By Clarissa V. Militante

The dusts from the melee of fleeing Red Shirts and assaulting teams of soldiers have settled, and not even the hint of smoke from the burned buildings could be detected. Bangkok’s residents are now trying to pick up on the routines of their daily lives before the red-shirted protesters mounted mass actions in large sections of central Bangkok from March to May. But for the Thai intellectuals, this seeming lull is a chance to take a more in-depth look at the recent past events and deal with nagging issues that confront Thai society.

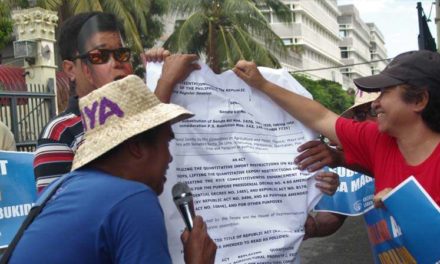

Is it a class struggle—being manifested in a brewing civil war—that is unraveling in Thailand? This was a major question raised during the Philippine forum “Thailand: Democracy, People, Power” organized by the Focus on Global South Philippines, a week after the military dispersed the Red Shirts and dismantled their camps that have become part of Bangkok’s landscape in the past two months. Joy Chavez, Philippine Programme Coordinator of Focus, moderated the discussion.

In the May 28 forum held at the University of the Philippines-Diliman, Ubonrat Siriyuvasak said that the Thai government did not consider the Red Shirts a democracy movement, but merely a group loyal to former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra and whose main goal is still to bring back to power the former head of state who was convicted of corruption charges after a military coup in 2006 ousted him. This is the same perspective predominant in local and international media reports, Siriyuvasak added. Siriyuvasak, one of the three main guest speakers in the forum, is Deputy Dean at the Faculty of Communication Arts in Chulalongkorn University and an advocate of media reform.

The Red Shirts first hogged news headlines in 2008, two years after Thaksin was removed from office; they were perceived as having been organized and funded by the former leader. Formally called the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD), the Red Shirts are mostly from the rural poor of the north and northeast regions of Thailand, but are also supported by youth and student activist groups. Their votes supposedly helped Thaksin win landslide victories in two elections, as they were the main beneficiaries of his populist policies and programs. However, it has also been the Red Shirts’ assertion that they are fighting for democracy and against the country’s elite, whom they accused of being behind the coup that illegally put the military in power. The UDD refuses to recognize the current government headed by the British-educated Abhisit Vejjajiva.

Siriyuvasak did not entirely agree with government’s point of view and argued that the Red Shirts should not be readily dismissed as Thaksin’s pawns. The movement, she said, is an “alliance of peasant groups, lower middle class, and lower classes” and that the Red Shirts see themselves involved in a class struggle. “They call themselves ‘Prai’ or common, ordinary citizens fighting for political rights which they believed were taken away from them,” explained Siriyuvasak.

Siriyuvasak also hinted on ethnic divide as another angle that may be looked into in understanding the red-shirted movement, but qualified that this is “not as pronounced as the class orientation.” She cited media reports on the involvement of North easterners “who do not speak Thai as their first language,” indicating that this language issue “reflects some form of alienation of these ethnic groups and not just as regional groups.”

For Siriyuvasak what is happening in Thailand is the “unfinished project of nation-building.”

Philippine lawmaker, House Representative Walden Bello, shared this viewpoint that current developments in Thailand are unresolved issues in the country’s political history. He traced back the roots of the current “state of civil war in Thailand” to the “withdrawal of the military from power, which ushered in a new era in Thailand.” This new political era that began in the 1980s coincided with an economic boom in the country, which highlighted “stark disparity between Bangkok and rural Thailand.” However, the political parties that were put in power failed to address poverty, Bello underscored, even as he also characterized the struggle as “based on conflict between the elite and the middle class, against the rural and urban poor.” Bello also said that the 2009 UDD mobilizations were precursors of what happened recently.

“Thaksin rose and benefited from globalization; and he rounded support from those discontented with [it]. He put in place some policies that focused on those who were eased out and marginalized by previous government policies, such as the 1 million Baht program in the countryside. These programs created a solid base, which became the base of the Red shirts,” explained the Philippine lawmaker and author of “A Siamese Tragedy: Development and Disintegration in Modern Thailand,” published in 1989.

The coup in 2006 greatly polarized Thai society, witnessing the organization of the yellow shirts as counterpoint to the red-shirted UDD members, Bello said. The yellow shirts are mostly from the middle class, who wanted Thaksin out because of corruption in his government.

What was a glaringly recent development however, Bello pointed out, was the openly critical attitude towards the King exhibited by ordinary citizens. When he was in Bangkok in the week the military launched its attack on the protesters, Bello had the opportunity to talk with taxi drivers who thought the King represented elite interests.

Thai human rights defender Sarawut Pratoomraj criticized the military’s issuance of the Emergency Decree in April. “Emergency Decree is not Martial Law; it looks softer but it is in fact harsher than Martial Law…because it clamped down on the people’s movement; the people’s right to freedom of expression,” argued Pratoomraj, who works with the Human Rights Organization of Thailand.

Pratoomraj shared some video footage that showed witnesses’ account of how people were shot dead and how military personnel got rid of bodies. He himself recounted how demonstrators were shot dead in the head by unidentified gun men, which the government said were not from the military. “This is the first time that such a harsh operation took place, with demonstrators getting shot so brutally,” Pratoomraj said, quoting reports that put civilian death toll at 80 from the time the Red Shirts clashed with the military in April 10 until the protests ended in May.

The human rights defender attributed the failure in the negotiations between the Abhisit government and the UDD to the emergency decree, which “in effect resulted in the monopoly of power of government, controlling now all ministries, the police and military.”

“At one point, Abhisit announced the five-step Roadmap, which set elections for November. But while negotiations were taking place and a press conference was held announcing the eventual surrender of some UDD leaders, the military continued to surround and enclose the area,” Pratoomraj said.

Photo by Joseph Purugganan