December 2024

The so-called ‘Asian century’ is a veritable jumble of contradictions. While the Asia Pacific is considered amongst the most dynamic in the world, its embrace of neo-liberal globalisation has thrust the region into the vortex of, what analysts have termed, the ‘multiple crisis’ – a toxic fusion of political, economic, social and ecological crises that overlap and feed on each other. Many countries in the region (as this paper shows) are caught in the current global wave of far-right authoritarian nationalism even as they fail to combat economic inequality, unemployment, food crisis and climate shocks.

Four years after the COVID-19 pandemic wreaked havoc across the region, the usual suspects are cheering what they claim is a ‘post-COVID recovery’ and an acceleration of globalization. Reports from agencies such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Asian Development Bank (ADB) indicate that a robust post pandemic recovery is underway in Asia with growth projections at around 4.9 percent for 2024 and 2025. These figures are much higher than those for Latin America, Africa, Europe, and North America.

The ADB’s Asia Regional Integration Center (ARIC) that tracks trade and investment integration cites Asia as the world’s second most integrated region, after the European Union (EU). Some 60 percent of the value of Asia’s trade is conducted within the region. While South Asia is an outlier, there has been a deepening of economic interdependence between China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) bloc with the 2022 Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) expected to further propel integration among its 15 partner countries[i]. Asian Transnational Corporations (TNCs) now dominate the Fortune Global 500 list. When the ranking was first published in 1990, there were zero Chinese companies in the list. The 2023 list has 133 from China, 41 from Japan, and 8 from India with Asian TNCs comprising 42% of the global total. North America is at 31%, Europe at 24% and the rest of the world at 3%.

Another list paints a contrasting picture. Compiled by the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the 2024 Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (global MPI) shows that out of the 1.1 billion who live in acute multidimensional poverty more than 1/3rd live in South Asia. Much of Asia’s poor continue to suffer from acute deprivations in housing, sanitation, electricity, cooking fuel, nutrition and school attendance.

Asia is also at the epicentre of current geopolitical conflicts between the US and China. The US continues to provoke China in the Taiwan Straits undermining its long held ‘One China policy’. The West Philippine and South China Seas are witness to regular clashes between Philippine Coast Guard and Chinese vessels with US vessels stoking the fire rather than de-escalating the situation.

In addition, Asia continues to be on the boil with the ongoing Israeli genocidal war against Palestine and civil wars in Yemen, Syria, and Myanmar. As we write this, a new front has opened with Israeli bombing in Lebanon and retaliatory missile strikes by Iran on Israel. In addition, the fall of the Assad regime in Syria on December 8, 2024, will push the war-torn country and West Asian region into further uncertainty and upheaval. Israel was quick to take advantage of the prevailing chaos by carrying out nearly 500 airstrikes and seizing Syrian sovereign territory.

Post-COVID, many developing countries have been hit with the nightmare of an escalating debt crisis. In Asia, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh have seen regimes fall as a result of peoples protests due to economic hardship. And predictably in all of these countries, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is back with structural adjustment policies and imposition of severe austerity measures. In Sri Lanka the economic and debt crisis resulted in a popular people’s movement called the Janatha Aragalaya (Peoples Struggle) that overthrew the corrupt and authoritarian Rajapaksa regime in 2022. Nevertheless, the Sri Lankan political elite managed to cling to power by cobbling together a caretaker government led by Ranil Wickremesinghe who continued to focus on export orientation and privatisation as the way out of the crisis. Wickremesinghe implemented a series of structural adjustment policies mandated by the debt bail out package from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). As a result, the Sri Lankan economy contracted over six successive quarters in 2022 and 2023, leading to a rise in unemployment, food insecurity and fall in real wages. It was no surprise then that the old guard neoliberal parties were booted out in the September 2024 Presidential elections and the left-wing National People’s Power (NPP) candidate Anura Kumara Dissanayake won a landslide victory. The NPP alliance then swept the November 2024 general elections winning 159 out of 225 parliamentary seats. This is now a watershed moment for Sri Lanka as people wait to see how the new government under Dissanayake will reverse the damaging impacts of the IMF, address the debt crisis and revive an economy battered by decades of neoliberal policies that have gutted industry and agriculture.

Sri Lankan President Anura Kumara Dissanayake addresses a rally of the National People’s Power coalition (photo: https://economynext.com)

In August 2024, Bangladesh’s longest serving Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina abruptly resigned after a massive student uprising. The student protests were especially triggered by a government job quota system they felt was gamed towards families friendly to the ruling regime.But the protests built on long standing frustrations by the working classes of an economic model that worked for the rich but not for them; rising cost of living, stagnant wages, increasing indebtedness and lack of employment opportunities for the youth. In addition, the Bangladeshi taka crashed, foreign exchange reserves declined and the cost of foreign debt servicing increased. As usual the Government had to go to the IMF for ‘relief’. After the protests, similar to the Sri Lanka case, a new caretaker government led by microfinance pioneer Muhammed Yunus has been installed. Yunus will not challenge the IMF conditionalities and the volatile situation in Bangladesh is not expected to ebb anytime soon.

Bangladesh students block a road during a protest against the Sheikh Hasina Government (photo https://www.middleeasteye.net/)

Predictably, trade tensions between the US and China are also playing out in the region. As a counter to the 15-nation RCEP, in which China is a key player, the Biden administration launched the 14-nation Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) in 2022 with a focus on technology, clean energy and supply chains[ii]. The attempt is to break countries from their links with China on supply chains, infrastructure and technology.

