Read the rest of the series at focusweb.org/tag/kaa70.

by Galileo de Guzman Castillo

V0025029 Geography: water spouts at sea, with rain. Coloured wood engraving by Charles H. Whymper. Wellcome Library, London. Creative Commons Attribution, CC BY 4.0

I hadn’t known that under our skins

There is a birth of a storm

And a wedding of rivulets

—Mahmoud Darwish, “The Reaction”

(translated by Sulafa Hijjawi, in Poetry of Resistance in Occupied Palestine, 1968)

The Asian-African Conference of 1955 in Bandung has often been cited as a watershed moment in global history as it facilitated the convergence of peoples united against colonialism and imperialism. The formative gathering in the provincial capital of West Java in Indonesia served as a cornerstone of Global South cooperation and solidarity that brought together representatives of colonized nations as they collectively sought ways to deal with a broad range of world problems. While the Bandung Conference itself only constituted a brief moment, it helped galvanize broad and rainbow movements for peace, non-alignment, and decolonization, riding along new waves of South-South solidarity.

The Bandung Spirit of anti-imperialism and post-colonial unity lives on, 70 years hence, and it is as important as ever to reignite and reimagine this Spirit in the current context.

Notwithstanding its shortcomings and imperfect outcomes, a revisit of the Bandung Conference confirms its significance and enduring legacy in demonstrating a counter against the hegemony of the imperial powers that still permeates across the globe in the present era. The principles that emerged in Bandung at the ‘end of the age of empire’ remain relevant in addressing global challenges, including when applied to the continuing struggles for peace, justice, self-determination, and liberation for Palestine and beyond.

The Bandung Conference and the Palestinian Question

There were already strong decolonizing and anti-imperialist impulses since the end of World War II and the unfolding of a geopolitical rivalry between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies. Asian and African nations had sought alternative ways of just global governance to achieve justice and development for their peoples shackled by colonialism for decades—even centuries for some.

Sovereign states that had been released from the fetters of imperialist colonialism and had gained their independence continued to fight for their rights to self-determination and sovereignty in various spaces, including in the then newly established United Nations (UN). Professor of Modern Arab Politics and Intellectual History Joseph Massad (2024) traced the debates on these questions that raged in the Third Committee of the UN General Assembly, with the colonizing countries led by the US insisting that self-determination pertained only to the ‘political’ while refusing to recognize economic self-determination of former colonized peoples.[1] Securing this legal right involves economic decolonization and achieving genuine national and economic sovereignty by charting their own paths to development based on their particular conditions.

In the middle of the Cold War tensions, more than 2,000 delegates from 29 countries—bound by their commonalities as recently decolonized nation-states within an international order shaped by the bi-polarized logic of the Cold War—gathered in Bandung in 1955. The gathering, spearheaded by the leaders of the five Asian states of Burma (Myanmar), Ceylon (now known as Sri Lanka), Indonesia, India, and Pakistan tackled several issues, on the top of which were peace, economic cooperation, human rights, and the self-determination of colonized peoples. The delegates, representing almost two-thirds of the population of the world, affirmed in their Declaration the centrality of self-determination to the post-war order as the “pre-requisite of the full enjoyment of all fundamental human rights.”[2]

Professor of Asia and Africa Studies Kweku Ampiah (1997) notes, “The one underlying theme that ran through the economic, cultural, and political objectives of the conference was a sense among the members, irrespective of their ideological orientation, that they would not be trapped with their experiences as ‘dependents’ or appendages of colonialism (…) Essentially, the spirit of the conference hinged on the determination of the member states to preserve their newly won freedoms and to reach out for more through their persistent opposition to colonialism and imperialism.”[3]

The Bandung Conference, despite having a limited number of delegates from a handful of African countries—Egypt, Ethiopia, Gold Coast (now known as Ghana), Liberia, Libya, and Sudan—tackled and denounced the system of apartheid in South Africa and the persisting colonial rule by France in Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. However, absent an official envoy from Palestine, it fell short on the Palestinian question.

