29 April 2020

Under the Luzon-wide lockdown imposed on March 17 and the subsequent provincial lockdowns, institutions deemed as non-essential have been closed, public transportation halted, mass gatherings banned, and majority of the population ordered to stay at home and observe physical distancing.

To compensate for the lockdown’s negative socioeconomic impacts, the government mandated the distribution of aid to the country’s most vulnerable sectors and peoples. Yet given the weakness of welfare systems in the country, it is not surprising that the lockdown has worsened pre-existing conditions of poverty, hunger, and insecurity. In the community assessment conducted by Focus on the Global South with the help of community organizers, three major issues emerged:

- Repressive implementation of lockdown policies

- Inadequacy or unavailability of relief goods, financial aid, and other forms of government support

- The persistence of state and corporate capture of land, water, and public spaces at the expense of people’s safety and well-being

These conditions have restricted livelihoods, limited access to food and other necessities, worsened hunger, and led to grave violations of civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights. The burden has been heaviest on women who, under a predominantly patriarchal society, are still expected to be the primary caregivers in the family.

“Peace and order” over human rights

Without efficient distribution of adequate support, the repressive implementation of lockdown policies in some communities has severely restricted access to food and food production and led to human rights violations.

Despite the national government earlier clarifying that food-producing sectors can continue to work under the lockdown, representatives of farmers and fishers movements reported that members of their communities have been met with harsh penalties. In some rural areas in the Eastern Visayas region, for instance, people who violate curfew are fined up to PHP10,000, while those not wearing face masks must pay PHP1,000. Violators who cannot afford to pay are counterintuitively detained. Since most farming households only earn an average daily income of PHP330, the hefty penalties have discouraged farmers and farm workers from visiting their smallholdings.Meanwhile, in the Municipality of Limay in Bataan Province, fishers who sailed in the ocean to harvest seafood were detained by authorities. The bail for each person was set at PHP20,000, which is 194 percent higher than their daily income.

On the other hand, Metro Manila-based community organizers recounted how violators of lockdown protocols in some areas of the capitaland adjacent provinces have been intimidated and subjected to inhumane forms of punishment. In the district of Binondo, authorities cut the hair of eight individuals who were caught violating curfew. One of them who resisted was stripped naked and ordered to walk home. Meanwhile, a number of quarantine violators in the nearby province of Laguna were locked in dog cages, with officials threatening to shoot them ifthey refused to follow orders. The national police has also been under fire for its leniency towards a police officer who killed a retired solider by shooting him twice during analtercationin one of the city’s checkpoints.

One of the primary factors that enables district-level authorities’ repressive and violent implementation of the lockdown is President Duterte’s constant promotionofauthoritarian measures to urge people to comply with protocols. In his recent national addresses, Duterte orderedthe national police and local officials to deny aid or arrest people who breach quarantine protocols and shootthose that are inciting chaos.On the delayed distribution of aid, he told people not to challenge the government and just enduretheir hunger for a little longer.Recently, he even threatened to impose “martial law-like lockdown” if protocol violations continue to “surge.”

Underpinning these statements are two extremely distorted premises. One, that maintaining peace and order in the interest of public health and safety comes before individual and collective human rights. Two, that the “unlawful” actions of quarantine violators are mere manifestations of a “lack of discipline”. By superficially depicting these actions as such, the government conceals the reality that in many cases—and especially among the most vulnerable and insecure sectors—breach of quarantine protocols are a consequence of the unbearable conditions that the failing system has forced them into..

The authoritarian approach to addressing the present public health and socioeconomic crisis, however, is not new. It has been the same method used by the Duterte government to address the country’s drug problem.The failures of the anti-illegal drug campaign should have already taught this administration that using an iron hand to address an issue born out of systemic injustice will not work.Yet instead of seeing non-obedience as attempts to escape unbearable systemic conditions that hence demand human rights-based systemic changes, the strongman and his allies pursue the only way they know out of the crisis: to punish and kill. Just like how the anti-illegal drug campaign failed, the reductionist underpinning of the authoritarianlockdown isthereforealso obviously failing to keep people inside their homes and to contain the transmission of the virus.

Irregularities in aid distribution worsen poverty and hunger

What makes it impossible for many to stay inside their homes is extreme poverty and hunger and uncertainties in aid distribution. Narratives from the ground reveal that even after more than a month of lockdown, the government’s socioeconomic relief programs worth hundreds of billions of pesos have still not reached many communities.

