July 25-August 4, 2024

Text and photos by Galileo de Guzman Castillo

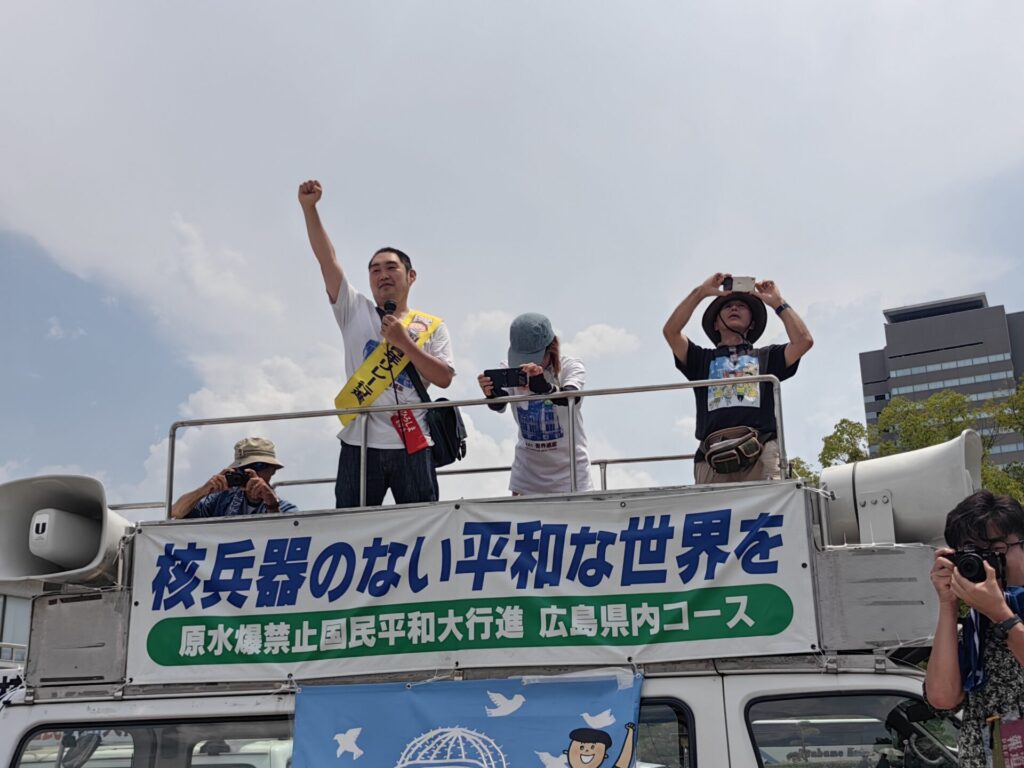

On the eve of the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, peace-loving peoples and movements opposing nuclear weapons and wars have gathered for the 66th year of the National Peace March (Heiwa Koshin) and the 10th edition of the International Youth Relay. Every year, marchers join the Heiwa Koshin from Tokyo to Hiroshima, in different Japanese Prefectures, with various street demonstrations. Carrying the Hibakusha’s (atomic bombing survivors) call for the abolition of nuclear weapons, youth leaders and activists across the world march for just and lasting peace.

Focus on the Global South’s Regional Programme Officer Galileo de Guzman Castillo, together with fellow travelers in various peoples’ struggles walked more than 100,000 steps from Kasaoka, Okayama Prefecture to the city of Hiroshima, where the 2024 World Conference Against A&H Bombs was organized with the theme, “Together with the Hibakusha, let us achieve a nuclear weapon-free, peaceful and just world — for the future of the humankind and our planet.” Five years ago, Galileo also walked the 2019 edition of the Aichi and Gifu Heiwa Koshin.

Alongside this photo essay of the Heiwa Koshin in Kasaoka, Fukuyama, Onomichi, Mihara, Takehara, Higashihiroshima, Hiro, Kure, and Hiroshima; we also share Galileo’s message of peace, justice, and solidarity which was delivered during the various stops of the Peace March, interfaces with local city officials, and interactions with overseas and Japanese delegates in the World Conference; and the International Meeting Declaration.

Local city officials of Kasaoka stand (and walk) in solidarity with the Heiwa Koshin. An important component of the Peace March is the interactions of peace marchers with the local government units, including with the Office of the City Mayor and Council Members, to get their support for the campaign for a nuclear-free and peaceful world. This involves getting their signatures and commitment to demand the Japanese Government to accede to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).

