by Smriti Kak Ramachandran from the Hindu

As the world observed World Water Day last week, Bolivian water activist Pablo Solon narrates how his countrymen forced the repeal of a water privatisation attempt by the government.

What began as an ordinary citizen’s protest against water privatisation laid out the path for a bigger revolution that eventually paved way for Bolivia’s first indigenously elected government.

With worldwide discussions for sustainable management of fresh water resources gaining ground in a bid to ensure water security in the face of depleting water tables and drying up natural water bodies, the debate on people’s fundamental right to free access of water is also a much-debated issue these days, especially with many countries contemplating privatisation of this life-supporting resource.

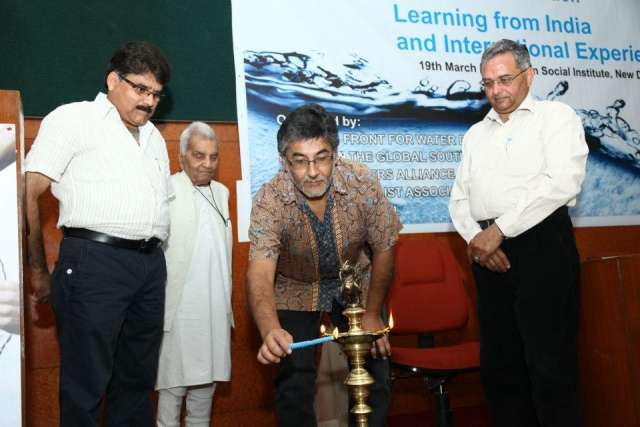

“From a country where everything was privatised and the government was controlled by an outside force, Bolivia has now transformed into a state that controls its resources, manages its moneyand works for its people,” said Pablo Solon, a water activist and former Bolivian Ambassador to the United Nations who is currently in India to share experiences of how an aborted water privatisation model ushered in changes in this South American country.

Talking to The Hindu, Mr. Solon said even though the struggle to prevent privatisation of water began in 1998 in Cochabamba and in 1997 in La Paz, it took more than seven years of countless protests, at least three deaths and scores of injured men and women, to overthrow the private companies that were given the charge of supplying water in the city.

“The private companies had only one motive to make profit. They made no investment; they used the state’s infrastructure and yet expected to make only profit. In Cochabamba, the first thing that they did was to increase the tariff by 300 per cent. The citizens came out on the streets,” he recalled.

In Bolivia, where water is considered the ‘blood of mother earth’, privatisation of water angered the common man. “Gas, energy, railway — everything had already been privatised, but with private companies being offered the water sector as well, people became angry, they joined forces, they came out together and there was a time when people began to seek reclaiming of what they considered their resources,” said Mr. Solon.

The policy followed by the private companies to offer premium services to those who could pay, alienated the poor. “The reaction to that policy was that people asserted their right of equality to quality water and infrastructure. The private companies were not even taking care of the infrastructure and the resources like dams and treatment plants that they inherited. Yet, in La Paz, the private company made three million dollars in a year; money which should have been invested for the development of the people was being given away,” he said.

What gave a fillip to the people’s movement was an alliance of the citizens of Cochabamba called La Coordinadora de Defensa del Agua y de la Vida (The Coalition in Defence of Water and Life) that was formed in January 2000, he pointed out. “People just came out on to the streets, the alliance shut down the city, no one was allowed to enter or exit, a few people were killed and though the government initially tried to repress the movement, it was forced to step back and agreed to terminate the contracts with the private companies,” said Mr. Solon, who has served as Ambassador for issues concerning Integration and Trade and Secretary of the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR); he also led the resolutions on the Human Right to Water, International Mother Earth Day, Harmony with Nature, and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The influence of the people’s movement in revoking privatisation of water became the bedrock for a nationalist movement, where Bolivians came out to choose their own government. “For the first time, the indigenous people realised their strength and came out to vote, they decided to form their own political instrument. In 2005, for the first time 54 per cent of votes were polled as compared to the usual less than 30 per cent.

“We elected our first President who was not controlled by any outside nation. We made changes to our constitution that makes it impossible for privatisation of our natural resources. Now everything is nationalised and all the money that was being given to transnational corporations is now being used for our own health,education and welfare,” Mr. Solon said.

Urging India to learn from the Bolivian experience and refrain from moving ahead with private public partnership models in the water sector, he said: “It is our money [collected through taxes] that the private companies use; they make little or no investments, why should the government not retain the control over natural resources then? Besides it is better to say not to allow privatisation now rather than let people wage war later.”