ANALYSING

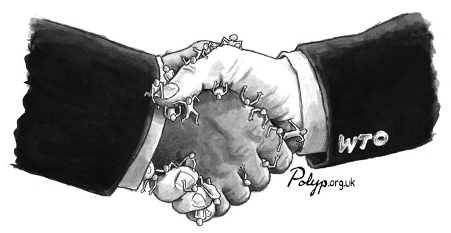

THE 12TH MINISTERIAL CONFERENCE (MC12)

OF THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION (WTO)

Download the PDF: English | French | Spanish

A. BACKGROUND

The World Trade Organisation (WTO) held its 12th Ministerial Conference (MC) in Geneva from 12-17 June 2022. The conference was held in trying and uncertain circumstances, with the pandemic and Ukraine war showing little signs of resolution and a resultant spiral in global fuel and food prices. Global trade had taken a battering due to the pandemic and the WTO was under pressure to deliver an ambitious outcome after a string of lacklustre ministerial meetings in the last decade. The northern countries came well prepared to Geneva; their intention was to stymie a comprehensive waiver of rules on the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), block a permanent solution on public stockholding for food security purposes, sign an agreement curtailing fisheries subsidies under the guise of meeting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and extend the moratorium on duties for e-commerce transactions. On the other hand, developing countries were unfocussed and disunited; they frittered away the opportunity to demand real commitments on Special and Differential Treatment (S&DT), removal of Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs) in technology-transfer for pharmaceuticals and medicines, address their long standing demands on public stock holding, and tackle the global food crisis and current and future pandemics. Unsurprisingly, the rich countries (and the transnational corporations they host) emerged as clear winners from Geneva and a moribund institution was revived.

In this context, La Via Campesina (LVC), the global network of peasant movements, and Focus on the Global South (Focus) organised a critical review of the MC 12 ‘Geneva Package’ on June 27, 2022 with a focus on public health, agriculture and fisheries[1]. The briefing note below examines the MC 12 within a broader political frame and the outcomes are discussed from the perspective of social movements, small-scale producers and working classes worldwide.

There are three annexures, appended to this note, that are responses to the MC 12 outcomes. The first is the Geneva declaration from the delegation of La Via Campesina that was present in Geneva during the WTO MC 12. The statement articulates an alternative vision for agriculture trade that is based on the principles of food sovereignty. The second annexure is the statement from Focus on the Global South on how the WTO continues to fail the Global South. Finally, we carry the inputs made by Professor Walden Bello at the online session organised on June 27, 2022.

B. DECODING THE GENEVA PACKAGE & WTO’S “REVIVAL”

The Ministerial outcomes signify a big victory for the World Trade Organisation (WTO), developed countries and big business. For instance, the text adopted on Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs) reflects the European Union (EU) position on the use of existing flexibilities and the US position to narrow the scope to vaccines. Further, there has been an undermining of developing country positions on agriculture, fisheries, and institutional reforms; and an emphasis on issues of offensive interest to developed countries such as e-commerce, and trade facilitation. Immediately after the MC 12, the Group of 7 (G7) countries issued a declaration reaffirming open trade and markets, focussing on removal of export restrictions rather than addressing food security, which is now a global crisis. The same pattern was repeated on the WTO and pandemic response. On all these fronts the processes are being hijacked by the developed countries as ‘first movers’, that are pushing through the same proposals through various channels.

The biggest win from Geneva is for the WTO itself, in the prospects for the perpetuation of an organisation otherwise seen to be on its last legs. The WTO had not come up with a consensus declaration for a long time. While the MC 09 in 2013 adopted a package that included decisions on some areas, there was no consensus on a key item: the permanent solution on the issue of public stockholding for food security. The last MC 12 in Buenos Aires was a dismal failure with no substantive outcome other than a decision to continue talks on fisheries subsidies and a work programme on electronic commerce. The WTO had appeared as one ministerial away from being rendered defunct and irrelevant. MC 12 is now being touted as a victory in that it can indeed achieve agreement despite an adverse global situation; the conclusion of the ministerial with an ambitious work programme is a reassertion of its preeminent role as the global engine for free trade and liberalisation.

-

- For peasants, small-scale food producers and workers, the MC12 outcome is a big strategic defeat.

