Soren Ambrose*

Once upon a time,

the International Monetary Fund (IMF) seemed immune to criticism,

regardless of the damage its neo- liberal policy impositions

inflicted around the globe. That immunity was finally torn away by

the East Asian financial crisis of 1997-98, when criticism of the

IMF's interventions came from all sides. A famous photograph of

long-time IMF Managing Director Michel Camdessus standing,

cross-armed, over Indonesian President Suharto as he signed the

papers for an IMF "bail-out" summed up the neo-colonial

"overlord" role that the IMF's critics had long charged it

with.

The Argentine crisis of 2001-02, where the IMF's

culpability in creating the crisis was generally acknowledged,

probably put the recuperation of the institution's reputation

permanently out of reach.

But the IMF continued to lurch along,

on "automatic pilot," under the unimaginative leadership of Horst

K?hler and Rodrigo Rato, Camdessus's successors. But since

2005, the IMF has suffered a rapid succession of blows, and seems

less like the haughty overlord of 1998 than a boxer staggering around

the ring trying to evade the knock-out punch. Presented here is a

timeline of some of the events of this turbulent period, starting in

June 2005 and running through March 2007.

1. JUNE 2005: THE

MDRI

After a decade of pushing by Jubilee campaigners and over a

year of wrangling among G7 leaders, the G7 finance ministers, meeting

in June 2005, announce that their countries would advocate – and,

given their domination of the voting structure at the IMF and World

Bank, secure – 100% cancellation of the debts claimed by the IMF

and World Bank of countries which completed the Heavily Indebted Poor

Countries (HIPC) debt initiative. That means 20 countries for

the IMF, a figure which has now increased to 24 as others have

graduated from HIPC.

This program, given the prosaic name of

Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI), is still quite limited,

in that it applies to a small subset of the countries requiring such

cancellation: those which had submitted to at least six full years of

the IMF's destructive "sound policies." But it nonetheless sets

an important precedent – the elimination of virtually all

obligations to the IMF and World Bank. For the first time, countries

which have been under the policy domination of these institutions for

as much as 25 years could, potentially, opt out of any further

involvement with them.

The IMF still gets its money –

indeed, the MDRI enables it to collect on some of its most dubious

claims, in full, through the mechanism of trust funds set up by

wealthier countries and the World Bank. But after 25 years of

keeping almost 100 countries on a debt treadmill – structural

adjustment loans leading to more poverty and debt, leading to more

structural adjustment loans – the IMF has lost its leverage to

maintain that cycle with some of the most vulnerable ones.

Unfortunately, but perhaps predictably, given the infiltration of

finance ministries with former IMF and World Bank employees, few

countries avail themselves of this opportunity. Most already have

signed onto new, restrictive programs with the IMF and/or World Bank

by the time the MDRI is finalized. (see #3)

Simultaneously

with the MDRI, the IMF introduces a new program, formulated in tandem

with the debt-cancellation talks. Called the Policy Support

Instrument (PSI), it is designed to offer IMF oversight and "advice"

for countries that no longer need or want IMF loans. In other words,

a country that wants to declare itself free from the IMF – a

"graduation" the IMF could not overtly be seen as discouraging –

can still be pressured to submit itself to IMF rules. Although the

first PSI goes to a non-MDRI country, Nigeria, the PSI is clearly

designed for the new frontier the IMF faces: countries that can

declare their independence of IMF lending. Thus far only four

countries have signed up for the PSI – Nigeria, Cape Verde, Uganda,

and Tanzania, with only the latter two having benefited from the

MDRI. But Ghana is likely to go the PSI route, and several other

countries are considering it.

