacy, without detailing how extractivism will become “sustainable” and North-South relations less asymmetrical. The concerns of the European Union and the US for example, are rather focused on obtaining the necessary amounts of these so-called critical minerals.

We use the global South here not only as a geographical category but as an dynamic geo-political and epistemic constructions. These means that we recognize that there are also many Norths in the South and Souths in the North.

With the lack of voices and critical perspectives from the global South, we decided to bring researchers, activists, experts, long-time companions on the road, and comrades-in-arms to write this book, as a critical and urgent contribution to the debates about “just transitions”.

We also decided that the book deliberately adopts a perspective from the global South and foreground global South voices. All the authors have backgrounds that combine activism with knowledge production in a variety of settings. They do not write about struggles for eco-social transitions, but from within these struggles.

Key Arguments of the Book

Let me now bring your attention to the core arguments of our book. We argue that green colonialism, some of our contributors call it as energy and climate colonialism, is the new phase or iteration of environmental politics today. This environmental politics is shaped by two characteristics.

First, it is not primarily focused on preserving complex ecosystems, but on accumulating capital.

Second, this environmental politics is colonial in scope: that means they assume that some regions of the world, some bodies and populations need to be of service to others when it comes to environmental conditions that allow a life in dignity. These are what we call as sacrifice zones.

First Argument: environmental politics is focus on capital accumulation

- Neoliberal reason (to borrow the words of French philosophers Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval’s in “The New Way of the World: On Neoliberal Society”) has completely permeated environmental governance, at the global scale at least but also at national and local scales.

- It is argued that money is central to environmental conservation and that huge amounts of funding are required to ‘save nature’ and combat climate change. Private investments are needed because public investments are ‘not enough’.

- This profit imperative prevails over the ecological effectiveness of what is and can done. In other words, the determinant for the ‘feasibility’ of environmental measures is their profitability (return on capital), not their effect on ecosystems.

- This new environmental politics, which Latin American scholars Maristella Svampa and Breno Bringel calls as the Decarbonisation Consensus, has induced a new global agreement committed to transforming the energy system from one based on fossil fuels to one with reduced carbon emissions, based on ‘renewable’ energies. Its leitmotif is to fight global warming and the climate crisis by promoting an energy transition driven by the electrification of consumption and digitalization.

- However, it brings a dialectic or dynamic of new extraction or exctactivism—balsa wood needed for wind turbines; and lithium, cobalt, and other critical raw materials needed for green energy transition technologies, are extracted in certain frontiers, regions and territories, on the one hand. On the other, the Decarbonisation Consensus also create new areas of conservation that make lands, waters, and forests as carbon sinks, which are needed for carbon sequestration and offsets.

- The new scramble for control of the global supply chain of critical raw materials are facilitated by concrete mechanisms such as bilateral free trade and investment agreements, that lock-in resource rich countries in Asia, Latin America and Africa to become constant suppliers of raw materials for the voracious green transition of the EU and US. Rachmi, will expound on this in her presentation.

- Mechanisms for the creation of carbon sinks and offsets are meanwhile reinforced through a new brand of global environmental multistakeholderism that emphasizes a new sustainability buzzword called nature-based solutions.

- Multistakeholder initiatives around nature-based solutions entrench the valuation of Nature as capital, an economic asset that fundamentally has a price-tag on all its dimensions, services and functions (e.g. water purification by pristine watersheds or carbon sequestration of forests and oceans).[i] It consequently draws Nature into financialised markets, simultaneously locking ecosystems into the boom and bust of the financial world, as well as dislocating forests, oceans, and lands from their places of origin, histories, relations with people and communities that rely on them.[ii]

- Under these conditions, for example, the financialization of the Amazon tropical forest is seen as an enormous business opportunity:

- Multistakeholder alliance THE LEAF COALITION: “eliminating deforestation in the Amazon by 2031 could generate as much as $18.2 billion”

- World Economic Forum: “Biodiversity credits can create more than $10.1 trillion in business opportunities”

- Valuing nature as capital for accumulation strategies have far-reaching implications. First, it assumes that Nature can only be saved if a price tag is put on it. Second, it requires new modalities, global rules, and decision-making infrastructures that facilitate the involvement of corporate and financial actors to push for its mainstreaming at multiple governance levels. An example is the creation of the Natural Capital Protocol[iii], a new standardised framework for business to measure, manage, and value their impacts and dependencies on Nature. This was an offshoot of the Natural Capital Declaration that was launched during the 2012 Rio+20 Summit. It ushers in the capitalist invasion into Nature that values 17 ecosystem services and 16 biomes in economic terms, worth at least EUR15-50 trillion.[iv]

Second Argument: this new environmental politics is colonial in scope

- The history of colonialism has always had a component related with the governance of nature: for example, the destruction of very complex and functional indigenous irrigation systems to artificially generate technological dependency on western hydraulic technologies. The deforestation of virgin forests in service of ship building or for the timber needs of the colonial capital/center.

- The extractivist logic and colonial violence against bodies, territories and ecosystems have persisted since the 15th

- Today the material conditions and means of justification have changed: some territories of the world are destined to be plundered and others rather for capitalist accumulation through a greening imperative, which reproduce an unequal North-South Relations.

- Four dimensions unfold in the relation between global North and South – and all four have a strong dimension of colonial appropriation:

- There is an assumption of unlimited reserve of (critical or not) raw materials found in the global South.

