Position Paper of In Defense of Human Rights and Dignity Movement (iDEFEND) on the proposed law on Corporate Social Responsibility.

In Defense of Human Rights and Dignity Movement (iDEFEND) humbly submits to the Senate Committee on Trade, Commerce, and Entrepreneurship our comments to proposed Senate Bill 2355 or the Corporate Social Responsibility Act.

1. CSR and State Policy

The recently approved House Bill 451 or the Corporate Social Responsibility Act and its pending counterpart in the Senate, Senate Bill 2355 aim to encourage businesses to observe corporate social responsibility in their operations. The bills in both Houses of Congress draw their mandate on the State’s recognition of the vital role of the private sector in nation-building and why their active participation in fostering sustainable economic development and environment protection should be encouraged.

The Constitutional basis of corporate social responsibility, however, extends beyond the provision cited in the proposed law of the State’s recognition of the role of the private sector (Article II Section 20), and delves on the principle of social function of private property and enterprise.

Article XII Sec. 6 states that “the use of property bears a social function, and all economic agents shall contribute to the common good. Individuals and private groups, including corporations, cooperatives, and similar collective organizations, shall have the right to own, establish, and operate economic enterprises, subject to the duty of the State to promote distributive justice and to intervene when the common good so demands.” (emphasis supplied)

We argue that the duty of the State to regulate corporations in the interest of the common good should be the starting point of the proposed law on corporate social responsibility. As it currently stands, SB2355 presents a narrow view of State policy when it comes to State-Business relationship as a mere provider of incentives to corporations to encourage the practice of CSR.

2. CSR has been practiced, numerous incentives in place but need to be assessed towards crafting a stronger policy

CSR practice in the Philippines, in fact, has been observed since the 1960s. A study on CSR in the Philippines by the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC 2005) describes the evolution of CSR across the decades: from the decade of donations in the 60’s, the establishment of business organizations in the 70’s, involvement in the provision of services like community relations in the 80’s, institutionalization of policies on corporate governance in the 90’s, and continued improvement in the 2000s as corporate foundations continued to push for greater participation in improving access to basic services.

One of the main findings of a survey conducted in 2012 by Newsbreak commissioned by the League of Corporate Foundations and participated in by 80 of the largest corporations in the country, was that “most of the CSR activities were still mainly philanthropy and event-driven, but employee volunteerism has become more prominent in the CSR designs.”

An assessment of CSR practice in the country is in order to see whether it has evolved further away from philanthropy and event-driven activities. For example, the Aboitiz corporation spelled out the evolution of their CSR policy, to wit: “From a legacy company that was big on philanthropic deeds, our corporate social responsibility has evolved into co-creating resilient, empowered, and sustainable communities.” Corporations like Sagittarius Mines, Inc (SMI), another example, is already projecting a ”commitment to ethical behavior” and adherence to UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP).

In other words, the proposed law should take cognizance, as well, of how CSR practices in the Philippines have evolved in order to determine whether compliance to a minimum standard like CSR is still the way to go when it comes to how States should regulate corporate behavior.

Rationalizing Fiscal Incentives

The heart of SB2355 and the main strategy to encourage the practice of CSR is outlined in Section 4, on deduction from unrestricted earnings, which proposes an amendment to the corporation code to allow corporations to retain surplus profits in excess of 100% paid-in capital stock to support CSR projects and programs.

The Committee should examine this proposed incentive in light of the following:

There is a whole range of fiscal incentives that are already in place to encourage the practice of CSR. In the context of continuing reforms to rationalize fiscal incentives, it would be important for the committee to consider the amount of government revenue that will be lost as a result of this amendment.

It is also important to look at how effective these incentives are to encourage CSR. As pointed out by the Philippine Business for Social Progress (PBSP), “incentives per se could not convince companies to conduct CSR because to begin with, incentives are tied up with other laws, such as the Clean Air Act of 1999 (Republic Act 8749) and the Agriculture and Fisheries Modernization Act (Republic Act 8435). Therefore, the main objectives are not geared towards improving CSR activities.”