But even as Asia supposedly ‘rises’ onto the global stage, there is also the concomitant retreat of democracy, deepening inequalities, and the rise of authoritarianism in many countries in the region. This paper examines four countries that recently saw elections and elaborates how various peoples’ movements and civil society are responding on the ground to the multiple crises and challenging the continued rise of authoritarianism fused with corporate power.

In the Philippines, the May 2022 elections saw the stunning comeback of the discredited and corrupt Marcos’ dynasty with Ferdinand Marcos Junior recording a landslide victory[iii]. In the July 2023 elections in Cambodia, Hun Sen’s Cambodia Peoples Party (CPP) won almost all the seats. His son, Hun Manet was then anointed as Prime Minister signaling a continuity of dynastic authoritarian rule[iv]. In Thailand, after a decade of military rule, the fledgling Move Forward Party (MFP) surprised everyone including themselves by winning 151 seats in the May 2023 elections. But hopes were dashed as the elites exploited their judicial power and paved the way for the runner-up, the Pheu Thai Party (PTP) to form the government[v]. In August 2024, the Thai Constitutional Court delivered yet another body blow to the democratic mandate by dissolving the MFP and then also removed the PTP’s Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin. He was replaced by Paetongtarn Shinawatra, daughter of former PM Thaksin Shinawatra. In the June 2024 national elections in India, Prime Minister Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) lost its parliamentary majority for the first time in 10 years. Modi continues as PM and a resurgent opposition notwithstanding, it is business-as-usual policies in India with scant regard for human rights, undermining of the federal polity, and continued attacks on minorities.

PHILIPPINES

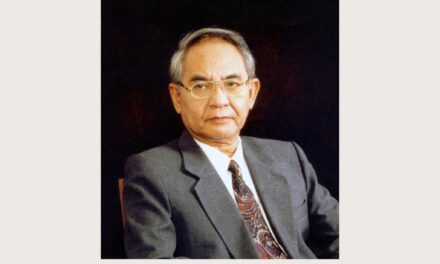

President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and Vice President Sara Duterte before the storm. 16 March 2024. Photo by Presidential Communications Office. Sourced from Wikimedia Commons.

In the Philippines, the Marcoses and Dutertes—two of the most powerful dynasties that brokered an electoral alliance in 2022—are now embroiled in a power struggle. On the one hand, by gaining control of the presidency, the Marcoses have harnessed their political capital to tighten their grip on Congress and form ‘supermajority’ blocs. With their control over the supermajority, they were able to launch an all-out offensive against the Dutertes. The allies of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. have exposed and investigated Vice President Sara Duterte’s questionable use of confidential funds. The Speaker of the House of Representatives, who is the President’s cousin, ousted the Dutertes’ allies from the House leadership. This year, the Senate led an inquiry into Philippine Offshore Gaming Operations (POGO) firms that offer online gambling services to markets outside the country, with a significant portion catering to the Chinese market. The entry of POGOs were facilitated under the administration of former President Rodrigo Duterte. The Senate inquiry was prompted by reports that POGOs have ventured not just into illegal gambling but also financial scamming, money laundering, prostitution, human trafficking, kidnapping and even murder. Another Senate investigation was initiated to look into former President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs that resulted in the killing of thousands. The Marcos administration has also resumed peace talks with communist rebels, thereby undermining Duterte’s violent anti-insurgency campaign that was hinged on the indiscriminate political repression and persecution of progressive movements.

The success of the Marcos-led offensive can be seen in the mass defection of politicians from Duterte’s political party towards that of Marcos, further consolidating the Marcoses’ political capital. Despite this, however, Sara Duterte has remained more popular than Marcos Jr. Knowing the extent of her influence, she has tactically used her mass support base to rally against Marcos and his allies. The Dutertes have organized media events and used the platform provided by the Senate investigations to reinforce the narrative that they are the victims of political persecution by the Marcoses and other political blocs.

The breakdown of the Marcos-Duterte alliance is also closely linked to the geopolitical tensions between the US and China. The Philippines’ strategic location in the Pacific positions it as a crucial area of interest for both superpowers. While the Marcoses lean towards the US, the Duterte’s favor China, thereby implicating their political survival in the escalating geopolitical tensions while also making Philippine politics a battleground for these competing influences.

But as the elites and powerful countries continue to be preoccupied with politicking, the majority of Filipinos suffer from economic, food, and climate crises. In 2023, the Philippines had the dubious distinction of being the world’s top rice importer. Reports indicate that it will maintain this undesired position in 2024 and 2025 as well. The inability of the Philippines to produce enough food domestically has led to rising food inflation and high levels of hunger. In April 2024, food inflation was at 6.3 percent making it the largest contributor to the country’s overall inflation. According to a recent survey, a staggering 14.2 percent of Filipino families went hungry in March 2024. This is the highest hunger incidence since May 2021 when it was at 16.8 percent during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Marcos regime’s knee jerk reaction to address hunger and rising food prices has been to increase imports of primary commodities. The 3.2 million metric tonnes that it imported in 2023 led to a crash in the farm gate price of rice, resulting in significant losses for farmers.

This follows on from the 2019 Rice Trade Liberalisation (RTL) law that removed all quantitative restrictions on rice and replaced these with a 35 percent tariff on rice imports. This resulted in a 56 percent increase in imports—from 2 million metric tonnes in 2018 to 3.1 million metric tonnes in 2019. As markets were flooded with imported rice, the average farmgate price nationwide reduced by 15.5 percent—from PHP 20.06 per kilogram in 2018 to PHP 16.95 in 2019.

