According to some economic managers of the Marcos administration, the root of the problem is the lack of food supply. However, the groups representing small-scale food providers said that the crisis should be attributed to the decades-long implementation of policies that are biased towards corporate profits and global markets. These have resulted in the decimation of the country’s food self-sufficiency and the extreme impoverishment of small-scale food providers.

“The long drawn and deliberate efforts to undermine the agriculture sector in favor of the policy of importation and agri-business also undermined employment in the agricultural sector,” said Wilson Fortaleza of Partido Manggagawa. This resulted in the “combined food and employment crises, while the sector that lorded and reigned over importation and local agribusiness have amassed super profits at the expense of the poor who have to confront hunger and higher food inflation on a daily basis,” Fortaleza added.

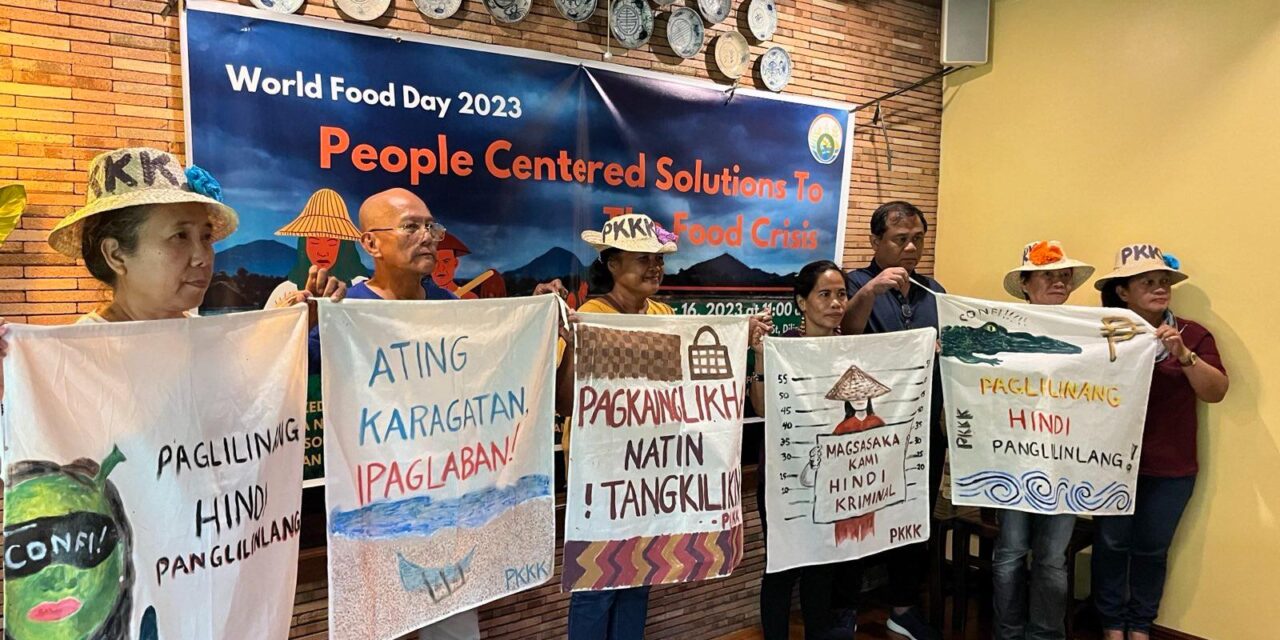

The group called for real and people-centered solutions to the crisis. First among these is the provision of government support to local small-scale food providers, while also halting intensive liberalization to protect the livelihood of small-scale food providers against unfair competition.

Janel Geconcillo of Pambansang Koalisyon ng Kababaihan sa Kanayunan said that the government’s continued pursuit of trade liberalization with the ratification of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) “endangers the livelihoods of local farming communities who cannot compete against cheaper imports. This leads to more indebtedness and displacement of farmers from their tillages, as opportunistic traders and middlemen seek to capture farmlands and place them in real estate markets.”

The statement issued by the group also stressed the need to give indigenous peoples and women special attention in the provision of production support, as they continue to face discrimination in their roles as farmers and fishers.

“Indigenous communities are often left out of these programs. In our experience, these relief programs are also being politicized and corrupted. Only those that have connections are able to secure access,” decried Indigenous woman leader Mary Ann Forton of Lilak. For this reason, the group expressed skepticism over the government’s food stamp program, which involves the identification of eligible beneficiaries for monthly meal assistance.

Geconcillo added that support services must be founded on the actual needs of small-scale food producing communities. In relation, Leticio Datuwata from Timuay Justice and Governance highlighted the dangers of support services such as mechanization that are detached from realities of small-scale food providers.

“Most mechanization programs lean towards making more profits for large agribusinesses, and have eroded indigenous traditions in agriculture,” Datuwata said. He added that while mechanization has been designed to streamline and enhance food production, it has also become “the bane of seasonal farmworkers, including indigenous peoples, and has also worsened rural unemployment.”

Another central solution to the food crisis, according to the group, is the protection of the rights of farmers, fishers, indigenous peoples, and women to resources for production. They gave various accounts of land and resource grabbing that are undermining their capacity to produce sufficient food for their communities and the country.

Emblematic of this is the reclamation, seabed quarrying, and commercial overfishing in Manila Bay and other fishing grounds. Pablo Rosales of Pangisda Pilipinas said that these result in the conversion of the nation’s sources of food into business ventures for corporate profits, while also denying the legitimate rights of artisanal fishers to earn a living in food production. “Our fisheries are rich in resources. Instead of allowing their continued destruction for corporate profits, we must ensure that these are used sustainably and with public welfare in mind,” asserted Rosales.

The collective statement issued by the group argued that conflicts arising from policies and investments that favor corporate control over natural resources “often end up with communities losing access to their land and resources, massive displacement, and destruction of livelihoods.”

Reemar Alonsagay of the Alyansa ng Kabataang Mindanao para sa Kapayapaan (AKMK) said that “the vicious cycle of violence and conflict in many Mindanao communities was always rooted in resource-based conflicts.” He lamented how the cycle of conflicts and poverty have discouraged young people from farming and fishing, thereby threatening the future of food-producing sectors. For Alonsagay, struggles for peaceful communities in Mindanao thus intersect with the struggles for the right to define their own food systems.

As such, the group argues that protecting human rights is inseparable from addressing the food crisis. “If the rights of small-scale food providers are not respected, the country can never realize food self-sufficiency. For this reason, the government must put an end to the systematic repression of farmers, fishers, workers, indigenous peoples, and women and youth food providers who stand up for their rights,” the group says.

“Systemic changes are needed, not palliative solutions,” the group further added, as these are critical in addressing hunger and the food crisis. According to them, if local small-scale food providers are prioritized by the government through appropriate policies and programs, they would have the capacity to feed the entire nation amid the food crisis and well beyond it.”

The full statement can be found here.

![[IN PHOTOS] In Defense of Human Rights and Dignity Movement (iDEFEND) Mobilization on the fourth State of the Nation Address (SONA) of Ferdinand Marcos, Jr.](https://focusweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/1-150x150.jpg)