By Walden Bello*

(This is a composite version of articles that originally appeared in MEER on March 19, 2023 and The Nation on March 4, 2023).

Japan and the Philippines hold the distinction of being the countries in Asia where the US has had the deepest military footprint, the first as a result of having lost the Pacific War nearly 77 years ago, the second owing to military conquest at the turn of the 20th century.

Their place as strategic locations of American power has come to the forefront in a very dramatic fashion as the United States escalates its military containment of China. Earlier this month, the government of Ferdinand Marcos, Jr, announced it was going to give the United States four more military bases in addition to the five it now has. In Japan, the US command announced that US marine units armed with missiles will be deployed to remote Yonagoni island in the passage separating Japan from Taiwan, presumably to interdict Chinese naval vessels in the event of conflict. Also, the Kishida government also announced that it will raise military spending to 2 per cent of gross domestic product, from the traditional 1 per cent.

In short, both countries have been promoted to the unenviable status of being frontline states in Washington’s Cold War against China.

The Geopolitical Context

The reason this is happening is that the US-China relationship that was once a de facto alliance has turned bitter, dangerous, and unpredictable. After the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991, the US military began to see China as a potential threat to its unipolar status. However, the need to enlist China as a partner in America’s “war on terror” and, more important, the importance of China as a source of cheap labor to US transnationals and cheap products to American consumers took priority over strategic concerns in Washington’s calculations for almost three decades. But with Donald Trump’s coming to office in 2017, Washington’s posture towards Beijing changed from accommodating its global rise to containing China.

In the space of four years, the Trump administration named China an “economic aggressor;” declared a trade war on Beijing; initiated a technological war by banning the use of telecommunications equipment from Chinese firms like Huawei that were deemed national security risks; sought to change the character of China’s state capitalism by demanding a reduced role for the state in the Chinese economy; aimed to decouple China and the US by ending the US’s dependence of China for manufactured goods and China’s dependence on the US for high technology; and put an end to Washington’s benign approach to the TNC-China alliance by discouraging US TNC’s from investing in China and explicitly asking them to leave China and re-shore to the US.[1] American corporations were routinely denounced by Trump officials like former Trade Adviser Peter Navarro as accomplices of China’s destruction of the US’s manufacturing base.

Realizing that they had, like Frankenstein, created a monster with their devil’s bargain of trading technology for short-term profits, many key US TNCs backed Trump’s crusade, bringing to a dramatic close the 25-year-long China-TNC alliance.

Trump steered away from the corporate accommodation with China towards the Pentagon’s view of China as the US’s main global rival, making provocative moves such as installing the THAAD anti-missile defense system in South Korea over Beijing’s protests, deploying intermediate range missiles in the Pacific after the US withdrew from the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in 2019, and heightening aggressive US naval patrolling in the South China Sea.

Upon his assumption of office in 2021, Joseph Biden moved to repair damaged ties with Washington’s allies in order to bring US policy back to a multilateral from a unilateral track. The prime objective, however, was the same: to isolate China. Biden kept Trump’s high tariffs on China and his allies led a successful effort in Congress to pass the Chips and Science Act, which appropriated $250 billion to build up the US’s manufacturing and technological edge to counter China, “embracing in an overwhelming bipartisan vote the most significant government intervention in industrial policy in decades,” as one account put it.[2] The administration then followed up on Trump’s blocking telecommunications technology transfer to Chinese firms like Huawei with a far-reaching ban on the export of advanced microchips to China and on the employment of US citizens and permanent residents in Chinese firms involved in the design and manufacture of artificial intelligence chips, graphic processing units, and central processing units.

Equally important, on the diplomatic front, Biden has been able to obtain a consensus among US allies that China is a rival that threatens the primacy of the west and that the struggle against it would require coordinated political and economic action. Ever since the Russian invasion of the Ukraine early in 2022, Russia, an ally of China, has served as a proxy for China for the purpose of mobilizing NATO and the European Union in an anti-China alliance, a campaign that Washington has carried out successfully. This has had major benefits for the Washington’s aim to isolate China militarily in the Asia Pacific, where NATO vessels from the United Kingdom, France, and Germany have joined US, Australian, South Korean, and Japanese ships in so-called “freedom of navigation” patrols in the South China Sea.

