By Bianca Martinez

16 September 2021

President Rodrigo Roa Duterte delivers his 5th State of the Nation Address at the House of Representatives Complex in Quezon City on July 27, 2020. PRESIDENTIAL PHOTO

Despite the numerous controversies hounding his administration, Duterte has managed to maintain his popularity through the years. The latest nationwide Pulse Asia survey conducted in September 2020 showed that his approval rating even rose to an all-time high of 91 percent. This defied expectations that Duterte’s ratings would decline due to his administration’s failure to contain the pandemic and cushion its socioeconomic impacts.

Of course, these survey results should not be taken at face value. As journalist Randy David said, survey methods have limitations, and often, the social conditions that may have significantly shaped participants’ answers may not be easily gleaned from the results. One such condition is the culture of fear that has become more prominent with Duterte. A June 2019 SWS Survey showed that 51 percent of Filipinos agree that it is “dangerous to print or broadcast anything critical of the current administration, even if it is the truth.”

But whether Duterte’s ratings reflect support, fear, or both (and to what extent), what remains clear is that these ratings represent crucial information that need to be understood within prevailing political, economic, social, and cultural conditions. Certainly, the question of why Duterte remains popular is complex and does not have one definitive answer. There are multiple dynamic and oftentimes contending institutions and factors that affect any political leader’s popularity, which in turn contributes to shaping people’s perception of their legitimacy. One particularly important factor is the use of language and ideological narratives.

Language is important because, especially when used by those in positions of power, it significantly shapes people’s thoughts, opinions, and even their behavior. As linguist Vassil Hristov Anastassov had argued in his important work on the power of language and narratives in shaping political discourse, there is always a stronger side in communication that dominates with its “will to power.” Language, being the currency of communication, is thus inherently political, and it has a persuasive force that perpetuates unequal power.

At the same time, however, it is important to note that those who confer support to Duterte are not simply duped by his charisma. Often, their support is based on moral calculations shaped by their values, fears, and aspirations, which in turn are influenced by their unique experiences and the prevailing social conditions within their social spaces.

Contextualizing the Duterte government’s dichotomous narratives, networked disinformation, and violent rhetoric within prevailing social conditions that underpin support for Duterte, it becomes clear that the damage inflicted by Duterte’s language has been to tap into people’s frustrations and fears and bring out the most callous facets of our dominant cultures in order to enable his fascist rule.

Driving demand for punitive justice

The first damage that Duterte’s language has done is to incite a more violent sense of “othering” that creates a demand for punitive justice.

Since the 2016 presidential campaign, the central narrative that has made Duterte popular and eventually propelled him to the presidency is that the proliferation of illegal drugs in the Philippines is a national crisis that, if left unchecked, will eventually destroy the country. This narrative of crisis has effectively invoked anxiety and fear among the people, dichotomized “righteous” citizens and unscrupulous drug users and criminals, and inflated public demand for punitive justice and harsher mechanisms of social control.

Once this demand was created, Duterte elevated the drug crisis as a national security issue, allowing him to tap the coercive instruments of the state. Wielding people’s demand and the state’s coercive power, the Duterte administration institutionalized the “neutralization” of alleged drug users and peddlers under the war on drugs. When criticized for the campaign’s violence and disregard for due process and human rights, Duterte insisted that such considerations will only slow down the process. In his books, real change requires a strongman approach, and often the price is our fundamental rights and freedoms.

One of the reasons that Duterte’s narrative of crisis and his bloody approach worked is that even before he foregrounded the drug problem as a national crisis in 2016, many Filipinos had already recognized and felt its impact in their own local communities. But as sociologist Nicole Curato had argued in her ethnographic research on the everyday articulations of political support for Duterte’s war on drugs, the problem had previously remained “latent” in the sense that it never “[warranted] the sustained attention of the state” and was “never solved with finality,” as most solutions were limited to community-level responses.

When Duterte introduced the drug crisis narrative, what he did was to foreground a previously latent but nevertheless important issue and incite violent othering as the response. This was widely accepted even among many non-Duterte supporters, showing just how prevalent the violent othering of drug users was.