The outcomes have merely reaffirmed how the WTO works against the people, in its protection of the interests of transnational corporations (TNCs) and management of ‘free trade’ – which is nothing but a vehicle for developed countries to push their agenda against the interest of the global south. Developed country groupings as the G7 and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) push forth with forceful demands on efficiency and productivity while shutting out demands for self-reliance by the developing world. This chorus for ‘free-market’ is also amplified at the Group of 20 (G20) meetings, and other global arenas such as the World Economic Forum.

Even multilateral organizations such as the World Food Programme (WFP) and the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) are backing the same rhetoric of keeping trade open, rather than emphasising the building of capacities for health, food security.

The WTO as an organisation has nothing left for the countries of the Global South, or for the peasants, indigenous people and the working classes across the world. Rather, it is a cheer-leader for industry elites, whose ambitions are often in conflict with the world’s working class in all continents.

The so-called Doha Development Agenda (DDA) initiated in 2001, which promised to underscore the developmental nature of new multilateral negotiations by addressing issues raised by developing countries, is in tatters. There is hardly any interest, particularly from the rich countries, to pursue this agenda and the failure to achieve consensus on it has in fact been used as the basis to call for reforms in the decision-making processes within the WTO. In the current assessment, there is nothing left for small farmers and producers in the South or North.

In short, the developing world came out of MC 12 without health security, food security and weakening of their collective positions. The peasants, indigenous peoples and the working class in the North, who are already sidelined by excessive industrialisation and corporate control, have nothing to gain from the MC12 outcomes. It is important to highlight here that the small-scale dairy farmers or small-scale meat sellers of Europe, Australia or United States (or for that matter any advanced economies) are not the beneficiaries of the huge subsidies and incentives offered by wealthy northern governments. All these so called outcomes from these Ministerial meetings are only meant to keep the pot-boiling for the multinational agribusinesses headquartered in the Global North. The real losers and victims here are peasants and rural communities everywhere.

In terms of some of the significant sector-specific issues, the developments vis-à-vis the proposed TRIPs waiver, and on agriculture and fisheries, have been shocking. These and other aspects are discussed in some detail below.

-

- Trips waiver: A closer look

On the TRIPS waiver proposal, the outcome did not address the pandemic situation and the serious continuing impact in the South. Low-income countries continue to struggle with vaccine access and the increased burden on their public health systems. The MC12 decision on the TRIPS agreement is not a waiver, even though it may be sold as such. It is only the existing compulsory licensing system repackaged and a restatement of flexibilities. The revised text that was used as the basis for the negotiations reflected the positions of the European Union, Norway, United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Germany, which have consistently opposed the India and South Africa proposal, and is in the interest of Big Pharma: specifically Pfizer, Moderna, Astra Zeneca and Johnson and Johnson.

The outcome falls short of the waiver demand by India and South Africa, which was endorsed by 63 countries and supported by more than 100 countries. The text has a dysfunctional and contradictory element where countries who can produce vaccines are not allowed to do so. In addition, the decision does not cover aspects that are needed to scale up production such as know-how, technology, trade secrets – all of which continue to be protected. Diagnostics and therapeutics, which are easier to produce, are not included under these flexibilities. Countries are to use whatever limited provisions are available, and with many developing countries facing multiple crises where pursuing compulsory licences and financing is difficult. Now, as the World Bank (WB) and International Finance Corporation (IFC) advance into this financing space, the implications of this will also have to be monitored.

It is unlikely that the agreement could be further enhanced, despite a promise to consider extension of the coverage to include production and supply of COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics, given the aversion to the use of Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) waivers in dealing with (future) pandemics. Furthermore, countries such as India also backed off on their stand on the issue. This has adverse implications for developing countries and South-South solidarity.

Two parallel global processes are also relevant here: one for declaring health emergencies and another for a pandemic treaty, but neither look to include IPR waivers to deal with public health emergencies, or other coordinated responses and solidarities from the Global North. Instead, there is a move towards greater codification under the WTO rather than the World Health Organisation (WHO) of measures to respond to global health emergencies gaining precedence.