Another policy initiative of the Marcos Jr administration has been to create a new ‘Green Revolution’ programme to boost rice yields. But so far, the production support programme continues to be largely inaccessible to the neediest small scale food providers. Also, this new programme to increase production sits easily with other pro corporate policies have led to rising debt and increase in costs of farm inputs leading to capture of peasant lands by real estate developers that are fuelling land-use conversions.

This crisis ridden and confused state of agriculture policy in the Philippines can be traced back to the 1980s to when, during the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos Sr, the country adopted a radical programme of deregulation. Subsequent administrations led by Corazon Aquino and Fidel Ramos deepened trade liberalisation. Nominal tariffs were unilaterally reduced and then subsequently eliminated on more than 60 percent of agriculture products under the 1992 ASEAN free trade area which were again furthered under the 1995 Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) at the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Over the past three decades, the Philippines has served as a textbook case of how to convert a self-sufficient agriculture economy into a highly import dependent one. Ironically much of these imports come into the Philippines from the US and EU, two of the highest subsiders in global agriculture and ardent votaries of free trade for the global south. In addition to the WTO debacle, the Philippine Government has now included further liberalisation of agricultural markets under various current FTAs such as RCEP, EU-Philippines, and IPEF. This is being robustly challenged by national level platforms such as Trade Justice Pilipinas that is working with peasant movements, trade unions, and progressive parliamentarians to reject free trade, be it at the WTO or FTAs.

The other darker side of the agrarian crisis takes the form of violent aggression by the state and the elites against peasant movements and communities resisting land grabs. This is common in far flung provinces such as the Nueva Ecija in central Luzon where Focus staff spoke with community members (identity withheld) who recounted how a peasant leader was shot dead by gunmen in front of a church in 2023. Militias and private security groups, usually in collusion with the local police, regularly harass communities who are unwilling to surrender their land rights.

Indigenous communities have been especially targeted for land grabbing owing to the weak protection they are provided by law and by the government. Often police, military, and civilian officials collude with agro-corporations or turn a blind eye to the latter’s depredations.In Quezon, Bukidnon, a plantation owned by the mayor has dispossessed a whole Manobo community numbering in the thousands and

In areas where such violence can be reported, corporations and landlords’ resort to SLAPP (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation) cases which can have equally vicious consequences. The process of ‘criminalisation’ of communities through complicated legal proceedings (along with the high financial obligations that come with it) creates a climate of fear and neutralises them from asserting their rights to progressive agrarian reform.

Farmers from Sumalo, Bataan, facing trumped up charges, face the media together with former Senator Leila de Lima, former Congressman Walden Bello, and Ampy Miciano from the National Rural Women’s Coalition to denounce criminalization of land rights struggles. November 5, 2024 in Quezon City. Photo by Joseph Purugganan.

In Sumalo in Hermosa province, a well-known peasant organisation (identity withheld) fighting for land rights received more than 50 criminal and administrative legal notices in the last 10 years. These cases, include but are not limited to: trespassing (for going through land enclosures to harvest crops), theft (from harvesting crops), grave coercion (for threatening the corporation’s armed security, libel (for speaking against the corporation in public spaces, cyber libel (for speaking against the corporation in online spaces) and estafa (for soliciting funds from community members to sustain legal obligations in the agrarian case). The local community has been entrenched in various legal proceedings for more than a decade to fend off these criminal charges including the raising of funds to bail out incarcerated peasant leaders. In a similar light, local media in collusion with corporations have also relentlessly subjected them to smear campaigns, painting their legitimate land struggles as anti-development, in an effort to place them under negative public scrutiny and erode upon the just grounds of their campaign.

Despite these challenging odds, agrarian communities are pushing back against such atrocities and injustices. Grassroots communities and people’s organisations are reaching out to lawyers, civil society organisations, national people’s movements, human rights groups, and advocacy support groups in order to fight criminalisation in the courts. Collective action has also been used to draw attention to questionable rulings. Additionally, because of the prevalence of legal attacks, people’s organisations and support groups have recognised the need for a coordinated response against the use of criminalisation as a tactic. This has meant consolidating and streamlining short-term responses to criminalisation, as well as a larger campaign for policy changes to combat SLAPP tactics.

In rare cases, intense public pressure forces the Government to retract false cases. In November 2023, former senator Leila De Lima was released from prison after nearly seven years of incarceration. Former Congressman Walden Bello writing about her imprisonment called it ‘the most spectacular frame-up in the history of the Philippine judicial system’. De Lima, he says paid the price for daring to expose and investigate the extra-judicial executions that took place in Davao when President Duterte was mayor of the city.

