Raphael Baladad

“Kung walang corrupt, walang mahirap” (If there is no corruption, there is no poverty) was the rallying call behind Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III’s Presidential campaign in 2010, with the promise of purging crooks from government ranks and leading the nation toward “tuwid na daan” (the straight path). Six years later, with the Aquino Administration’s failure to come up with effective solutions to poverty and inequality, its ineffectiveness in confronting urgent crises, and the outbreak of corruption scandals, Rodrigo Duterte emerged as the popular alternative—a solution for the swelling discontent on the broken promises of liberal reformism. Duterte vowed a tougher and more decisive stance in addressing the biggest let-downs of his predecessor; among which is combatting corruption. Three years into a Duterte Presidency, hundreds of public officials have been put on a chopping block, shamed and criminalized for dishonesty. But behind the hyped achievements of Duterte’s anti-corruption campaign, the controversial re-appointments of corrupt personnel he himself dismissed and his propensity to detach inner circles from liabilities following accusations of dishonesty, casted doubts on Duterte’s resolve in confronting pervasive corruption. While the public demands for greater transparency and accountability, Duterte demolishes the institutions that safeguard it from powerful and influential opportunists—who now scramble to enrich themselves through the administration’s big-ticket projects. The question now is, will Duterte’s crusade against corruption bring better political and governance outcomes for the country?

The prevalence of cronyism and plunder under Marcos’ dictatorship left an indelible mark on our national psyche that places corruption as the root cause of the Philippines’ underdevelopment and stagnation. The claims of liberal reformism; “that re-establishing democracy, fighting corruption, and improving the efficiency of governance should be the country’s top priorities”[1] has been used by post-1986 EDSA administrations as their main narrative in sustaining the legitimacy of their hold to power. On one hand, efforts to promote a level of transparency and accountability in governance through anti-corruption campaigns abounded, aiming to appease the people’s strong abhorrence to thieving public officials. On the other, these campaigns also became tools for regimes to delegitimize political opponents. Though corruption has long permeated politics and state affairs, corruption charges remain a weak spot[2] for all players—whose longevity in the political arena is determined by public perceptions on reputation or credibility. From Ferdinand Marcos’ ouster in 1986 to Joseph Estrada’s in 2011, corruption has always been a rallying point for regime change, either through color revolutions or elections.

The nation’s clamor for better political and economic outcomes is guided by the aspiration of attaining a “cleaner” government. The same can be observed with the 16 million, oft-cited “protest” vote that seated Duterte as President in 2016, by promising a route towards national salvation. But what makes Duterte different from his co-runners and predecessors is his narrative: that, “given weak institutions, only a violent strongman rule can bring political order to the country.”[3] For Duterte, the fight against corruption progresses alongside waging the war on drugs–his administration’s priority campaigns. His disgust of government thieves goes with the same line as drug pushers and addicts, threatening to “skin them alive or to shoot them on sight”, stressing his position of zero tolerance.

As the President sees it, fighting corruption with a remorseless clenched fist is the only way towards the change he promised: to restore public trust; to enhance bureaucratic efficiency in delivering services; and to improve investor confidence. A few days before his first State of the Nation Address, Duterte signed the Executive Order for the Freedom of Information (FOI), a move that reinforced his bold campaign pronouncements and earned him praise from all fronts at the onset of his presidency. Introducing stiffer penalties under the Anti-graft and Corrupt Practices Act, and expanding the power of the Presidential Anti-Corruption Commission were also lauded, particularly by the private sector who were optimistic about Duterte’s strong stance in creating a policy environment that would facilitate an ease in doing business. Duterte’s boldness and bravado enabled him to bask in high approval ratings for his performance in addressing corruption, which hovered between 70% and 80% since 2016.

Heads will roll

Also in the past three years, Duterte has fired, removed, resigned, replaced, or rejected scores of government employees and officials due to allegations of corruption or mismanagement of public funds. Among the notable are members of his cabinet, particularly Interior and Local Government Secretary Ismael Sueno, Information and Communication Technology Secretary Rodolfo Salalima, Justice Secretary Vitaliano Aguirre II, and Tourism Secretary Wanda Teo. Teo resigned out of conflict of interest when the Commission on Audit questioned the ₱60 million[4] tourism ad placements in a television show hosted by his brothers Ben and Erwin Tulfo. Later, Teo was also questioned for purchasing ₱2.5 million in duty free goods via tourism funds. Salalima, as former Vice President of Globe Telecom, tendered his resignation as communications chief out of “delicadeza” and conflict of interest. Duterte later on admitted that he forced Salalima to resign due to alleged preferential treatment.[5] Aguirre resigned from his post after losing credibility and public trust,[6] following the dismissal of drug charges against self-confessed drug lord, Kerwin Espinosa and his alleged involvement in the Bureau of Immigration bribery scandal. Sueno was dismissed by Duterte for “loss of trust and confidence” due to purchasing reportedly overpriced firetrucks from Austria, allegedly accepting gambling money, and using government funds for personal purposes.