- There is the imposition of certain formats of conservation (fortress conservation, carbon offsets). For example, the 30×30 Plan under the Post-2020 Convention on Biological Diversity promotes this fortress conservation—or conservation without people that threatens to displace indigenous and forest-based communities.

- The global South as dumpsites for toxic and electronic waste from the energy transition and digitalization of the economy (immaterial…)

- Projecting the South as new markets for high-priced renewable technologies in the context of the asymmetric architecture of global trade, thus perpetuating unequal exchange.

- It is baffling how in global debates around green energy transition, geographies where that appropriation will take place are imagined or represented as without people or conflict. We are incensed at how certain landscapes, bodies and whole populations in the global South are rendered disposable and invisible. This is how the mutual constitutiveness of colonialism and capitalism that have existed since the 15th century are re-enacted today: geographies destined for accumulation prey on other geographies, destined to be plundered.[v] While today’s green colonialism is exactly as materially expropriating as other colonial relations before, it complicates resistances by proclaiming itself environment-friendly and indispensable in order to grant humanity a future, a journey where the racialized populations of the global North and South apparently still have no seat.

- These practices are continually fed by neocolonial imaginaries. For example, the idea of ‘empty space’, typical of imperial geopolitics, is often used by governments and corporations. In the past, this idea, which complements the Ratzellian notion of ‘living space’ (Lebensraum), generated ecocide and indigenous ethnocide, and later served to promote policies of ‘development’ and ‘colonisation’ of territories. Today it is used to justify territorial expansionism for ‘green’ energy investments. In this way, large tracts of land in sparsely populated rural areas are seen as ‘empty spaces’ suitable for the construction of solar panels, windmills or hydrogen plants, disregarding historical and political, cultural and socio-economic relations that exist between those lands and its inhabitants.

- A concrete manifestation of green colonialism for example happens in the Ecuadorian tropical forest, deforestation is being pushed by Chinese appetites for the extremely light balsa wood tree, which is used in the building of wind turbines. In the Maghreb, a region in Northwest Africa, pastoralists lose their lands and water to huge solar farms which are built to provide ‘green energy’ to Europe. In Indonesia, critical raw materials in farming communities are extracted for the electric vehicle batteries under a new regime of resource nationalism. All these recent practices of appropriation and dispossession are labelled as ‘green’, which provides them with a whole new legitimacy in the face of today’s struggles for livelihoods or territories.

Organization of the book

We have organized the book into three parts:

The first, entitled “Hegemonic Transitions and the Geopolitics of Power”, is dedicated to the critique of colonialism and coloniality that prevails in “green” policies. We have here examples from Latin America, Africa, and a critical analysis of the green deals of the US, EU and China.

The second part, “Analysing Green Colonialism: Global Interdependencies and Entanglements” explores how, in the neoliberal world-system, every possible alternative to green colonialism is shaped by structural conditions, institutionalized at different levels of governance. In this section, Rachmi has shared how free trade agreements serve as a very powerful obstacle for a country such as Indonesia to forge its own path to eco-social transitions.

The third section focuses on the alternatives, which is perhaps one of the most important sections of our book. Entitled, “Horizons towards a dignified and habitable future”, we bring together a few voices from different schools of critical thinking. In this section, we present examples of proposed and on-going processes ofecosocial transition, with examples from a national energy transition process in Colombia, women-led food sovereignty movement in Bangladesh, ecofeminist alternatives in Africa, re-imagining the world of work and labor, imagining degrowth from a feminist perspective, and what a new eco-internationalism constitute.

To a huge extent, the book combines what Walden has coined in the early 2000s as deglobalization and Arturo Escobar’s resistance and re-existence—deconstruction/criticism and reconstruction/proposals. The middle section, however, gets out of this dual logic by outlining the architecture, institutions and actors that shape this new phase of environmental politics.

Finally, let me end by saying that despite the enormous challenges posed by the Decarbonisation Consensus and hegemonic environmental politics of today, we remain hopeful. It is the message of our book after all. As activists and activist scholars, we find the urgency to foreground the need to radically change the way we produce, distribute and consume—the way our economies and societies are organized; of reforging and recovering relations between society and Nature; and of dismantling internal and international structures and processes of extractive and asymmetrical North-South relations. These elements of alternatives that emphasize resistance to green and energy colonialism, but also forms of re-existence that constitute the (re)imagining and building of a better world. There can be no eco-social transition without global justice in all its dimensions.

We hope that the book will provoke, inspire and move you to act toward a truly ecosocial transition built on justice, respect of Nature and radical and systemic alternatives.

Thank you for listening!

Reference:

[i] UNEP. Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication – A Synthesis for Policy Makers, 2011 http://www.unep.org/greeneconomy/Portals/88/documents/ger/GER_synthesis_en.pdf (Last accessed: January 17, 2023).

[ii] James Fairhead, Melissa Leach and Ian Scoones. “Green Grabbing: a new appropriation of nature?” The Journal of Peasant Studies, 39(2) (2012), 237-261.

[iii] The protocol complements other national-level accounting frameworks such as the UN System of Environmental Economic Accounting (UNSEEA) implemented by governments through the World Bank-led Wealth Accounting and Valuation of Ecosystem Services (WAVES) global partnerships.

[iv] Robert Costanza, et al. “The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital.” Nature, 387(6630) (1997), 253–260.

[v] Horacio Machado Aráoz. “Ecología política de los regímenes extractivistas. De reconfiguraciones imperiales y re-existencias decoloniales en nuestra América”. Bajo el Volcán, 15(23) (2015): 11-51.