Notwithstanding the absence of Palestinian voices in Bandung, the Palestinian cause was championed by the representatives from Syria, China, and Egypt, among others. Palestinian nationalist Ahmed Shukairy, who joined the Syrian delegation as its deputy head, made sure that his people’s case was properly represented in Bandung. At the same time, Egyptian President Gamal Abdul-Nasser underscored in his speech the injustice and aggression wreaked upon the Palestinian people who “were uprooted from their fatherland, to be replaced by a completely imported populace.”[4]

The grave structural injustices inflicted against the Palestinians included the adoption of the British Mandate for Palestine by the Council of the League of Nations in 1922, the stamping of approval by the UN of the partition plan that divided historic Palestine in 1947, and the subsequent en masse expulsion of the Palestinian peoples from their homeland. Under the eyes of the international community, all of these arbitrary decisions made by colonial powers on the lives and territories of an entire people continue to have lasting impacts on generations upon generations of Palestinians.

While the Bandung Conference explicitly declared “its support of the rights of the Arab people of Palestine” and called for “the implementation of the United Nations Resolutions on Palestine and the achievement of the peaceful settlement of the Palestine question,”[5] the limitations of the gathering was made evident with the tensions, disagreements, and constrained bases of unity among the delegates. Notwithstanding the difficulties with how the Bandung Principles were framed, they have come to serve as a critical benchmark on political self-determination, non-interference, national sovereignty, and peaceful coexistence. As Indian historian and journalist Vijay Prashad (2007) notes, despite “the infighting, debates, strategic postures, and sighs of annoyance, Bandung produced something: a belief that two-thirds of the world’s people had the right to return to their own burned cities, cherish them, and rebuild them in their own image.”[6]

Ultimately, the Bandung Conference laid the necessary groundwork for political, economic, cultural, and legal transformations for the Global South, and contributed, however limited, to the consolidation of a global decolonization movement with the advent of newly independent countries across the Global South shaping international law, institutions, and their futures.

Palestine in the Third World

The Conference of 1955 sparked the emergence of a “Spirit of Bandung,” an incipient force that facilitated the resurgence of a Third World awakening. The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in 1961 and the subsequent 1962 Conference on the Problems of Economic Development in Cairo became offshoots of Bandung, which eventually moved to include Latin America in the mid-1960s, embodied by initiatives like the Tricontinental Congress of 1966 in Havana, led by the Cuban revolutionary Fidel Castro. The Tricontinental Gathering saw the convergence of roughly 500 representatives from 82 countries and went on to form a movement that aimed to unite liberation struggles in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, which in many ways superseded the NAM set up at Bandung in the previous decade.

Diverse peoples espousing an anti-imperialist ideology came together within the Tricontinental framework that offered a critical analysis of global capitalism and racism, alongside a much more action-oriented focus than the preceding Bandung Conference. The Tricontinental also supported the Palestinian struggle from the outset, placed the Palestine issue to the forefront of the global political agenda, and allowed the Palestinians themselves to represent their own national cause in the process. Scholar and writer Suleiman Hodali (2024) chronicles how the “the anti-colonial struggle for Palestinian liberation became infused with a markedly global character, and the question of Palestine was reified as a definitive cause for an emergent Third World consciousness” and how “Palestine’s gradual entrenchment as a vanguard of Third World struggles also reveals how the lineages of Bandung endured and matured.”[7]

