by Joseph Purugganan*

This article was originally published in the website and sponsored by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung (RLS) with funds of the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development of the Federal Republic of Germany. The content of the publication is the sole responsibility of the author and does not necessarily reflect the position of RLS.

In March 2024, the European Union and the Philippines announced the resumption of negotiations on a “comprehensive and modern” free trade agreement (FTA). After two rounds, the two parties have commenced discussions on a wide range of areas and substantially concluded negotiations on the chapters concerning Transparency and Micro, Small, and Medium-Sized Enterprises (MSMEs) and Sustainable Food Systems (SFS).

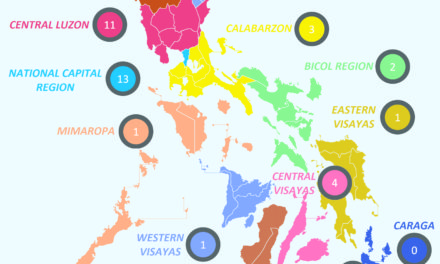

The momentum and energy from the first two rounds of renewed talks are a far cry from the earlier attempts to jumpstart negotiations almost a decade ago, which stalled after just a few rounds held over a four year period. The bilateral EU-Philippines negotiations were launched in 2015 as part of what the EU then referred to as New Partnerships with Asia — a push for trade agreements with key Asian states, namely India, Korea, and initially the regional ASEAN bloc. The region-to-region approach for ASEAN was suspended in 2009 with the EU shifting to bilateral negotiations first with Singapore, then Malaysia in 2010, Vietnam in 2012, Thailand in 2013, the Philippines in 2015, and Indonesia in 2016.

A host of reasons have been given for the suspension of talks with the Philippines in 2017 while President Rodrigo Duterte was in power, including “Duterte’s shifting foreign and domestic policy strategies, his hostility towards the West, as well as EU concerns over human rights issues in the Philippines, its commitments to GSP+, and issues related to intellectual property rights in the FTA negotiations.”

Buoyed by the change in administration from Duterte to Ferdinand Marcos, Jr, and the ensuing normalization of economic ties between the two parties, the goal for the second attempt is to secure an agreement within two years through an expedited process that will include “inter-sessional virtual meetings between rounds to continue discussions and progress on internal consultations as needed”.

Uncertainty and Spiralling Trade Wars

The talks are now proceeding through very difficult and challenging times. US President Donald Trump’s tariff policies have caused major disruptions in the global economy and ignited a global trade war, with China fighting back with retaliatory 125 percent tariffs on goods imported from the US and working with other countries to unite against what President Xi Jinping has referred to as “bullying” from Washington.

If there is a silver lining to Trump’s reciprocal tariffs and the ensuing trade wars, it is the realization that free trade agreements are now “not worth the paper [they are] written on”, as one Canadian economist put it. The US, for example, has current FTAs with most of the 57 countries it levied additional tariffs against.

In the past, FTAs were touted as one of the pillars of the rules-based trading system, grounded in the principles of trade without discrimination, predictability, transparency, and fair competition. However, these unilateral actions reveal a highly skewed system in which powerful economies like the US can essentially flex their muscles and weaponize trade instruments like tariffs to suit their own economic and political agendas.

Why the Philippines Wants the FTA

For the Philippines, the rationale for engaging with the EU falls under the strategic objectives of 1) securing permanent access to additional duty-free markets beyond those covered under the GSP+ system, 2) establishing a framework that is conducive to attracting greater investments from the EU, and 3) being on par with other ASEAN member states who are aggressively pursuing FTAs with the EU.

While on the surface there seems to be a congruence of interests between the EU and the Philippines, there clearly is a power imbalance in favour of the EU with respect to both critical minerals and digital trade.

One sector that is both top of mind for the Philippines and critical in today’s technology-driven global economy is electronics and semiconductors. This sector makes up close to 60 percent of Philippine commodity exports. The Philippines is not only seeking to increase its exports to the EU, but also hoping to entice more EU investments in its domestic microchip industry. Currently, the top two EU destinations are Germany, at about 4.9 percent, and the Netherlands, at about 2.5 percent. In light of Trump’s tariffs, there is also an added sense of urgency to diversify and expand export markets. As a selling point for the EU-Philippines FTA, the Philippine government is touting an untapped and previously unrealized EU export potential amounting to 8.3 billion dollars (7.3 billion eurp).

The EU’s Strategic Agenda

In line with the changed geopolitical context, the EU has recalibrated its global trade agenda to increase its focus on the Indo-Pacific region. This focus is motivated by a desire for access to the region’s growing market and raw materials, with the goal of containing China’s growing power and influence.

A major motivating factor amidst shifting geopolitical dynamics continues to be the question of how to counteract China. A big part of the global economic strategies of both the US and the EU is challenging China’s dominance (i.e., its massive Belt and Road initiative, its inroads into Asia and the Pacific through agreements like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), and its control over critical raw materials).

