By Alina Carrillo and Shalmali Guttal

It was Sunday morning on the 10th of July in the Caltex coffee shop in Phnom Penh, a place where many locals went to start their day. In a few moments a crowd would rush in with utter disbelief and heavy hearts. What they would find has shocked both Cambodians and the international community. Mr. Kem Ley, a well-known social and political analyst, had been shot at point blank range, and his body lay beside the coffee he had just been drinking.

This brazen act is the latest in a history of violence in Cambodia that spans more than two decades, motivated by political and economic interests and personal vendettas. In 1997, at least 16 people were killed and over 125 injured when grenades were thrown into a peaceful political rally outside the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh. In 1999, renowned dancer Piseth Pilika was shot while shopping with her niece in a local market. A few months later, 16 year old Tat Marina was beaten and assaulted with nitric acid as she was eating her breakfast. In 2003 Om Radsady, senior advisor to FUNCINPEC, was gunned down after leaving a restaurant in downtown Phnom Penh. The following year, prominent union leader Chea Vichea was shot while buying a newspaper in a busy Phnom Penh street. In 2012, environmental activist Chut Wutty was shot in a forest in Koh Kong province. In 2014, freelance journalist Taing Try was shot in Kratie while investigating illegal logging. The list of victims is much longer and in most cases, justice has yet to be seen.1 Perpetrators have had close connections with the military and other state security agencies; while some of them may have been prosecuted and put in jail, those who ordered the hits remain above the law.

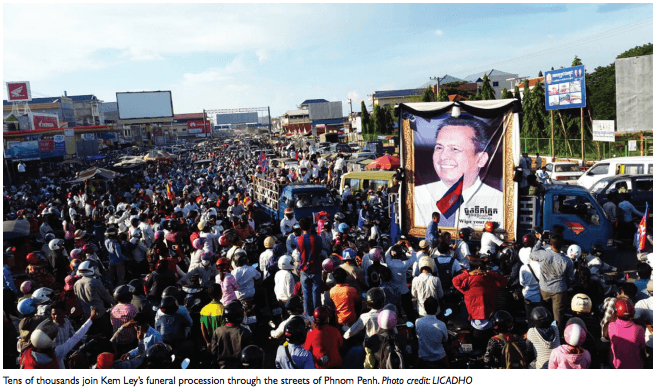

Cambodia’s ruling party has been in power for more than three decades and has built a formidable oligarchy that quiets any opposition through a combination of judicial and extra-judicial actions. Across the country, rural and urban people face arbitrary arrests and detention, brutal forced evictions and threats of violence when they stand up against land grabbing, forest destruction, dams and mining projects. Kem Ley was documenting and speaking out against the abuse of power and judicial manipulation by Cambodia’s ruling elites. Hundreds of people, including friends and family, surrounded Kem Ley immediately after his murder, keeping the authorities at bay and demonstrating a deep mistrust in the ability and integrity of the police and court system.

The absence of accountability in violence surrounding struggles over resources has become appallingly common across Asia. On July 1st 2016, anti-coal mining activist Gloria Capitan was shot dead by two unidentified men in the Philippines. The Bataan province in which she worked has seen environmental destruction and increased health problems arising from the operations of the coal companies, calling into question the beneficiaries of development.

The Philippines has long been a dangerous place for environmental activists, labour organisers, indigenous peoples and other rural peoples defending their lands, territories, livelihoods and rights. According to a Global Witness report, 67 activists were killed between 2002 and 2013, and 22 indigenous activists from the Lumad community were killed in 2015 for defending their communities and land from mining and agribusiness companies.2 Extra-judicial killings and other violence often remain un-investigated and receive veiled or even overt support from state powers. Not even two months into his term, Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte has given the green light to police and vigilante death squads to kill suspected drug dealers. To date, almost 300 people have been killed with scant evidence of their involvement with the drug trade.

In Kashmir, India, young people have taken to the streets as a last resort to dealing with several decades of violent occupation and repression by the police and military with little accountability. In 2010, 120 people, including teenagers were killed outright and not one member of the armed forces was charged or convicted. The recent killing of Burhan Wani on July 8th 2016 has led to further protests and clashes with security forces. Many civilians and security personnel have been injured and killed since Wani’s death. The resurgence of violence and unrest in Kashmir over the last several years illustrates the complete breakdown of trust that impunity cultivates.