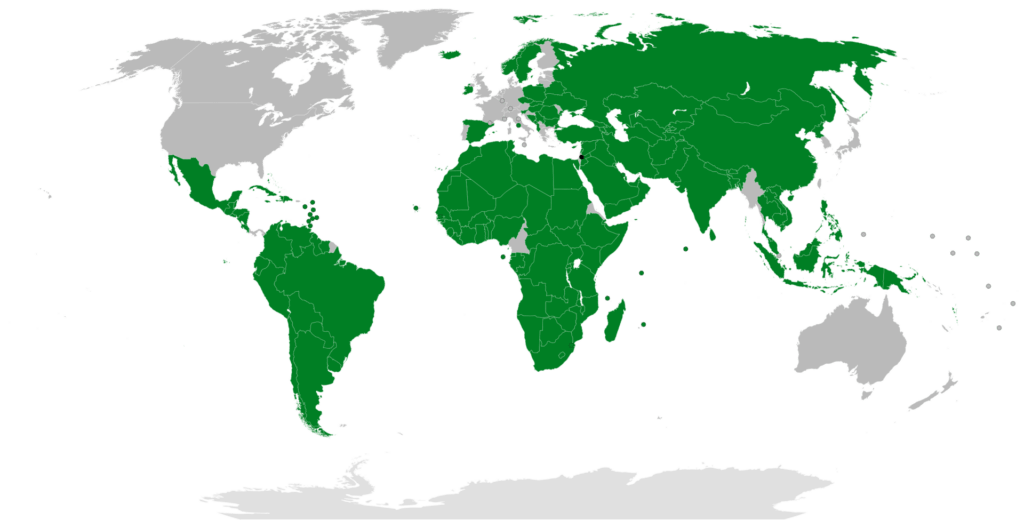

International recognition of the State of Palestine: Three-quarters of the United Nations (147 of the 193 UN member states) recognize Palestine as a sovereign state as of March 2025. Photo by Night_w, Wikimedia Commons, marked as public domain.

In 2005, in commemoration of the 50th year of the Bandung Conference, representatives of 89 countries gathered at the Asian-African Summit in the Indonesian cities of Jakarta and Bandung, where they drafted the Declaration of the New Asian-African Strategic Partnership. Unfortunately, the 2005 Declaration was merely a hollow echo of the Bandung Principles in 1955, without much refining, and therefore did not spark any fervor similar to the original Bandung that engendered a sense of collective strength—of peoples deciding their own destiny in the international order. Relatively speaking, the meeting also did not gain much visibility, nor was it given attention by the international community compared to the 1955 edition.

Ten years later, another Asian-African Summit was held again in Bandung, as a habba (surge) of resistance, violence, and protests engulfed Palestine and Israel. In their 2015 Declaration, the delegations deplored the fact that “sixty years since the Bandung Conference, the Palestinian people remain deprived of their rights, freedom and independence, and that millions of Palestinians are still living under occupation and as refugees, and that this historic injustice continues.”[8]

Arguably, the Bandung Conference and the subsequent Asian-African summits did not do much to advance their stated aims—for a myriad of reasons—including those that were already beyond the gatherings themselves. International lawyer Sahed Samour (2017) argues that as a conference, “Bandung entailed too many tensions and contradictions, leaving it almost inconsequential. The later emerging spirit of Bandung starting in the 1960s outshined the Final Communiqué of the conference. That spirit was materialized by a confident Palestinian leadership emerging in the 1964 Palestine Liberation Organization and by a radicalization of the Third World movement formed by dramatic struggles (…)”[9]

Palestine, Today

The global political, economic, social, and cultural context has changed dramatically since the Bandung Conference of 1955. The era of national liberation and Third-Worldism has waned. Much worse, the world is now plagued by the rise of populist authoritarianism, democratic backsliding, trampling of human rights and international law, erosion and collapse of institutions, greater concentration of corporate power, the crisis of multilateralism, and the climate emergency.

Today, while most of the world has been freed of direct colonial control, the legacy of settler-colonialism continues to impact the Global South and shape their political, economic, and social systems in profound ways. The merciless oppression of an entire population in Palestine and the Occupied Palestinian Territories remains unabated. The world order in which the Occupying Power Israel and its backers from the Global North are granted impunity for their war crimes endures. The international community has failed Palestine.

The trauma of genocide against the entire Palestinian people by Israel has reached new depths, and the root causes of the decades-long conflict and oppression: illegal occupation, apartheid, and the unchecked impunity of a settler-colonial state remain untouched. Human Rights and Social Justice Lecturer Ihab Shalbak (2023) describes this as the “project of worldmaking by dispossession of land and sovereignty. It is conceptualised as an embodiment and extension of the rule of law in a lawless world.”[10]