CAMBODIA

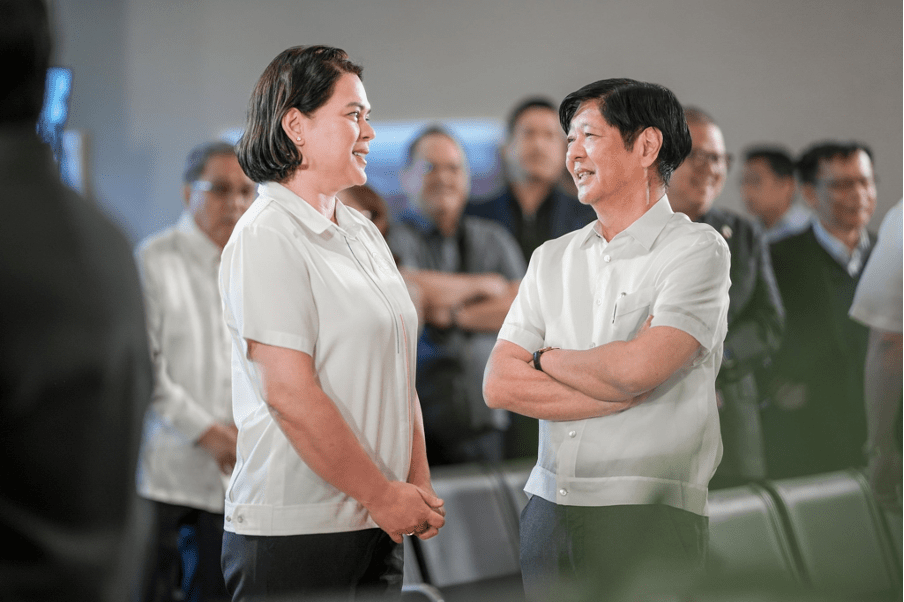

Despite the change in leadership, the country remained under authoritarian rule. (Photo https://asia.nikkei.com/)

Communities forging alternatives despite shrinking public spaces

In Cambodia, the adage that ‘the more things change, the more they stay the same’ especially rings true. In July 2023, after nearly 40 years of ruling with an iron fist, Prime Minister Hun Sen stepped down. His son and successor Hun Manet has so far continued on his fathers beaten track; with systematic repression of the opposition and civil society. Independent media has been told in no uncertain terms to stay within its limits or face closure by the regime. The radio station Voice of Democracy (VOD), one of the few independent media outlets, was shut down arbitrarily in 2023 for apparently reporting false news about Hun Manet. VOD had clarified that the article under investigation cited a government spokesperson.

On paper, while the new Prime Minister has changed the leadership of most ministries, ostensibly to bring in younger blood, a closer examination shows that almost all the new leaders come from families close to the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) and its allies. Political dynasties from middle and upper classes continue to enjoy power resulting in a continuation of the lack of trust in the government from common people[vi].

Cambodia’s economic and trade liberalisation policies are also unlikely to change under Manet. Under the ‘economic diplomacy’ programme of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation that aims to further trade, investment and tourism, the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (MAFF) is implementing programmes such as the National Agriculture Strategic Development Plan to attract foreign direct investment with conducive policies for private corporations such as access to subsidies and facilitating ease of doing business. In 2022, Cambodia signed three ambitious FTAs: the 15-nation RCEP FTA, the China-Cambodia FTA and South Korea-Cambodia FTA.

These FTAs will further expose small-scale food producers and local businesses to the vagaries of international trade. Despite its attempts to enhance exports, Cambodia has been a net food importer since the past few years and as market barriers get eliminated especially with countries such as China and RCEP members, the agriculture trade deficit will increase. There have already been reports of farmers being compelled to burn their crops or throw their produce on roads as a protest against their inability to compete with imports.

The regime is committed to private sector-led solutions to address the problems in the agriculture sector; all new plans and policies for the adoption of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology, use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), hybrid seeds and e-commerce are reliant on market-based solutions. Real issues confronting the peasantry and working classes such as struggles with household debt due to rising cost of inputs such as fuel, fertilisers, water, and seeds receive scant attention from officials in the Agriculture Ministry. It is estimated that nearly 90 percent of Cambodian farmers are in debt and loans can accrue interest up to 20 percent per month. In addition, peasants and fishers are confronted with climate change related challenges such as drought, extreme heat and floods where the state response has been inadequate at best and criminally negligent at worst.

Despite this adverse political and policy environment there are pockets of hope across rural Cambodia. In Battambang province, a region that is rife with the use of chemical fertilizers, we met Soun Somnang, a determined young agroecological farmer. During a field visit to her farm, Focus staff were introduced to her methods of creating nutrient rich fertilisers by using vegetable and fish waste and cow dung. These natural fertilisers have improved both soil health and crop quality. Her vegetables now demand a premium in the market for their superior quality and taste. She believes that her farm is also now more resilient against pests and diseases, thereby eliminating her need to rely on harmful chemical pesticides. As a woman in a field traditionally dominated by men, Somnang’s achievements are even more remarkable. Her role as a female farmer and leader in agroecology challenges gender norms and inspires other women to pursue sustainable farming practices.

To the west of Somnang’s farm is the iconic Tonle Sap, the largest freshwater lake in Southeast Asia. It is a vital resource of Cambodia that supports numerous floating villages, critically endangered water birds and other species, provides vital nutrients for farming and its fisheries are amongst the most biodiverse in the region. In the past few years, its ecosystem has been under threat from climate change and dam construction upstream on the Mekong river. 2019-2021 saw the driest three-year period for Tonle Sap that threatened its fish stocks and saw unprecedented wildfires.

The Tonle Sap region is divided into three zones for ecosystem management. The first zone covers the permanent lake area, the second includes the seasonally flooded forests and zone three encompasses the outer floodplain and agricultural areas. Zone 3 is critical for local livelihoods as it balances both the agricultural activities with the conservation of fish habitats, especially during the dry season. The Reang Penbei Tor Fisheries Community, located in Preak Luong in Zone 3, is another inspiring example of how local communities have implemented their own innovative conservation strategies to sustain fisheries income even during the lean dry season. Typically, during the rainy season, there is a tendency for overfishing as fishermen try to maximise their catch, in apprehension of a scarcity of fish in the dry season. Additionally, with the now uncertain weather patterns, many fish die due to the reduced water levels and increased temperatures during the dry season.