Even in firing officials, Duterte has a “penchant for the dramatic”, announcing beforehand where his hatchet might fall, alongside outbursts of exasperation and expletives. His pronouncements are intended to bolster his commitment towards eradicating corruption, and to instill fear in government officials on the repercussions of being found corrupt. Jesus Dureza, former chief of the Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process (OPAPP), resigned after Duterte fired two officials under his wing due to allegations of corruption. Dureza later said that he took command responsibility[7] and resigned for his failure to curb corruption in his office. Peter La Vina, Duterte’s former campaign advisor, also resigned as National Irrigation Authority (NIA) chief due to rumors accusing him of extortion and receiving kickbacks from government projects. Though Duterte did not name La Vina as the official he threatened to fire after a meeting with NIA officials, La Vina said that his resignation was to spare the President from these embarrassing stories. While sacking officials at a whiff of dishonesty may be laudable, Duterte’s anti-corruption posturing leans more towards the display of power and control, rather than systematically dismantling the practices that allow corruption to persist. This was further manifested in the lack of follow through investigations, particularly on the abovementioned officials, and in the filing of actual charges and the questionable re-appointments Duterte made for some notable personnel he had earlier axed.

No second chances?

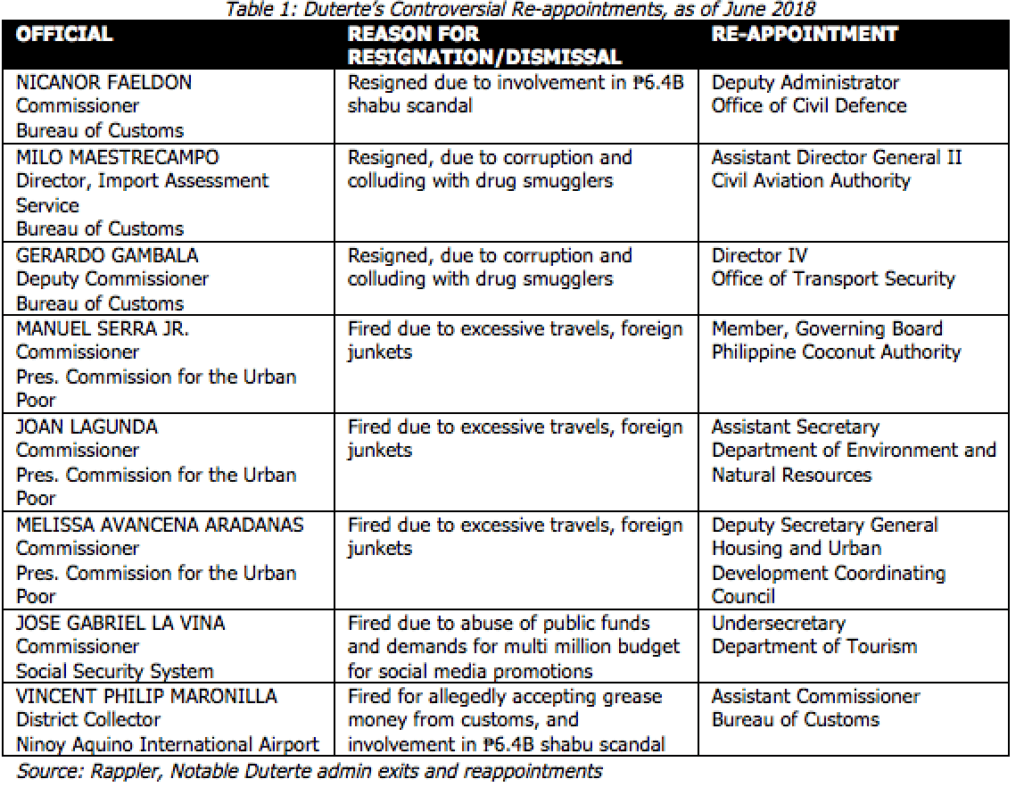

Amidst Duterte’s firing spree, various reports have flagged the controversial “recycling” of officials, which raised serious doubts on his anti-corruption campaign. Among them is Nicanor Faeldon, the former Bureau of Customs (BOC) Chief who, despite being accused by the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency of involvement in the ₱6.4 billion shabu (methamphetamine) smuggling controversy, was subsequently appointed as Deputy Administrator in the Office of Civil Defense. Feldon’s two other colleagues were also reinstated to a different office immediately after being cleared of their involvement by the Department of Justice. The said BOC officials are among the many personnel that Duterte re-hired despite corruption charges or allegations.