A combined economic, diplomatic, and military posture against Beijing was articulated in the administration’s National Security Strategy unveiled in late October 2022, which Biden himself summed up as identifying China as the “most consequential geopolitical challenge” faced by the United States.[3] National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan said the significance of the document was that the “post-Cold War era is over.” That era had been marked by détente and cooperation between China and successive US administrations.

It was not lost on Beijing that the US document was a declaration of enmity short of war.

Japan as Frontline State

Being a frontline of the new Cold War that is will have major consequences for Japan. Japan has the distinction of being the third biggest economy in the world but also one of the least sovereign when it comes to the possession and use of force, the monopoly of which, Max Weber wrote, is the defining feature of a state. The foundation of the security relationship between Japan and the United States rests is the Peace Treaty of 1951 that was renegotiated in 1960. John Foster Dulles, the US Secretary of State who presided over the treaty negotiations characterized it as a “continuation of the occupation by other means.”[4] This description is apt since, as one defense expert reminds us over 70 years later, the treaty and its administrative annex “officially granted the United States the ‘rights, power, and authority’ within and adjacent to the facilities it controlled, including land, airspace, and territorial waters. This meant that the US military could station troops and material, collect intelligence, and stage regional military exercises when and how it saw fit. Second, the agreement guaranteed the United States access to Japanese ports and airports, and gave the US military the right to use all public utilities and services in Japan. Third, in the event of imminent or actual hostilities, the Japanese government was obligated to consult the US government ‘with a view to taking necessary joint measures for the defense of that area.’ These administrative agreement clauses meant that, while Japan was sovereign, it didn’t have a true monopoly on the legitimate use of force within its territory. This monopoly was ceded in, in part, to the US government.”[5]

With Japan’s status as an economic powerhouse, it is easy to forget that it continues to be, as Dulles put it, a militarily occupied country. There are some 70,000 US troops in approximately 85 bases and major facilities that are spread out on 31,000 hectares throughout the country, from Misawa Air Force Base 400 miles north of Tokyo to the vast US base complex that occupies nearly one-fourth of the island of Okinawa.[6] Because Okinawa makes up only 0.6 per cent of Japan’s land area but accounts for nearly 75 per cent of US military facilities, it is often easy for the rest of the country to pass off the military occupation as an “Okinawa issue.”

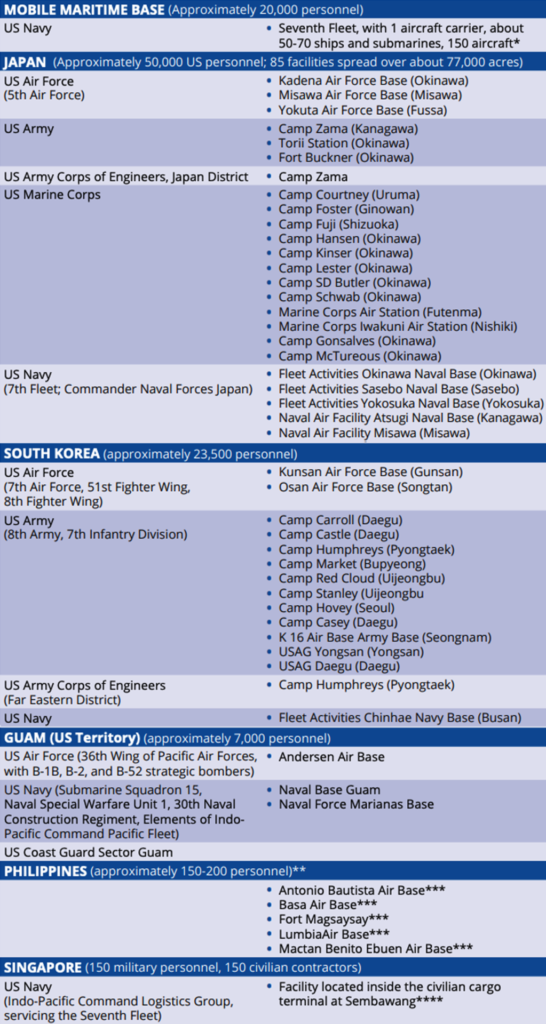

US Military Bases in the Asia-Pacific

*Occasionally supplemented with another carrier and other ships based in US West Coast