2. SEPTEMBER 2005: US ATTACKS

IMF

In a widely-discussed speech at the Institute for

International Economics in Washington, at the beginning of the

weekend of the IMF/WB annual meetings, US Under Secretary of the

Treasury for International Affairs Tim Adams, with IMF Managing

Director Rodrigo Rato in the audience, delivers a stinging critique

of the IMF. The speech attracts extra attention because the IMF is

usually seen as deeply influenced by US Treasury. Press articles

focus on Adams's declaration that the IMF is "perceived as being

asleep at the wheel on its most fundamental responsibility, exchange

rate surveillance," a thinly-veiled attempt to shift discontent

among US politicians with China's exchange rates from Treasury to

the IMF. But the speech also lays out in unusually clear terms

the need for re-balancing voting power on the IMF board – where the

status quo threatens the Fund's legitimacy — including a call for

consolidating the eight European seats into one. More importantly,

Adams zeroes in on the IMF's record in impoverished countries,

finding that "the IMF is not a development institution, and it is

clear that the IMF's financial involvement in low-income countries

has gone terribly awry." He calls for IDA, the World Bank's

facility for low-income country loans, to take on most of the work

currently being done by the IMF's Poverty Reduction and Growth

Facility (PRGF), and for the IMF to return to its original mandate of

making short-term loans to facilitate balance-of-payments

corrections.

Adams's speech in effect declares open season

on the IMF, with officials of other governments and independent

commentators taking up the theme that the IMF has lost its way, and

is in danger of becoming irrelevant.

3. DECEMBER, 2005: FAILED

ATTEMPT TO UNDERMINE THE MDRI

The MDRI announced by the G7

finance ministers in June required ratification at the board level of

both the World Bank and the IMF. IMF staff prepare

recommendations for its implementation. Those suggestions and the

discussion that ensued demonstrate just how threatening both the

staff and some members of the IMF board find the MDRI. Using

elaborate inferences, IMF staff construe the rather straightforward

declarations of the G7 to mean that it should devise a new set of

performance criteria before countries are awarded cancellation. Using

very imprecise gauges, the staff concludes that six of the initial 18

countries — – fully one-third — should have their benefits

delayed. Coincidentally, or quite possibly not, four of the five

countries which would not have an IMF program in force after getting

MDRI benefits fall on the list of six. (The other, Uganda, had

recently committed to become the second PSI client.) The IMF, it

seems, is willing to create new rules in order to preserve its

leverage.

The staff proposal receives support from

board members representing the non-G7 European countries, who are

apparently miffed at having the MDRI imposed on them. Some of those

board members went further than the staff recommendations, making

suggestions such as making the cancellation revocable at any time a

country deviated from IMF-approved policy behavior. Rapid

mobilization by civil society organizations, together with the

obstinacy of the US and UK, preserve the MDRI in its original form,

except for a delay for Mauritania (which turned out to be for six

months). The intensity of the board battle makes clear that this is a

significant defeat for the IMF – probably the most significant

rejection of established practice and the staff and management's

policy priorities in its history.

4. DECEMBER 13, 2005: BRAZIL

TO PAY OFF ALL IMF CLAIMS

After successfully concluding, and not

renewing, its IMF program in March 2005, the Brazilian government

makes the unanticipated announcement that it will pay the remaining

$15.5 billion claimed of it by the IMF before the end of 2005.

Civil society activists protest that the move amounts to depriving

Brazil of much-needed funds for social programs in order to pay what

should be considered illegitimate debt claims. But it does have the

effect of eliminating the IMF's leverage over Brazil.

Brazil

is not the first country to make a pre-emptive and complete payoff –

Thailand did so by paying $12 billion in August, 2003. But

Brazil's move sets off a chain reaction of other middle-income

countries taking the same step. This, together with the growing

recognition that East Asian countries are amassing unprecedented

currency reserves in order to guard against future vulnerability to

the IMF, intensifies the perception (and the reality) that the IMF is

facing a crisis of confidence, a crisis of identity, and a crisis of

finance.

5. DECEMBER 15, 2005: ARGENTINA TO PAY OFF ALL IMF

CLAIMS

Just as surprising as Brazil's announcement is

Argentina's two days later that it will pay the $9.8 billion the

IMF claims from it. Although civil society protested, as in Brazil,

there was widespread approval of the resulting independence from the

IMF. President Nestor Kirchner's administration had the most

contentious relationship with the IMF of any government, and in

announcing the pay-off, he reiterates his charge that the IMF is

responsible for the catastrophic collapse of the country's economy

in 2001 – a belief widely shared in Argentina and around Latin

America. While Kirchner's move adds to its crises of relevance and

legitimacy, and now solvency, there is also some relief felt at the

IMF since some had feared that the Argentina would choose to default

rather than repay its arrears.