Confronted with this issue, the Malacañang says it is the “President’s prerogative to reassign people,”[8] and that the reappointments likely mean that “they have been found by Duterte as innocent of the allegations.”[9] The anti-corruption campaign has enabled a positive projection of Duterte as being decisive on high profile cases when courts have been slow in exacting accountability from dishonest officials. The case of La Vina and Dureza stressed this even more, as it exemplifies Duterte’s willingness to fire even his closest political allies. His strongman stance, however, has proven to be superficial when he exposed his partiality as judge and executioner in the reappointment of allegedly corrupt officials. Though Duterte has been vague on the reasons behind the re-appointments, his motives appear to be strategic – a concession for silence, or detachment of officials from future probes that might hurt the legitimacy of the administration.

Duterte’s partiality in condemning officials with a so called “whiff” is more evident with the case of Special Assistant to the President (SAP) Christopher “Bong” Go. In 2018, Bong Go was linked by media reports[10] to a ₱4.6 billion public works contract that was questionably awarded to CLTG Builders, a company owned by his kin. Go was also implicated in an anomalous re-routing of contractors for the Combat Management Systems (CMS) of the two vessels under the Frigate Acquisition Project (FAP) worth almost ₱16 billion. Malacañang cleared Go’s involvement in the FAP after an “internal” probe, despite the glaring evidence. Duterte later on admitted that he was the hand behind the sudden change of contractors. Malacañang has also been silent on Go’s involvement in the controversial public works contracts, saying that it is up to the Senate to pursue further investigations.[11] In addition, recent reports also flagged Go’s alleged usage of public funds in his Senatorial campaign, with his spending reaching ₱422 million as opposed to his declared net worth of ₱12 million.

Bland outcomes

Budget Secretary Benjamin Diokno recently found himself in hot water after being accused of attempting to bribe lawmakers with ₱40 billion[12] in exchange for their silence on the controversial insertions in the 2019 budget. Malacañang, however, was quick to defend Diokno, saying that cabinet executives would never resort to bribery.[13] In March this year, after the congressional probe, Diokno was appointed as Bangko Sentral (Central Bank) Governor.

Apart from being undeniably close and loyal to the President, the only job security government it seems is by being part of the club that manages the country’s economy. With Duterte freely saying “that he doesn’t understand economic matters”, his economic managers have since had a free rein in implementing a policy agenda (see article The Price of Taming Inflation) that reaped public protest for leaning towards elite/corporate interests in government. Among the various stakeholders that stands to gain in the campaign against corruption, Duterte attempts to please business investors the most. In a 2017 survey by the World Economic Forum, corruption is among the top three business barriers in the country—along with inefficient bureaucracies and inadequate infrastructure[14]—and has considerably deteriorated the government’s capacity to raise the needed revenue for developmental functions and programs. Duterte himself lamented that corruption in government has reached pandemic proportions, “hampering the nation’s economic growth by 10 to 15 years in achieving the same level as our other Southeast Asian counterparts.”[15]

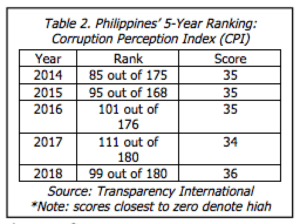

Despite Duterte’s best efforts, the outcomes of his anti-corruption campaign remain dismal in terms of boosting investor confidence. Based on the latest Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) of Transparency International, the Philippines had no noteworthy improvement in global rankings within the past five years. In 2017, Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) fell by half from the previous year to ₱105 billion.[16] Investment approvals also declined by 38%[17] in the opening months of 2018, following the country’s lowest mark in the CPI in the past five years.

Despite Duterte’s best efforts, the outcomes of his anti-corruption campaign remain dismal in terms of boosting investor confidence. Based on the latest Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) of Transparency International, the Philippines had no noteworthy improvement in global rankings within the past five years. In 2017, Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) fell by half from the previous year to ₱105 billion.[16] Investment approvals also declined by 38%[17] in the opening months of 2018, following the country’s lowest mark in the CPI in the past five years.