**These are mainly Special Forces personnel engaged in assisting Philippine troops against Islamic fundamentalist militant groups in Mindanao and Sulu. US personnel numbers temporarily swell to several thousands during joint US-Philippine military exercises.

***The US-Philippine Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) allows the US to use and have operational control over nominally Philippine bases for diverse activities, including stockpiling war materiel, an arrangement that allows both governments to circumvent the Philippine Constitution’s ban on foreign military bases. The Philippine government announced the termination of the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) with the United States in February 2020, placing the status of EDCA and the bases in limbo.

****Governed according to “access agreement” with the government of Singapore.

Sources:

- Military Bases Overseas, https://militarybases.com/overseas/, accessed Jan 12, 2020.

- Commander, 7th Fleet, https://www.c7f.navy.mil/About-Us/Facts-Sheet/, accessed Jan 12, 2020.

- US Forces Japan, https://www.usfj.mil/, accessed Jan 15, 2020.

- US Forces Korea, https://www.usfk.mil/, accessed Jan 15, 2020.

- “Naval Base Guam,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naval_Base_Guam, accessed Jan 15, 2020.

- “Andersen Air Force Base, Guam,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andersen_Air_Force_Base, accessed Jan 15, 2020.

- Rambo Talambong, “PH, US Armed Forces Open Balikatan 2019,” Rappler, April 1, 2019, https://www.rappler. com/nation/227138-philippines-us-armed-forces-open-balikatan-2019, accessed Jan 10, 2020.

- Seth Robson, “Facility for US Forces Opens on Philippines Main Island, Stars and Stripes, Jan 31, 2019, https:// www.stripes.com/news/pacific/facility-for-us-forces-opens-on-philippines-main-island-another-slated-forpalawan-1.566695, accessed Jan 9, 2020.

- Manny Mogato, “Despite Duterte Rhetoric, US Military Gains Forward Base in PH, Jan 31, 2019, https://www. rappler.com/thought-leaders/222309-analysis-us-military-gains-forward-base-philippines-duterte-rhetoric, accessed Jan 9, 2020. Bill Hayton, The South China Sea: The Struggle for Power (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), p. 231

That is an unfortunate illusion since most of the other bases in other parts of the country are essential parts of the US war machine, in particular, Yokosuka Naval Base, near Yokohama, which is the homeport of the US Seventh Fleet that serves as the backbone of the American naval presence in the contested South China Sea. Simply by virtue of being the main territorial host of the US regional garrison in Western Pacific, Japan is integrally implicated in Washington’s containment strategy towards China that is now in full swing.

Aside from more intense preparations for war carried out by US forces within their Japanese garrison state that are largely without the purview of government of Japan, what else should be expected?

Well, first of all, the Japanese public should expect the costs for maintaining US troops and bases to rise, under Washington’s pressure. Indeed, the Diet last year already raised the so-called host-nation support, passing a 1.05 trillion yen ($8.6 billion) budget for the next five years.[7]

Then, as mentioned earlier, the Kishida government is raising military spending from the traditional 1 per cent to 2 per cent of GDP in the next five years, or 43 trillion yen. That figure comes to 13 per cent of total projected national tax revenues.[8] Meeting the demands of a more aggressive containment policy will involve increasing severe fiscal strains. With the demands of militarization outrunning national revenues, the government will have to borrow more from the private sector, leading its indebtedness to rise above the current 220 debt to GDP ratio.

