Originally published here. Written for Amplifying Human Rights Through Music: A Tribute to the UDHR (Asian Village Zine #4).

“In order for me to write poetry that isn’t political,

I must listen to the birds

and in order to hear the birds

the warplanes must be silent.”

(Marwan Makhoul, Palestinian poet)

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the adoption of the Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, that laid down for the first time an “international legal framework entirely dedicated to the protection of cultural heritage (UNESCO) in times of conflict.

Sadly, 7 decades on, conflicts pervade across the globe and cultures are relentlessly under attack. Wars and violent occupations have not only destroyed cultural heritage, defined by UNESCO to include both “tangible heritage such as artefacts, monuments, a group of buildings and sites, museums, and intangible cultural heritage embedded into cultural, and natural heritage artefacts, sites or monuments,” but have threatened the artists themselves, especially those at the frontlines of people’s struggles, and have diminished the spaces for people to create, share and to freely participate in the cultural life of the community as enshrined in Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

The genocide in Gaza that is happening right before our eyes (“the first genocide livestreamed”), has injured close to 100 thousand people , and taken the lives of more than 44,000, mostly women and children, and the death toll continues to rise by the hour. We are also witnessing In Gaza, a continuing ‘cultural genocide’, with the total destruction or damage to “nearly 200 sites of historical importance in Israeli air raids on the Palestinian enclave’ in the first 100 days of the on-going genocide.

2024 is indeed a “a year scarred by conflict”. The State of Artistic Freedom report 2024, reports on the various ways by which artistic freedom was laid under siege- from censorship to criminalization, from incarcerations to killings,

In Southeast Asia, SAF 2024 reports a total of “625 violations against artistic freedom recorded from 2010-2022 in several Southeast Asian countries, a pattern that continued into 2023.” The situation in the region is characterized by a deadly mix of “political instability, military coups, armed conflict and democratisation setbacks.” The report highlights the various ways by which censorship was instituted “from state entities and government regulatory bodies reaffirming and negotiating different forms of fundamentalism.”

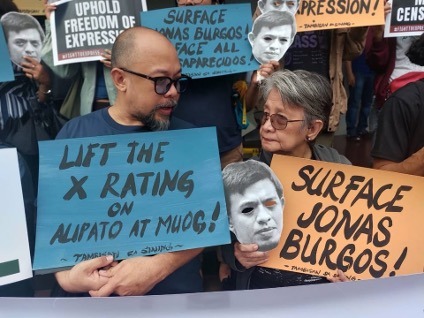

Attacks against filmmakers were particularly pronounced in the region, with a total of 172 documented cases of rights violations. Several films delving on various social issues like prostitution, inter-faith dialogue, and enforced disappearance were banned and censored and the filmmakers charged with mostly trumped up charges.

A more recent case was the X-rating by the Movie Television Review and Classification Board (MTRCB) in the Philippines of the documentary Alipato at Muog (Flying embers and a fortress) by independent filmmaker JL Burgos. Alipato at Muog is a film about the enforced disappearance of the filmmaker’s brother the activist Jonas Burgos in 2007 and the continuing search of the Burgos family. The filmmaker and the producers challenged the decision leading to a reversal of the x-rating and lifting of the ban.

That too must be the story of 2024 in the context of culture and conflict, the unwavering commitment of people to exercise their rights to free speech, to express themselves through culture and arts, and to resist and push back against forces that aim to silence or derail their efforts. To persist and flourish in the midst of conflict.