Watchdogs under fire

The low scores from the CPI could be attributed to the ceaseless attacks against the institutions that safeguard transparency and accountability in government. While Duterte constantly vows to intensify his anti-corruption campaign, he unashamedly jokes about “kidnapping and torturing” Commission on Audit (COA) personnel. Confronted with criticisms, the palace justified Duterte’s jokes as mere expressions of “exasperation and vexation” on the stringent rules applied by COA that delayed priority government projects. Unsurprisingly, Duterte laid began his tirade a month after COA released the report on the ₱34 billion underutilized budget of the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), citing the “delay or non-implementation of infrastructure projects” as the prime reason for low disbursement. Duterte had also joked about throwing a COA auditor down the stairs for reporting doubtful purchases and fake bid documents under Ilocos Norte Governor Imee Marcos.[18] Other delayed government projects include a ₱12 billion National Irrigation Authority project, and the Yolanda Permanent Housing Program of the National Housing Authority worth ₱1.5 billion, which COA flagged due to the mounting budgetary costs incurred by ineffective planning and implementation, violations in procurement law, and the awarding of projects to questionable contractors. Duterte, however, has repeatedly blamed COA for the underspending and delays, saying that the COA “has not contributed to national development.”

Though the COA’s reports and findings have been instrumental in Duterte’s firing of certain officials, the institution did not spare Malacañang from its scrutiny. The COA also questioned the utilization of the government’s confidential and intelligence funds, which increased by 400% in three years from ₱420 million to more than ₱4 billion.[19] The said funds are for intelligence gathering and other confidential purposes that may have impacts on national security, making them difficult to audit. The Office of the President received a sizeable chunk of around ₱2.5 billion[20] in 2018, to be used for the administration’s campaign against drugs, criminality, and corruption.

Duterte has also condemned the Office of the Ombudsman for its investigation into his family’s alleged hidden wealth, following earlier accusations from Senator Antonio Trillanes IV on undeclared assets amounting to ₱2.4 billion[21] acquired through alleged ghost employees in Davao City. Ombudsman chief Conchita Carpio-Morales earlier inhibited from the case, due to her relation as aunt-in-law of Presidential Daughter Sara Duterte, but later said that “she will abide by her Constitutional duty to probe Duterte’s wealth.”[22] Stemming from Sen. Trillanes’ complaint is another investigation into Presidential Son and Davao City Vice-Mayor Paolo Duterte’s alleged mis-declaration of his Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net worth (SALN),[23] possible graft charges, and his involvement in a ₱6.4 billion shabu smuggling case. The mounting pressure against the President and his family had repercussions for Morales when she was accused by Duterte of being part of a conspiracy to remove him from office. Duterte also threatened to file an impeachment complaint against Morales, to lift Senator Trillanes’ amnesty,[24] and to create a commission for counter-investigations against the people behind the probe. Eventually, the complaints against Duterte were terminated by the Office of the Solicitor General due to insufficient evidence.

Recently, however, Duterte expressed that “What my family earns outside government is none of your business, actually,”[25] hitting against the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism’s (PCIJ) report[26] on questionable increases in his family’s wealth and the discrepancies in the SALN. The PCIJ also flagged several of Sara and Paolo Duterte’s inconsistencies in declaring investments or ownership of several corporate entities. Defending his position against PCIJ’s findings, Duterte says “investigative journalists are like that, it’s all about money for them.”

Duterte’s tirades against persons or institutions that challenge his integrity reinforces common misconceptions among his supporters who are active in defending his reputation. It also empowers other citizen-based movements to become his watchdogs that, in time of need, could also attack political opponents and critics. The Volunteers Against Crime and Corruption (VACC), though earnest in its advocacy to support victims of heinous crimes in the past, have now been mobilized by Duterte to play a key role in criminalizing dissenters in government. In 2017, the VACC filed cases against newly elected Senator Leila De Lima for allegedly receiving payoffs from prison-based drug cartels, eventually leading to her detention. Senator De Lima was known to strongly criticize Duterte for human rights abuses long before the war on drugs commenced in 2016. Senator Trillanes and Ombudsman Morales also faced raps from the VACC during the ongoing investigation into Duterte’s wealth, accusing them of sedition, treason, bribery, graft and corruption, and betrayal of public trust. Its founding Chairman, Dante Jimenez, despite calling for Duterte’s disqualification in the 2016 elections, has been appointed to lead the Presidential Anti-Corruption Commission.

The tactics are clear: to discredit and demolish institutions that impede the exercise of absolute power, and create new ones that would reinforce legitimacy and control in government (see article Stopping the slide: Democracy and Human Rights Decline under Duterte). Beneath the veil of a twisted anti-corruption discourse that he weaved through dramatic pronouncements and sheer charisma, Duterte conveniently eluded almost every attempt by opposing forces to tarnish his integrity, at least, for his die-hard supporters. But Duterte did very little to dismantle the culture of corruption that emanates from the untouchables in the legislature.