Third, there is going to be a deeper engagement by the Japan Self Defense Forces in military operations outside Japan, a move that has been prepared by the so-called Abe Doctrine of “collective security.” This means going beyond peacekeeping operations to actual combat deployments on air, sea, and land. Aside from the violation of the letter and spirit of Article Nine of the Constitution, there is also the issue of the impact of the strains on the JSDF of a more offensive orientation. Japan’s demographic crisis is already having a major effect on the JSDF, contributing to its struggling to meet its recruitment quotas. As one analyst has noted, “the JSDF is scraping together whomever it can get and hoping technology fills the gap.”[9] Being forced to participate in extended operations in East Asia and beyond will strain the JSDF’s capabilities, and one of the key casualties will likely be non-offensive operations like rescue operations and disaster relief, which have been responsible for the JSDF’s positive image in the eyes of many.[10]

Will Japan’s Self Defense Forces be deployed for offensive operations? Members of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces’ infantry march during the annual SDF ceremony at Asaka Base, Japan, October 23, 2016. (Photo by Kim Kyung Hoon/Reuters)

Finally, there is likely to be a renewed effort to do away with Article 9, with more active support from Washington, which, has long regretted General Douglas MacArthur’s command to write it into the Constitution and, along with the Japanese far right, has been the biggest backer of Japan’s rearmament. With the older generations that were committed to Article 9 becoming less influential as a source of public pressure, it is not at all certain that this symbol of Japan’s pacifist culture will not fall, eliminating the key psychological barrier to Washington’s renewed containment militarism. In any event, as it has been over the last decade, the struggle over Article 9 will be polarizing and destabilizing.

The Japanese Self Defense Forces faces recruitment problems owing to the country’s aging population. (Photo by Walden Bello)

Frontline State Philippines

Now, the Philippines.

If indeed geography is destiny, the Philippines is Exhibit A. Perhaps no one captured the enduring strategic value of the archipelago better than General Arthur MacArthur, father of the more famous Douglas, who led the expedition that subjugated the country in 1899. The Philippines, the elder MacArthur wrote,

is the finest group of islands in the world. Its strategic location is unexcelled by any other position in the globe. The China Sea, which separates it by something like 750 miles from the continent, is nothing more nor less than a safety moat. It lies on the flank of what might be called several thousand miles of coastline; it is the center of that position. It is therefore relatively better placed than Japan, which is on a flank, and therefore from the other extremity; likewise India, on another flank. It affords a means of protecting American interests which with the very least output of physical power has the effect of a commanding position in itself to retard hostile action.[11]

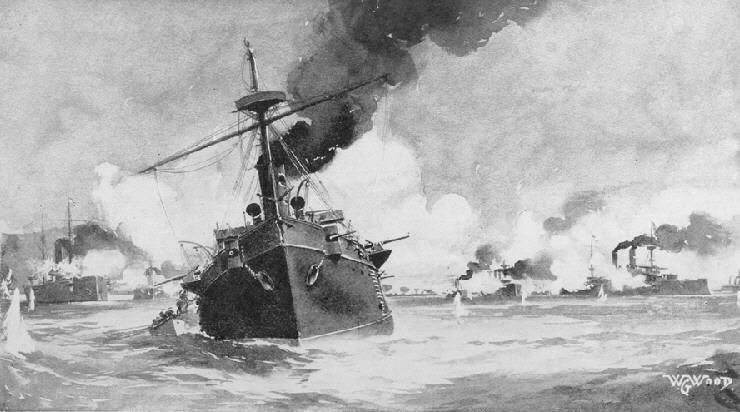

The Battle of Manila Bay on May 1, 1898, which saw the Asiatic Squadron of the US Navy under Commodore George Dewey destroy a decrepit Spanish fleet, extended the strategic reach of the US thousands of miles fromthe country’s western borders, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Battle_of_Manila_Bay_by_W._G._Wood.jpg

These words have a very contemporary ring as the Philippines becomes a key pawn in Washington’s increasingly militarized strategy to contain China. As noted in the beginning, the new administration of President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr, will provide the US with four more bases, in addition to the five it already operates.

