What I’d like to do is focus on some economic vulnerabilities exposed by COVID-19 and how the impact of the virus might, in fact, provide an opportunity to effectively address them. In other words, I would like to focus on how COVID-19 might, despite its terrible effects, enable strategic economic transformations.

The first vulnerability is the disruption of global and regional supply chains. The second is distorted development owing to overspecialization in certain economic activities brought about by globalization. The third is the problem of growth and carbon emissions. COVID-19, it is our contention, tragic as it is, provides an opportunity to reduce these vulnerabilities. As someone said, let’s not let a good crisis go to waste.

Disruption of global supply chains

First of all, on the disruption of global supply chains. Global supply chains have been considered one of the most important innovations of transnational corporations. They refer to the TNC’s organization of production by locating different phases of production in different places throughout the globe according to where they are best located in terms of overall profitability for the TNC. The key considerations are wage levels, tax rates, and transport costs. The creation of global supply chains has been a major cause of deindustrialization in and community disorganization in many countries and regions, such as the United States and Southeast Asia.

This negative impact was well known before COVID-19. What COVID-19 did was to show the vulnerability of global supply chains to disruptions caused by pandemics, disasters, and wars. Thus in January and February, the halt in industrial production in China owing to the lockdown around Wuhan and the drastic curtailment of industrial activity throughout the country resulted a rapid drawdown of supplies of essential commodities in many countries importing a whole range of products from China, including face masks and other personnel protective equipment and essential medical devices such as ventilators and respirators, since these countries had lost the capacity to produce them owing to deindustrialization. At the same time, countries that supplied China with industrial components and raw materials, such as the ASEAN countries, saw their economies suffer owing to the steep drop in Chinese industrial demand for their exports.

We saw the same thing happen with food supply chains. More and more local and regional food systems that used to provide most of domestic production and consumption of food have retreated in the face of the onslaught by modern food supply chains. These supply chains–which are dominated by large processing firms and supermarkets that are capital-intensive, with relatively low labor intensity of operations–constitute roughly 30 percent-50 percent of the food systems in China, Latin America, and Southeast Asia, and 20 percent of the food systems in Africa and South Asia.

COVID-19 severely disrupted these supply chains. For instance, supplies of soybeans from Argentina to the rest of the world were disrupted when communities refused to allow vehicles carrying soybeans to the port of Rosario were stopped by communities which were fearful that they were carriers of the COVID-19 virus. In many parts of the world, local food producers were apparently ready to fill the need caused by supply chain disruptions, but they were handicapped by inappropriate, very restrictive health measures preventing food supplies from the surrounding countryside from entering the cities.

COVID-19 provides an opportunity for countries to relocalize both industrial and agricultural production. This would not only reduce supply disruptions during emergencies. It would revitalize economies by reviving local industries and local agriculture and bring back decent jobs that have been lost to job-displacing and wage-reducing supply chains. Part of this process would mean ending TNC-biased investment policies and ending unequal trade treaties as well as reversing job-destroying commitments to the World Trade Organization.

COVID-19 and distorted development

Let me now move on to the problem of the structural distortion of an economy owing to overspecialization created by globalization, taking the Philippines and Thailand as examples.

Over the last few decades, the Philippines has specialized in training and sending unskilled, semi-skilled, and skilled labor abroad. Over 10 million Filipinos now work abroad, a figure that comes to some 10 percent of the country’s population. Labor export is now the country’s biggest dollar earner, with remittances contributing something of the order of 20 percent of revenue from exports. With COVID-19 cutting down international travel by at least 90 percent and with labor-receiving countries raising their barriers to the entry of workers and migrants, the Philippines has been hit badly. The rough estimate is that 700,000 overseas Filipino workers will lose their jobs by the end of the year, and thousands have been returning home to a country that has already seen a massive rise in domestic unemployment owing to the halt in economic activity caused by COVID-19.

However, there has been one area that has not seen a drop in demand but an increase: health care workers, of which the country has been one of the top producers for the world market. A tragic example of how globalization has distorted the Philippine economy is the contradiction between the massive needs for health care workers in the country owing to COVID-19 and the rush of many health workers to leave to fulfill contracts abroad, where many were likely to be deployed to tend to patients with COVID-19! This has resulted in unfortunate situations where representatives of the government have unfairly accused departing health workers of lack of concern for their fellow citizens when, in fact, it is structural conditions that the government has fostered with its labor-export policy that are largely at fault.

The equivalent of the Philippines’ specialization in labor export in Thailand is the tourist industry which accounts for about 20 percent of the country’s GDP. The number of tourists visiting Thailand increased from 35.3 million in 2017 to 39.8 in 2019. Tourists from China surpassed 10.9 million visitors in 2019, making up close to 30 percent of total tourists. Owing to COVID-19, tourist arrivals have dwindled to nearly zero, resulting in an estimated loss of 10 million jobs. The airline industry has been so foreign tourist-dependent that practically all Thai-owned airlines, including Royal Thai Airways, are close to collapse and can only remain open with government subsidies and soft loans.

COVID-19 has revealed the perils of overdependence on a few industries, labor export in the case of the Philippines and tourism in the case of Thailand. The challenge to the Philippines is to transform its economy to create decent domestic employment opportunities that will reduce the need for people to go abroad. This will involve increasing domestic demand significantly, which can only be done if investment is focused on industries that cater to rising domestic demand rather than foreign demand, thus making local wages more attractive. Domestic demand, in turn, cannot be raised significantly without significantly reducing inequality. Also important will be curbing the country’s continuing high population growth rate through implementation of the Reproductive Rights Act.