To address this crisis, the Reang Penbei Tor Fisheries Community has demarcated a fisheries conservation area. This is a deeper section of the lake that retains water even during the dry season providing a refuge for fish to lay eggs. As a result, this conservation area helps maintain fish populations year-round and ensures a sustainable supply of fish during both the rainy and dry seasons. The fisheries community holds regular meetings with villagers to make important decisions regarding the management of the conservation area. This participatory approach ensures that the conservation strategies are well-supported and effectively implemented. The impact of these conservation efforts has been significant. By maintaining fish stocks throughout the year, the community has seen improved fish availability and ecosystem health. This has helped sustain the income of local fisherfolk, reducing the economic pressure during the dry season when fishing typically becomes more challenging.

Additionally, these conservation efforts have had a positive impact on local temperatures. By preserving deeper water areas, the community helps mitigate the effects of temperature fluctuations and reduces the risk of fish kills during the dry season. This contributes to a more stable ecosystem, supporting biodiversity and enhancing the resilience of the local environment to climate change impacts.

Despite these successes, challenges remain. Many fishing communities around Tonle Sap face hardships due to fluctuating water levels and environmental degradation. It is urgent that the government enforce fisheries laws more strictly and restore flooded forestland to support fishery habitats and improve community livelihoods. Meanwhile, the Reang Penbei Tor Fisheries Community exemplifies how innovative conservation strategies and community involvement can achieve precisely this sort of outcome. They have set a precedent for sustainable fishing practices and it is for the government to take note to create enabling policies that can be replicated in other regions.

THAILAND

Stolen democracy amidst unmet youth aspirations

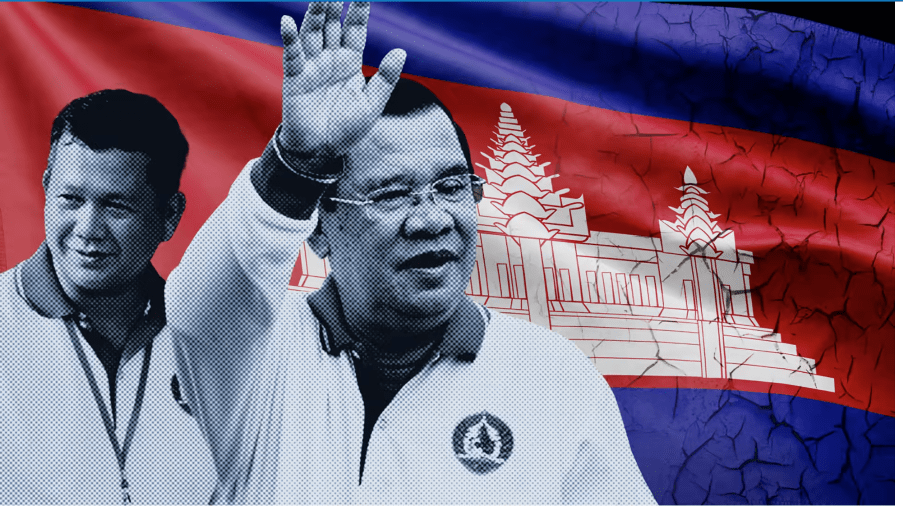

Former PM Srettha Thavisin after a few days in-office accepting the congratulatory dinner with top businesses in Thailand. 29 August 2023. (Photo @Thavisin)

The May 2023 elections in Thailand signalled new hope and optimism for the youth after a lost decade of military rule. A year after the elections, those hopes lie shattered. The winning party in the elections, the Move Forward Party (MFP) has been dissolved and its leader Pita Limjaroenrat banned from politics for 10 years. The current governing coalition in Thailand is now led by the second runner up, the Pheu Thai Party (PTP) and includes two defeated parties Bhumjaithai and United Thai Nation that have links with the previous discredited military regime.

The 2023 elections were seen as critical to usher in a new democratic politics and development model given the abysmal 10-year (2014-2023) track record of the military regime. Under the hybrid ‘capitalist-military’ government Thailand fared poorly on most key economic, socio -political and developmental indicators. Income inequality levels in Thailand are today amongst the highest in the world. With an income gini-coefficient of 43.3 percent ( zero reflects maximum equality), it tops the East Asia and Pacific (EAP) region and is the 13th most unequal of all of the countries in the world for which data is available. According to experts, government complacency, lack of a fair taxation system, unequal access to education and health and policies tailor-made to benefit the rich and powerful are to blame. The rural-urban divide is also cause for worry. In 2020, the average per capita GDP in Bangkok was more than 6.5 times that of the Isan provinces in the Northeast region, which has the lowest GDP per capita. In the same year the poverty rate was over three percentage points higher in rural areas than in urban areas with the rural poor outnumbering the urban poor by almost 2.3 million. Seventy-nine percent of the poor in Thailand are in rural areas and mainly in agricultural households.

Another disturbing indicator that could fuel further youth protests is the rising share of youth (15-24 years) who are Not in Employment, Education or Training (NEET) which has reached nearly 1.4 million or 15 percent of the population. Seventy percent of the youth who are NEET are female with most of them dropping out of school either due to pregnancy or caring responsibilities according to a 2023 study by the College of Population Studies at the Chulalongkorn University Social Research Institute (CUSRI).

Despite Thailands ‘Kitchen of the World’ media blitz, malnutrition and imbalanced diets as a result of corporate and industrial food supply chains are high. Some one million children under 14 are malnourished and there is a prevalence of 47.8 percent obesity and overweight in 2022 compared to 34.7 percent of the population in 2016.