Reacting to recent events, many people are asking why the US bases are back since they still have memories of the US leaving the huge Clark Air Force Base and Subic Naval Base when the Philippine Senate rejected a renegotiated bases agreement in 1991.

The main reason has to do with China’s military moves in the South China Sea in the early and mid-1990’s.

The most significant step Beijing took was the creeping occupation of Mischief Reef, which lay within the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of the Philippines, under the pretext of building “wind shelters” for Chinese fishermen.[12] In response, Washington and Manila negotiated a new military agreement. The Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA), completed in 1998, provided for the periodic deployment of thousands of US troops to participate in military exercises with their Filipino counterparts. This was followed by what eventually became a permanent deployment of US Special Forces in the island Basilan in the Southern Philippines as part of President George W Bush’s War on Terror.[13] The post-Marcos 1987 constitution banned the permanent presence of foreign troops, so to get around the ban, the Special Forces and other US troops were portrayed as being in the country on a “rotational basis,” in order to engage in exercises with Filipino troops and provide them with “technical advice,” and without authority to use firearms except in self-defense.

“First and Second Island Chains” off the Asian land mass provide opportunities for the US to contain China with firepower from bases located there and present China with a strategic dilemma, https://www.defensenews.com/ global/asia-pacific/2016/02/01/powers-jockey-for-pacific-island-chain-influence

China’s territorial incursions became bolder and more frequent in the 2000’s and, in 2009, it submitted to the United Nations its controversial Nine-Dash-Line map that claimed as Chinese territory some 90 per cent of the South China Sea, including significant sections of the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ’s) of five Southeast Asian states: Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, and the Philippines. Things came to head during the administration of President Benigno Aquino III, from 2010 to 2016. Chinese coast guard vessels began aggressively driving off Filipino fishermen from their traditional fishing grounds, one of the richest of which was Scarborough Shoal, some 138 miles from the Philippines, which lay within the 200 mile EEZ of the country. After a one and half month long confrontation Chinese and Philippine vessels, the Chinese ended up seizing the shoal.

The response of Aquino III was twofold. The first was to elevate the issue to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague, which eventually declared invalid China’s claims. Not surprisingly, China did not recognize the PCA’s ruling, but the court’s opinion did amount to moral victory for the Philippines. But the administration’s more consequential move was to enter into the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) with the Obama administration, which placed no limits on the number of bases, weaponry, and troops that the US could have or could bring into the Philippines. Presented as an executive agreement and not as a treaty, the deal drew anger from nationalists who demanded Senate concurrence. The Supreme Court ruled, however, that not being a treaty, the deal did not need the approval of the Senate.

At this point, we are obliged to answer, before proceeding any further, why China was acting in the way it was acting in the South China Sea. The answer is related to events in Taiwan, which lies at the northern edge of the South China Sea, in the mid-1990’s.

While Beijing considers its sovereignty over Taiwan non-negotiable, its strategy has been to promote cross-straits economic integration as the main mechanism that would eventually lead to reunification. In Taiwan, however, being tough on Beijing plays well with voters, and nothing plays better than the threat to declare independence or assuming the trappings of a sovereign power. When Taiwanese leaders display such behavior, Beijing has felt constrained to put them in their place. In certain circumstances, Beijing has felt compelled to go beyond words and resort to sending missiles to the waters around Taiwan. Taiwan President Lee Teng Hui’s visit to the United States in 1995 was one such occasion, as was, more recently, the hosting of former US House of Representative Nancy Pelosi in August 2022 by Tsai Ing-wen, the current head of state. While both events created diplomatic crises, the first had momentous strategic consequences.

Ivan Marc/Shutterstock.