6. FEBRUARY 2006: DEBATING THE

IMF'S FUTURE

The debate ignited by Tim Adams's speech in

September reaches new peaks, as a number of other top officials join

in the IMF-bashing. Mervyn King, the UK's central bank governor,

uses particularly strong language, warning the IMF risks "slipping

into obscurity." Adams again weighs in again on the exchange-rate

surveillance. Officials of the Canadian central bank jump into the

fray, as does South African central bank governor Tito Mboweni, who

slams the marginalization of African countries on the IMF board. Even

among the G7 officials, the diagnoses are not identical: King, for

instance, locates the IMF's problems in its "micro-managing"

board, a theme not picked up by others. Another critic suggests

merging the IMF and the OECD; others suggest merging it with the

World Bank. The most common suggestion is re-focusing the IMF from

lending operations in low- and middle- income countries to global

surveillance, with emphasis on the imbalances among the largest

economies. Pressure from the establishment for real change at

the IMF has probably never been greater.

7. MARCH 2006:

BOLIVIA TURNS ITS BACK ON THE IMF

Bolivia, under its new

President, Evo Morales, becomes the first country benefiting from the

MDRI to conclude its IMF arrangement and announce that it will not

enter into any new agreements with the institution.

8. APRIL

2006: A NEW ROLE FOR THE IMF?

At the semi-annual meetings of the

IMF and World Bank, the IMF releases official figures forecasting its

first loss in decades in 2007. Much discussion focuses on the reform

of voting power on the IMF board, with the G24 and other

developing-country blocs expressing dissatisfaction with the limited

proposal tabled by Rato, which would give four countries (Mexico,

Turkey, South Korea, and China) immediate quota increases, and

inaugurate a process to consider how to realign all the institution's

votes. New committees are created to explore the financial challenges

facing the IMF and the voting-rights debate.

But the proposal

winning the most attention is Rato's rather unexceptional one to

shift the IMF to a more active role in convening bilateral and

multilateral meetings among major economies to address serious

imbalances (meaning, in particular, China with its controversial

exchange rate and trade surplus, and the US with its massive

deficit). This "new mandate" to mediate global economic frictions

is greeted in extravagant terms by some of those who had been most

vocal with their criticisms. Tim Adams is very satisfied, and Mervyn

King is reported to be nearly ecstatic. But at the end of most

commentaries reporting on this development is the cautionary note: we

shall see if the big players really allow the IMF to play a mediating

role, and if the IMF will have the clout and imagination to pull it

off. Prescient concerns, since by the institutions' annual

meetings in September, this new mandate that was to revive the IMF is

hardly spoken of.

9. MAY 17, 2006: SERBIA PAYS OFF IMF

The

Serbian government announces that it will pay back $500 million lent

by the IMF, thus closing out all obligations to the institution (the

final payment is made in March 2007).

10. MAY 23, 2006:

INDONESIA ANNOUNCES PLAN TO PAY OFF IMF EARLY

The Indonesian

government announces that it will pay off all remaining IMF claims,

totaling $7.8 billion, within two years. That amount is the residue

of some $25 million the IMF lent Indonesia during the East Asian

financial crisis.

11. JUNE / JULY / AUGUST 2006: IMF

INSOLVENCY?

As the committee formed in April to consider

alternative funding mechanisms for an IMF that can no longer depend

on loan-repayment income goes about its work, reports emerge of the

depth of the shortfall, including a possible one-year loss of $100

million in 2007. For the first time, reductions in IMF staffing are

discussed. The idea of selling or revaluing some of the IMF's

massive gold stocks is broached – a move that was rejected as a

financing mechanism for debt cancellation in 2005. The US, whose

Congress must approve any change in the status of the Fund's gold,

signals that it will not support such action.

12. SEPTEMBER

2006: IMF & WORLD BANK MEET IN REPRESSIVE SINGAPORE

The IMF

and World Bank hold their 2006 annual meetings in Singapore despite

warnings that its history of suppressing civil liberties may impede

free discussion with civil society. And indeed, the Singapore

government bans dozens – probably over one hundred – individuals

from entering the country, including some 27 whom the institutions

had approved as civil society delegates to the official meetings. The

institutions issue statements distancing themselves from Singapore's

actions, and requesting that all delegates be allowed to attend. But

most press attention and commentary at the meetings is devoted to the

image of the IMF and World Bank taking cover in another repressive

country to hold their meetings (the 2003 meetings – the last time

they were held outside Washington – were in Dubai, UAE). The

release of a World Bank report on "doing business" that finds

Singapore is the top country in which to "do business" does not

help persuade anyone that the institutions are on the side of human

and civil rights.

