Read the rest of the series at focusweb.org/tag/kaa70.

by Salsabila Putri Noor Aziziah*

Progressive struggles around the world have been masked by the mainstream narrative of the Global North countries’ victory following World War II. It is not easy to curate and recollect memories of past anti-imperialist movements, including one led by feminists transnationally. The spirit of the anti-imperialist movement led by women had emerged even before the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) of 1955 in Bandung. While the Bandung Conference was led by national leaders of African and Asian nations, these feminist movements were led by unheard feminist leaders across the world aligned with the spirit of solidarity and anti-imperialism.

In looking at global history, feminists often question: where were the women? What barriers did they face in the world of diplomacy? What were their struggles in post-World War II reality? What narratives did they bring about? These are critical points to be discussed further to unmask memories of feminist movements against imperialist power. One important aspect to note from the feminist anti-imperialist movement is that their struggle was not only against imperial state power, but it was also a different strand the international feminist movement, where women of colonized nations consolidated their power to reject the Western-dominated feminist agenda and develop South-South solidarity based on their commonality.[i] Thus, women were important actors in shaping the anti-imperialist movement, and the Bandung Conference was a formative moment for the internationalist feminist movement in the Global South.

Unfortunately, this monumental history of progressive feminist movements against imperialism has been poorly documented and remains scattered, limiting its access to scholars and the public. This article is an effort to unmask the memories of women surrounding the Bandung Conference that highlights several dimensions (1) imperialism as a women’s issue; (2) women’s anti-imperialist efforts prior to the Bandung Conference; and (3) post-Bandung women’s movements.

Imperialism as a Women’s Issue

At that time, the internationalist feminist movement of Asia featured three interlinking strands of feminist analysis and activism. The first strand focused on social reform feminism, where women sought to improve access to education, health care, social welfare, and modern cultural and religious practices. This strand emerged within colonized societies to push the shift in social relations of gender. The second strand consisted of nationalist and state feminism that looked for equal rights of women in independent nations and full participation of women in public life. Lastly, the least discussed strand of feminism was the leftist, mass-based feminism that sought to restructure the economy, social relations, and political practices that disenfranchised women. The second and third strands were heavily intertwined in newly independent Asian nations, as both shared a common commitment to women’s legal and state-based inclusion. However, leftist feminism departed from nationalist and state feminism to continue demanding transformation in relations of production and reproduction against the newly inaugurated government.

Asian and African women were at the forefront of making interventions within the feminist movement to highlight their struggle against imperialism. During the Congress of Women’s International Democratic Federation[ii] (WIDF), delegates from Asia and Africa redefined fascism from the perspective of imperialism. They reminded the organization that fascism was a powerful force behind military conflict but colonialism was another, as colonial powers withheld freedom from their colonies. By focusing on the political economy of colonialism, they emphasized the loss of opportunity to enjoy basic dignity and well-being of the colonized people.[iii] At that time, women realized that the fabric of their daily problems stemmed from the intersection of the systems of colonialism, fascism, and patriarchy.[iv] Thus, the need to form a mass-based transnational women’s movement that fought these systems simultaneously became urgent.

However, their advocacy did not end after the formal independence of their nations. In fact, there were at least two factors that impeded the full promise of self-determination. The first factor was military and economic coercion of imperial powers, which made land reform and nationalization policies difficult to implement. This was mainly characterized by financial capitalism and US imperialism. The second factor was the national structure of propertied classes and business lobbies that hindered nations from creating meaningful economic reform. These two factors were mutually reinforcing, as the colonial forms of industrial ownership continued under the newly formed government. In the face of these problems, women’s movements continued to raise issues of endemic inequities created within the capitalist class system. Whether under a colonial or independent state, they demanded a change in national priorities for poor, working-class, and middle-class women.

This momentum also marked an attempt to withdraw from the charity model of feminist transnationalism to an embrace of a solidarity approach.[v] There were two characteristics of solidarity: (1) a solidarity of commonality and (2) a solidarity of complicity. A solidarity of commonality referred to a universal women’s human rights agenda that invoked shared values and goals that would benefit women across the world. In contrast, a solidarity to end complicity responded to different power relations between women based on their class, nation, or ethnicity. This resulted in unequal benefits and negative effects. Therefore, solidarity against complicity meant holding colonized and colonizing nations responsible for the atrocities they carried out in their nation’s name or by their nation’s people. There was also a push for Western women to fight against their own complicity with imperialism by embedding anticolonial struggles in their national work.

