By Benny Kuruvilla*

The Global Food Crisis, this time

A dossier by Focus on the Global South

A perfect storm is brewing in the global food system, pushing food prices to record high levels, and expanding hunger. The continuing fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine War, climate-related disasters and a breakdown of supply chains have led to widespread protests across the global South triggered by the spiraling food prices and shortages.

As international institutions struggle to respond, some governments have resorted to knee-jerk ‘food nationalism’ by placing export bans to preserve their own food supplies and stabilise prices. While this is an understandable defensive response, the solution lies in a more systemic, transformative approach.

In this dossier, researchers from Focus on the Global South write about various aspects of the current crisis, its causes, and how it is impacting countries in Asia. These include regional analysis, case studies from Sri Lanka, Philippines and India, the role of corporations in fuelling the crisis and the flawed responses of international institutions such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the Bretton Woods Institutions and United Nations agencies. We also attempt to present national, regional and global aspects of a progressive and systemic solution as articulated by communities, social movements and researchers at multiple levels.

Articles will be published every week till mid-October. Other articles included in the dossier can be found under this tag here.

2022 has been a tumultuous year for Sri Lanka; a full blown economic, food, debt, energy and humanitarian crisis, resulting in a spectacular popular movement in March 2022 that succeeded in overthrowing an authoritarian and inept regime in a matter of months. But after the initial euphoria of a new dawn, the island nation saw a bizarre, tragic return to status quo with a new Government led by a compromise candidate – veteran politician and former Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe who assumed power from July 2022.

Since then, President Wickremesinghe, who is close to the previous discredited Rajapaksa regime, has deflected attention from urgent systemic reforms and instead targeted protestors and used the controversial Prevention of Terrorism Act to detain protest leaders without charges. In an interview with the Economist Magazine in August 2022, Wickremesinghe laid out his economic roadmap to surmount the current crisis:

‘My idea is to do a deep cut and make a legislative framework for a highly competitive export-oriented economy…. we are looking now at disposing of some state assets, which will give us about $2bn-3bn. You can sell Sri Lanka insurance, there’s telecoms… In South Asia itself I can’t see very much regional integration, so we will look at closer relations with ASEAN [Association of South-East Asian Nations] and RCEP [Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, an Asian trade pact].

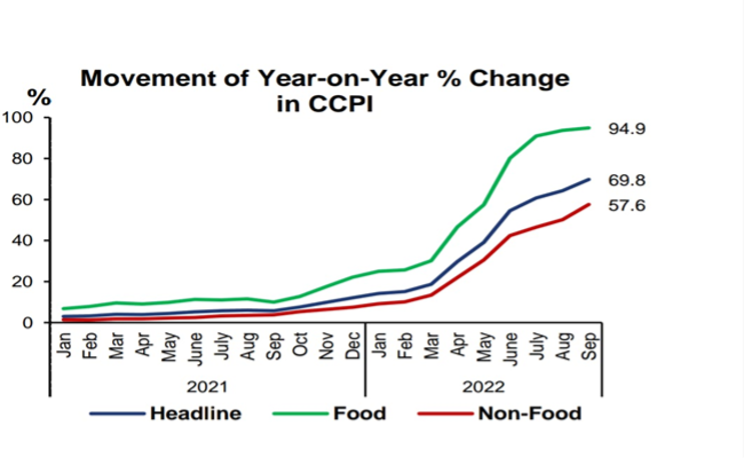

Predictably with this sort of approach, little has changed in the past six months since the protests began; Sri Lanka continues to be on a powder keg with rampant inflation that hit 70% in September 2022 (see figure below), a continuing livelihood crisis and an expected December 2022 bailout package from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) with neoliberal conditionalities such as cuts on public spending, privatisation and other austerity measures that will likely spark a further round of protests.

Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka. Colombo Consumer Price Index. Inflation statistics for September 2022.

Context to the 2022 crisis

Sri Lanka is no stranger to crises and protests, though the current one surpasses anything the country has seen since its independence from British rule in 1948. Longstanding tensions between the Tamil minority in the northeast region and the Sinhala majority led to a protracted civil war that began in 1983 between separatist militant Tamil groups and the Sri Lankan state. The civil war reached a bloody end in 2009 resulting in the ruling Rajapaksa clan further cementing their dominance over national politics. Widespread concern and international condemnation, including from the United Nations (UN), on tens of thousands of civilian deaths and human rights abuses in the Northern and Eastern provinces where the Tamil population is significant was ignored. From 2009 onwards, President Mahinda Rajapaksa ruled with an iron fist; his formula for economic growth was a toxic mix of trade and financial liberalisation, privatisation and promotion of large infrastructure projects financed by international loans. Rajapaksa only further entrenched the trend of neoliberal policies that the country’s leaders embraced over three decades earlier, albeit with his unique imprint of authoritarianism and crony capitalism that immensely benefited his extended family and close associates.

