“I will promote a peaceful environment for a unified society based on love, unity and compassion so that Thai people can live with stability and happiness, and I will safeguard the dignity of the institutions of State, Religion and Monarchy which are deeply cherished by the people of Thailand” (General Prayuth Chan-o-cha, during the 11 June 2019 royal appointment ceremony)

Authoritarian Renewal

General Prayuth Chan-o-cha retained his post as the Prime Minister of Thailand with a majority vote of 500 against his opponent’s 244 votes. His mandate was ushered in by 251 votes from members of parliament (MPs) and 249 votes from unelected senators, defeating Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, the head of the Future Forward Party (FFP).

The vote to finalize the official results and select the prime minister took more than two months after the general election on 24 March 2019. Official results endorsed by the Election Commission of Thailand (ECT) declared that Pheu Thai Party (PTP) gained the most number of MPs with 136 seats, followed by Palang Prachrath Party (PPRP) with 116 MPs and FFP with 81 MPs. The much-awaited transition from military rule in Thailand was made possible because the Democrat, Bhumjaithai and 16 small parties joined a 254-member PPRP-led coalition to form the government. However, the new government has a razor-thin majority which may not be stable in the long run, with parties flocking to the pro-junta coalition for political interests.

Scrambled Democracy

As elections are important in modern nation states, even the Thai junta found it unavoidable as a tool to legitimize its power for the long term. The 2019 election fulfilled such purpose for the junta, the first time after the voided election in 2014 where Thais voted to select their representatives in the parliament. Nonetheless, irregularities made it possible for the junta and its allies to win and seize power through the election.

Undeniably, the Thai junta, whose official name is the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), employed numerous political tactics as run-up steps after ousting the Yingluck Shinawatra government in the May 2014 coup. The 2017 Constitution designed election regulations and apparatus that favour the junta to maintain its power. Somsak Thepsuthin, a PPRP MP, affirmed this on 18 November 2018 saying, “In this election, the constitution was designed for us (PPRP).”

The 2017 Constitution was legitimized through a lop-sided referendum in 2016 that prohibited campaigning for “No” votes. The charter granted authority for 250 junta handpicked senators to join in selecting the prime minister. Unsurprisingly, senators cast a concerted vote for General Prayuth to be the 29th Prime Minister of Thailand. The Senate’s five-year term of office is also notably longer than the four years of the lower house of parliament, which enables this senate to vote at least twice for the Thai prime minister.

Moreover, the Constitution gives more power to the unelected bureaucratic elite to influence the direction of Thai politics, as can be seen through the actions of judiciary, army and independent organizations such as the ECT from the recent election.

The 2017 Constitution drafters introduced a unique Mixed Member Apportionment (MMA) system with the aim of deterring a landslide victory by a single party by capping the number of MPs to constituency seats. Thus, PTP was not eligible for any party-list seat after winning more constituency seats than corresponding party list shares based on the total number of votes during the election.

Even then, the PRRP-led parliamentary majority was only made possible after the ECT applied a controversial formula to change the party-list results. The formula took away seats from previous winners—for example up to 7 seats were taken from FFP—to grant one MP seat to 11 small parties. Each of these 11 parties gained less than the minimum threshold 71,000 votes for a parliament seat, as specified in the party-list calculation formula. Still, one seat for these erstwhile losing parties was an irresistible gift to easily convince them to join the pro-junta coalition. The legitimacy for the ECT’s mysterious formula was gained from a Constitution Court ruling that the MP Election Act Section 128 was not inconsistent with the 2017 Constitution Section 91 in regarding the calculation of the party-list seats. It must be noted however that the court did not rule on any specific formula. As a result, the MP seats of the anti-junta bloc—including PTP, FFP, Seree Ruam Thai Party, Prachachart Party, Puea Chat Party, Palang Puang Chon Thai Party, and New Economics Party—was decreased from 253 to 245 seats. The dubious party-list formula was the last in a series of questionable ECT actions in running the recent election to facilitate pro-junta parties to win.

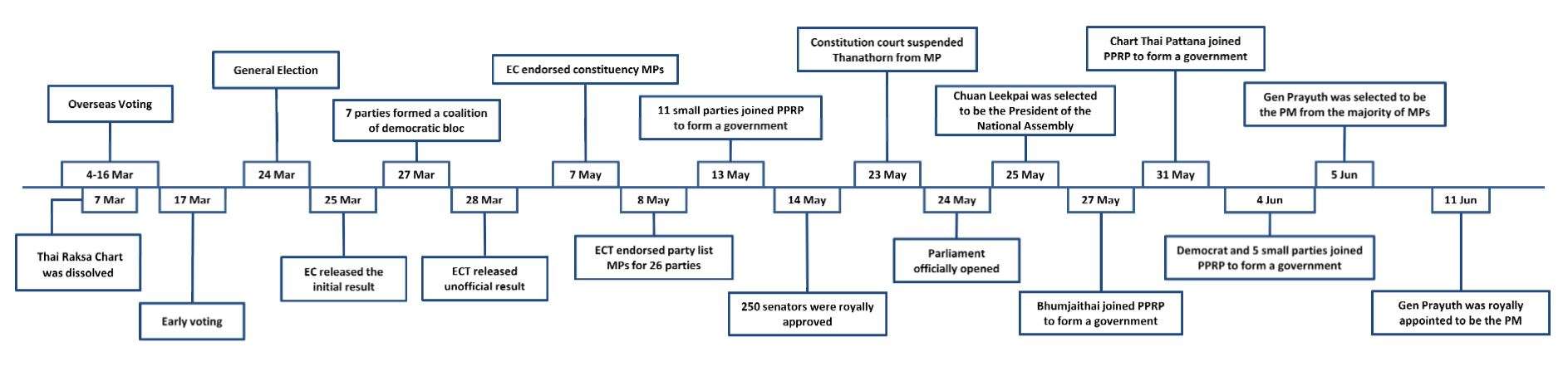

Time line of the 2019 Elections in Thailand

Compiled by the author. Please click on the image to zoom.