Women’s Anti-Imperialist Conferences Leading Up to Bandung

The Asia – Africa Conference (Bandung Conference) of 1955 was held in Bandung, Indonesia as the culmination of a non-aligned and anti-imperialist movement. But in order to highlight the feminist struggles against colonialism, it is important to look into the events leading up to the Bandung Conference. One early momentum to be documented as part of the Pan-Asian women’s movement was the Asian Relations Conference[vi] of 1947, hosted by the Indian Council of World Affairs in New Delhi. The aim was to provide a cultural and intellectual revival and social progress in Asia, independent of all questions of internal as well as international politics. The Conference was claimed to be “non-political” as there was no communique or resolution to put pressure on the Government, but there were important topics being discussed. There were eight topics covered in the Conference, including national movement for freedom; racial problems; migration; transition from colonial to national economy; agricultural reconstruction and industrial development; labor and social services; cultural problems; status of women and women’s movement. Working groups formed around these topics.

Jawaharlal Nehru, as the leader of the transitional government in India, was present at the Conference to welcome delegates, encouraging them despite the tumultuous political and social change of their respective countries. The Asian Relations Conference was attended by women from twelve Asian nations who participated in the Status of Women and Women’s Movement group. Among them were important figures such as Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, an Indian social reformer and freedom fighter. By the end of the Conference, the Women’s Group called for (1) organized efforts to promote the education, social, political, and economic interests of the people, particularly the poor; (2) removal of all inequalities, restrictions and disabilities imposed upon women by virtue of custom, religion, or law; (3) acknowledgment of the pressing need to improve the “tragically low percentage of literacy […] among women in the majority of Eastern countries,” and addressing the need for the immediate introduction of free, basic education on a universal scale; (4) legally implemented more equitable property, marriage, and divorce laws for women.[vii] After the discussion, the group voted in favor of reviving the All Asian Women’s Conference.[viii]

Following the Asian Relations Conference, three members of WIDF—Jaikishore Handoo from India, Vivian Carter Mason from the United States, and Jeanne Merens from Algeria—published a report on racism and colonial oppression titled “The Women of Asia and Africa.” This report highlighted the shared struggles against colonialism in Asia and Africa. It was a stepping stone to prepare for the Asian Women’s Conference. The latter was planned to be held in India; however, WIDF delegates realized that it was difficult to draw in support from Indian officials. The objections toward the conference in India at that time represented a shift from cross-border solidarity to what was called nationalist individualism.[ix]

Sarojini Naidu, a nationalist leader at that time, stated, “At the present time I see no necessity for the functioning of women’s organizations.” Others, such as Renuka Ray, a member of the Indian Constituent Assembly, felt the conference would be a threat to the fragile new government and that it might destabilize Nehru’s and the Congress Party’s political position. Euro-American pressure on Nehru and his government’s distrust of Indian communism finally undermined the plan to host the Asian Women’s Conference in Kolkata.

Nevertheless, Indian communist women activists held an all-Indian conference that involved regional leftist women’s groups and allied organizations for workers and peasants. This conference then became the seed that led to the establishment of a revolutionary women’s organization called the National Federation of Indian Women (NFIW).

