Chrek Sophea blogs on current issues confronting the ACSC/APF, reflecting on what have transpired in recent preparatory meetings and on the challenges that affect the future of this regional civil society formation, including Sombath Somphone’s enforced disappearance which continues to be a major issue.

In the two recently held preparatory meetings of the ASEAN Civil Society Conference/ASEAN Peoples’ Forum (ACSC/APF) in March and May respectively, there have been no indications that the upcoming ACSC/APF, to be held in Dili, Timor-Leste in August 2016, can provide a safe space for Laos’ progressive and independent civil society organizations (CSOs)—a space where they can critique, raise concerns, and voice dissenting opinions on various issues, including human rights violations, enforced disappearance, and the negative impact of infrastructure development projects, agri-business, mega power investment projects, extractive industries, etc. on ordinary peoples’ lives. By safe, I mean that even in the presence of government-sponsored NGO representatives, the voices of these members of independent CSOs shall be heard. That they shall be allowed to organize and conduct their own panels and wouldn’t feel threatened or intimidated.

Before we go any further, let me make it clear that the above-point is made without intending to question the capability, the independence, and the activism of our comrades, brothers, and sisters in Timor-Leste. We continue to be inspired by their heroic struggles in the past for their country’s liberation. We are not trying to criticize or block the upcoming ACSC/APF from happening. The above-point is raised with greater concern for what transpired in the two previous preparatory meetings. I recall that the decision to hold the 2016 conference in Dili was a) in support of the membership of our friends in Timor-Leste and b) to give space to Lao CSOs to talk about peoples’ issues, as they would not be able to talk about human rights violations, enforced disappearance, hydropower-dams, indigenous peoples’ rights, and LGBTQ issues if the ACSC/APF were to be held in Laos. If it were, there would be no guarantee that after this event, our Laos CSOs’ friends would be safe.

In the second regional consultation meeting, which took place in Laos in May, a larger number of pro-government voices, including some of those from Cambodia and Vietnam, were brought together. Their number was more than that in the first meeting held in Bangkok. The Lao government’s presence was clearly felt in the second meeting and, as a result, dissenting views were not expressed and issues of human rights violations, enforced disappearance of human rights defenders and/or community activists, and the negative impact of hydropower-dams, and land conflicts/evictions, etc. were not raised. A rosy picture was painted of Laos as a happy nation where such issues did not exist. Meanwhile, the two representatives of the Lao National Organizing Committee (NOC), who ideally should represent Lao CSOs in the ACSC/APF, focused their presentations on the role of Lao CSOs in the past few years and made direct criticisms of CSOs which did not play so-called constructive roles in working with the Government of Laos (GoL). Those CSOs were also accused of being government opponents and supported by outsiders. It was also saddening that Sombath Somphone, a prominent development worker, peaceful activist, and current victim of enforced disappearance, was blamed for reduced funding to Lao CSOs as a result of his enforced disappearance and the campaign for his safe return.

“In the last decade, some groups of people who have lost their economic interest and political rights have tried to use the hand of some NGOs to criticize, blame, and subvert government. It is normal that such NGOs have had to follow sponsor’s policy and such conduct is clearly revealed and disclosed to the public, consequently global NGOs have lost credibility day by day and created conflicts of opinion inside NGOs that lead to the pseudo-separation into two antagonistic groups: pro-government and anti-government,” said Dr. Maydom Chanthanisnh, chair of the Laos NOC, during his presentation.

“Laos’ CSOs have lost face because of Sombath Somphone. We have lost the financial sources from donors because of him,” said Mr. Cher Her, vice chair of Laos NOC.

“If Laos’ government accepts that we ‘CSOs’ are their friend and development partners, we can get financial support from them,” the vice-chair added.

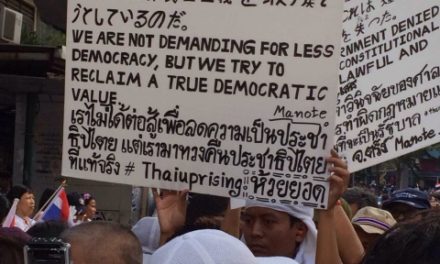

Another controversy in the ACSC/APF process is whether CSOs should engage with the ASEAN heads of states. The past interfaces have not resulted in any meaningful dialogue, commitments, or political will to address the ACSC/APF demands. At the same time, popular mobilizations such as demonstrations, peaceful protests, and other actions have also not resulted in any positive responses from the government. Therefore, the decision on how to engage with the ASEAN heads of states remains pending. An impact assessment, to be presented in Dili, has been conducted to see if past engagements have resulted in any meaningful change.

This year, when Laos holds the chairmanship of ASEAN, engagement with its heads of states will most likely go through the GoL. It is hard to believe that CSOs and peoples’ movements will have any more success in engaging with the GoL than they have had with other governments in this region. The GoL has made it clear from the beginning that if the ASEAN CSOs want to enter into dialogue with them, it has to be conducted in a respectful way, which for them means not to speak about a number of pressing issues. In the negotiation process, consensus has to be used to get both parties come into common agreement. In the case of ACSC/APF, what pressing issues do we have to remain silent on in order to reach consensus? What more do we have to give up?

An alarming reality in all ASEAN countries is the deteriorating human rights situation and rising use of the military for domestic law and order. An increasing number of human rights defenders and community activists have been jailed in Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam, and have been victims of enforced disappearance, or are facing lawsuits and attitude adjustment, while spaces for public dialogue are shrinking. But at the same time, we cannot forget that this year Laos holds the chairmanship of ASEAN and thus Laos has to be in the spotlight. The Government of Laos has to address the issues and demands of its people, which include bringing Sombath back to his family and to us, his community of CSOs. It will be unfortunate if Sombath’s case and those of other enforced disappearance cases in Laos, as well as in this region, are not brought up in the coming ACSC/APF.

“We want space, and we will struggle to get it. We will go to great lengths doing policy advocacy, fielding or supporting candidates in electoral exercises, supporting our own colleagues for appointment in official posts; aside from the usual community work, marches, and mass actions,” said Jenina Joy Chavez in her paper People and ASEAN: Defining and Divide[1].

“But we should also be mindful when protecting the space we think we have secured for ourselves. The objective is for the progressive opening up of spaces, not just for institutionalization for the sake of having a space, albeit ceremonial,” Chavez wrote.

If we believe that the ACSC/APF is a space for progressive and independent CSOs and peoples’ movements, reclaiming this space is imperative. This space should be used to bring together and unite the victims of the current crises in the political and economic systems, and to shape a peoples’ discourse around the better region that we want. #

[1] http://www.focusonpoverty.org/peoples-and-asean-defining-the-divide/

![[IN PHOTOS] In Defense of Human Rights and Dignity Movement (iDEFEND) Mobilization on the fourth State of the Nation Address (SONA) of Ferdinand Marcos, Jr.](https://focusweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/1-150x150.jpg)