But the Duterte administration’s use of a dichotomous narrative that incites violent othering is not limited to the war on drugs. In fact, it is front and center in the fascist playbook. We have seen the government replicate this in its blunt-force approach to environmental problems and its enforcement of a militaristic response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In all these cases, the Duterte administration’s narrative depicts certain people or groups as existential threats—the coastal communities that “litter Manila Bay” and the “undisciplined” citizens that spread coronavirus. In this sense, the state creates consensus for imposing brute force by exploiting and exacerbating people’s aversion to the difference of the intrusive and dangerous “other.”

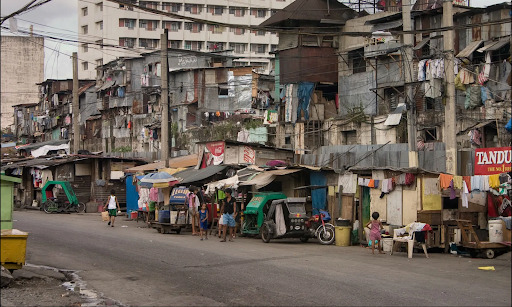

Underpinning people’s support for the use of authoritarian measures to address social issues is the popular belief that Filipinos are inherently undisciplined and unruly (in Filipino, this is referred to as pasaway). Such attributes supposedly hinder the country’s economic, political, and social progress. Within this narrative, the pasaway is thus made to embody an existential threat that needs to be disciplined. In popular discourse and policy-making, the image of the pasaway is often informed by deep-seated class prejudices, which deem the poor’s way of living as destructive and regressive. This makes poor people the disproportionate target of hostile and abusive policing that supposedly aims to maintain order and discipline.

The urban poor are often portrayed as the archetype of the pasaway. Photo source: Anton Zelenov, Wikimedia Commons.

Beyond class prejudices, the pasaway archetype has also been informed by Duterte’s highly divisive political narrative. With Duterte conveying that his interests are equated with the interests of the nation, he has made it seem that anyone against him is against the nation. Following this premise, the term pasaway has thus also been used to pejoratively describe dissenters and activists criticizing Duterte’s authoritarian rule.

Demonizing human rights

While human rights movements were scrambling to consolidate their rights-based counternarratives and alternatives to Duterte’s strongman rhetoric and approach, the Duterte administration had already effectively tarnished the concept of human rights by spreading disinformation narratives insinuating that human rights defenders, activists, and other critics of the administration’s anti-drug campaign are oblivious to the daily brutalities of crime and drugs and are more concerned about the wellbeing of criminals than those of their victims.

As progressive forces became more vigorous in exposing the impacts of the administration’s systematic human rights violations on different sectors and communities, so has the state geared up its physical and ideological assault against all forms of dissent. Duterte, his mouthpieces in the government, the police, and the military institutionalized and legalized the malicious tagging of human rights defenders as communists and terrorists, thereby further discrediting them and exposing them to state violence.

Many bought into these narratives not because they are passive dupes but because these narratives resonate with their own frustrations with due process, human rights, and liberal democracy and aversion to communism. For many Filipinos that have been caught in the middle of wars, crime, land grabbing, and development aggression, violence has long been a part of their everyday lives, and the concept of human rights has been rendered meaningless whether in times of liberal democracy or dictatorship. As such, for many of these people, Duterte’s mockery of human rights and the “politics of decency” as embodied by the Aquino administration comes as a breath of fresh air. As sociologist Walden Bello had aptly put it, the deliberate political incorrectness of Duterte’s discourse “comes as very liberating to the middle- and lower-class audience because it is seen as mocking the rhetoric of human rights, democratic rights, and social justice, which have not been delivered over the last 30 years. It comes across as anti-hypocritical.”

Additionally, in an interview with Joseph Purugganan, Josua Mata and Rose Trajano also point to the lack of appreciation for human rights (especially economic, social, and cultural rights) among the general public as one of the main reasons why Duterte was easily able to corrupt the concept in the first place. This is an important point of reflection for progressive organizations, as it reflects the gaps in the human rights education work.

Deflecting thoughtfulness, restricting imagination

The Duterte administration’s systematic and constant barrage of disinformation in the form of absurdities, deliberate ironies, misleading data, gaslighting, red-tagging, and simplistic narratives, among others, have effectively imploded the distinction between true and false, deflected thoughtfulness (which is very necessary to political action), and further stymied the public’s capacity to engage in critical discourse and imagine more humane and just alternatives.

