As the agency that led the creation of the law’s implementing rules and regulations (IRR), NEDA is being held to account for the disastrous impacts of the law on poor consumers, farmers, and farmworkers.

Referred to as the Rice Liberalization Law (RLL) by opposition groups, RA 11203 has replaced the quantitative restrictions on rice imports with a 35% tariff for ASEAN imports and a 50% tariff for non-ASEAN imports. With these rates, imported rice especially from Thailand and Vietnam sell at very low prices against which local farmers cannot compete.

The RLL has also removed the regulatory functions of the National Food Authority (NFA) over rice importation and streamlined the process of acquiring import permits. Consequently, big businesses with massive capital have managed to dominate the industry and ship in massive amounts of cheap imported rice. Since January 2019, over 3 million metric tons (MT) of rice have been imported by the Philippines, thereby making it the world’s largest rice importer of the year.

Similar sentiments, bitter experiences

The Wednesday protest is part of a wider campaign that seeks to highlight the impacts of the RLL on the poorest sectors of society, raise their demands concerning the law and proposals for pro-farmer policies, and demand accountability from the government. The sentiments against the RLL that have been widely covered in recent weeks, however, are not new. Since the 1990s, groups strongly advocating for sustainable agricultural production have strongly opposed liberalization.

“We have never fallen short of resisting liberalization since the negotiations on the World Trade Organization Agreement on Agriculture,” recalled Val Vibal of Aniban ng Manggagawa sa Agrikultura (AMA). These pro-farmer groups have constantly argued that pursuing liberalization without adequate state support for local agriculture would only further weaken the already feeble sector.

This contention was reiterated with greater fervor last year after proposals of what was then the Rice Tariffication Bill were forwarded by both houses of Congress. Farmers then argued that the bill, if passed into law, would flood markets with cheap imported rice, discourage farmers from engaging in agriculture due to poor incomes, facilitate land conversion and land grabbing, and reduce local rice production.

With the implementation of the RLL, what were then sentiments and fears are now complemented by actual experiences on the ground. Contrary to the promises of RLL’s main sponsor Cynthia Villar and other proponents, the law has resulted in lower selling prices of palay for farmers and higher market prices for poor consumers.

Protesters tear an enlarged copy of RA 11203 to symbolize their rejection of the RLL. 2019 November 20. Pasig City, Philippines.

Disastrous for agricultural livelihoods

With the liberalization of the rice industry, traders have been reluctant to purchase palay from local farmers since imported rice is significantly cheaper. Thus, with less incentive to buy local palay yet the same power to dictate its selling price owing to their dominant position in the rice trading industry, traders now have a stronger bargaining position over local farmers.

Data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) show that farmgate prices of palay dropped by 33 percent—from P23 pesos per kilogram in September 2018 to a mere P15.50 in October 2019. However, farmers’ narratives reveal that the actual situation is much worse.

“Prior to the implementation of RTL, farmers were able to sell palay for at least P17 per kilogram,” pointed out Jaime Tadeo, leader of peasant group Paragos Pilipinas. “Now, the farm gate price of palay has dropped to P7 to P10 per kilogram.”

With this price point, Romeo Royandoyan of the policy research and advocacy group Centro Saka claimed that “farmers are obviously losing,” given that the average cost of producing a kilogram of palay is equivalent to P12.40.

Groups opposing the RLL “estimate that total losses of farmers for 2019 alone could reach Php 140 billion, or Php 30,000 per hectare. This is more than 10 times the damage wrought by Typhoon Yolanda to the agriculture sector in 2013, and it is all man-made.”

Aside from liberalizing and deregulating the rice industry, the RTL is also pushing for mechanization which will result in the massive displacement of rural workers. As such, the enactment of this law has led to further impoverishment not only of farmers but also rural workers as well as higher incidence of malnutrition.

Ruth Abalos of Aniban ng mga Magsasaka, Mangingisda at Manggagawa sa Agrikultura (AMMMA-K) decried the ironic state of affairs brought about by the RLL: “Despite the flooding of imported rice in the country, rice farmers and farmworkers themselves do not have rice to eat.”