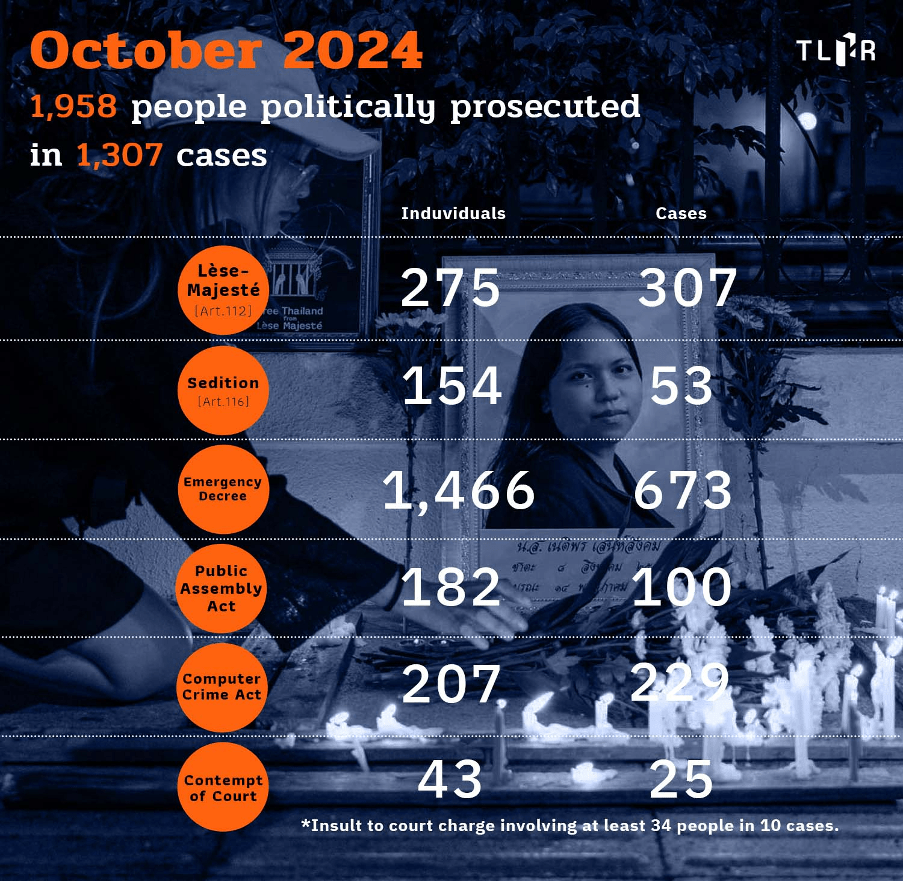

Political prosecution statistics to-date documented since the beginning of the ‘Free Youth’ protest in July 2020. 11 November 2024. (Photo: https://tlhr2014.com/en/archives/70997)

Similar to the challenge faced by peasants in the Philippines, there have been systematic attacks by the state on young activists and human rights defenders with the criminalisation of free speech. There has been rampant misuse of Article 112 (defamation), 116 (sedition) and corporations using SLAPP lawsuits to arrest activist youth. According to the public interest NGO, Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) at least 1,307 cases related to political participation and expression have been filed against 1,958 individuals since the beginning of the ‘Free Youth’ protest in July 2020 until October 2024. Among these are 217 cases against 286 children and youth under 18, based on TLHR’s statistics in February 2024. Other forms of legal oppression by the state or its apparatuses, especially those initiated and continued from the military regime include the 20-year National Plan, NGO law and SEZ law. Given that the SEZ law could bypass labour and environmental laws and even cabinet orders, the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) has issued a report citing that it comprehensively fails to protect human rights.

The so-called return of democracy has also paved the way for the strengthening of neoliberal policies such as a renewed push for Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), Foreign Direct Investment and mega projects. The ruling PTP is desperate to implement the Thailand mega project-land bridge which is said to offer a Panama Canal-like short cut for shipping in Asia. Expected to cost at least USD 28 billion, experts and environmentalists have already warned that it could be another proverbial white elephant and leave the country saddled with costly debt.

Amidst the push for environmentally damaging projects and policies, Thailand also saw extreme weather events throughout the year: 1) a record-breaking Southeast Asian heat wave affecting 77 Thai provinces (with 26 of them reaching temperatures of over 40 degrees Celsius) and leaving at least 61 people dead from conditions linked to heat stroke according to the Ministry of Public Health in May; 2) massive, extensive, and long-lasting floods caused by urban expansion, deforestation, and conversion of forests to monoculture plantations, severely inundating 44 provinces and thousands of villages in northern Thailand and directly affecting an estimated 800,000 people according to the Weekly Regional Humanitarian Snapshot by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs from September to October; and 3) the transboundary haze pollution as a consequence of corporate corn production, industrial emissions, and land use change that has worsened every year, with air pollution levels annually exceeding the World Health Organization (WHO)’s safe limits.

Civil society and activists in Thailand recognise that their role as watchdogs to hold the new regime accountable is more important than ever. There is a need to produce more compelling evidence-based research on the potential pitfalls of such large-scale projects and trade agreements and engage official spaces such as parliamentary committees with greater vigour. Given the challenging triple crises context; political, economic and environmental in Thailand, there is a lot of self-reflection and analysis especially among the youth to not repeat earlier mistakes and form united networks that can face the challenges of authoritarianism head on.