Of course, spreading pro-government propaganda and disinformation is not a new tactic. It has always been a part of any sitting government’s ideological arsenal to control the dominant political narrative and maintain power. However, with Duterte, this has taken a more vicious turn. His administration has unscrupulously wielded state powers, functions, and resources (including Duterte’s almost nightly public addresses, Malacañang press briefings, traditional media, and social media) to spread disinformation, with the goal of fomenting divisiveness, inciting and legitimizing violence against the perceived “other”, delegitimizing and silencing dissent, and evading accountability.

Public addresses

There are different methods and platforms through which the Duterte administration has inundated the public with disinformation. One of these is through government officials’ public addresses and statements, delivered primarily through traditional and digital media usually in the form of soundbites. The predominant use of speech over written words lends to the government’s manipulation of the truth. As Stephen J. Rosow had said in his foreword to Anastassov’s work, the instantaneous and fleeting nature of speech itself delivered primarily through soundbites by the media eliminates time as duration for critical thinking and allows little to no questioning, thereby deflecting thoughtfulness. As such, “if nothing matters but the immediate locution, the response can be little but an emotional, unthinking affirmation or rejection.”

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, these addresses have become even more frequent as the situation demanded regular communication between the government and the public. Duterte and his cronies took advantage of this situation and their prominent positions as the mandated communicators of the government to intensify their disinformation campaign.

Undermining meaning. One of the most common tactics deployed by public officials is to undermine the meaning of certain words either to corrupt them, conceal their negative connotations, or paint a rosy picture of an otherwise bleak situation. For instance, when responding to the Commission on Audit’s (COA) report flagging deficiencies in the Department of Health’s (DOH) use of P67 billion worth of COVID-19 funds, Duterte angrily ordered COA to stop flagging government agencies as this was tantamount to “flogging.” He painted COA’s constitutional mandate for checks and balances as a threat, saying that it puts agencies and individuals in a bad light by creating a taint of “corruption by perception.”

This is the same tactic used by the administration to justify its blunt-force approach: it depicts due process and human rights as instruments that defend criminals and thus hinder justice for the aggrieved victim. Following this premise, swift justice thus necessitates bypassing and undermining these democratic institutions.

Numericizing and cherry-picking. Apart from undermining words, some prominent public officials in the government have in many cases reduced the discourse on social issues into numbers and quantitative parameters. In this discourse, they have often cherry-picked data leading to conclusions that put the government’s pandemic response in a good light, in sharp contrast to the reality on the ground. For instance, the government and its supporters recently celebrated the “11.8 percent growth” of the GDP during the second quarter of 2021, claiming that it signified the end of economic recession. However, an economist exposed that this result was arrived at through a “mathematical illusion” where the GDP during the second quarter of 2021 was compared to that during the second quarter of 2020 (one of the lowest points of our economy), naturally leading to a high percentage increase.

The same tactic was used by Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque when he claimed in a press briefing last August 24 that the government’s COVID-19 response was effective given that the daily COVID-19 case count was still “below the projected 25,000 cases per day” as calculated by experts—completely disregarding the fact that daily cases then had already breached the peak during the second wave.

By focusing on quantitative parameters, the government dehumanizes the impacts of COVID-19 and erases the faces and struggles of COVID-19 patients, their families, and healthcare workers reeling from the impacts of an overwhelmed healthcare system.

Gaslighting and red tagging. As different sections of civil society protested against the government’s mishandling of the pandemic, prominent public officials (including no less than the president) resorted to gaslighting and red-tagging. One concrete example of political gaslighting is when the Department of Health (DOH) responded to healthcare workers’ plan to hold a mass protest by appealing to them to defer such actions as these would “strain the health care system and hospital operations.” DOH Spokesperson Maria Rosario Vergeire said, “Let us give way to caring for our patients.” To healthcare workers, statements like these tell them that inhumane working conditions come with the territory. To the public, they gloss over the legitimate reasons that compel healthcare workers to protest in the first place despite difficult circumstances.