For one, the Social Welfare Department’s cash and in-kind support to 18 million low-income households—amounting from PHP5,000 to PHP8,000 per household for each month—does not have a clear and widely disseminated criteria for recipient selection nor a timeline for distribution. Some communities, especially indigenous peoples living in remote areas, have not received any form of aid since the beginning of the lockdown. Second, in communities where aid has been given, in-kind support has been inadequate. Community organizers reported that each family of around five to six members only received three kilograms of rice, six canned goods, and three instant noodles for an entire month. Third, distribution of aid has in many casesbeen based on patronage instead of people’s needs. Some communities that have been resisting government-supported destructive projects have thus been excluded from aid distribution.

Similarly, the support program for displaced workers, farmers, and fishershas also been riddled with problems.On the one hand, labor groups lamented that the Labor Department’s support program for workers is exclusionary, as it only covers workers who are employed by private employers and not informal workers. Another concern is the dependence of aid on employers, who must submit requirements to the governmentbefore their workers can receive aid.[1]

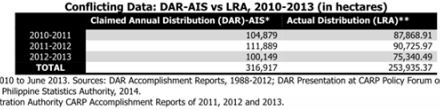

Meanwhile, farmers and fishers lament the delay not only in the distribution of cash aid from the Agriculture Department’s lockdown mitigation measures but also in the implementation of pre-lockdown support programs. According to farmer leaders, they have not been receivingseed and production subsidiesunder the Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund, a PHP10 billion support program to supposedly mitigate the impacts of rice trade liberalization.Meanwhile, some areas reported that they have yet to avail of the department’s loan program, under which small-scale farmers and fishers can borrow PHP25,000. Progressive groups have criticized the loan program, insisting that what farmers and fishers need are subsidies and not more loans as many of them are already heavily indebted.

Plunder of the commons persists

Notwithstandingthe suspension of nearly all public activities, thecompounding socioeconomic crisis, and the absence of a concrete and efficient plan to address the immediate and long-term impacts of the pandemic, the government and big corporations are relentlessly capturing land, water, and public spaces for private gain.

Since February and even well into the lockdown, there have been various reports of fire incidents affecting thousands of families in the urban poor communities in the district of Tondo, Manila. Although the local government reports that these happened by accident, organized residents claim that houses are being deliberately burnedto make way for the construction of a skywayas part of the government’s “Build, Build, Build” infrastructure program.According to one community organizer, the fire incidents have already displaced thousands offamilies amid the lockdown. However, because there is no evacuation center that can accommodate the families, they were forced to pitch temporary shelters along sidewalks using old tarpaulins.

Meanwhile, the construction of piers by big corporations also continues in the municipalities of Orion and Mariveles in Bataan Provinceas part of the reclamation of Manila Bay. Couched under the government’s rehabilitation program, the reclamation will displace over 200,000 families living around the bay. The Philippine Reclamation Authority (PRA) has already identified 38 near-shore reclamation projects which will cover 26,234 hectares or almost the entire near-shore zone of Manila Bay.

Heaviest impact on women

Women in the poorest communities have borne the heaviest impact of worsening poverty and hunger, loss of livelihoods, and in some areas even the loss of shelter. As far as division of house work is concerned, some community organizers said that although there have been equal sharing of tasks among men and women in organized communities, in most households that have not yet been reached by progressive organizing, women are still expected to do majority of the housework.

On top of this, given the deeply entrenched feminization of care, poor women are also heavily affected by the anxieties brought about by the lack of incomes, their hampered ability to put food on their table, and the uncertainty of how long their families will still have to endure this situation. In some urban poor communities, the formidable expectation on women to fulfill their “primary” responsibility as caregivers even in impossible situations have pushed some of them to perform sexual activities in exchange for food aid for their families—because the aid distributed by government is simply not enough. In cramped households and communities with shared bathrooms, cases of sexual harassment, rape, and incest rape of women have also been reported.

Pandemic exposes the crisis of neoliberal capitalism

The glaring inability of the state to mitigate the negative socioeconomic impacts of the lockdown—and let alone to lift the national economy from rock bottom—is a consequence of the government’s unswerving adherence to the neoliberal playbook, which hollowed out its capacity to even do the bare-minimum of funding and implementing social welfare programs.

For decades, the goals of the government have always been to champion the hegemony of the market in economic activities and further open the national economy to more foreign trade and investment. In pursuit of these, the state hasundermined its mandate to protect human rights in the interest of creating policies that favored a cheap-wage economy, agricultural liberalization, trade and investment liberalization,plunder of natural resources for profit, privatization of public utilities, and commercialization of social services.While facilitating corporate takeover of the national economy, the government has also prioritized drastic debt-servicing measures. These have spelled higher taxes for the people and massive cuts in public investments going intosocial services and the productive sectors of the economy, which have already been left in the hands of big businesses.