When China launched missile drills to teach Taiwan a lesson in 1995 and 1996, the Clinton administration sent two supercarriers, the USS Independence and the USS Nimitz, to the Taiwan Straits in March 1996. This was the biggest display of US power since the Vietnam War and it was intended to underline Washington’s determination to defend Taiwan by force. Washington’s intervention was cold water splashed on Beijing’s face, for it showed just how vulnerable the coastal region of east and southeast China, the industrial heart of the country, was to US naval firepower.

USS Independence heads for the Taiwan Strait in a show of force against Beijing during the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis. (Creative Commons)

It was from this realization that China’s strategy in the East and South China unfolded over the next two decades. As analyst Gregory Poling notes, “One can draw a straight line from the PLAN’s [People’s Liberation Army Navy] humiliation in 1996 to its near peer status with the US Navy today.”[14] Overall, China’s strategic posture is defensive, but in the East and South China Seas, it is engaged in the “tactical offensive” aimed at enlarging its defense perimeter against US naval and air power. As defense analyst Samir Tata writes, “As a land power, the Middle Kingdom does not have to worry about the unlikely possibility of a conventional American assault on the mainland via amphibious landing by sea, parachuting troops by aid, or an expeditionary force marching through a land invasion route. What it is vulnerable to is US control of the seas outside China’s 12-nautical mile maritime boundaries. From such an over-the-horizon maritime vantage point, the US navy has the capability to cripple Chinese infrastructure along the eastern seaboard by long-range shelling, missiles, and unmanned aerial bombing.”[15]

In response to this dilemma, the Chinese have evolved a strategy of “forward edge” defense consisting of expanding its maritime defense perimeter and fortifying islands and other formations in the South China Sea that it now occupies or has seized from the Philippines with anti-aircraft and anti-ship missile systems (A2/AD, or “anti-access/area denial” in military parlance) designed to shoot down hostile incoming missiles and aircraft in the few seconds before they hit the mainland. Though defensive in its strategic intent, what has enraged Beijing’s neighbors is the unilateral way Beijing has gone about implementing A2/AD, with little consultation and in clear violation of such landmark agreements as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas that accords them EEZ’s.

The Puzzling Duterte Interlude

The coming to power of Rodrigo Duterte in 2016 was heralded as bringing about a major shift in US-Philippine relations. Dismissive of concerns about the mounting extra-judicial executions in his bloody war on drugs, Duterte successfully harnessed that undercurrent of resentment at colonial subjugation that has always coexisted with the admiration of things American in the Filipino psyche to promote a populist anti-Americanism. He also aligned with China, with his administration downplaying the significance of the Hague ruling and refusing to take up the cudgels for Filipino fishermen shooed away from their traditional fishing grounds by Chinese Coast Guard vessels.

When it came to the US, however, Duterte was more bark than bite. He did not interfere with the close relationship between the US and Philippine military, which came into play when US Special Forces assisted Philippine troops in the bloody retaking of the southern city of Marawi from Muslim fundamentalists in 2017.[16] Neither did he follow through on his vow in 2020 to abrogate the Visiting Forces Agreement. Indeed, by the end of his term, Duterte was extolling the VFA, voicing approval of AUKUS security pact joining Australia, Britain, and the United States, reestablishing the Philippines-United States Bilateral Strategic Dialogue, and launching expanded joint military exercises with the US.[17] While not repudiating his close relationship with China, Duterte ended his presidency in June 2022 on a cordial note with Washington that contrasted sharply with the bitter row with President Barack Obama that launched his term.

Washington on the Offensive

Beijing’s unilateral acts in the South China Sea has provided Washington with ammunition in its containment strategy towards China, which has been operative since the Obama years. But Washington’s rhetoric now elicits worries among some ASEAN governments that they are being drawn into a regional confrontation that is not in their interest. Particularly alarming has been a recent leaked memo from General Mike Minihan, who heads up the US Air Mobility Command, that asserts, “My gut tells me will fight in 2025.”[18] Minihan, it bears noting, is not the first to predict conflict with China in the immediate future. Adm. Michael M. Gilday, Chief of Naval Operations, said in October last year that the US should prepare to fight in 2022 or 2023.[19] Even earlier, the head of the US Indo-Pacific Command, Admiral Philip Davidson, said that the Chinese threat to Taiwan would “manifest” in the next six years, by 2027.