Artificial intelligence (AI), for example, is at the centre of efforts to advance the digital transformation of the global economy. It has become such a critical component of how big economies like the US, the EU, and China frame the future of the global economy that it has inevitably been cast as a security issue. And in this sector as well, we see the crucial interplay of trade, technology, and security.

Both the US and the EU have well defined policies to regulate the use and trade of the semiconductor technologies and applications that are the key drivers of the AI revolution. These policies are designed to achieve two goals: bolster the competitive advantage of companies based in the EU and the US in developing and exporting these technologies, which includes addressing supply chain barriers; and prevent other countries from gaining access to these technologies. This notably pertains to China, which is making an effort to develop its own AI capabilities.

New Elements of the Agreement

Two new main elements stand out in the current negotiations with the EU: 1) critical minerals, energy, and raw materials and 2) digital trade.

The FTA is seen as an important tool for ensuring the resilience and sustainability of supply chains, but also for encouraging direct foreign investments in mining and processing these minerals, of which the Philippines is a key source: “The Philippines has the world’s fourth-largest copper reserves, fifth-biggest nickel deposits and is also rich in cobalt”, and it has considerable deposits of gold and silver as well. The Philippine government estimates that only about “5 percent of these reserves have been explored, and only 3 percent are covered by mining contracts”. Amid increasing global demand, these largely untapped reserves are therefore fuelling the drive to expand mining projects.

With respect to digital trade, the EU’s negotiating position will be determined by its digital agenda, the overarching goals of which are to ensure predictability and legal certainty for businesses, to ensure a secure online environment for consumers, and to remove unjustified barriers.

The proposed digital trade chapter contains almost 20 binding provisions on a wide range of issues, including a ban on customs duties on electronic transmissions and prohibitions on what are referred to as unjustified government access to software source code, unjustified barriers to data flows, including data localisation requirements, and protecting privacy.

For the Philippines, on the other hand, digitalization poses both opportunities and challenges. The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) reported that, in 2023, “the digital economy amounted to PhP 2.05 trillion, contributing 8.4 percent to the country’s Gross Domestic Product” and represents one of the fastest growing markets for digital trade. The government is banking on the potential expansion of the digital market and trying to position the country as a “digital trade hub”.

However, the challenges include an inadequate digital infrastructure and the gaping digital divide not just in terms of access but also the skills necessary to actively participate in and benefit from the transformation of the economy. A trade policy dialogue organized by the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) in April 2024 highlighted the fact that the digital trade negotiations are focused on establishing rules and disciplines, an area where it has to do a bit of catching up in the face of frenetic technological development.

On the issue of trade and human rights, the European Union seems to favour sweeping aside continuing concerns over human rights under the Marcos administration, the key concern that sidetracked the negotiations in 2017.

Another major challenge for the Philippines lies in ensuring that broader public interest concerns over security and data privacy, access to and control over data, and benefit sharing are adequately taken into consideration amid the move towards integration into the digital economy.

While on the surface there seems to be a congruence of interests between the EU and the Philippines, there clearly is a power imbalance in favour of the EU with respect to both critical minerals and digital trade. This unequal relationship stems not just from the obvious difference in the level of development, but also from where the two parties and the corporations that they host are placed within the global value chains. The imbalance is further institutionalized through the rules that are being put in place via the FTAs — rules that are designed to favour and advance the interests of big corporations.

With respect to critical minerals, while the Philippines is an important source of raw materials, there are other sources within the region (most notably Indonesian nickel reserves) competing for the same low-end position in the value chain. The EU, on the other hand, holds considerable power to leverage the interests of its companies in more value-adding positions along the chain, from smelting, refining, and processing to manufacturing products like EV batteries. Countries like the Philippines face severe restrictions on their ability to enact policy measures like export restrictions, for example, to support movement up the value chain. Furthermore, the trade rules are shifting more and more towards supporting supply-chain resilience and preventing disruptions to the flow.

On digital trade, EU tech companies dominate, securing as much as €74.4 billion in 2024 through various deals. Top companies include Sweden’s Northvolt and Automotive Cells Company in France, both of which produce lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles and energy storage systems. These companies are at the high end of the value chain. As one study on power and global value chains pointed out, “States whose businesses are higher on the global supply chain will have more opportunities to influence prices and product standards than states whose businesses are lower on the value chain”. The report further notes that this “suggests a ‘rich-get-richer’ effect, whereby the dominant powers sustain their economic advantages by reaping benefits from their high-value businesses in global supply chains”.

In Whose Interest and At What Cost?

Civil society groups and campaign networks like Trade Justice Pilipinas have consistently raised a number of key concerns and issues since the talks began in 2015.