The result is an economy with a weak foundation, characterized by: (1) withering agriculture and manufacturing sectors and the erosion of society’s most productive forces; (2) low-quality and unsustainable jobs, high unemployment, and low incomes for the poor majority; (3) growth in wealth and profits for the richest few families and largest corporations;(4) limited access to social services for the poor; and (5) overreliance on global markets. With nearly all economic activities grounded to a halt because of the pandemic, the systemic consequences of neoliberalism now translate to even greater vulnerabilities for the poor and marginalized.

As the pandemic forces the system to confront the conditions of poverty and inequality it has created, the system finds that it has caused its own demise. Its survival, after all, depends on the very people it has exploited, deprived,and impoverished for decades. With these people now in grave destitution, the state—depleted of its welfare capacity by the neoliberal system—crumbles in the face of the pandemic as it struggles to provide for the survival of millions deeply submerged in poverty.

Yet even as it is confronted by a crisis of unprecedented proportions, the state cannot go beyond its neoliberal imagination.To supposedlyaddress the food shortage due to restricted food production and distribution, the Agriculture Department called on indigenous peoples “to transform part if not most of their idle ancestral lands into vegetable and high-value crop farms.”[2]This appeal now comes after decades of neglecting agrarian reform, local production, and indigenous peoples’ rights over their ancestral domains. Yet the Department remains mum on state- and corporate-perpetrated land grabbing, land use conversions for private interests, and agricultural liberalization—all of which have deteriorated the country’s capacity for food self-sufficiency, thereby increasing its vulnerability to hunger aggravated by emergency situations such as the current pandemic.

Regarding economic recovery, the Finance Department announced that the ADB has lent the Philippines USD1.5 billion, the largest ever budget support to the country, to help with its recovery.[3] The Economic Planning Agency has also hinted that its recovery plan will largely depend on “the participation of the private sector to create jobs” and will also look into the “Build, Build, Build” infrastructure program as the main driver of the economy.[4]

However, the present crisis cannot be solved by the same system that created it. Rather, it demands us to radically reimagine and restructure the way we organize our society and our economy. Increasing state intervention in the economy is not enough, as the stateitself is too riddled with corporate interests. What we need is for progressives from different sectors and peoplesto collectively imagine and struggle for asociety that values individual and collective rights, participatory democracy in all aspects of life, social justice, gender justice, and ecological justice. One important guide towards the realization of this social change are the principles of deglobalization—an ethical perspective and economic paradigm first defined by Walden Bello in 2002—which upholds the primacy of“values over interests, cooperation above competition, and community [one that is based on shared values and transcends differencesin blood, gender, race, class, and culture] above [narrow economicand bureaucratic] efficiency.”With these foundational principles, deglobalization offers an economic paradigm that “strengthens social solidarityby subordinating the operations of the marketto the values of equity, justice, and community andby enlarging the range of democratic decision makingin the economic sphere.”[5]

NOTE: Some of the community-based narratives in this article are based on the results of Focus on the Global South’s rapid assessment of the impacts of the COVID-19 lockdown on partner communities and organizations in the Philippines.

*Bianca Martinez is a Programme Officer with Focus on the Global South and based in Manila, Philippines

[1]https://focusweb.org/philippines-informal-workers-face-brunt-of-covid-19-lockdown/

[2]https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1259755/fwd-da-appeals-to-ips-transform-idle-ancestral-lands-into-food-production-areas-amid-ecq?fbclid=IwAR1CCMcdpK0Vl5f9Hkk-vJhEGbEy3k-47Md9uHwJTHKrukjo76yCk3RWGHU

[3]https://www.rappler.com/business/258895-adb-loan-budget-support-philippines-coronavirus

[4]https://business.inquirer.net/295287/acting-neda-chief-gets-list-of-priorities-from-duterte-national-id-on-top

[5]https://focusweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Revisiting-Reclaiming-Deglobalization-web.pdf

Photo Caption:

Iraynon Bukidnon women prepare relief goods to be distributed in their community. With the inefficient (and in many cases politicized) delivery of government aid, NGOs such as LILAK (Purple Action for Indigenous Women’s Rights) and peoples’ organizations have initiated efforts to extend support and solidarity in their communities. Antique Province, Philippines. 2020 April 16. Photo by Jhona Vicente.