13. AUGUST 2006: AFRICAN DIRECTORS PROTEST

IMF QUOTA REFORM PLAN

In a very unusual move, the three Executive

Directors representing African countries send a memo to a meeting of

African Finance Ministers in Maputo, Mozambique, informing them that

the quota reform proposal to be discussed at the annual meetings may

well result in Africa, already quite marginalized at the board,

actually seeing its voice reduced. The EDs signal that they will vote

against the proposal in its current form – again, very unusual –

and recommend that African countries oppose it at the annual meetings

if it has not been changed.

14. SEPTEMBER 2006: IMF QUOTA

REFORM TALKS CAUSE DISSENSION

The substantive discussion that gets

the most attention at the annual meetings is the proposal for changes

to the IMF board's voting structure. The proposal – largely

unchanged from April despite much discussion (see #8), is denounced

by a number of middle-income country governments who believe that the

promised "second step" of the reform will take much longer than

the promised year, and may never be completed. In an unusual step, a

formal vote is taken at the annual meetings, stretching over two

days. Over 20 countries oppose the resolution, including India,

Brazil, and Argentina, but their combined votes fall short of the 15%

of total votes required to prevent the resolution from passing.

(Unfortunately, African governments are mollified by promises that

the process will receive high-level attention, and most support the

proposal.) But the level of dissension at this level at the IMF is

rare, and reports indicate that the discussions (which are behind

closed doors) featured several governments, primarily Asian,

complaining that the proposal failed to outline any shift in the

IMF's role.

15. OCTOBER / NOVEMBER 2006: ECUADOR RESISTS IMF

PRESSURES

As it becomes clear that Rafael Correa might win the

November presidential elections (he does), concerns mount about his

outspoken opposition to IMF policies and interventions during his

brief stint as Finance Minister (a position he was forced to resign

due to World Bank pressure). On the campaign trail, Correa explicitly

threatens to repudiate Ecuador's external debts. But even before

the elections, in October, the Ecuadoran government publicly

denounces IMF pressure to stockpile foreign currency to pay off any

judgment against it in a case involving Occidental Petroleum, a US

company. After winning the presidential election, Correa refuses to

indicate whether Ecuador will make payments on its external debt. (As

of this writing, it appears that Ecuador is making payments, albeit

late ones, and perhaps not full ones.)

16. NOVEMBER 8, 2006:

URUGUAY TO REPAY IMF DEBT

The Uruguayan government announces it

will pay in full the IMF's claims on it, amounting to a little over

$1 billion, becoming the third country in the Mercosur bloc to escape

IMF influence.

17. DECEMBER 2006: NEW ROLE FOR IMF? NO

THANKS!

Commentators report that the IMF has had to downgrade the

talks it was trying to host among five major economic players (China,

the US, the "eurozone", Saudi Arabia, and Japan). The

participants were reportedly failing to sufficiently engage in the

discussions. So much for the big plans announced for a new IMF

mandate in April.

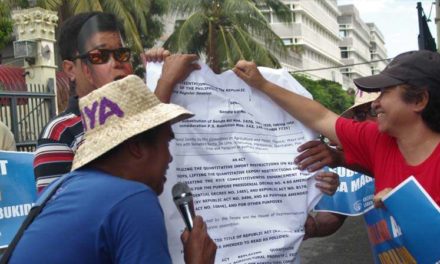

18. DECEMBER 28, 2006: PHILIPPINES TO PAY

OFF IMF AND EXIT ITS PROGRAMS

The Philippine government announces

that after paying the final $220 million the IMF claims of it, it

will not renew its IMF programs.

19. JANUARY 2007: IMF

PRESSURE ON UGANDA POVERTY PROGRAM EXPOSED

In a review under its

PSI program, the Ugandan government is told by the IMF that its

"Bonna Bagagawale" program – under which banks are encouraged

to make below-market-rate loans to small farmers – constitutes

"directed lending" and should be curtailed or re-designed. The

IMF's assertion of recent years that it is making reducing poverty

its top priority is called into question by this determination. And

any hopes that under the PSI the IMF would end its practice of

erecting obstacles to "pro-poor growth" are laid to rest.