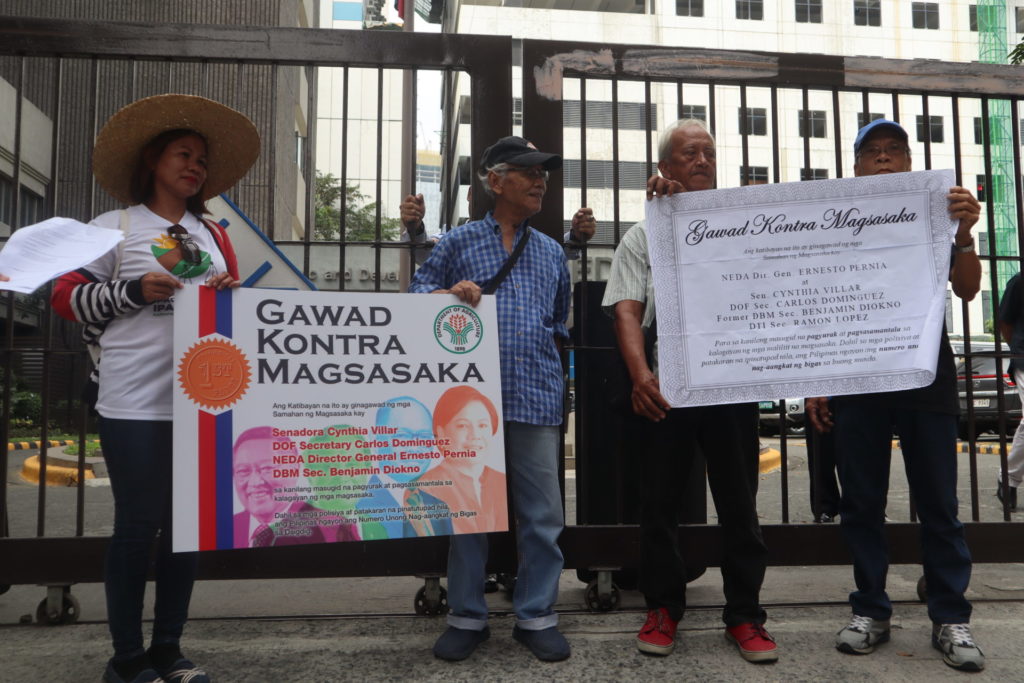

Farmers satirically grant the “Gawad Kontra Magasaka” (Anti-Farmer Award) to Senador Cynthia Villar, Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez, Economic Planning Secretary Ernesto Pernia, and Trade Secretary Ramon Lopez who have been the main proponents of the RLL. 2019 November 20. Pasig City, Philippines

Poor consumers share the burden

Consumers from urban poor communities who used to rely on the 27-peso NFA rice are also one of the most hardly hit sectors.

“Because of the RLL, NFA rice is no longer affordable for the poor as its price has gone up to P40 per kilogram,” said Erning Ofracio, chairperson of AKTIB which is a people’s organization for the urban poor.

With rice traders reportedly holding off their supply, consumer prices in local markets have indeed remained persistently high. According to PSA, regular milled rice retails at an average of P36.82 per kilogram, while well milled rice is priced at P41.73 pesos per kilogram as of the first week of November. This is still very far from the government’s target of P27 pesos per kilogram, which it promised would be reached after the NFA released 3.6 million 50-kilogram bags of rice to local markets last September.

Ofracio recognizes the interrelation of the plight of farmers and the urban poor under the liberalized rice trade regime. “The urban poor stands in solidarity with our farmers in denouncing the RLL,” he proclaimed during his protest speech.

Women and children bear the brunt

Rural women and children pay the highest price as the impacts of RLL continue to aggravate conditions of poverty and hunger in the countryside.

“Increased poverty has forced children to drop out of school,” lamented Meth Jimenez, Secretary General of Kasarinlan Kalayaan (Gender Freedom) or SARILAYA. Meanwhile, women have been “forced to leave their homes and venture into urban areas in search of higher-paying jobs, with many of them becoming vulnerable to trafficking.”

A national concern

The havoc wrought by the RLL on the local rice industry, however, is not just a concern of small-scale farmers and poor consumers but of the entire country.

Given that local rice farmers supply 90 to 95 percent of the country’s rice requirements, their welfare and that of the entire rice industry is crucial in ensuring national food security, economic well-being, and political stability.

“The RLL poses a great threat to our nation’s food security,” warned Tadeo. “If we run into a shortage of rice supply in the world market, where will our importation policy take us? Where will we get our staple crop if the RLL has already impoverished our farmers and forced them to sell their lands to be primed for conversion?”

Jimmy Tadeo delivers a solidarity message and explains the impacts of the RLL on local rice production. 2019 November 20. Pasig City, Philippines.

Tadeo further claimed that by killing rice farmers, government policies are dragging down the national economy. “The life of our farmers is the life of this country. If our farmers are prosperous, the Philippines will progress. But by destroying the livelihood of our farmers with its economic policies, the government is also hampering the development of our country.”

Rice continues to account for around 20% of the gross value added (GVA) of Philippine agriculture. Furthermore, data from the Food and Agriculture Organization reveals that 2.5 million Filipino households continue to rely on rice production as their main source of income.

Farmers’ demands

In light of the devastating outcomes of the RLL, opposition groups comprised of farmers and other major stakeholders in the rice industry have laid down a clear set of short, medium, and long-term demands.

Recognizing the immediate need to mitigate the impacts of the RLL, the groups call for its prompt suspension, a comprehensive review of its effects on the rice industry, and the provision of compensation for the losses that farmers and stakeholders have incurred because of the law.

The groups also call on Senator Cynthia Villar, main sponsor of the RLL, to step down as Chairperson of the Senate Committee on Agriculture. Her involvement in a family-run real estate business that actively engages in land conversion has precipitated a conflict of interest that has jeopardized the wellbeing of the local rice industry.

In the longer term, the groups are demanding the government to repeal the RLL; strengthen state support for rice trade through the provision of subsidies, irrigation, and infrastructure; increase the procurement capacity, drying and storage facilities, and outreach of the NFA; and incentivize the formation and expansion of agricultural cooperatives.

To end the program, protesters stage a “die-in” outside NEDA to symbolize how the RLL is killing farmers, rural workers, and poor consumers. 2019 November 20. Pasig City, Philippines.