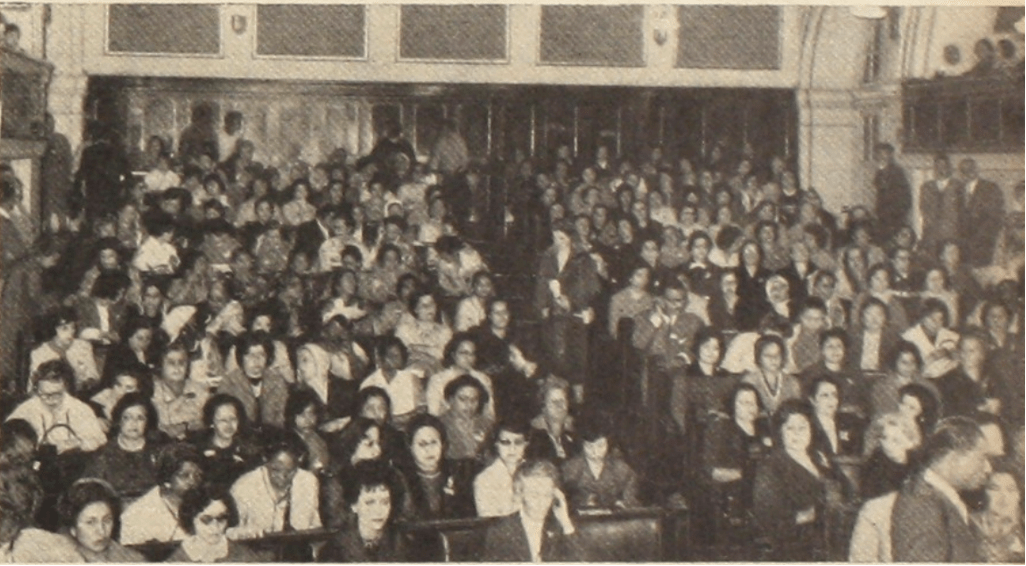

Image 1. Asian Women’s Conference in Beijing 1949.[x]

Image 1. Asian Women’s Conference in Beijing 1949.[x]

One of the most important women’s conferences prior to the Bandung Conference was the Asian Women’s Conference (AWC), held in 1949 in Beijing, China, and hosted by WIDF and the All China Women’s Democratic Federation. The Conference drew 367 women from 37 countries[xi], marking it as the emergence of an international women’s movement committed to building a left-oriented mass-base and revolutionary women’s movement. AWC derived its framework from the communist and left traditions of organizing and Marxist-Leninist theory. They organized peasant and rural women instead of women from metropolitan centers, as rural women were the main source of colonial extraction in the Global South.

In her speech Chinese leader Soong Ching Ling addressed the common enemies of women—foreign imperialism, which resulted in colonialism, and home-grown feudalism.[xii] She also encouraged women of Asia to be the leaders of their own liberation, as they could not expect sympathy from the imperialists. There were a few points that she concluded were important rights to be fulfilled, including:

- Equal rights of women in marriage;

- All rights in the family and in inheritance equal to men;

- The rights of mothers to their children;

- Child-care through increased creches, nurseries, kindergartens, sanitation facilities and education in personal hygiene;

- Legislation providing equal pay for equal work, maternity leave with full pay and outlawing of child labor;

- Compulsory free education for all children and the spread of the teachers’ movement to wipe out illiteracy;

- Funds for higher education for women.

During the Conference, Indonesian leader Lillah Suripno pushed for anti-imperialist wording to be explicitly stated and not merely “peace.” However, it was agreed that peace in this context was strategically anti-imperialist. Women in colonized states were the leading force of the fight against imperialism, while their supporters in colonizing countries used their power to block the export of imperialist weaponry and logistics. The conference was the culmination of efforts in merging the women’s movement in China and Asia with the global socialist women’s movement.

Women’s Movement Continuing the Bandung Spirit

The Bandung Conference of 1955 was attended by Asian and African leaders who later formed the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) based on the 10 points of the Bandung Declaration. It is worth noting that while the Declaration stated full support of United Nations Charter principles, it did not explicitly mention women’s rights. Nonetheless, the momentum of the Bandung Conference further strengthened feminists in the Global South and Global North to look at women’s and girls’ issues using a structural approach. Race, colonialism, and economic inequality were central to the agenda of the women’s movement at that time.

NAM, as an attempt to collectively conceive a community of nations in the Global South, was formulated on clear political and ideological lines.[xiii] This idea of newly liberated countries demanding that their agency and voice be recognized aligned with women’s movements around the world which demanded that women not be treated as passive victims but seen as as active subjects and recognized for their steadfastness in resisting oppression.