20.

FEBRUARY 2007: MALAN REPORT CALLS FOR IMF TO STOP LENDING TO

LOW-INCOME COUNTRIES

A committee chaired by former Brazilian

Finance Minister Pedro Malan publishes its report on how the IMF and

World Bank can collaborate better. One of its highest-profile

suggestions is that the IMF, which it asserts is not equipped to

operate as a development institution, should stop making loans to

low-income countries, leaving that responsibility to the Bank.

The report also notes that the issue of "fiscal space" – the

IMF's insistence that low inflation targets must be maintained even

as they limit growth – has caused increasing friction between it

and the World Bank. Civil society groups have been targeting this

issue aggressively in the last two years, blaming IMF wage caps and

inflation targets for squelching health and education programs.

Unfortunately, the report endorses the continuing use of

"assessments" of low-income country economies by the IMF, and

explicitly supports the PSI.

21. MARCH 1, 2007: ARGENTINA

REFUSES TO RE-ENGAGE WITH IMF

Argentine President Nestor Kirchner

says that while Argentina intends to negotiate with and pays its debt

to the Paris Club of bilateral creditors, under no circumstances will

it enter into a new agreement with the IMF. Having an IMF

program is a pre-requisite for any debt reduction or rescheduling

from the Paris Club. The Paris Club has yet to signal whether it will

make an exception for Argentina.

22. MARCH 6, 2007: RUMORS

THAT TURKEY WILL PAY OFF IMF

The Turkish Daily News, citing

reports in business daily Referans, reports that the Turkish

government is considering paying off its entire $8.5 billion IMF debt

before November elections. If this happens, the big four IMF debtors

as of November 2005 will all have paid their debts early and set the

stage to free themselves from IMF oversight.

23. MARCH 2007:

CHAVEZ STEPS UP CAMPAIGN AGAINST IMF IN LATIN AMERICA

As US

President George W. Bush prepares to embark on a high-profile tour of

Latin America, Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez publicizes his

efforts to eliminate IMF influence in the region. Together with

Argentine President Kirchner, he announces that the new "Bank of

the South" will soon begin operations, allowing countries with

financial difficulties an alternative source of finance.

24.

MARCH 2007: INTERNAL REPORT FAULTS IMF PRACTICE IN AFRICA

A report

published by the IMF's own internal watchdog, the Independent

Evaluation Office (IEO) says that the IMF has failed to communicate

its policies accurately in Africa (saying it has "done little to

address poverty reduction and income distributional issues, despite

institutional rhetoric to the contrary"), has failed to keep

promises (e.g. of increased consultation with civil society), and has

resisted working to expand financing and aid possibilities for

African countries. In commenting on the "fiscal space" issue (see

#20), the IMF agency says that the Fund has "blocked the use of

available aid to SSA [sub-Saharan Africa] through overly conservative

macroeconomic programs."

25. MARCH 2007: ANGOLA

CANCELS CONSULTATIONS WITH IMF

The Angolan government confirms

reports that in February it canceled planned consultations with the

IMF. Finance Minister Jos? Pedro de Morais, himself a former

IMF Executive Director, says an IMF program "will not help Angola

to preserve the economic and social stability it has gained so far,"

and that the country wants to continue implementing its successful

macroeconomic program "without being subjected to restrictive

conditions." There are significant concerns that the Angolan

government may want to prevent investigations of high-level

corruption, and that the maneuver is only possible because of

Angola's enormous oil wealth and the generous aid those resources

have attracted from China. But Angola's announcement remains an

important precedent – very likely the first time an African

government has been in a position to refuse IMF engagement

altogether.

26. MARCH 28, 2007: IMF'S NEW ROLE A FLOP, JAPAN

CONFIRMS

Discussing the upcoming semi-annual meetings of the IMF,

Japanese officials say that no news can be expected from the IMF's

convening of economic powers to discuss global imbalances. Reuters

reports that "there has been scant evidence of progress in the

International Monetary Fund's multilateral consultation process on

global imbalances and Tokyo expects no big surprises at the

international meetings in mid-April in Washington."

*

Soren Ambrose is coordinator of the Africa Solidarity Network a

project of the Daughters of Mumbi Global Resource Centre, based in

Nairobi, Kenya. [email protected]