Mary Ann Manahan, Focus on the Global South

March 20, 2012

“Privatization is collapsing. We have to be ready with what we will replace it with.”—

David MacDonald, Municipal Services Project co-director

For the last decade, the water justice movements from around the world have been struggling against the privatization and commercialization of water. Many campaigns were successful. For example in 2001, a grassroots and people’s campaign booted out Suez in Cochabamba, Bolivia. But the big challenge for the movements is always to be one step ahead of the privateers. When you have won the struggle, successfully kicked out the corporate private sector, what do you do? What do you put in place? Well, the work never really stops. It is equally challenging, if not difficult, to sit down and agree on a collective political project, that is constructing and building alternatives that are people-centered, inclusive, participatory, democratic, equitable, sustainable, and transparent.

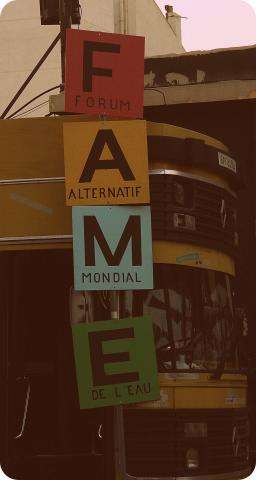

The water justice movements have risen to the occasion. Not only because we need to figure out how to provide water to the poor and waterless but also of the collective aspiration to change the dominant corporate water discourse and change the ‘flow’. The last five years saw a new movement to reclaim, redefine, and reconstruct public options and paths for water governance. The Alternative World Water Forum (www.fame2012.org) was a fertile ground for sharing such experiences, strategies, initiatives and campaigns.

Vote for the Public

On March 15, the Municipal Services Project, a global initiative that systematically explores alternatives to the privatization and commercialization of service provision in the health, water, sanitation and electricity sectors, launched the publication Alternatives to Privatization: Public Options for Essential Services in the Global South (www.municipalservicesproject.org).The publication is the first global survey of its kind that provide rigorous and robust platform for evaluating different alternatives, identifying what make them successful and allowing for comparisons across regions and sectors.

The alternatives on water cover examples such as innovative models of public service delivery in Tamil Nadu, India, which are neither private or old-style public. The Change Management Initiative of the Tamil Nadu Water Board in India, a public utility that provides drinking water to 60 million people and the delivery of irrigation water to the farms of more than one million families engaged into a change management process involving shift in perspectives and attitudes of its water engineers and transformation of the institutional culture using a process-oriented participatory methodology based on their traditional practice called Koodam, a Tamil word for gathering and social space, and for consensus that implies harmony, diversity, equality and justice. The experiment transformed the water engineers and providers from technical people into “managers of the commons”, at the center of which is real partnership between the government and communities. This democratization experiment, which started 5 years ago is now making waves outside the state of Tamil Nadu and last year, they just created a national level platform for public water operator partnerships that involves communities.

But the notions of the public have also been expanded and reclaimed by citizens and people. In Colombia, social participation has taken on new forms (www.censat.org). Danilo Urrea of CENSAT shared their initiative on the national public-community partnership which led to the strengthening of communal aqueducts in Colombia. Communities were systematically organized and provided with the necessary technical, legal and economic support to ensure that good quality water is delivered to both the rural and urban areas. Women also played a vital role as leaders in the strengthening and structuring of the aqueducts.

Similarly, new form of public-community or upstream-downstream partnerships in New York City enabled farmers to implement a new farming program that is compatible with a healthy watershed and pure, quality water for the city (www.focusweb.org/content/water-commons-water-citizenship-and-water-security). Using the philosophy a “good environment will produce good water”, the New York City Water and Sewerage System, a public utility that supplies water to 9 million people, invested public resources into the farmers’ watershed protection program, which ensured not only clean water to the city but also the survival of small farming in the rural area.