Walking thousands of steps per day for the Heiwa Koshin seems tiring at first but a constant source of renewed energy is when marchers receive motivating cheers and shouts of ganbare / ganbatte! (keep fighting / do your best!), especially from the kodomo (children), as seen in this scene from the march from Kasaoka to Fukuyama. From a very young age, Japanese children are taught omoiyari (sympathy and empathy for others that leads to thoughtful action).

In Fukuyama, a marcher leading the peace calls/chants wears a shirt with the Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution. It states: “Aspiring sincerely to an international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes. In order to accomplish the aim of the preceding paragraph, land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.”

While the Japanese police have their own white helmets and blue uniform, a peace marcher wears a takuhatsugasa, a traditional hat made of rice straw woven together. Everyone needs protection from the glare and heat of the sun as temperatures can often exceed 30°C / 86°F during peak summer months in Japan, which is also the schedule of the Heiwa Koshin. A wise man once said, “The sun may be hot, but the passion, solidarity, and fire within us is hotter.”

A supporter of paw pads new party (a grassroots group of cat lovers in Japan) donning a Free Palestine shirt and bag joins the Peace March in Onomichi. The paw pads new party started 12 years ago as a loose network of cat lovers and concerned citizens who have protested wars, nuclear power, and hate speech—following the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station accident that saw many animals abandoned in affected areas.

Peace marchers beam with smiles and steadfast commitment as they cross the Mihara Bridge, about 70 more kilometers to the Hiroshima Peace Park. One of the marchers, Itsuko Sakatsuko-san celebrated her 77th birthday marching on the streets on July 29. The average age of the hibakusha—atomic bomb survivors—is now 85. Majority of the individuals who are part of the Japanese peace movements are from the older generation.

Rex Alex, International Peace Marcher from the United States of America receives bread specially made by baker and fellow Onomichi peace marcher Sumida-san. In the different stops of the Peace March, one will be treated to an array of delicious and energy-giving snacks such as pastries, candies, fruits, and my newfound favorite wagashi (confection), Yōkan (a block made of red bean paste, agar, and sugar).

Rex Alex and Mie Ohmura-san receives penanto (pennant), an expression of solidarity and support in Takehara. Rex is a student organizer of the Palestine solidarity encampment in Stony Brook University and the State University of New York (SUNY) / Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement. Ohmura-san (“true marcher” who has walked from Tokyo to Hiroshima for 91 days) worked for the Nippon Telegraph and Telephone (NTT) for 47 years and is a longtime member of the Japan Metal Manufacturing, Information and Telecommunication Workers’ Union (JMITU).