Even without such statements, the level of hostile activity in the South China Sea has been alarming. During a visit to Vietnam I made as a congressman in 2014, top Vietnamese officials expressed concern at how, owing to lack of rules of engagement, a ship collision by an American and Chinese ship “playing chicken”—according to them a common occurrence–could immediately escalate to a more intense level of conflict.

Chinese Coast Guard vessel shoots water cannon at Vietnamese patrol boat in dispute over the location of an oil rig in waters both claim. (Government of Vietnam photo)

Like the Philippines, Vietnam has criticized Beijing’s moves and its vessels have engaged Chinese Coast Guard ships in water-hosing jousts in the South China Sea. The aggressive posture of the Biden administration, however, has led Hanoi to affirm a posture of neutrality in the brewing superpower confrontation. In a recent visit to Beijing, the Secretary General of the Vietnamese Communist Party, Nguyen Phu Truong, assured Chinese President Xi Jin Ping that his government would continue to hew to its “Four Noes” foreign policy approach in the region, that is, that Vietnam would not join military alliances, not side with one country against another, not give other countries permission to set up military bases or use its territory to carry out military activities against other countries, and not use force – or threaten to use force – in international relations.[20]

Blackmail as diplomacy

But the Philippines is not Vietnam and Marcos Jr. has no record of discerning the national interest in his years as a politician, much less advocating or standing up for it. On that front he even falls short of Duterte, who claimed he became a nationalist while in college in the 1960s.

What he’s very conscious of, though, is how high the stakes are for himself and his family should he make the wrong decision in the intensifying conflict between Washington and Beijing.

Members of the Marcos dynasty are said to have been apprehensive about visiting the United States ever since they last left it in the early 1990s, when they’d come as exiles there following the uprising that ousted Ferdinand Marcos, Sr, in 1986. The reason is a standing $353 million contempt order against Marcos Jr., related to a US court judgment awarding financial compensation from the Marcos estate to victims of human rights violations under the dictatorship. Ever since the contempt order was issued by the US district court in Hawaii in 2011, Marcos has avoided complying. A new judge extended the contempt order to January 25, 2031, which would render Marcos vulnerable to arrest anytime he visits the United States during his term, which ends in 2028.

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr, poses with US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin after granting the US four more bases to supplement the five it already has in the strategic archipelago. (Photo by Reuters)

Marcos also cannot be unaware of how the US, with its global clout, has often been able to freeze the assets of people linked to regimes considered undesirable by the US, the most recent example being the holdings of Russian oligarchs connected to President Vladimir Putin in the wake of Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine. The Marcos family has some $5 to $10 billion in landholdings and other assets distributed throughout the world in such places as California, Washington, New York, Rome, Vienna, Australia, Antilles, the Netherlands, Hong Kong, Switzerland and Singapore. Being on the wrong side of the United States, especially in a dispute as central as the China-US conflict could have devastating financial consequences for the Marcos dynasty.

With this veritable sword of Damocles hanging over him, Marcos Jr., is not someone who would dare cross Washington. Indeed, when it comes to negotiating an independent path between two superpowers, he is the wrong person at the wrong place at the wrong time – which is another way of saying that from Washington’s point of view, he’s the right person at the right place at the right time.

Conclusion

Let me end by saying that It is difficult at present to see Japan and the Philippines adhering to a neutral position like that of Vietnam in the conflict between the United States and China. The US military is much too entrenched in them territorially, institutionally, and in terms of the symbiosis among elites.