Some have said that the challenge to Thailand is to increase domestic tourism. I think this is important, but the real challenge is a bigger one, and that is how to radically reduce the Thai economy’s dependence on tourism. This will mean further diversifying the country’s industrial and service sectors to create more attractive high-value-added jobs to attract those now in the tourism sector. This will mean targeted investment as well as measures to reduce inequality and raise wages in what is now regarded as the world’s most unequal society.

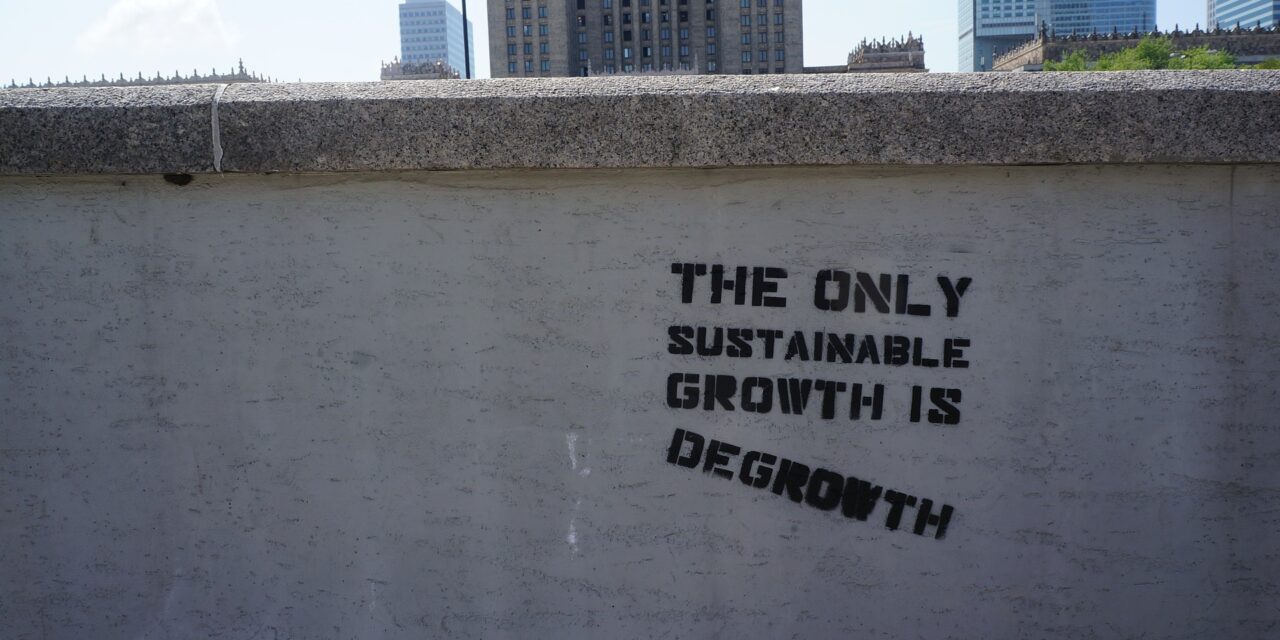

COVID-19 and degrowth

The third challenge I’d like to address is one posed to all economies: how to take advantage of COVID-19 to push economies towards radical reductions in carbon emissions.

During the recession that followed the financial crisis of 2008, carbon emissions dropped significantly. For example, the 2008–2009 Global Financial Crisis saw global CO2 emissions decline by 1.4 percent in 2009. The pattern seems to be replicated during COVID-19: Daily global CO2 emissions decreased by 17 percent by early April 2020 compared with mean 2019 levels, just under half owing to changes in surface transport. At their peak, emissions in individual countries decreased by 26 percent on average.

The task will be how to continue bringing down C02 emissions after COVID-19, so that we don’t return to the global financial crisis pattern of a rise of a decline in C02 emissions in 2009 followed by 5.1 percent increase in emissions in 2010.

The task will fall especially on countries that have either historically or presently been the biggest carbon emitters. One thing seems clear: that decoupling growth from increase in carbon emissions – that is, registering GDP growth while decreasing carbon emissions owing to more “efficient,” less carbon-intensive production processes–does not work. Economies will have to “degrow”, not just reduce their rate of GDP growth.

Since the imperatives of addressing poverty and respecting global justice and equity demand that many countries in the global South will have to experience some growth, then it is clear that the adjustment in terms of radically restraining growth and consumption must, for the most part, on the rich countries–though, of course, in both the rate of growth and consumption the poorer countries must not follow the high-growth model of the West and the Asian economies by putting the emphasis on equity-enhancing strategies. The Green New Deal put forward by progressive legislators in the US is a step forward, but it is still unclear if it completely embraces a degrowth paradigm.

Let me just end by saying that the three challenges I have touched on will necessitate a great deal of political will and cooperation from civil society. I see them being effectively addressed only through democratic processes with a great degree of citizen participation.

Walden Bello, PhD, is currently the International Adjunct Professor of Sociology at the State University of New York at Binghamton and co-chair of the Board of Focus on the Global South, a program of the Chulalongkorn University Social Research Institute. He is a former member of the House of Representatives of the Republic of the Philippines (2009-2015), where he chaired the Committee on Overseas Workers’ Affairs, and a retired professor of the University of the Philippines. He is the author or co-author of 25 books, the most recent of which are Paper Dragons: China and the Next Crash (London: Zed/Bloomsbury, 2019) and Counterrevolution: The Global Rise of the Far Right (Nova Scotia: Fernwood, 2019).