The ghost of PDAF

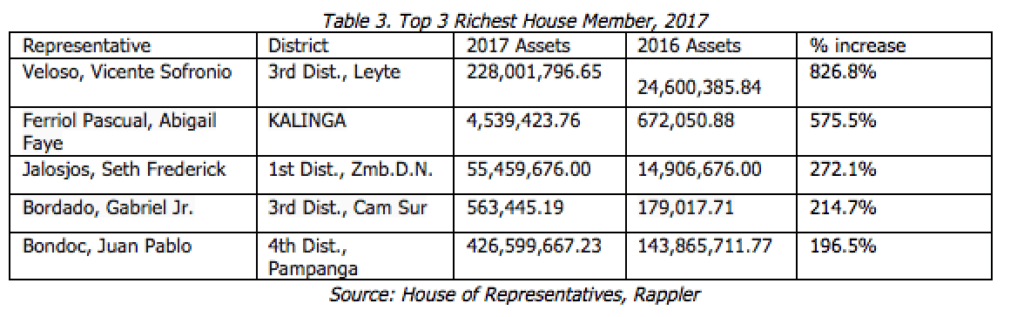

Duterte enjoys very strong support from the House of Representatives’ majority, effectively mobilizing them to push the administration’s policy campaigns forward with much ease. But when it comes to curbing corruption, most legislative officials are bent on preserving the status quo. Recently, the House of Representatives drew flak for instituting stiffer rules for public releases of SALNs. In the wake of Duterte’s FOI executive order in 2017, various investigations have revealed questionable asset increases of several lawmakers, some reaching billions of pesos in wealth, and others doubling their assets within a year.

Lawmakers enriching themselves in office through “pork barrel”[27] is a widely known and but scarcely understood issue that has evolved over time with “complicated rules involving many steps and players, and strange changes”[28] since it started in the 1990s as “simple and short provisions in budgetary law.”[29] Starting out as the Countrywide Development Fund (CDF), the allocation “aims to support small local infrastructure and other priority community projects which are not included in the national infrastructure program.”[30] The fund, however, has been known to be exploited by lawmakers for projects designed to please voters, or to siphon public funds for personal gain. The term “pork barrel” was attached to such allocations when executive branch utilizes it to secure support and gain personal favors or patronage from the legislature. Due to issues arising from CDF’s utilization, the allotment was subsequently changed into the Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF) in 2000 and since then, debates emerged on its validity as a constitutional exercise of the congressional “power of the purse.”[31]

The abuse of PDAF again sparked controversy after the Fertilizer Fund Scam in 2004, when presidential candidate Panfilo Lacson accused President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo of routing ₱728 million from the Department of Agriculture’s 2003 budget, and dispersing the funds to several districts for the procurement of overpriced fertilizer a few months shy of the 2004 National Elections.

In 2013, the Supreme Court (SC) ruled that the PDAF was unconstitutional, resulting from the investigations on the “pork barrel” scam that implicated several Senators and Congressmen (see box 1). The SC ruling mandated a cash based budgeting system—since “lawmakers are not project implementors”[32] —funds should not be given directly to them in a lump sum, but instead coursed through relevant government agencies.

Resulting also from the PDAF scandal investigations, former President Aquino was charged with the usurpation of legislative powers[33] for the implementation of the Disbursement Acceleration Program (DAP), an economic stimulus program enacted by President Aquino to authorize the release of ₱72 billion in funds through the withdrawal of unobligated allotments from various government agencies in 2012.[34] Beyond the DAP, Aquino was also criticized for his ₱449 billion[35] Special Purpose Fund (SPF). Tagged as Aquino’s personal pork, large chunks of the SPF include an unprogrammed ₱139 billion,[36] and a ₱49 billion[37] budgetary support for government corporations.

Resulting also from the PDAF scandal investigations, former President Aquino was charged with the usurpation of legislative powers[33] for the implementation of the Disbursement Acceleration Program (DAP), an economic stimulus program enacted by President Aquino to authorize the release of ₱72 billion in funds through the withdrawal of unobligated allotments from various government agencies in 2012.[34] Beyond the DAP, Aquino was also criticized for his ₱449 billion[35] Special Purpose Fund (SPF). Tagged as Aquino’s personal pork, large chunks of the SPF include an unprogrammed ₱139 billion,[36] and a ₱49 billion[37] budgetary support for government corporations.