In addition, the junta’s allies also used all opportunities to employ judicial harassment cases to weaken if not eliminate its opponents during this election, including the dissolution of Thai Raksa Chart Party, the cybercrime case against FFP, and a sedition charge and a disqualification case against FFP head Thanathorn.

Finally, the PPRP also gained extreme advantage from the junta’s five-year grip on power by using strategic steps to be able to continue the legacy of military rule. For example, the junta built the “Pracharath” brand, using it as the name of its populist economic schemes as early as September 2015. In this way, voters recognized the name “Pracharath” long before the PPRP was founded in March 2018 and invited General Prayuth to be its PM candidate. Its victory seems to be the result of a long term plan to succeed through invented actors and mechanisms.

Welcome to the Democratic Dictatorship

“We are Thai and this is Thai democracy. You have to adapt what you have learned suitably in our country…Thai democracy is the notion of Thais love Thais and we are united.” (Thai army chief General Apirat Kongsompong, 2 April 2019)

Political rhetoric to support authoritarianism has been widespread in Thailand, and has made Thai conservatives hallucinate abouta peaceful country under a strong leader, especially led by the military. The so-called Thai-style democracy draws upon traditional values, so-called Thai-ness, demanding loyalty to three core institutions, including nation, religion and monarchy. However, this notion is based on a hierarchical social order requiring “good people” to rule the country while devaluing the principle of political equality through a free and fair electoral system. In other words, the one-person, one-vote principle does not apply to the country because Thai elites believe that Thai people—especially rural voters who are perceived as poor, uneducated and ignorant—are not ready for democracy. PPRP MP Kasidej Chutiman echoed this view during the voting process for the PM: “People are born unequal, their appearances are not similar, education is unequal, human relationship is unequal. There is nothing in the world [that is] equal.” On the other hand, Thai progressives, especially the young generation, have called for equal political rights under an electoral democracy, and for freedom of expression so that they may freely express their grievances, political views and interests. These conflicting ideologies have unprecedentedly deepened political cleavages in Thailand.

After five years, the Thai junta finds difficulty to remain in power without legitimacy. The junta had no choice but to whitewash itself through the recent election in order to maintain control over the government. PPRP’s success in cobbling together a government illustrated that the junta has seen the need to use democratic processes for its transition toward legitimacy. Sontirat Sontijirawong, PPRP Secretary-General, articulated this discourse when he called the anti-junta parties to “stop calling themselves the ‘democratic front’ and calling their opposite parties ‘pro-dictatorship.’” Pointing out that both camps had been elected by the people, he said “Democracy is about respecting peoples’ decisions…[so] Palang Pracharath is also a pro-democracy party.”

When an authoritarian tries to democratize, a new term is often coined to describe the transition. Such a term emerged during the prime minister selection vote on 5 June, when unelected Senator Seri Suwanphanon said, “I was accused of being in favour of a dictatorship. I am in favour of a democratic dictatorship, but not fake democracy.” He was expressing his belief that Thais have lived in freedom during the junta’s authoritarian rule. While his belief is definitely fallacious, the controversial term—an oxymoron combining opposing concepts of democracy and dictatorship—has since gained broad use among the public to describe the post-NCPO political order.

Shrinking Political Spaces

Arguably, the Thai junta cannot be seen as a democratic regime, no matter how hard it pretends to be one. Thai society has paid a high cost for the authoritarian regime in terms of the loss of civil liberties and political rights. According to iLaw in its five year statistics of NCPO restrictions as of May 2019, 1,318 persons were summoned to report or visited at his/her place; 625 individuals were arrested; 99 were charged with lèse majesté law; 117 were charged with sedition law; 421 were charged for “illegal” political assemblies of more than 5 persons; and, 1,886 were tried at military courts.

The Thai junta’s legacy of restricting freedom of assembly through NCPO order no. 3/2015, prohibiting political assemblies of more than five people, lives on through the 2015 Public Assembly Act, which intends to make a political mobilisation as small and complicated as possible. For example, those planning to stage a public assembly are required by the law to inform the head of a police station at the target area at least 24 hours prior, with the officer given the authority to grant permission based on his/her discretion. Without such permission, the assembly will be illegal. The Public Assembly Act carries forward the junta’s viewpoint that those activities are public disturbances instead of exercises of basic human rights.

The 2019 Freedom in the World report of Freedom House rated Thailand as “not free” as its freedom of expression, political rights and civil liberties have been restricted by unchecked powers of the military government. The junta employed censorship, intimidation and legal actions to limit freedom of expression and freedom of assembly over media, civil society organisations and academics. A surveillance society, both online and offline, has been created to monitor political activities and views that criticize the junta.

With General Prayut’s continuation as Prime Minister, the significance of democracy has been diminished in favour of values favoured by so-called Thai-style democracy. However, the current political imperative demands that democracy’s substantive values—such as political rights, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly and civil liberties—must be ensured for people in the country.