Perhaps for the bigger companies that have already well established CSR practices, another issue is that of redundancy of incentives. A study by Reside in 2006 found that a large amount of incentives being provided to corporations are redundant: “they are given to many firms that would have invested anyway without them.”

A key question, therefore, is whether incentives should be given to companies that are already implementing CSR projects or are these better reserved or targetted to companies that have yet to do so?

In relation to these two issues — effectiveness and redundancy — rationalization of incentives for CSR purposes should also be considered in terms of how we make these incentives time-bound, performance-bound, and transparent.

3. CSR and human rights: the importance of legally binding rules

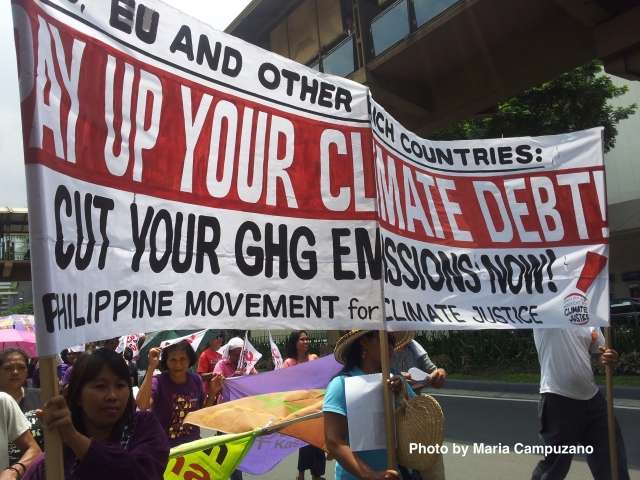

Major companies operating in the country with substantial CSR programs continue to support the perpetration of human rights violations and the destruction of the environment.

The Philippines continues to be one of the most dangerous countries in the world for human rights, land, and environmental rights defenders (HRDs). In its 2022 report, Defending Tomorrow, Global Witness noted a rise in the number of attacks against HRDs in the country from 30 killings in 2018 to 43 in 2021.

Many of these lethal attacks against rights defenders are associated with large scale investments in the mining, agribusiness, logging, water and dam sectors. In its 2019 report on the Philippines, Global Witness warned that “mining, agribusiness, logging and coal plants are driving attacks against environmental activists – with household brands such as Del Monte Philippines and Dole Philippines, and Filipino giants like San Miguel Corporation linked to local partners accused of attacks and murders of protestors.”

There are cases where CSR merely serves as a public relations tool for companies and thus “do not really intend to benefit the local community, but merely to bolster the company’s image.”

Contradiction between CSR and Human Rights: The case of OceanaGold Philippines, Inc’s Didipio Mine

When a number of large corporations with strong CSR programs, with well articulated goals on social responsibility, ethical practice, and community development themselves face serious complaints of human rights abuses in their business operations, this highlights the weakness of the CSR framework.

Oceana Gold Philippines, Inc (OGPI) is the Philippine subsidiary of Australian-Canadian gold and copper mining company operating the Didipio Mine in Kasibu, Nueva Vizcaya. In its website, Oceana Gold reports various programs aimed at supporting the communities within its mining operations in such areas as health, education, infrastructure and capacity building. “Between 2013 and 2018, the Didipio Mine has reportedly invested over PHP 39.5 billion (US$790 million). Of this expenditure, 96 per cent (PHP 38.3 billion) was paid to employees, government and businesses through salaries, taxes and procurement while PHP 1.2 billion was spent for community development.”

In February 2019, “several Special UN Mandates sent a joint communication to the Government of the Philippines and Oceanagold company highlighting their concerns over the environmental impact of the company’s activities and the lack of consent of indigenous and local communities for the mine to operate on traditional lands.” Subsequently, the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights also took issue over the forcible dispersal of “some 30 indigenous and environment defenders who were blocking three fuel tankers from entering Oceanagold Didipio mining site in Nueva Vizcaya province.