Sri Lanka has long been the poster boy of neoliberalism in the region; it was the first South Asian country to embrace open market policies way back in the late 1970s. This was after a short-lived dalliance in the 1950s and 1960s when regimes led by the socialist Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) implemented a set of heterodox economic policies including nationalisation of key sectors such as insurance, banking, petroleum and import substitution industrialisation (ISI). Subsequent governments starting from the J.R. Jayewardene-led United National Party (UNP) regime, at the advice of the Bretton Woods Institutions, reversed much of these and undertook open market reforms, reduced government spending and furthered trade and financial liberalisation by revoking the earlier ISI policies. The researcher Balasingham Skanthakumar from the Social Scientists’ Association (SSA) and Committee for the Abolition of Illegitimate Debt (CADTM) documents that:

‘Neo-liberal policy reforms contributed to loss of employment in certain sectors through the cheaper price of certain imported products as compared to their locally manufactured equivalents. For example, the liberalisation of textile imports post-1977, caused the collapse of the domestic handloom sector, in which women predominated, comprising cottage industries and state-owned mills. By 1986 it is estimated that over 120,000 jobs had been lost as a result. Likewise, there was large-scale retrenchment of public sector workers (estimated to be around 100,000) in compliance with structural adjustment conditionalities in 1990; and many of these were women who constituted almost 40 percent of state employees’

A debt crisis years in the making

While much has been written about the causes of the present crisis, the dominant narrative within Sri Lankan policy and government circles is that a combination of the 2019 Easter Sunday bombings in which more than 260 people died (leading to a crash in tourism revenues) and external shocks such as the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2022 Ukraine War were the main triggers that resulted in a collapse of the economy and the debt crisis. The truth is less dramatic; a more sober historical perspective shows that these factors only served to hasten an imminent crisis in a country where successive governments failed to diversify the economy, invest in domestic agriculture and instead embraced a highly vulnerable export-import dependent development model financed by international aid and finance. Sri Lanka has the dubious distinction of having gone to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for assistance 16 times since 1965. In addition during this period, Sri Lanka also borrowed some US$3.49 billion from the World Bank and US$8.64 billion from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) for projects ranging from infrastructure, human development and financial innovation.

All of this financial assistance from the Bretton Woods Institutions and the ADB, egged on by domestic votaries of the free market, deepened privatisation, trade and financial liberalisation, reduced government welfare, opened up sectors for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and the rupee was put on free float. In addition, from 2009 onwards, armed with a new constitutional amendment that gave him sweeping powers for a new generation of neoliberal economic reforms, President Rajapaksa embarked on an infrastructure building spree (roads, airports, ports, special economic zones, and hotels) with additional finance from bilateral donors such as China, Japan, India and private investors. Financialisation resulted in money being pumped into real estate development, the stock market and tourism in the expectation of future windfall profits.

Nothing of the sort happened. The much-vaunted FDI averaged only around US$1 billion a year from 2000-2020. Contrast this with migrant remittances, mainly from women domestic workers in the Gulf countries, which exceeded US$7 billion a year in the decade prior to the pandemic. Migrant remittances were more instrumental at propping up the economy than foreign investment but at the peak of the pandemic in 2021, they dropped to their lowest in a decade at US$ 5.49 billion (the corresponding FDI figures in 2021 was at US$ 600 million) as the trade deficit widened and imports spiked.