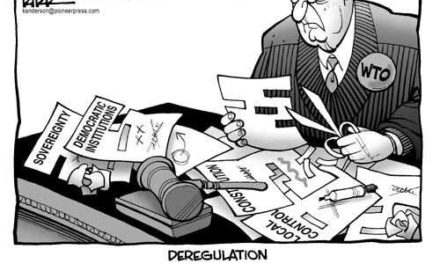

The issues include possible impacts on prices of medicines, access to affordable generic medications, and farmers’ rights to seeds in the intellectual property rights (IPR) chapter, as well as the erosion of policy space through provisions prohibiting measures like local-content stipulations, requirements pertaining to hiring local workers, export restrictions, and technology-transfer specifications.

FTAs curtail states’ power to regulate when rules developed and pushed by big corporations are rigged in their own favour. Powerful tech companies, for example, have pushed rules against data localization, local content, source code disclosure, and the introduction of taxes on companies. These corporate-driven rules would have huge implications for government revenues, privacy and consumer protection, security and law enforcement, and policies in support of domestic industrialization and development.

Revenue losses resulting from a ban on duties on electronic transmissions, for example, are estimated to have cost developing countries around “USD 48 billion in tariff revenue from duty-free imports of specific ET products from 2017 to 2020”.

Lastly, on the issue of trade and human rights, the European Union seems to favour sweeping aside continuing concerns over human rights under the Marcos administration, the key concern that sidetracked the negotiations in 2017.

The EU-commissioned Sustainability Impact Assessment, released in 2019, already raised concerns about possible impacts on human rights, particularly those of indigenous people, women, and children. The assessment pointed out that, “if not countered by appropriate measures, more people could be at risk of being exposed to poor working conditions” due to the rapid expansion of certain sectors. This particularly applies to industries where human rights issues persist, such as textiles and garments, where child labour is used, or the mining sector, which is often at odds with indigenous people’s rights.

The summary assessment report 2022 on GSP+ also highlighted “a number of concerning issues in the case of the Philippines, including the war on drugs, shrinking civil society space, attacks on human rights defenders, the possible reintroduction of the death penalty, and lowering the minimum age of criminal responsibility.

Conclusion

Overall, three main questions and concerns remain with respect to these ongoing negotiations.

First, do we need a trade deal in this moment of instability? How much value does an FTA with the European Union hold for the Philippines during these uncertain times? Will it provide the desired stability and predictability amidst a volatile situation, or will the obligations and commitments serve as binding constraints on the country’s own development goals?

Considering the nature of twenty-first century global trade, in which a great deal of the exchange goes through global value or supply chains and developing countries like the Philippines are often at the end of those chains or sources of raw materials, this deal will lock the Philippines into rules that favour big corporations.

Furthermore, the restrictions that will be imposed on the Philippines, whether on critical mineral or digital trade, would severely limit its policy space to support its own development agenda, especially in light of popular demands for more just and equitable development policies.

The continuing campaign to stop the EU-Philippines FTA needs to navigate these very challenging times and confront the strategic issues from the perspective of working-class people and marginalized sectors.

Amidst the uncertainly caused by unilateral US actions, developing countries like the Philippines need more flexibility to negotiate. Committing to digital trade rules, such as those that would be imposed under the FTA with the EU, would limit the ability of the Philippines to leverage concessions in negotiations with the US and other parties.

Second, while there has been a lot of emphasis on maximizing or realizing untapped potential, the Philippine experience with FTAs generally has not been good in terms of delivering promised benefits and gains. We argued in the RCEP campaign, for example, that based on experience, the rosy projections and promises of benefit for all under a liberalized trade regime have simply not materialized. Instead, we have seen how corporate-driven globalization has led to an agricultural sector in crisis and de-industrialization. The Senate recognized the need to enact measures that would enhance competitiveness in order to ensure that benefits from these agreements redound to the working classes.

However, it is clear that the FTA would further restrict the government’s policy space for prioritizing competitiveness-enhancing policies and programmes to ensure that potential benefits are actually realized and that they accrue to the needs of working class people.

Finally, it is clear that on the new issues (technology and digitalization, energy, and critical minerals), the European Union has a more developed and strategic agenda for securing its interests and those of large corporations. By committing to the rules that will be set under the agreement, the Philippines would be coerced into accepting revenue losses and restrictions on its ability to regulate trade and investments to ensure its own development goals without interrogating the issues of equal benefits, on the one hand, and shared obligations to address negative impacts on the environment and human rights, on the other.

The continuing campaign to stop the EU-Philippines FTA needs to navigate these very challenging times and confront the strategic issues from the perspective of working-class people and marginalized sectors. The tasks at hand are to document and expose the critical issues around the negotiations and the negative impacts on the Philippines, particularly the marginalized sectors — workers, women, farmers, fishers — highlighting the issue of human rights as a possible deal breaker. Civil society also needs to increase awareness of new issues such as digital trade, energy and critical minerals, trade, and security issues and expand the campaign constituency by linking with campaign groups, networks, and movements working on environmental issues, digital rights, human rights, and security.

—

Joseph Purugganan is the co-director of Focus on the Global South and a co-convenor of the Trade Justice Pilipinas campaign network.