Following the 1949 Asian Women’s Conference in Beijing, solidarity within the women’s movement broadened and brought together women from Asia and Africa to Colombo in 1958. The Asian-African Women’s Conference was hosted from February 15–24, 1958, supported by five Asian women’s organizations: the All Ceylon Women’s Conference (ACWC), Women’s Welfare League from Burma, the Kongress Wanita Indonesia (Indonesia Women’s Congress/KOWANI), the All Pakistan Women’s Association, and the All India Women’s Commission (AIWC). All of these organizations had committed to improving women’s education as well as access to health care and social development. Although they had a long tradition of social reform feminism, they also used nationalist and state feminist analysis to push for women’s interests in the governance of their independent nations.

The Asian-African Women’s Conference invoked a similar Non-Aligned Movement spirit following the Bandung Conference. There were at least six common concerns[xiv] discussed at the conference: (1) health problems that included maternity and child welfare, family welfare services, training of health personnel; (2) educational concerns including access of women and girls to equal educational opportunities, social and fundamental education, and vocational education; (3) women’s citizenship problems that covered franchise, voting rights, and opportunities to participate in public life including the UN; (4) slavery and trafficking of women and girls; (5) labor problems such as labor exploitation, child labor, hazardous occupations, and labor welfare; (6) promotion of cultural, social, and economic cooperation between the Asian and African regions in the context of world peace.

Indian deputy foreign minister and lead delegate at that time, Lakshmi Menon, underlined the importance of tackling illegal trafficking of women and girls in Asia and Africa—Menon stated that it had only been solved in Communist countries, as other countries’ attitudes were only perpetuating it.[xv] In the presence of UN agencies as observers, Chinese women walked out of three plenary sessions in protest of their country’s exclusion from the UN. This space was not only a site where women exchanged experiences but also where they demanded their recognition.

In the lead-up to the second Asian-African Women’s Conference, there was a debate about whether or not it was important to create an organizational body, pushed by India’s AIWC. Ezlynn Deraniyagala, President of ACWC at that time, conveyed her disagreement by describing the Conference in Colombo as still an early step for women of Asia and Africa to break down geographical barriers, build sisterhood, and work together transnationally.

Image 2. Afro-Asian Women’s Conference in Cairo.[xvi]

Eventually, a decision was made to host the Afro-Asian Women’s Conference in Cairo in 1961. This conference was hosted by the Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organisation (AAPSO)[xvii] inviting state feminists and leftist feminists linked to NAM. A total of 247 women from 50 countries, including 36 official delegations and 6 individual observers, were present at the 1961 Cairo Conference. The aim was to discuss the path for women’s emancipation and encourage national liberation in Asia and Africa. The demand from the 1961 Cairo Conference was to push for an energized, progressive state and activist legal systems. The Afro-Asian Women’s Conference involved nationalist feminists, state feminists, and also left-wing and revolutionary feminists such as Hajrah Begum.[xviii] This conference was also directly linked to the Bandung Conference and the Third World project.

Image 3. Afro-Asian Women’s Conference banner in Cairo.[xix]

Image 3. Afro-Asian Women’s Conference banner in Cairo.[xix]

Women were not only present in the hall but also at the podium of the Afro-Asian Women’s Conference. Indian social activist Nameshwari Nehru gave her speech, while Aisha Abdul-Rahman, a renowned Egyptian journalist and anti-Nasser feminist, was also recorded. At the conference, it was discussed that imperialism confined emancipation; therefore, liberation was the first step for women to seize their places in society. This also led to a more coherent agenda to highlight the role of women in national liberation movements. The 1961 Afro-Asian Women’s Conference’s final recommendations included issues such as marriage rights, equality in the economic field—from equal pay and distribution of land to vocational training—and inclusive policy prescriptions for women who did not work for a wage.[xx]

NAM and Bandung legacy in recent feminist movements

The early days of the Bandung Conference and the women’s movement conferences surrounding it represented the interconnecting and internationalist nature of the movement in Asia and Africa. It is important to underline the larger context of the Cold War in which these conferences took place. Anti-communist suppression was rampant at that time, particularly against left-wing women’s movements. This then resulted in the suppression of memory. The history of the women’s movement in relation to the Non-Aligned Movement was also dominated by the contributions of left-wing and socialist women’s organizations. The bias against archiving these opinions by the prevailing anti-communist atmosphere made it difficult to discover memories, archives, and records of their meetings.