In Thailand, streets are kept clear by laws such as The Public Assembly Act B.E. 2558 designed to criminalize protests against the Military Junta and continuing extraction of natural wealth by state and private capital. Those who criticize the state or are deemed “persons of influence” by the regime are taken in for questioning and “attitude adjustment,” or arrested and incarcerated without due process. Regardless of the government in power, violations of peoples’ rights, political persecution, murder and enforced disappearance have been rampant for decades, and perpetrators enjoy near total impunity. The Volume III Number 4 | 3 former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra’s campaign against drugs resulted in an estimated 2,800 extrajudicial killings during his first three months in office. In 2004, Mr. Somchai Neelaphaijit, a prominent human rights lawyer, was removed from his car on a main road in Bangkok by five policemen and has not been seen since. Mr. Neelaphaijit had submitted a complaint to the National Human Rights Commission and Royal Thai Police regarding a case on torture victims in Southern Thailand shortly before his disappearance. In 2014, Karen rights activist Porlajee “Billy” Rakchongcharoen was apprehended by national park officials following his support for a lawsuit accusing authorities of torching the homes of 20 families in Kaeng Krachan National Park in Petchaburi province.

Land rights defender Den Kamlae from the Khok Yao community in Chaiyaphum province has been missing since April 2016. In 2015, Khok Yao community received eviction notices from the government, on the grounds that it was illegally occupying forestland. Across Thailand, those who defend their lands, forests and communities are targets for violence by state authorities and business interests. In a rush to promote economic growth, the state has privileged large companies and corporations despite social and ecological costs, and the costs to the lives of those who the state should be protecting. In neighboring Lao PDR (Laos), the state functions with virtually no checks and balances among legislative and judicial structures and institutions. Key decisions about laws and policies concerning all aspects of society and the economy are made by the Politboro of the Lao Peoples’ Revolutionary Party (LPRP) and the Party Central Committee, and endorsed with little debate by a National Assembly. Public scrutiny of and participation in law, policy and other decision-making processes are practically absent. The LPRP has firmly anchored the nation’s development to rapid economic growth and expansion of the monetized economy, driven overwhelmingly by foreign investment and the extraction of natural resources.

As in Cambodia, high-ranking military officials have partnered with politically connected business people (domestic and foreign) to run lucrative (largely illegal) logging operations. All land is owned by the state, which continues to grant land concessions to investment companies for commercial plantations, mining and property development without proper independent environmental and social impact assessments, and adequate compensation for affected peoples.

Lao citizens are expected to comply with the decisions of the Lao Government and those who dare question or protest risk facing arrests, incarceration, “reeducation,” or worse. Notable exceptions to the rule of LPRP law are high-ranking party members and their families, who have amassed massive wealth through commissions on investment and infrastructure projects (many of which are tied with foreign aid) and business deals that are outside the law

In December 2012, Sombath Somphone, a respected member of Laos’ civil society and proponent of participatory development and education, was abducted on a busy street in Vientiane. Caught on CCTV camera, the abduction sent waves of shock and fear inside the country and abroad, and triggered unprecedented international expressions of concern and calls for prompt governmental action. The case has not been investigated by government authorities and is acknowledged as an enforced disappearance by the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (UNWGEID).3 Somphone’s abduction drew attention to other cases of disappearances in which government authorities at some level were implicated, but that have not been documented because local people are scared and reluctant to share information. The victims’ families and other Lao citizens who face or witness injustice remain silent because they have no legal recourse, no confidence that they will receive justice, and are fearful that speaking out will endanger the victim as well as their own families.

Threats, intimidation, violence and abuse of power are not new to the majority of the people in Asia, nor is impunity a novel issue. Over the past two decades however, these have escalated to alarming levels because of a powerful nexus of political and business interests, and increasingly regressive laws that criminalise those who resist or even speak out against land grabbing, deforestation, mining, dams, human rights violations and social-economic injustice. Narratives of economic growth, progress, nation building, national security, social stability, peace and even happiness are used as justifications by governments to silence dissent and opposition. Institutions and structures of justice are becoming instruments of repression as laws and decrees are amended or introduced to control the exercise of citizenship, while judicial proceedings are manipulated by those with wealth and political power.

Where judicial and administrative mechanisms are ineffective, those in power resort to direct threats and violence through the military, para-military, police, mobs and private contractors. Most times, perpetrators go free by virtue of their association with those in power. Even when the actual perpetrators who shoot the gun or hold the knife are caught, those that masterminded and ordered the attacks remain virtually untouchable; this is not true justice. They remain free to plan, order more violence and perpetuate threats and criminalisation.

To exist in a world in which development serves the needs of those it aims to serve, we need a system in which critical voices can be heard, and those defending human dignity are not repressed. States and societies must demonstrate strong commitments to protecting fundamental rights and freedoms for everyone, not only for those that political-economic elites deem acceptable. The escalation of impunity is systemic: it subverts the foundation and very notion of human rights, and collective potential to conceptualise alternative futures. We must promote pluralistic narratives of well-being and progress, and put an end to the criminalisation of dissent, to attacks against those who exercise their rights to defend their lives and futures, and to the impunity of those who mastermind, order and perpetrate these crimes.

Footnotes: 1 A 2012 Human Rights Watch report estimated that over 300 people had died in politically motivated killings since 1993. 2 For more information see: https://www.globalwitness.org/en/reports/dangerousground/ 3 For information about this case see: www.sombath.org