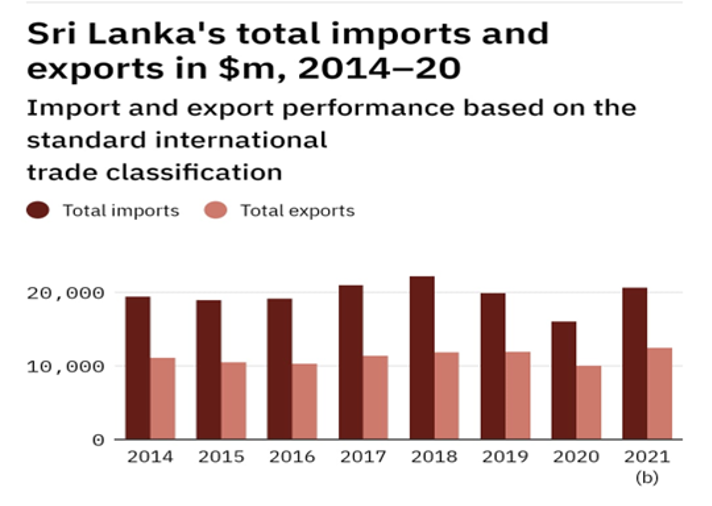

Another legacy of neoliberalism is the lack of industrialisation. Sri Lanka was stuck in low value-added ready-made garments with much of the raw materials such as thread, dyes and cloth being imported. It imports virtually everything else from expensive intermediate equipment to finished manufactured goods such as factory machinery, automobiles, household appliances, heavy vehicles and construction equipment. As the table below from the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) shows, imports have consistently been double the export bill.

Source: Central Bank of Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka’s total imports and exports from 2014-2021.

In such a scenario of declining exports coupled with the rupee in a free fall, the total stock of debt kept mounting as the country kept borrowing just to service its existing debt. Many of Rajapaksa’s marquee projects such as the Hambantota port, Colombo port city and the Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport that together cost US$19 billion turned into proverbial white elephants in a stagnant economy. In 2022, Sri Lanka had to pay US$ 7 billion just to service its external debt, but as it ran out of foreign exchange services it has declared that it will default on external debt payments amounting to some US$ 51 billion.

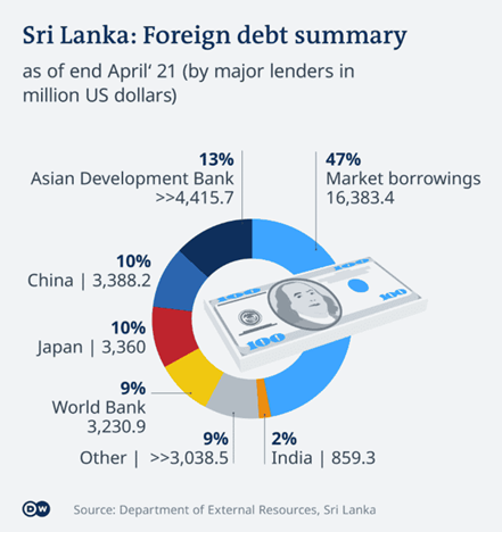

As Sri Lanka’s national debt reached an all-time high of US$ 86.8 billion in December 2021, many mainstream media outlets blamed China for leading it into ‘debt trap diplomacy’. This view gained credence because of the widespread belief that in 2017, when Sri Lanka was unable to pay back part of its debt, China supposedly seized control of the Hambantota port. Commentators from Sri Lanka have clarified that there was no such default. Rather, as the port was underperforming, based on advice from SNC Lavalin – a Canadian engineering firm, the Sri Lankan Government leased out operations to a Chinese firm called China Merchants Port (CM Port) Holdings. The 99-year lease was worth US$1.12 billion and was used to bolster Sri Lanka’s dwindling foreign reserves, not pay off China’s debt. The lease did not result in any change in ownership; The Sri Lankan Government owns the port while commercial operations of the port are handled jointly by CM Port (70% stake) and Sri Lanka Ports Authority (30%).

While it is a fact that China is involved in many infrastructure projects such as Hambantota in terms of both implementation and providing finance, data from the Department of External Resources showed that out of the total foreign debt ( see figure below ) owed by Sri Lanka, China’s share stands at around 10%. Rather, nearly 80% of the country’s foreign debt was owned by institutions in/and controlled by the US, EU and Japan. Under the heading of market borrowings, which are mostly international sovereign bonds (ISBs), the main holders of Sri Lanka’s debt are BlackRock (US), HSBC (UK), JPMorgan Chase (US) and Prudential (US).

Agrarian crisis and food insecurity

The crisis of Sri Lankan agriculture is also intertwined with its colonial British legacy and its tryst with neoliberalism from the 1970s. The British introduced plantation crops such as rubber, tea and coffee which then became the mainstay of the country’s export basket for several decades after its independence. The focus on plantations and the subsequent shift to an open economy model crippled peasant agriculture from which it has never recovered.