INDIA

Modi suffers electoral set back as economic crisis deepens

The June 2024 elections in which Prime Minister Modi lost his parliamentary majority was a much-needed course correction for Indian politics. In such a diverse country, parliamentary democracy thrives only when there is adequate representation and voices from minorities, women and working classes are reflected in policy circles. The past decade (2014-2024) in which the BJP enjoyed a brute majority in the Indian Parliament was anything but that.

The cover story in the Telegraph newspaper in India after the June 2024 parliamentary elections (photo: https://www.telegraphindia.com/)

The vote against Modi was a result of cumulative discontent over a number of unilateral policies; the anti-peasant farm laws ( which were withdrawn in December 2021 after one year of historic resistance by farmers), the anti-Muslim Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), the 2016 demonetisation policy that devastated rural India and small traders, the deregulation of labour laws that will further impoverish India’s already precarious working classes and a slew of privatisation of public infrastructure that have benefitted large corporations considered close to the Prime Minister.

Despite a media blitz by the ruling party in what was considered as the world’s most expensive election, the humbling of Modi shows the reality of the despair and hopelessness amongst the youth stemming from immense concentration of wealth at the higher echelons of society, the lack of decent jobs and rising cost of living.

The last 10 years have seen a historic rise in inequality in India. India’s top 1 percent income and wealth shares are at 22.6 percent and 40.1 percent of the total which are among the highest in the world, higher than South Africa, Brazil and the United States. The economist Thomas Piketty et al in a recent paper describe the situation as a new ‘Billionaire Raj’ in which India’s modern bourgeoisie aided by the Indian state oversees a society more unequal than during British colonialism. The obscenity of India’s rich in which one wedding can cost upwards of USD 600 million is to be contrasted with the sad reality that more than two-thirds of India’s population (over 850 million people) rely on subsidised food grains through the National Food Security Act (NFSA).

The triple strike of demonetisation (2016), the hasty implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (2017) and COVID-19 Pandemic (2020) were major recent events that adversely impacted the unemployment rate in India. A July 2024 report by India Ratings, a research group, estimates that a staggering 16 million jobs were lost in this period from 2016-2023. These recent shocks notwithstanding, the inability of the Indian economy to generate decent jobs for the millions of youth entering the job market every year has been an Achilles heel since the initiation of liberalisation policies in the 1990s. Latest figures show that the unemployment rate rose sharply to 9.2 percent in June 2024 from 7 percent in May 2024. An additional reason for serious concern is India’s abysmal female workforce participation rate which is amongst the lowest globally (157 out of 178). As per the Periodic Labour Force Survey for 2022-23, the labour force participation rate among women with secondary education or higher was at 29.2% which is less than half of the corresponding figure for men (73.1%). Being one of the world’s most populous nations with a diverse and young workforce, unemployment is a ticking time bomb that the Government can’t mask for too long.

An important manifestation of the employment challenge in India is the phenomenon of premature deindustrialisation – in which there is a sustainable decline in the share of output and employment in the manufacturing sector even before industrial development has been achieved. The manufacturing sectors share in employment in 2012 was just 12.5% which is amongst the lowest in industrialising countries. In 2021 it fell further to 11.3%. The other side of this story is rising import dependence on China in critical inputs such as fertilisers, active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) and electronics equipment. Predictably Indian manufacturing continues to be sluggish and given its rising import dependence many foreign companies that were earlier manufacturing in the country have left such as Ford, General Motors and Holcim.

The bizarre response from the government to the unemployment and industrialisation challenges has been to enact a series of new labour codes, in the hope that it will spur foreign investment and boost productivity to revitalise Indian industry. In September 2020, 29 labour laws in the country were arbitrarily repealed without any consultation with labour unions or state governments and were sought to be replaced with 4 labour codes; 1) code on wages, 2) code on industrial relations 3) code on occupational safety, health and working conditions, 4) code on social security.

Trade unions believe this will leave India’s already precarious workers worse off. They assert that these codes eliminate almost all internationally recognised statutory entitlements recognised by agencies such as the International Labour Organisation. This includes rights on well defined working conditions, living minimum wages, decent working hours, social security along with the right to organise, the right to strike and right to collective bargaining. Since 2020, both formal and informal sector unions across the country have been steadfastly opposing the implementation of the codes. The unions have been using precisely the tactics that will not be allowed if the labour codes are operationalised.

In November 2020, less than 2 months after the codes were passed in the Parliament, 10 national unions and affiliates across various states launched a coordinated national strike which saw the participation of over 250 million workers. This was claimed as perhaps the largest labour strike in world history. This was repeated in 2022 in which more than 200 million workers joined a two day nationwide strike under the banner of ‘ Save the people and save the nation’. On September 23, 2024, the joint platform of central unions organised a ‘black day’ against the Modi Government demanding the withdrawal of the anti-worker labour codes. Protest marches were held across the country. As a result of this resistance from workers, so far, the Government has not been able to notify these codes for implementation.

Trade union activists block trains during the 2020 national labour strike (photo: https://peoplesdispatch.org/)

Attempts by some states such as Karnataka and Tamil Nadu that tried to increase the working hours upto 12 hours were met with stiff resistance by labour unions and opposition parties. Both states are now on the backfoot due to rising protests. The Modi Government has now begun efforts to negotiate with unions to implement the codes. The Unions are not giving an inch and are demanding that the anti-labour codes be buried lock, stock and barrel.

The track record shows that coalition governments in India are more democratic, accountable and sensitive to protests and India’s federal democracy in which states have policy autonomy. It remains to be seen if the current National Democratic Alliance (NDA) Government, in which the BJP is by far the dominant party, will imply any changes in policy direction.