-

- A dive into the fisheries-related and other outcomes at the MC12

On fisheries, the agreement disregards Special and Differential Treatment (S&DT) as the developed countries blocked such distinctions even after 21 years of concrete proposals by developing countries. The push by the developed world has been towards minimising S&DT both in coverage and duration (now allowed only for two years), even as many countries do not have the capacity to register small scale fisheries under these provisions due to data and management problems. Least Developed Countries (LDCs), developing countries, and developed countries now have the same status where the latter have no applicable disciplines on overfishing, managing to restrict this aspect with the sustainability clause. This is because the fisheries sector in the developed world meets scientific and technical criteria for sustainability. Fisherfolk movements worldwide are also opposing the Elimination of Fisheries subsidies under Illegal, Unreported, Unregulated (IUU) fishing categorisation. In many developing countries boats that belong to the small-scale or artisanal fleets are yet to be registered. The WTO’s sweeping attempt to remove subsidies on the basis of such categorisation pushes the most vulnerable fishworkers into poverty.

What is indeed happening is a reverse S&DT for rich countries, that can continue to subside fishing activities of the multinational corporations hosted in these countries. The fisheries agreement signifies a big loss for the South and for the small-scale fisherfolk in the Global North.

Developing countries will need to rethink their future approach on this critical issue.

There has been no agreement on agriculture at the MC12 and no headway in discussions on the critical aspect of Public Stock Holding (PSH), which was a key demand of the developing countries in the interest of food security. It may be highlighted that agreement on PSH should have been achieved in 2017, as developing countries fought to the end at Buenos Aires. Even in the Global North, in countries like France, and particularly after the supply-crisis in the wake of the pandemic and the wars, the peasant movements have been insisting that public stockholding measures are vital for achieving food sovereignty and reducing external dependencies. Yet, at the MC 12, there is no mention of the issue or of timelines by which there will be a decision to this end. There is no reference to the Special Safeguard Mechanism (SSM) which is critical for developing countries. There was also no discussion at all on the long pending issue of addressing US cotton subsidies.

The larger impasse on European Union (EU) and United States (US) subsidies also continues. The WTO Agreement on Agriculture (AOA) allows high subsidies by developed countries (with transnational corporations in the Global North as the sole beneficiaries) while disallowing developing countries from supporting their small farmers. The EU and the United States (US), which want developing country raw materials (agri and non-agri) continue to block value addition within the developing countries, and the maximum impact of the control of the global food supply chain by four or five mega agri-businesses is on the net food importing countries (NFICs). In the process peasants and small-scale food producers everywhere lose out. It also feared that the decision on World Food Programme (WFP) procurement may mask more rules on export restrictions going forward.

In terms of broader organisational framework and processes which includes the issue of WTO reforms, there has been continued US unilateralism in blocking progress on the functioning of the dispute settlement mechanism and appointment of judges to the Appellate Body. There is growing concern of ‘friends shoring’ in trade with the US propping up countries supporting democracy and free trade – and thus mobilising against China, which it sees as benefitting unduly from the WTO. The issue of reforms (and the word itself) has also been hijacked, to include proposals for further market access and liberalization that are a danger to developing countries.. In the present balance only the LDCs continue to receive concessions. There is in turn a growing centrality of the capacity building and financing central role of International Financial Institutions such as the World Bank, which holds further debt implications.

-

- What were the forces at play that resulted in the MC12 outcomes?

The developments in Geneva in June 2022 are not a-contextual, but a result of years of political pressures which have been fracturing developing country solidarity. This was a skewed process, in which ‘green room’ consultations were used extensively. Developed countries such as the US, Canada, EU and others engaged with select developing countries (India, China, South Africa, Indonesia) leveraging various geopolitical tensions.

Most negotiations were conducted this manner with no time for much of the developing country members to consider or discuss proposals. Documents were closed before many substantive issues could be decided, as in the case of the fisheries agreement, for submission to the ministerial. The conference thus became more of a platform for politics and interplay of geopolitical alliances, rather than content-based discussions. These closed room discussions now appear to be the template and new norm for WTO under the ‘reform’ agenda going forward. These have pushed transparency to the backburner with processes becoming more opaque and exclusive, even under the guise of ‘multilateralism’.