In response to these letters and public statements , the company asserted that it “stands by (its) commitments to responsible mining and will continue to engage openly,” and its focus remains on “continuing to work in partnership with all our stakeholders to recommence responsible mining at Didipio as soon as possible.”

There have also been instances where CSR projects have been used as leverage to stifle community opposition to the project.

With its million-peso investment in CSR through the years, OGPI has been able to perpetuate itself in Brgy. Didipio, despite strong resistance from the community. On June 3, 2022, the Barangay Council passed Resolution No. 38 which expressed the council’s opposition to the renewal of OGPI’s Financial or Technical Assistance Agreement (FTAA) for another 25 years, citing the failure of the national government and OGPI to consult the barangay and community prior to the renewal, including lack of assessment, audit and evaluation of OGPI’s 25 years of mining activity. However, the President of OGPI, according to community reports, berated the barangay officials and threatened to withdraw the funds the company provides for the salaries of teachers, scholarships and other community projects. Soon after, the council passed Resolution No. 61 which revoked in its entirety Resolution No. 38.

Evolving Business and Human Rights regime

Just as the practice of CSR has evolved, so must the nature of the State’s relationship with the corporate sector. CSR should be examined as part of the existing legal framework at the national and international levels on the regulation of business activities, particularly in relation to the impact of businesses on human rights and on the environment. Furthermore, the State should provide for safeguard against possible abuses of corporations of a CSR Law.

CSR and Business and Human Rights (BHR)

In 2011, the United Nations Human Rights Council adopted Resolution 17/4 endorsing the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP).

The UNGPs are a set of 31 principles directed at governments and businesses that clarify their duties and responsibilities in the context of business operations. According to the UNGPs:

- Governments have a duty to protect everyone within their jurisdiction from environmental and social impacts caused by business practice;

- Businesses have a responsibility to avoid environmental and social impacts wherever they operate and whatever their size or industry, and address any impact that does occur;

- When environmental and/or social impacts occur, both governments and businesses have a duty/responsibility to support victims to access effective remedies through judicial and non-judicial grievance mechanisms.

Although CSR and BHR are both voluntary mechanisms, there are also differences between these two approaches. As one international legal expert Anita Ramasastry put it: “While CSR emphasizes responsible behavior, BHR focuses on a more delineated commitment in the area of human rights. BHR is, in part, a response to CSR and its perceived failure.”

Demand for Stronger Regulations

SB 2355 is a policy proposed to promote environmental protection and yet, its current provisions fall short in terms of encouraging mitigation of businesses’ impacts to the environment and promoting environmental protection.

Corporations are being called upon to increase their involvement in the country’s economic recovery efforts as well as in contributing solutions to worsening challenges such as disaster and climate threats. At the same time in the context of rising power of corporations and the alarming increase in the number of human rights abuses driven by them, and continuous effect on the environment, the situation calls for a much stronger response from the State to regulate businesses. The State, through measures like SB 2355, more than providing incentives, must exact corporate accountability for the environmental impact and the human rights abuses committed in the course of their operations.

Human Rights Due Diligence

As noted by the Business and Human Rights Resource Center: “Under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, companies have a responsibility to undertake human rights due diligence.” Yet a decade after their adoption, benchmarks and analyses demonstrate low levels of commitment: almost half (46.2%) of the largest companies in the world analyzed in the latest Corporate Human Rights Benchmark failed to show any evidence of identifying or mitigating human rights issues in their supply chains.

BHRRC further noted however “the growing momentum worldwide among governments, particularly in Europe, to require companies to undertake human rights and environmental due diligence, from the French Duty of Vigilance Law and the adoption in 2021 of new laws in Germany and Norway to the publication of a proposal for an EU-wide law in 2022. Major investors and companies are also speaking out in favor of such legislation.”