Indian organizations such as NFIW had been burning records every five years for their security, but they also kept documents regionally in households instead of centralizing them at the national level. On top of that, the outcomes of these conferences were not well advertised. It may have seemed that the conference appeals and discussions were not disseminated widely. However, they were spread widely in left-wing presses and gatherings. Many of these memories exist in the form of oral histories and have been transcribed to be stored in museums.

At a time when the US and Soviet Union (USSR) were busy segmenting the world to create blocs, NAM emerged as a multilateral forum and political entity led by newly liberated nations to reject great power politics. The grouping was not meant to create a different bloc from the existing ones, but it had clear political and ideological lines. Its basic elements lay in its approach to the struggle against imperialism and neo-colonialism, as well as moderation in relations with all big powers.[xxi]

While there was no explicit reference to women, gender, or women’s rights in the Bandung Declaration, it continued to affect women’s movements in the following years. Feminists of the Global South and Global North took a structural approach in addressing issues of women and girls by being cognizant of race, colonialism, and economic inequality. With the spirit of NAM, feminists also challenged the definition of the UN Charter. In the beginning, the UN viewed “women’s issues” as a social development issue instead of connecting it with the larger international development agenda. On top of that, women from the Global South asserted their agency in contributing to their countries, not merely as receivers of social services.[xxii] NAM in 1981 also underlined the global economic impacts on women, drawing from cases of harmful practices conducted by multinational corporations on women in both developing and developed countries. NAM then became an imagined community of Third World struggles where women from different histories and locations came together in opposition to all forms of systemic domination.[xxiii]

The dynamics, however, have fundamentally changed today. Globalization and economic liberalization have been rampant since the inception of neoliberalism in the 1980s. Countries in the Global South have faced multiple crises that deepen poverty and inequality. We are also facing a rush in regional and bilateral trade agreements where liberalization and privatization have become key agendas that affect the lives of people. Women’s rights are heavily co-opted by neoliberal interests to integrate women into the global capitalist system, where a few women control the means of production and the majority face exploitation. The women’s movement of today is not only challenged by external factors such as the rise of militarism, capitalism, and patriarchy but also internally, pushing it to take a broader approach in addressing the issues faced by women.

There is a need for the global women’s movement to look at the root causes of gender-based violence and discrimination against women. It must not limit its analysis to the question of identity and representation but also examine the structural socioeconomic factors that prevent women from fulfilling their rights. Moreover, with emerging initiatives such as South-South Cooperation, the women’s movement must take a critical approach in ensuring that the agenda is not brushed by the same neoliberal interests but represents a truly just and equal international cooperation based on solidarity among nations.

*Salsabila Noor Aziziah is a researcher from Puanifesto, a feminist collective from Indonesia, grounded in a decolonial lens, and part of both the Indonesian Civil Society Coalition for Economic Justice and the Gender and Trade Coalition.

____

[i] Laura Bier, Revolutionary Womanhood: Feminisms, Modernity, and the State in Nasser’s Egypt (Stanford University Press, 2011): 161.

[ii] Women’s International Democratic Federation (WIDF) was formed in Paris 1945. WIDF is an anti-fascist women’s organization involving women globally. Their intent was to combat racist and sexist ideology of fascist regimes. Yulia Gradskova, The Women’s International Democratic Federation, the Global South and the Cold War Defending the Rights of Women of the ‘Whole World’? (Routledge, 2022).

[iii] Elisabeth Armstrong, “Before Bandung: The Anti-Imperialist Women’s Movement in Asia and the Women’s International Democratic Federation,” Study of Women and Gender Faculty Publication, Smith College (2016): 321.

[iv] Elisabeth Armstrong, “Peace and the Barrel of the Gun in theInternationalist Women’s Movement, 1945–49, Meridian, Vol. 18, No. 2 (2019): 262.

[v] “Blog: The HERstory of South-South Cooperation: International Women’s Day,” March 8, 2021. https://southsouth-galaxy.org/blog/the-herstory-of-south-south-cooperation/ accessed on Febrary 28, 2025.

[vi] J. A. McCallum, “The Asian Relations Conference,” The Australian Quarterly Vol. 19, No. 2 (1947): 13.