Even unions such as Public Services International (PSI), one of the largest international federations of public sector unions with millions of members from around the world, talk about social unionism. According to David Boys, PSI’s utilities expert, “unions have a role to play in ensuring quality service but we defend the rights with you so you can benefit from our quality service; the challenge is how to create real participatory mechanisms that bring together various actors and concerned groups.”

All these cases speak of the power of participation not in terms of time-limited consultation or mere tokenism. But as an ethic in which citizens and people get their hands dirty in the details of water source protection, linking the urban and rural, among others, which often are left with technocrats and decision makers.

Remunicipalization Works!

Another important trend now is the increasing number of remunicipalization which emphasizes that privatization is not irreversible. The publication, “Remunicipalisation: Putting Back Water into Public Hands”, edited by Martin Pigeon, David McDonald, Olivier Hoedeman and Satoko Kishimoto (www.tni.org/tnibook/remunicipalisation), “while remuncipalisation is by no means simple, the cases in Malaysia, Paris, Dar es Saalam, Buenos Aires and Hamilton prove that public management can offer services that the private sector could never deliver”. Remunicipalization, according to the authors, “is a credible, realistic and attractive option for citizens and policy makers dissatisfied with privatisation”.

The tides are indeed turning. The return of Paris’ water services to the municipalities in January 2010 made a significant break from the commercial dominance of the French multinationals in the water sector. By establishing the single public operator, Eau de Paris, France was able to restructure, institute important reforms and reclaim public interest. According to Anne Le Strat, the deputy mayor of Paris in charge of water, some initial advantages have already been observed as a result of remunicipalization. One is the big profits, an estimated 35 million Euros that the reform has produced and re-invested in water services; two, the lowered cost of water per cubic meter (at one Euro compared to the 260 percent increase with the private company); and finally new services are underway.

The changing tides also travel to Asia. In Indonesia, civil society, unions and Jakarta’s citizens are calling for the termination of the city’s contract with Suez. Twelve years after the privatization of water in Jakarta, Suez has failed to deliver its promise of adequate water supply through pipe connections in the city. The residents had resorted to over-extraction of groundwater which created new environmental problems. A recent report of the Supreme Audit Board of Indonesia (BPK) concluded that the private contract is non-transparent, unfair and void. Jakarta is the last big city in the global South where Suez still has a concession contract. The termination of this contract, therefore, will have a big political impact not only in Jakarta but all over the world.

Overcoming Challenges

A clear message from the people’s world water forum is the need to have a clear, long-term vision of the kind of public water management that will replace privatization. There is still much to be done in terms of articulating and implementing progressive models of water management and governance. Learning from the past and thinking of creative ways to achieve the “future we want” are but necessary. A stable institutional, policy, legal framework and political will are needed for such alternatives to develop and flourish. Public-public partnerships and public-community partnerships are often vulnerable to the manipulation of international financial institutions, financing and free trade agreements. The corporate private sector will always attempt to hijack not only the language of civil society and social movements but also alternative proposals.

But whatever the challenges maybe, one thing’s for sure, these alternative models are charting new paths and options for the world’s waterless population. As mentioned above, there is a growing movement to critically defend, reclaim, redefine, and harness the public such as the Reclaiming Public Water Network, the Platform for Public-Community Partnerships in Latin America, the European Water Network, and Municipal Services Project. And they will certainly be forces to reckon with. Corporate private sector, you better watch out!

Mary Ann Manahan is a program officer/researcher-campaigner with Focus on the Global South. She is part of the Reclaiming Public Water Network, a loose and horizontal international network of activists, trade unionists, public water operators, and academics promoting progressive, democratic, and people-centered models of public water management such as Public-Public and Public-Community Partnerships. She participated at the Alternative World Water Forum through the support of TNI. She maybe reached at [email protected]

![[Press Release] There can be no justifications for land grabbing!” social movements and CSOs tell World Bank, UN agencies and governments](https://focusweb.org/wp-content/themes/Extra/images/post-format-thumb-text.svg)