Japanese protest against the US bases in Okinawa. (Image from Picture-alliance/AP Photo/S. Kambayashi)

Still one has to be wary of deterministic analysis. Is a more towards a more neutral or at least more nuanced strategic position nearly foreclosed? Washington’s reckless rush to drag the Philippines and Japan to its containment strategy may, in fact, backfire, with consequences different from that that Washington desires. As the peoples of both countries begin to experience the dangers and economic costs of participating in the Contain China Alliance, this might lead to the reinvigoration of the peace movement in Japan and the popular movement in the Philippines that was probably the key factor that brought down the curtains on Subic Naval Base and Clark Air Force Base in 1991.

*Walden Bello is currently a visiting senior researcher at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies of Kyoto University, international adjunct professor of sociology at the State University of New York at Binghamton, and co-chair of the Board of Focus on the Global South. As a member of the House of Representatives of the Philippines from 2009 to 2015, he authored two joint resolutions with the late nationalist Senator Miriam Santiago-Defensor seeking the abrogation of the US-Philippine Visiting Forces Agreement.

—–

[1] See, among others, White House Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy, China’s Economic Aggression Threatens the Technological and Intellectual Property of the United States (Washington DC: White House, June 2018.

[2] “Senate Passes $280 Billion Industrial Policy Bill to Counter China,” New York Times, July 27, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/27/us/politics/senate-chips-china.html, accessed July 30, 2022.

[3] US National Security Strategy Calls Competition with China Its ‘Most Consequential Geopolitical Challenge,’” South China Morning Post, Oct 13, 2022, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/3195754/us-national-security-strategy-calls-competition-china-its-most?utm_source=Facebook&utm_medium=share_widget&utm_campaign=3195754&fbclid=IwAR36RPie_EO9BIMRgiZvWvKVnxhchiH9QlXjS5r5GEIirdkboJg7lbJALqA, accessed Oct 30, 2022.

[4] Victor Cha, Power Play: The Origins of the American Alliance System (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), p. 158.

[5] Ibid., pp. 158-159.

[6] See Walden Bello, Trump and the Asia Pacific: The Persistence of Unilateralism (Bangkok: Focus on the Global South, 2020), pp. 16-17.

[7] Hiroshi Asahina, “Japan Greenlights $8.6 Bn to Host US Troops,” Nikkei Asia, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Japan-greenlights-8.6bn-to-host-U.S.-troops

[8] Estimates by Tomoko Sakuma, Feb 14, 2023.

[9] Tom Phuong Le, Japan’s Aging Peace (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021), p. 84.

[10] Ibid., pp. 85-86

[11] Quoted in William Manchester, American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur [New York: Dell, 19780, pp. 48-49

[12] Marites Vitug, Rock Solid: How the Philippine Won its Maritime Claim against China [Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2018, pp. 309-310.

[13] Walden Bello, “A Second Front in the Philippines,” The Nation, Feb 28, 2002, https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/second-front-philippines/

[14] Gregory Poling, On Dangerous Ground: America’s Century in the South China Sea (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022), p. 166.

[15] Samir Tata, “China’s Maritime Great Wall in the South and East China Seas,”” The Diplomat, Jan 24, 2017, https://thediplomat.com/2017/01/chinas-maritime-great-wall-in-the-south-and-east-china-seas/

[16] Manuel Mogato and Simon Lewis, “ÜS Forces Assist Philippines in Battle to End City Siege,” Reuters, June 10, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-philippines-militants-usa-idUSKBN191068

[17] Derek Grossman. “Duterte’s Alliance with China is Over,” Foreign Policy, Nov 2, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/11/02/duterte-china-philippines-united-states-defense-military-geopolitics/

[18] US Four-Star General Warns of War with China in 2025,” Reuters, Jan 29, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/us-four-star-general-warns-war-with-china-2025-2023-01-28/

[19] Sean Durns, “War Could be Sooner than Expected,”Taipei Times, Nov 4, 2022, https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2022/11/04/2003788234

[20] Cyril Ip, “Çhina-Vietnam Ties: Beijoimg Reaasured by Hanoi’s Vow to Reject All Military Alliances, Analysts Say,” https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3198034/china-vietnam-ties-beijing-reassured-hanois-vow-reject-all-military-alliances-say-analysts