In 2018, Senator Panfilo Lacson warned of the looming return of pork barrel in the 2019 proposed budget, following the ₱50 billion insertions made by several Representatives to expand agency budgets for “pet” projects. Senator Lacson’s allegations created an impasse as the Senate refused to sign the Lower House version of the ₱3.75 trillion 2019 General Appropriations Bill (GAB), forcing the government to run on a reenacted budget by the turn of year. A Congressional probe ensued, headed by Rules Committee Chairman Rep. Rolando Andaya who later on accused Secretary Diokno of instigating a total of ₱75 billion in insertions[38] to the budget of the Department of Public Works and Highways. Though Diokno defended the so-called “budgetary adjustments” as a “prerogative of Congress to realign funds for their projects,”[39] Rep. Andaya claimed that the DPWH projects funded by the ₱75-billion addition were already been bid out before 2018 ended, under an early procurement circular issued by the Department of Budgetment and Management[40] He also pointed out that the contractors who have advanced the “kick-backs” of lawmakers and officials are now demanding refunds. Rep. Andaya also reported that DPWH Secretary Mark Villar was unaware that ₱51 billion was added to his department’s budget in 2019

Duterte himself denied knowledge of any insertions, but justified the adjustments “as something the DBM have prepared in advance Senator Lacson has also called out Rep. Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo as the hand behind the insertions, which happened a few months after ouster of Rep. Pantaleon Alvarez as Speaker of the House. Rep. Andaya, however, was quick in defending Arroyo, pointing out that she herself spotted the budget irregularities during Rep. Alvarez’ term as Speaker. Earlier media reports, however, have flagged a ₱2.4 billion allocation for Speaker Arroyo’s district in Pampanga in the House approved version of the 2019 GAB.

Despite the investigations, the Congress subsequently ratified the 2019 budget due to delay of government projects, with the House of Representatives itemizing a ₱98 billion lump sum to new projects. The Senate on the other hand, also made “post-bicam” realignments amounting ₱79 billion,[41] with Senate President Tito Sotto saying the said amount was outside the agreements[42] during the bicameral conference.

These recent turn of events come dangerously close to the 2019 midterm elections, which unsurprisingly explains the scramble for pork by lawmakers and the sizeable budget increases in the 2019 General Appropriations Act. While this sordid episode in Congress awaits a reasonable conclusion, the acquittal of Sen. Ramon Revilla in December 2018 from graft and plunder charges by the Sandiganbayan has again raised doubts on Duterte’s stance against corruption—along with Senators Jinggoy Estrada and Juan Ponce Enrile released earlier through million-peso bails. Janet Lim-Napoles, the PDAF scam’s mastermind, was placed under “witness” protection by the Department of Justice (DOJ) in 2018, despite being convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment. While Duterte has repeatedly pronounced his interest to uncover the truth behind the PDAF scam, he was silent about Revilla’s recent acquittal, with the Palace announcing that it “bows down to the judgment of the Sandiganbayan.”[43]

Duterte was known to prod Ombudsman Morales into “winding up” the cases against three former Senators, accusing her of delivering “selective justice”. Months before his acquittal, Revilla announced his plan to run for Senator in the 2019 elections and urged the endorsements of the Hugpong ng Pagbabago (HNP)—a regional party formed by Sara Duterte that serves as the united political platform for the administration’s bets for the senatorial race—and from Duterte himself. Though Duterte, as chairman of the ruling Partido Demokratiko Pilipino–Lakas ng Bayan (PDP-Laban) party, deferred from endorsing Revilla, Estrada, and Enrile, saying that they “came too late”, Sara Duterte defends HNP’s endorsement claiming that “there is no finality to the PDAF case and no guilty verdict has been rendered for the three.”[44]

Duterte’s anti-corruption: convenient in its inconsistency

By discrediting an already eroding “good governance” narrative instilled by post-1986 EDSA liberal reformism, Duterte presented his “strong governance” as the only option to save a government in stagnation. Though Duterte has effectively transformed and gained ground in the anti-corruption discourse, his actions still abide by the same dirty politics the country has witnessed in the past three decades. While he vows to dismantle the system that allowed corruption to persist, Duterte also worked towards forming alliances with the same political groups and players, establishing a new order that would ensure a lasting hold on power.