Philippine Position on the Legally-Binding Instrument (LBI)

Another crucial development in the area of corporate accountability on human rights was the adoption in 2014 of the UN Human Rights Council Resolution 26/9 “to establish an open-ended intergovernmental working group on transnational corporations (TNCs) and other business enterprises (OBEs) with respect to human rights, whose mandate shall be to elaborate an international legally binding instrument to regulate, in international human rights law, the activities of transnational corporations and other business enterprises.”

The Philippines was one of among 6 Asian states that supported the adoption of Resolution 26/9, and it has been an active participant in the negotiating sessions that were initiated in 2015.

At the 8th session of the Open-ended Intergovernmental working group on TNCs and OBEs, the Philippines made these statements indicating its commitment to supporting the process towards a robust legally binding instrument to regulate TNCs:

“As one of the 20 countries that voted in favor of HRC resolution 26/9 of June 2014 which established the Working Group and its mandate, the Philippines reaffirms its support for this process (emphasis supplied). We thank the Chair for reflecting a number of recommendations and proposals made by the Philippine delegation, particularly on Articles pertaining to legal liability and the definition of victims. However, we are concerned that the heart of the mandate of HRC resolution 26/9 which expressly limits the scope of the LBI to the activities of TNCs and OBEs, remains unaddressed, diffusing the focus of the LBI instead on all businesses.”

In the LBI negotiations, there is an ongoing debate already on whether corporations, in fact, should have human rights obligations beyond the “responsibility to respect” outlined in the UNGP. Civil Society organizations and networks like the Global Campaign advances the case for concrete obligations for transnational corporations in international human rights law that are distinct from the obligations of States:

First, States jointly establishing concrete obligations to TNCs at the international level reflects just another way of them collectively exercising their regulatory power as representatives of the peoples.

Second, these obligations will be of extreme relevance to support States regulating TNCs at the national level, giving them the upper hand when facing power asymmetries and circumventing corporate capture.

Finally, establishing concrete obligations to TNCs in International Human Rights Law is a means for States to fulfill their obligation to cooperate internationally to create an enabling environment for the realization of human rights.

4 . Conclusion

iDEFEND asserts that the proposed Corporate Social Responsibility Act must take into consideration the following issues:

- It should be framed around the duty of the State to regulate corporations in the interest of the common good as the starting point of the proposed law on corporate social responsibility;

- Because CSR is not new and many corporations are already practicing it, there is a need to assess how this practice has evolved over the years to determine whether the policy being proposed is still relevant;

- At the heart of the proposed law is the incentive to be provided to corporations by way of the amendment of the Corporation Code to allow companies to retain surplus profits in excess of 100% paid-in capital stock to support CSR projects and programs, this incentive should be examined closely in terms of (a) how much revenue loss will be absorbed by the government because of this amendment; (b) rationalization of fiscal incentives to determine if these incentives are even necessary;

- In relation to the issues of effectiveness and redundancy of incentives for CSR purposes, the committee should also include in the proposed law ways in order to make incentives to encourage CSR time-bound, performance-bound, and transparent;

- Just as the practice of CSR has evolved, so must the nature of the State’s relationship with the corporate sector. CSR should be examined as part of the existing legal framework at the national and international levels on the regulation of business activities, particularly in relation to the impact of businesses on human rights. CSR now represents a minimalist approach to how the State should deal with corporations and their role in society. Even the current BHR standard is already being challenged in favor of stronger and binding mechanisms for corporate accountability, and the Philippine government has positioned itself in support of this process for a legally binding instrument;

- In the context of rising cases of human rights abuses, and the current environmental crisis, CSR is not enough. We demand corporate accountability.

In Defense of Human Rights and Dignity Movement

23 August 2023

Contact information:

Joseph Purugganan

IDEFEND- Social Justice Campaign Working Group