[vii] Garima Karia, “Forgotten Femissaries: Women’s Diplomacy in the Afro-Asian World (1945-1975)” McGill University, https://www.mcgill.ca/arts-internships/files/arts-internships/aria_final_poster_garima_karia.pdf accessed on February 28, 2025.

[viii] The first All Asian Women’s Conference (AAWC) was held in Lahore 1931. It was an attempt to create a regular space to forge a Pan-Asian women’s movement. Sumita Mukherjee, “The All-Asian Women’s Conference 1931: Indian women and their leadership of a pan-Asian feminist organisation,” Women’s History Review, Vol. 26, No. 3 (2017): 363. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09612025.2016.1163924

[ix] Elisabeth Armstrong, “Before Bandung: The Anti-Imperialist Women’s Movement in Asia and the Women’s International Democratic Federation,” Study of Women and Gender Faculty Publication, Smith College (2016): 315.

[x] UC Press, “Decolonization is Women’s Work,” UC Press Blog, March 8, 2023 https://www.ucpress.edu/blog-posts/61798-decolonization-is-womens-work accessed on March 3, 2025.

[xi] Garima Karia, “Forgotten Femissaries: Women’s Diplomacy in the Afro-Asian World (1945-1975)” McGill University, https://www.mcgill.ca/arts-internships/files/arts-internships/aria_final_poster_garima_karia.pdf accessed on February 28, 2025.

[xii] Soong Ching Ling, “Speech to the Asian Women’s Conference (Peking, December 11, 1949)” Chinese Studies in History Vol. 5, No. 4 (1972): 246.

[xiii] Devaki Jain & Shubha Chacko, “Walking together: the journey of the Non-Aligned Movement and the women’s movement,” Development in Practice, Vol. 19, No. 7 (2009): 896.

[xiv] Asian-African Conference of Women 1957-61, https://compass.fivecolleges.edu/islandora/object/smith:1359476 accessed on March 5, 2025.

[xv] Garima Karia, “Forgotten Femissaries: Women’s Diplomacy in the Afro-Asian World (1945-1975)” McGill University, https://www.mcgill.ca/arts-internships/files/arts-internships/aria_final_poster_garima_karia.pdf accessed on March 5, 2025.

[xvi] “Afro-Asian Network Visualized” https://afroasian.mediaplaygrounds.co.uk accessed on March 10, 2025.

[xvii] AAPSO is a mass-based organization that has national committees in 90 Asian and African countries. The organization held its first conference in Cairo 1957 and is considered as a popular extension of the objectives of NAM. https://www.aapsorg.org/en/welcome-to-aapso.html accessed on March 10, 2025.

[xviii] Hajrah Begum was an office holder of WIDF in the 1950s, founder of the women’s wing of Communist Part of India, National Federation of Indian Women (NFIW). Elisabeth Armstrong, “Before Bandung: The Anti-Imperialist Women’s Movement in Asia and the Women’s International Democratic Federation,” Study of Women and Gender Faculty Publication, Smith College (2016): 317.

[xix] United Arab Republic: First Conference Of Afro-Asian Women: Big March Through Cairo (1961). https://www.britishpathe.com/asset/247832/

[xx] Garima Karia, “Forgotten Femissaries: Women’s Diplomacy in the Afro-Asian World (1945-1975)” McGill University, https://www.mcgill.ca/arts-internships/files/arts-internships/aria_final_poster_garima_karia.pdf accessed on March 5, 2025.

[xxi] Devaki Jain & Shubha Chacko, “Walking together: the journey of the Non-Aligned Movement and the women’s movement,” Development in Practice, Vol. 19, No. 7 (2009): 896.

[xxii] Aziza Ahmed, “Bandung’s Legacy: Solidarity and Contestation in Global Women’s Rights,” Bandung, Global History, and International Law: Critical Pasts and Pending Futures (Cambridge University Press, 2017): 451-452.

[xxiii] Laura Bier, “Our Sisters in Struggle: Non-Alignment, Afro-Asian Solidarity and National Identity in the Egyptian Women’s Press: 1952–1967” Working Paper No. 4, 2002.

![[CSIPM] Civil society and Indigenous Peoples’ movements gather in Rome to demand transformative policies to tackle the food crisis](https://focusweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/FesfFy2WYAAX_pd-440x264.jpeg)