Technically, the better result of Duterte’s anti-corruption campaign is confined mostly in offices under the executive branch where he can effectively exercise his power as president; such as appointing or dismissing officials at a “whiff” or on a whim. In other branches, Duterte wields influence through the same patronage schemes he vowed to destroy at the onset of his presidency. The strong populist support he enjoys from his captured mass base have enabled Duterte to detach himself from any accountability from accusations of corruption or occasions of mismanagement in his programs. He effectively diffuses public pressure to the people he seated in his podium of power, or unlucky officials who have fallen out of his favor. But like the usual “traditional politician”, Duterte never forgets those who are loyal to him, shielding them also from any administrative or criminal liability when caught red-handed trying to enrich themselves, or trying to accumulate more power at the expense of the people’s purse. What his power and influence cannot reach, he tries to tarnish through his distorted anti-corruption narrative, or through other unconventional means that would keep any opposition scorned or ostracized. Like the experienced political warlord that he is, he successfully weaponized the discourse to create wider divisions in public opinion, and to push the boundaries of what people can accept as the new normal in politicking.

But giving Duterte reasonable doubt, even if he stayed true to his ideal of delivering changes on how the country is governed, his anti-corruption campaign is still funneling its efforts in the wrong direction.

While he despises the oligarchs, the anti-corruption discourse he rides on is the same discourse that “gives ruling elites something to blame for the country’s less-than-impressive development over the past hundred years, without having to point the finger at themselves as a whole.”[45] While corruption definitely needs to be condemned, it has become a useful scapegoat that diverts the public discourse from arriving at real political or economic alternatives. But then again, Duterte is part of the ruling elite, like his often demeaned predecessor, despite his rhetoric and successful packaging as an outsider.#

_________________

[1] Thompson, Mark R., Bloodied Democracy: Duterte and the Death of Liberal Reformism in the Philippines, in: Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, (2016) 35, 3, 39–68. Accessed 20 April 2019: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/186810341603500303

[2] Bello, W. et al, The-Anti Development State: The Political Economy of Permanent Crisis in the Philippines. Focus on the Global South, University of the Philippines College of Social Science and Philosophy (2004).

[3] Ibid

[4] Cordero, T. COA red flags PTV’s P60-M payment to Tulfo’s Program for airing DOT ads. Accessed 09 April 2019: https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/news/nation/651594/coa-red-flags-ptv-s-p60-m-payment-to-tulfo-s-program-for-airing-dot-ads/story/

[5] Gita, R. Duterte admits he fired DICT chair Salalima: Sunstar Philippines (2017). Accessed 09 April 2019: https://www.sunstar.com.ph/article/166584

[6] Ballaran, J. Aguirre resigned due to public’s loss of trust in him. Accesses 09 March 2019: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/980581/aguirre-resigned-due-to-publics-loss-of-trust-in-him-official

[7] Kabiling, G., Wakefield, F. Dureza cites ‘command responsibility’ for resignation, OPAPP corruption allegations. Accessed 09 March 2019: https://news.mb.com.ph/2018/11/28/dureza-cites-command-responsibility-for-resignation-opapp-corruption-allegations/

[8] Associated Press. Tough on corruption? Not for many officials rehired. Accessed 09 March 2019: https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2018/07/06/1830962/tough-corruption-not-many-fired-officials-rehired

[9] Ranada, P. Malacanang defends reappointments of customs officials tagged as corrupt. Accessed 09 March 2019: https://www.rappler.com/nation/189325-malacanang-defends-reappointment-customs-officials-corrupt

[10] Mangahas, M., Ilagan, C. Firms of Bong Go kin, top contractors: Many JVs, delayed projects in Davao. Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism. Accessed 15 March 2019: https://pcij.org/stories/firms-of-bong-go-kin-top-contractors-many-jvs-delayed-projects-in-davao/

[11] Romero, A. Palace: Up to Senate if it wants to probe gov’t deals of Bong Go kin. Philippine Star. Accessed 15 March 2019: https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2018/09/12/1850956/palace-senate-if-it-wants-probe-govt-deals-bong-go-kin

[12] Andaya Accesses Diokno of ‘bribery try’, budget chief cries false: ABS-CBN News. Accessed 15 March 2019: https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/02/08/19/andaya-accuses-diokno-of-bribe-try-budget-chief-cries-false

[13] Duterte govt doesn’t resort to bribery-palace exec. Manila Times. Accessed 15 March 2019: https://www.manilatimes.net/duterte-govt-doesnt-resort-to-bribery-palace-exec/508590/

[14] In various reports on Duterte’s speeches.