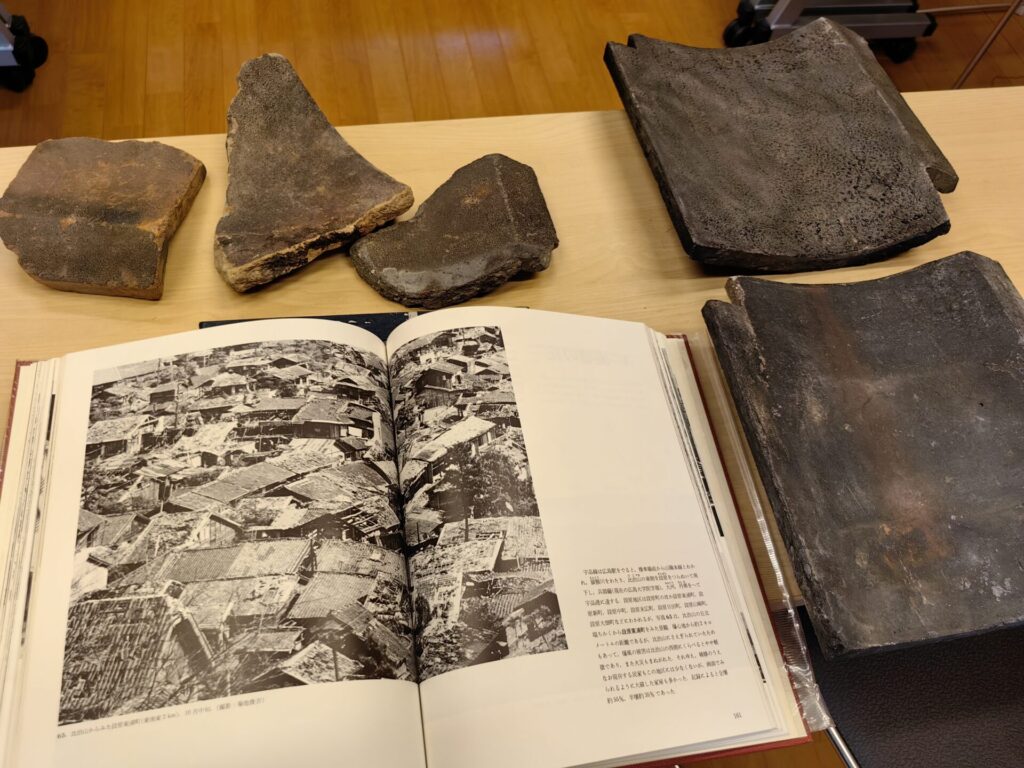

Poignant relics from the aftermath of the atomic bombing include these a-bombed roof tiles collected by Izumi Nakanishi-san from the Motoyasu River in Hiroshima City. He also shows a book documenting the horrors and destruction of World War II, and the suffering caused by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

After a long walk, peace marchers find temporary refuge and breathing space in this wooden pavilion with traditional tatami mats—perfect setting for a sumptuous lunch break. In the various Peace March stops, the International Relay Marchers are afforded the opportunity to get to know their local hosts better and share their experiences both from the Peace March and as activists in their own countries.

The origami crane is a symbol of hope, peace, and healing in Japanese culture. In Higashihiroshima, Ohmura-san receives a gift of senbazuru (one thousand origami cranes) from the kodomo. According to an old Japanese legend, anyone who folded a thousand origami cranes would be granted a wish.

People from all over Japan and the world donate senbazurus to different peace memorials, including this one in Higashihiroshima. The folding of origami cranes and its role in peacebuilding is also connected with the story of Sadako Sasaki, who, at two years old, was exposed to radiation from the atomic bombing of Hiroshima in 1945. “Believing that folding paper cranes would help her recover, she kept folding them to the end, but on October 25, 1955, after an eight-month struggle with the disease, she passed away.”

At Hironakachō, Kure-shi, Hiroshima-ken, the Peace Marchers meet with Miyasako-san (in wheelchair), a 91-year-old hibakusha who was 16 years old when the atomic bomb was dropped in her hometown, Hiroshima. She prepares shiso juice (made from red perilla leaves, seen in the container on the right) for peace marchers every year. Her message: “We have been doing this together since 1987; let’s all continue working together for peace.”

True Marcher Ohmura-san interacts with elementary schoolchildren in Kure and shares with them the purpose of the Heiwa Koshin and why she is walking from Tokyo to Hiroshima. Ohmura-san has three children of her own and her father-in-law is a 2nd generation hibakusha. Her father, a soldier at 21 years old, helped in the cleaning up and cremation of bodies after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

Kure, as a vital port and shipbuilding city, hosts several of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF)’s ports and land facilities, including this Naval Base that harbors many of the JMSDF’s seafaring vessels and submarines. Presently, it is also home to the Kure Pier 6, an Ammunition Depot of the United States Army, Japan (USARJ). One of the calls of the Peace March is to oppose further militarization and militarism.

In the streets of Japan, a usual scene in the Heiwa Koshin is that the Japanese police walk together with the Peace Marchers. They are tasked to provide support throughout the various Heiwa Koshin destinations to ensure the smooth flow of traffic and the safety of the peace marchers, especially when crossing the highways (and even tunnels!)

Yamaguchi-san (sitting, in orange shirt), at 92 years old, is one of the “legendary” Peace Marchers. He joined the Heiwa Koshin 12 years ago and since then, has walked every year, completing 9 out of the 11 currently existing routes/legs of the Peace March. He wears an orizuru gift—paper cranes folded to represent the 103 Articles of the Japanese Constitution—from a blind woman he met in one of the editions of the Peace March.

Peace Marchers from different routes/legs converge at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park on August 4, the day of the opening ceremony of the World Conference Against A&H Bombs. Japanese cultural workers and activists welcome them with solidarity songs of peace, starting with Aoi Sora (Blue Skies).

All in a day’s work for the Heiwa Koshin! After 91 days, the Japan Peace March concludes with messages of solidarity and renewed hope for a more just, sustainable, and peaceful world. While this marks the conclusion of the Peace March, it is just a “temporary ending” as the World Conference Against A&H Bombs commences thereafter.