Last year, Duterte threatened and taunted healthcare workers who held a protest to demand the government to give them a timeout by reverting to stricter community quarantine. He said, “Do not go out shouting for a revolution…If you say revolution, do it now. Go ahead. Try it. Let us destroy our nation. Let us kill all those who are infected with COVID.” At the end of his address, he said: “That [revolution] is more dangerous than COVID. If you wage a revolution, you will give me a free ticket to stage a counterrevolution. How I wish you would do it.”

Simplistic narratives. The Duterte administration’s simplistic narratives and instrumentalization of people’s suffering erase the systemic roots of certain issues and allow the government to sidestep accountability. A concrete example of this is the war on drugs, where Duterte points to the drug problem as the cause of rape, sexual harassment, and other crimes. By doing so, he erases the political, cultural, and socioeconomic roots of said problems.

As to the pandemic, the Duterte government has falsely dichotomized public health and economic recovery, insisting that it can only prioritize one over the other. Contrary to what Roque said in his recent outburst that the government is trying to strike a balance between the two, their decision to loosen community quarantine restrictions despite swelling cases and an overwhelmed healthcare system clearly shows that they still favor economic recovery.

In further trying to justify the government’s decision, Roque, Edsel Salvana (pandemic task force adviser), Vergeire, and other officials explained that the government is only concerned about the poor, jobless, and hungry who have borne the brunt of the lockdown. But they conveniently left out the fact that the main reason people are suffering under strict lockdown is that the government has refused to provide sufficient aid to the people and has not taken the appropriate steps to improve the capacity of our weak healthcare system—despite having the resources to do so. Instead, what the government has done is to stand firm on maintaining fiscal discipline and insist that reopening the economy and expanding vaccination are our only way out of the pandemic, while handing the reins on economic recovery over to the private sector.

These are just some of the disinformation narratives employed by the government. It does not help that many of their statements—regardless of how senseless, absurd, or harmful—are often extensively covered and uncritically presented to the public by most traditional media. Meanwhile, alternative perspectives and approaches are rarely put in the spotlight. This is detrimental to people’s right to information (which is also foundational to the realization of other rights) considering that many Filipinos rely on broadcast media as their main source of information due to the inaccessibility of privatized internet services.

Disinformation in the digital space

Another equally important platform through which the government spreads disinformation is the digital media. With Filipinos being the most active social media and internet users worldwide, many have become vulnerable to disinformation campaigns. Forming the backbone of these campaigns are social media influencers and “troll armies.” Studying this phenomenon, Jonathan Corpus Ong and Jason Vincent Cabañes uncovered the professionalized, hierarchized, and financially incentivized network of digital workers who design, strategize, and execute online disinformation campaigns.

The aim of the “architects of networked disinformation” is to circulate narratives that stir up grassroots support and harness the zeal of “real” or unpaid political supporters to willingly spread these narratives within their own social spaces.

To this end, strategists from the advertising and public relations industry tapped by political clients transpose tried-and-tested ad and PR strategies to create effective political campaign goals and core messages; social media influencers weaponize their fluency in popular vernaculars to translate core messages into attention-hacking content that can mobilize public sentiment; and fake account operators echo these messages and post a prescribed number of scripted posts and comments, thereby creating “illusions of engagement.”

These digital workers employ a range of disinformation strategies, such as artificially making certain topics or messages trend, preventing the opposition’s messages from trending through signal scrambling, positive branding of political clients, and smear campaigns against political opponents by using populist language (e.g., bringing up divisive issues, appealing to a community of discontent, evoking a state of crisis, and using vulgar language).

The amplification of artificial engagement encourages organic engagement from unpaid grassroots intermediaries and “real” supporters who not only amplify original campaign messages but often give them a more malignant twist, peppering their messages with misogyny, homophobia, violence, and other forms of hate speech.

The ubiquitous and constant barrage of disinformation that stokes fear, anxiety, anger, and frustrations towards a defined existential threat makes it difficult for people to trust themselves, to make informed opinions based on factual truths, and to make sense of their reality. In weakening our ability to rely on our own mental faculties, we lose our common sense and are forced to rely on the judgments of others. This phenomenon is what George Orwell has popularly referred to as “doublethink,” a state of cognitive dissonance in which one is compelled to disregard their own perception in place of the officially dictated version of events, leaving the individual completely dependent on the state’s definition of reality itself.