The role of the current Director-General (DG) of the WTO should also be scrutinized. DG Nkozi Okonjo-Iweala was brought in as a compromise candidate and a ‘voice of reason’ in the face of the insistence by then US President Trump on the South Korean candidate.

There is no evidence of her supporting South positions in her earlier role with the World Bank. At MC 12 she is reported to have pressured developing countries to fall in line, instead of protecting the interests of the global South.

While there has been discussion of the dominance of and manipulation by developed countries, developing countries have also shown themselves unable or unwilling to protect the interests of their peoples, and certainly not ready to take on the failure of the WTO on their hands. The shift in India’s position in which it reneged on its stand on TRIPs and on agriculture is an echo of the 1988 Uruguay Round. It is more disappointing that the outcome is being positioned as a victory rather than because of pressure on different fronts. The South African government is also seen as increasingly neoliberal. Even in the face of progressive proposals on the TRIPs waiver in Geneva, its Trade Ministry was not willing to walk out on the agreement, which is now framed as a ‘success story’ and victory for local manufacturing.

Despite different groupings coming together in a joint proposal on PSH, the Group of 33 (G33) and the African Group were given no voice in the negotiations in which the US and Brazil had ‘gone rogue’. Many of the developing countries were concerned and knew this to be a moment to try to change the WTO rules to work for them. However, the amplification of ‘false solutions’, and very aggressive media campaigns made it hard for them to criticize the outcome.

C. IMPLICATIONS FOR ORGANISING AND CAMPAIGNING ON THE WTO

From a Global South perspective, it is important to stymie the functioning of the WTO which is a prop for neoliberalism and neo-imperialism. Its continuity is only a carte blanche for the exploitation of the developing world and the already marginalised peasants and working class of the Global North. In the past 27 years, the WTO has lost its legitimacy as a multilateral institution and the way forward for the developing countries to reject it completely. In the light of the MC 12 outcome, developing countries should also reassess the role of the current DG and call for her resignation.

It is also important to emphasise here that WTO (and other regional and bilateral agreements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, the Indo-Pacific Economic framework and countless other such instruments) are mechanisms to sustain and grow transnational corporations, under the garb of globalization. Here, we recall the legendary peasant leader – late Mr. M.D Nanjundaswamy from India – who once said, “The word globalization, if you want the meaning of it from me, I would say it is a kind of recolonisation of the South by the Northern Corporations. But it doesn’t stop there. It is a kind of colonisation of their own people in their own countries also. So its colonisation internally and colonisation internationally, by the same few multinational corporations. And that is globalization”.

The WTO facilitates this re-colonisation of the working class. It continues to represent the interests of multinational corporations, while disregarding and disrespecting the lived realities of peasants, indigenous peoples and the working class everywhere.

On the specific issues, it is essential to review and re-organise positions focussing on the unjust frameworks supporting agreements on agriculture (under which developed countries use subsidies to support agri-businesses) and fisheries. It is also crucial to strengthen global food sovereignty movements and national struggles against the WTO, particularly with reference to the issue of public stockholding to address the food crisis.

It is imperative for civil society to step in and provide regular and relevant analysis on what has happened in Geneva and beyond and organise against the ill-effects of the ministerial outcome. Global movements have played a significant role in the past, which we must build on for future struggles in support of the rights of peasants, indigenous peoples and working classes. It is necessary to strengthen such alliances going forward.

—

[1] Speakers at the event included Professor Walden Bello (Focus on the Global South), Ranja Sengupta (Third World Network), Zainal Arifin Fuad & Jeongyeol Kim (La Via Campesina), Professor Biswajit Dhar (Jawaharlal Nehru University) and Lauren Paremoer (People’s Health Movement).

- ANNEX I: Geneva Declaration: End WTO! Build International Trade based on Peasants’ Rights and Food Sovereignty!

- ANNEX II: Big Pharma and Big Tech Win at the WTO — #MC12 Fails the Global South

- ANNEX III: Intervention of Walden Bello at a Meeting on the Results of MC 12 of the World Trade Organization

![[IN PHOTOS] In Defense of Human Rights and Dignity Movement (iDEFEND) Mobilization on the fourth State of the Nation Address (SONA) of Ferdinand Marcos, Jr.](https://focusweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/1-150x150.jpg)