On the foreign policy and trade front, the prevailing uncertainty and flux in geopolitics has tempered the Modi Government’s propensity to deepen the strategic relationship with the United States and western interests.To protect its national interest and role as as a key voice of the developing world, it has had to maintain a delicate balance in terms of continuing its relationship with Russia and China.

For example, in November 2019, Prime Minister Modi took the decision to remove India from the RCEP mega trade agreement citing concerns about rising imports from China. He then chose to align India with the US created anti-China trade bloc called the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) even as the US has consistently attacked India’s trade policy on tariffs, agriculture subsidies and intellectual property at the World Trade Organisation (WTO). But despite its commitment to IPEF, India continues to participate actively in the BRICS which purports to challenge the economic, trade and finance hegemony of the west. At the latest BRICS October 2024 summit in Kazan, the bloc launched new initiatives such as BRICSpay, BRICSbridge and BRICSclear all which are intended to challenge the dominance of the US dollar and western payment systems such as SWIFT. Whether these projects mount a real challenge to dollar dominance remains to be seen but the reaction was swift. Incoming US President Donald Trump immediately responded threatening India and other BRICS countries with 100% tariffs and other sanctions if they attempted to subvert the dollar. Lastly, despite the threat of sanctions arising out of its invasion of Ukraine, India’s relationship with Russia has strengthened on multiple fronts. Russia is today the largest supplier of crude oil to India, accounting for over 35% of imports.

CONCLUSION

It is evident from these updates that the authoritarian and corporate threat to democracy in these four countries has only grown in recent years. In addition, geopolitical developments over the past few months will be a double-edged sword for the South. As Walden Bello elaborates, the comprehensive victory of Donald Trump in the US elections will result in a jettisoning of the liberal internationalism of the Democrats to be replaced by selective engagement. This could mean the abandoning of free trade, both at the WTO and bilateral free trade arenas, providing the policy space for countries of the South to forge their own trade, finance and industrial strategies. This is where recent BRICS initiatives towards de-dollarisation hold promise.

On climate, as the finance outcomes from the just concluded UN Conference of Parties (COP) in Baku in November 2024 have shown, the multilateral process is not fit for purpose. While expert predictions from bodies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) point to an exponential increase in devastating climate impacts, developing countries have been left severely under-resourced to meet the challenges of mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage even after 29 years of multilateral negotiations.The negative consequences of Trump heading up the next administration cannot be underestimated. On the other hand, a brazen denialist’s coming to power in the US may well be the trigger that will prompt the rest of the world to take those radical steps necessary to ward off climate catastrophe in the next few decades, leading to Trump and the fossil fuel lobbies being isolated within the United States itself.

RAINBOW MOVEMENT OF MOVEMENTS. Workers, farmers, peasants, fisherfolk, forest peoples, trade unions, social movements, women’s organisations, LGBTQIA+ organisations, Indigenous peoples, Dalits, ethnic organisations, cultural workers, artists, civil society organisations, and students converged and marched together in solidarity at the WSF. 2024 February 15. Pradashani Marg, Kathmandu, Nepal. Photo by Galileo de Guzman Castillo.

Despite these multiple challenges, movements and grassroots initiatives are active in all these countries exposing and challenging the powerful and elites. There is a recognition that while national initiatives and struggles at addressing the political, ecological, social and economic crises are critical, building Asia wide internationalism and solidarity is as important to dismantle transnational networks of capitalism and right-wing ideologies. After two decades, in February 2024, the World Social Forum was held in Asia in Kathmandu, Nepal. An incredible 50,000 people and more than 1,400 movements and organisations showed up from over 90 countries to exchange ideas, experiences and strategies towards generating alternatives to neoliberalism. There are now plans to host an Asia Pacific Social Forum in 2025. As Asia ‘rises’, its young and energetic social movements are also stepping up to challenge the status quo and show that alternatives are possible.

(BUILDING) ANOTHER WORLD IS POSSIBLE. The World Social Forum (WSF)—long held as an open space for the free and horizontal exchange of ideas, experiences, and strategies oriented toward enacting and generating alternatives to neoliberalism—took place in Asia after nearly two decades, at what is a critical inflection point for the peoples of the Global South. Bhrikuti Mandap Park, Kathmandu, Nepal. 2024 February 15. Photo by Galileo de Guzman Castillo.

——

[i] The RCEP is a free trade agreement (FTA) among the Asia-Pacific countries of Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam

[ii] The IPEF is an economic initiative that includes Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Fiji, India, Indonesia, Japan, Republic of Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, the United States and Vietnam

[iii] for more on the unravelling of the opportunistic alliance between Marcos-Duterte dynasties see paper by : https://focusweb.org/publications/the-marcos-duterte-dynastic-regime-in-the-philippines-how-long-will-it-last/

[iv] for more analysis on Cambodia and dynastic rule see ( 2023) New Face, Same Old System: Special Report on the Generational Transmission of Power in Cambodia published by ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights. – https://aseanmp.org/publications/post/new-face-same-old-system-special-report-on-the-generational-transmission-of-power-in-cambodia/

[v] for more analysis on the Thailand elections and aftermath see this analysis by Walden Bello and Kheetanat Synth Wannaboworn –https://focusweb.org/back-from-the-future-coalition-set-to-govern-thailand/

[vi] for more analysis on Cambodia and dynastic rule see ( 2023) New Face, Same Old System: Special Report on the Generational Transmission of Power in Cambodia published by ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights. – https://aseanmp.org/publications/post/new-face-same-old-system-special-report-on-the-generational-transmission-of-power-in-cambodia/