In turn, losing our ability to make meaning freely from our experiences constricts our ability to engage in political action. As Hannah Arendt had said in her compelling classical essay “Lying in Politics,” action—by its very characteristic of always beginning something new—necessitates the capacity to “imagine that things might as well be different from what they actually are” in order to push us to change “things as they were before.” Political lies restrict such imagination by forcing us into an unthinking state that makes us accept the status quo. Ultimately, the restriction of our ability to think and consequently to act further weakens our country’s already fragile democracy.

Culture of solidarity and resistance

In sum, Duterte’s violent rhetoric has damaged democracy by legitimizing the use of state violence in order to achieve “meaningful change”; tarnishing the concept of human rights to the point that it elicits fear when used in political discourse; and subverting our ability to think (beyond the dictates of those in power, against forgetfulness, and from the point of view of the other) and imagine more humane, just, and democratic alternatives, and to act towards the realization of those imaginaries.

It is important to point out, however, that the aftermath of Duterte’s violent rhetoric on our political culture is not necessarily a radical departure from prevailing cultures. The seeds of Duterte’s penal populism and resultant violent othering have long been implanted by individualism, classism, authoritarianism, political idolatry, clientelism, and an overall lack of appreciation for the concept and everyday practices and manifestations of democracy and human rights (not only in the realm of politics but also in economics, society, and culture). Essentially, what Duterte has done is to make more visible the cracks in our culture. These regressive cultures, which inarguably played an important role in the rise to power of a fascist like Duterte, are shaped by dominant economic and political systems and by our historical experiences as a nation.

Thus, the long-term and painstaking task at hand is to work towards changing those cultures and their systemic roots and promoting a culture of solidarity and resistance. It is a daunting undertaking, but some of the important steps towards this are already being done by various grassroots communities, social movements, and civil society organizations through the creation of counter narratives, political education, and community organizing.

A community pantry set up in Camaligan, Camarines Sur in the Bicol Region. The sign reads: “Give whatever you can, take only what you need.” Photo source: Anthony B. Diaz, Wikimedia Commons.

Amid the pandemic, as millions lost their jobs and livelihoods and were left by the government without sufficient aid, different communities took it upon themselves to help one another in the true spirit of bayanihan (solidarity). One of the things that bound people together in these trying times was food. Travel restrictions disrupted the fragile global food supply chain, severing access to food of millions who have been forced by the system to depend on international trade for food security and livelihoods. In response, farmer communities from different provinces initiated or reinvigorated agroecological practices and seed banking and set up local markets to strengthen their collective resilience and food self-sufficiency. Some worked with civil society organizations to facilitate the delivery of their produce directly to urban consumers. In the Municipality of Lebak where people are bearing the impacts of both the pandemic and ongoing conflicts, tri-people communities (Bangsamoro, Lumad, and migrant settlers) pooled together voluntary contributions and resources to establish the collectively operated “Kusina Bayanihan” (or community solidarity kitchen), which provides community members with cooked meals. Across the country, grassroots-led community pantries that provided people with bags of rice, vegetables, canned goods, face masks, and other essentials have sprouted since April 2021. Premised on the idea of giving what you can and taking only what you need, the initiative was aptly described as a form of “mutual aid.”

Apart from food, art has also played an important role in unifying people in these trying times. Progressive cultural activists have used various forms of art to raise political consciousness as well as to promote a deeper understanding of complex political issues. These artistic expressions, especially when they communicate the struggles and triumphs of the masses, have the great power of eliciting compassion and linking people in different ways. Various artists have performed or created poems and songs that bare the different forms of injustice in our society and evoke social consciousness, contemplation and thoughtfulness, reason and compassion, and unity and determination to fight back and hope for a better future. Here, we witness and harness the creative power of language, not to concoct lies and deceive as what the ruling classes do, but to help us rethink communal life according to more democratic imaginaries and enable freedom.

______

#Duterte and the Damage Done is a series of opinion pieces from Focus staffers in the Philippines reflecting on key concerns that underscore the damage that the Duterte administration has inflicted on the nation