[15]Kabiling, G. Duterte to sustain war vs frugs, corruption; boost economic growth. Manila Bulletin: Accessed 15 March 2019: https://news.mb.com.ph/2019/01/02/duterte-to-sustain-war-vs-drugs-corruption-boost-economic-growth/

[16] Vera, B. Foreign investment pledges plunge 37.9% in Q1. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Accessed 15 March 2019: https://business.inquirer.net/252116/foreign-investment-pledges-plunge-37-9-q1

[17] ibid

[18] Ranada, P. Duterte jokes let’s kidnap, torture COA personnel. Rappler. Accessed 16 MArch 2019: https://www.rappler.com/nation/220551-duterte-joke-kidnap-torture-commission-audit-personnel

[19] Rappler. Big chink of 2017 intel funds spent by only 3 institutions. Accessed 16 March 2019: https://www.rappler.com/nation/215397-national-government-confidential-intelligence-funds-spent-2017-coa

[20] Santos, E. Expenses of Duterte’s office up by ₱12.5 billion in 2017. CNN Philippines. Accessed 16 MArch 2019: http://nine.cnnphilippines.com/news/2018/07/06/Duterte-office-expenses-2017-commission-on-audit.html

[21] ABS-CBN News. Trillanes: Duterte a ‘fraud,’ didn’t declare P211M in . Accessed 15 March 2019: https://news.abs-cbn.com/halalan2016/focus/04/27/16/trillanes-duterte-a-fraud-didnt-declare-p211m-in-saln

[22] ABS-CBN News. Ombudsman reiterates constitutional duty in probing Duterte’s wealth. Accessed 15 March 2019: https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/10/01/17/ombudsman-reiterates-constitutional-duty-in-probing-dutertes-wealth.

[23] Tolentino, M. R., Paolo Duterte faces SALN investigations. Manila Times. Accessed 17 March 2019: https://www.manilatimes.net/paolo-duterte-faces-saln-investigation/407086/

[24] From inciting the Oakwood Munity in 2001, under President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.

[25] Burgos, N. Duterte: What my family earns outside of gov’t is none of your business. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Accessed 15 March 2019: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1104096/duterte-what-my-family-earns-outside-of-govt-is-none-of-your-business

[26] Simon F., Mangahas, M., Duterte, Sara, Paolo mark big spikes in wealth, cash, while in public office. Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism. Accessed 07 April 2019: https://pcij.org/stories/duterte-sara-paolo-mark-big-spikesin-net-worth-while-in-public-office/

[27] Nograles, P., Understanding the pork barrel. Congress of the Philippines. Accessed 15 March 2019: http://www.congress.gov.ph/download/14th/pork_barrel.pdf

[28] Macaraig, A., ‘Prok through the years: it got complicated. Rappler. Accessed 15 March 2019: https://www.rappler.com/nation/40965-pork-barrel-timeline-sereno-molo

[29] ibid

[30] Ibid

[31] ibid

[32] Rappler. FULL TEXT: SC PDAF ruling, justices’ opinions. Accessed 09 March 2019: https://www.rappler.com/nation/44379-full-text-sc-pdaf-ruling-concurring-opinions

[33] ABS-CBN News. Aquino should be charged with plunder over DAP – Panelo. Accessed 15 March 2019: https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/06/22/18/aquino-should-be-charged-with-plunder-over-dap-panelo

[34] ibid

[35] Doronilla, A., Special purpose funds ‘bigger monster’ for misuse. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Accessed 15 March 2019: https://opinion.inquirer.net/59377/special-purpose-funds-bigger-monster-for-misuse

[36] ibid

[37] ibid

[38] Diaz, J., P75 billion Diokno ‘insertion’ ends up as lawmakers’ ‘pork barrel’. Philippine Star. Accessed 15 March 2019: https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2019/02/13/1893288/p75-billion-diokno-insertion-ends-lawmakers-pork-barrel

[39] Yap, D., Diokno defends House prerogative to insert funds for projects. Philippine Daily Inquirer.

Accessed 15 March 2019: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1061922/diokno-defends-house-prerogative-to-insert-funds-for-projects

[40] ibid.

[41] Ropero, G. P79 billion realigned in 2019 national budget, Sotto says. ABS-CBN News. Accessed 15 March 2019: https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/03/10/19/p79-billion-re-aligned-in-2019-national-budget-sotto-says

[42] ibid

[43] Ranada, P. Malacañang ‘bows down’ to Sandiganbayan acquittal of Bong Revilla. Rappler. Accessed 16 March 2019: https://www.rappler.com/nation/218409-malacanang-statement-sandiganbayan-acquittal-bong-revilla-plunder-case

[44] Esguerra, D., Sara Duterte defends HNP’s endorsement of Estrada, Revilla. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Accessed 19 March 2019: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1084658/sara-duterte-defends-hnps-endorsement-of-estrada-revilla

[45] Bello, W. et al, The-Anti Development State: The Political Economy of Permanent Crisis in the Philippines. Focus on the Global South, University of the Philippines College of Social Science and Philosophy (2004).