By Walden Bello*

(Speech at the opening plenary of the People’s Summit, Sapporo Convention Center, Hokkaido, Japan, July 6, 2008.)

The Group of Eight came into being in 1975 as the G7 at a time that the world was embroiled in deep economic crisis, much like today. Its main aim was to coordinate the macroeconomic policies of the rich countries at a time of stagflation as well as to forge a common strategy vis-a-vis the developing world, which had loosened its political and economic dependency on the First World during the heady days of decolonization, national liberation struggles, and the emergence of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) as an economic power.

See the Media Advisory: World Bank Casts its Dark Shadow Over G8

See also Walden’s article Japan Follows Singapore in Dealing with Foreign Activists

Read the call to Join the International People’s Solidarity Days: 4-8 July 2008, Hokkaido Japan

The G7 were not successful in coordinating their policies, with the US under Ronald Reagan aggressively pursuing a cheap dollar policy that brought on recession in Germany and Japan. They did, however, come together in a united front against the developing countries, putting their weight behind the neoliberal structural adjustment policies imposed by the World Bank and IMF on more than 90 developing and transition (post-socialist) economies. The structural adjustment programs rolled back the economic gains achieved by the South in the 1950’s and 1960’s.

In the 1990’s, the G7 became the main promoters of corporate-driven globalization, for which the road had been paved by the radical deregulation, radical liberalization, and radical privatization that took place in developing countries under structural adjustment. The G7 also provided strong support for the World Trade Organization (WTO) as the main agency for the process global trade and investment liberalization demanded by their corporations.

The late 1990’s, however, brought about, not the increasing prosperity for all promised by neoliberal, pro-market policies but rising absolute poverty, increasing inequality, and the consolidation of economic stagnation in the South. The collapse of the third ministerial of the WTO in Seattle in December 1999 marked the achievement of a critical mass by the forces of opposition created by the contradictions of globalization.

With the realities of globalization exposed, the summits of the G7—now G8 with the incorporation of Russia—became a lightning rod for the rising global opposition. At the G8 Summit in Genoa in June 2001, three hundred thousand people came together under the uncompromising program of “No to the G8.” The battle lines were clearly drawn, with the Italian police or carabineri contributing immensely to polarization by erupting in a riot that took the life of one activist and injured scores of others.

Elements within the G8 realized that the image of being a hegemonic directorate of globalization was not good for the future of the body. Led by the New Labor government of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown in Britain, the G8 underwent a facelift. A new discourse was forged, the key substantive elements of which were debt forgiveness for the poorest countries, the raising of aid levels to 0.7 per cent of the GDP of the G8 countries, a massive aid package for Africa, making trade serve development, and tackling climate change. The new watchwords when it came to process were “partnership,” “consultation,” “global social integration,” and the “millennium development goals.” The battle was for the soul of global civil society. The high point of this new look was the Gleneagles Summit in 2005, which was choreographed by an alliance between the Labor Government, entertainment superstars Bob Geldof and Bono, and influential British NGO’s. Several hundred thousand people who journeyed to Scotland found themselves manipulated into becoming a chorus for the glittering Aid for Africa concerts that were staged simultaneously in different parts of the globe.

By the time 2007 came along, the glitter was gone. The idea of global civil society partnering with the G8 had soured as none of the G8 governments reached the 0.7 of GDP target, aid to Africa fell short of the $20 billion promised at Gleneagles, the “Doha Development Round” had become a big joke, and serious action on climate was nowhere to be seen. Instead, the G8 communique at the Heiligendamm or Rostock Summit emphasized techno-fixes for climate change, lectured developing countries about not restricting investment by transnational corporations, and issued a thinly veiled warning about China getting preferential access to raw materials in Africa. Under the leadership of civil society in Germany, militant denunciation and confrontation of the G8 was the preferred civil society response, with thousands of demonstrators trying to penetrate the site of the leaders’ meeting to shut it down. With the dominant cry being “G8—Get out of the way,” the Heiligendamm protests retrieved the militant tradition of Genoa that had been suppressed at Gleneagles.

So we come to the G8 Summit here in Hokkaido, Japan. We have not only in Bush, Sarkozy, Brown, and Fukuda a group of discredited leaders with very low ratings at the polls in their own countries. We have as well a G8 that is, more than ever, lacking in legitimacy as the typhoon unleashed by the project of globalization that it has promoted is wracking the globe in the form of the simultaneous crises of skyrocketing oil prices, rising food prices, global financial collapse, and worsening climate change. Against this backdrop, Japanese and Asian social movements are faced with the choice of taking either the Road of Genoa or the Road of Gleneagles—that is, to deepen the G8’s crisis of legitimacy or, as in Gleneagles, to salvage the G8 once again. The greatest gift that the Japanese movement can give to global civil society is by leading the struggle to make the Hokkaido Summit the final summit of the G8.

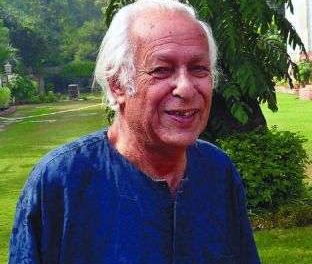

*Walden Bello is president of the Freedom from Debt Coalition and senior analyst of Focus on the Global South.