The late Sarath Fernando of the Movement for Land and Agrarian Reform (MONLAR), in a 2007 article, asserted that under the guidance of the World Bank, land reforms were stalled in the 1970s and government support services and protections given to small-scale farming and domestic food production were withdrawn. This led to a near complete breakdown in the livelihoods of peasant farmers. On the other hand, despite contributing to a prominent and vibrant sector of the economy, plantation workers, who are mostly of Tamil origin, were underpaid and remain amongst the most impoverished sections of the working class.

Sri Lanka then gets locked in a vice grip where there is little economic diversification and much of its working population continues to be dependent on a crisis-ridden agriculture sector. In 2020 while it contributed only 7% to GDP, more than 23% of the population was employed in agriculture and related activities. With chronic under-investment in domestic agriculture and withdrawal of state support for credit and extension services, the country turned to imports of basic food such as wheat flour, rice, sugar, fruits, fish, milk and milk products. It is estimated that imported calories contribute some 22% of the caloric consumption of an average Sri Lankan household. Further, data shows that food poor and urban families eat more imported calories as they are more cost-efficient.

In 2020, with the onset of the pandemic, Sri Lanka’s debt crisis deepened as its key export sectors were hit. With lockdowns imposed across the world, tourism took a body blow and remittances reduced as many Sri Lankans lost jobs abroad. Faced with a foreign exchange crisis and mounting debt payments, the Government scrambled for a way to reduce its import bill. In a now much critiqued knee-jerk reaction, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa announced in April 2021 that all agrochemical imports were banned from May and Sri Lankan agriculture would turn organic. Despite warnings from agricultural scientists and farmers groups that this would be an unmitigated disaster, the Government went ahead, relieved that it had saved up to US$400 million in foreign exchange. As predicted by experts, paddy productivity dropped 45%, maize output plummeted from 415,00 MT in 2020-2021 to just 60 MT in 2021-2022. Tea production also dropped by 20% in the corresponding period. Prices skyrocketed and the Government withdrew the policy within six months but much damage was already done.

The way forward

Governments of various shades embraced neoliberalism at the advice of the Bretton Woods Institutions and the ADB in the name of rapid economic growth, reducing inequality and indebtedness. Over four decades of neoliberalism in Sri Lanka have seen growth plummet, inflation skyrocket, a sovereign debt default, job losses, rising hunger and inequality. Ironically, as the working classes in Sri Lanka struggle to survive amidst these multiple crises, these same institutions are back in the game and, together with the country’s discredited political elite, are calling for more of the same policies that got them in this mess in the first place.

Social movements leading the protests recognise that the current conjuncture in Sri Lanka is not about a singular debt crisis, or a food and energy crisis or just a crisis of the regime. It is multiple interlinked political, economic, social and environmental crises of an entire paradigm of neoliberal development. The whole structure of a militarised, authoritarian undemocratic state needs to be dismantled.

In terms of addressing the food and agrarian crisis, progressive economists have argued that the earlier attempt at land reform should be urgently revived. The parliament could consider an emergency programme to distribute land, especially to marginalised sections of society so they can sustain themselves. Promotion of cooperatives, aligning them with rural producers’ needs and other social institutions with adequate financial and technical support from the state can help address the current food crisis and lead to food self-sufficiency.

As we write this, the World Bank and the IMF are concluding their annual meetings (10-16 October 2022) in Washington, D.C. The meeting is being held in a fraught global environment in which economists are predicting a coming storm of debt distress in other countries in the developing world similar to what is happening in Sri Lanka. Global civil society including Focus on the Global South have issued an urgent call to the meeting. Our demands include: immediate debt cancellation by all lenders for countries to enable people to deal with the multiple crises; and reparations for the damages caused to countries due to the contracting, use and payment of unsustainable and illegitimate debt and conditions imposed to guarantee their collection.

After four decades of crisis ridden politics, Sri Lanka deserves better. The inspirational Janatha Aragalaya (Peoples struggle) movement has the potential to unite all progressive forces in the society on an agenda that meets the demands for social justice, economic alternatives and democratisation of the state.

While the youth were the most visible section of the movement, the Aragalaya comprises a wide range of groups cutting across ethnic, class and religious divides. This includes farmers unions, women’s groups, student associations, labour unions, civil society activists, professionals, artists, musicians, sportspersons, teachers, doctors, nurses and religious groups. This sort of alliance is unprecedented in Sri Lanka and, with the active participation of Tamil groups, is in some ways helping heal the wounds of the civil war. The times ahead are bound to be tumultuous and uncertain but the Aragalaya has ignited hope for a better future.

*Benny Kuruvilla is Head of India Office at Focus on the Global South