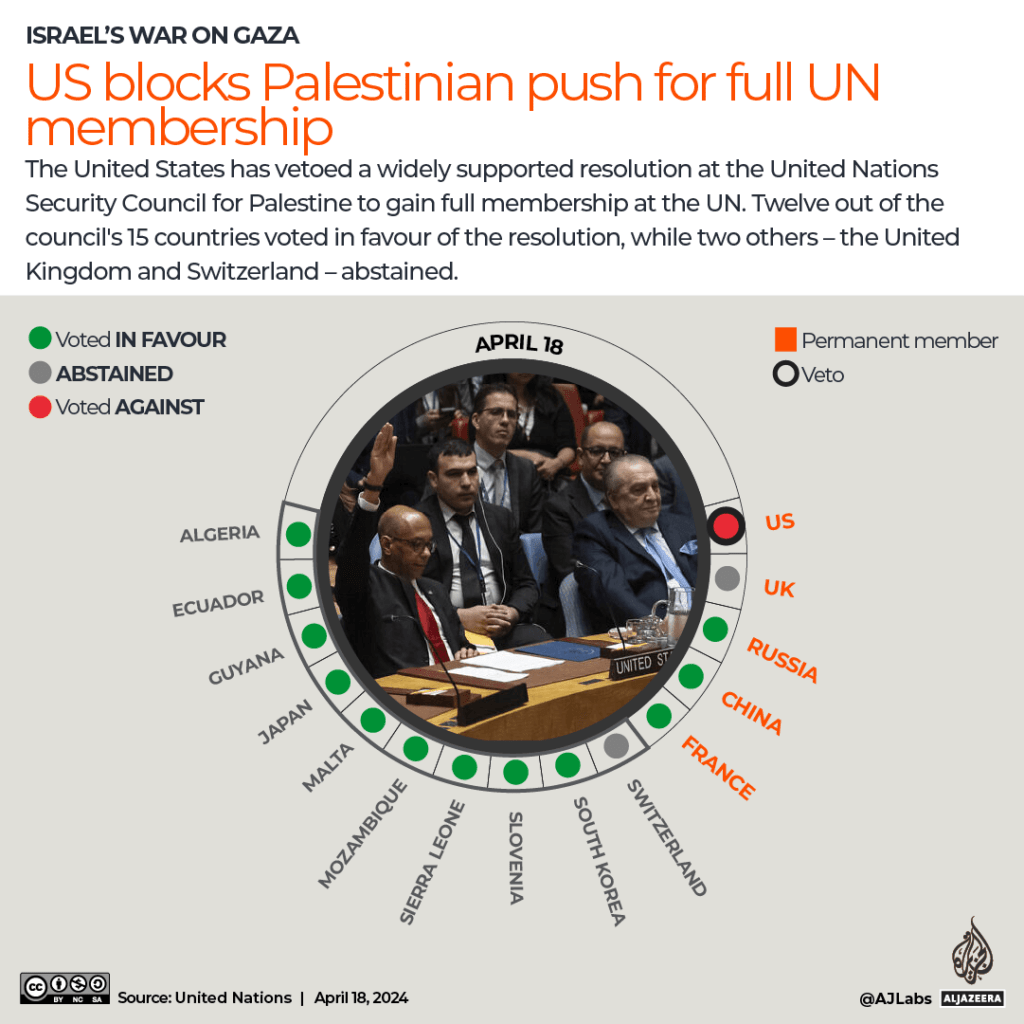

The US, sitting as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), uses its veto power against a resolution that would have paved the way for full UN membership for Palestine. 2024 April 18. Photo by Al Jazeera. Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/4/18/palestinian-bid-for-un-membership-set-for-security-council-vote, Creative Commons Attribution, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

It must be underscored that the dangers facing Palestine have intensified to unprecedented levels amidst the ongoing genocide: a brutal convergence of authoritarianism, corporate profiteering, and unbridled imperialist arrogance emboldened by the failure and explicit complicity of the international community. Legal scholars Noura Erakat and John Reynolds (2023) posit, “While processes of formal decolonization have since played out across most of the Global South — notwithstanding the inequalities and violence of the postcolonial state and the neocolonial order — Palestine remains a quintessential site of ongoing settler colonialism and apartheid.”[11]

At the time of writing, the Occupying Power Israel has waged a relentless genocidal and barbaric war on Palestine and the Occupied Palestinian Territories for 566 days. The UN Secretary-General António Guterres described the conditions for Palestinians in Gaza as ‘appalling and apocalyptic’ and repeatedly remarked how the situation in Palestine and the Occupied Palestinian Territories is growing more perilous by the day: “[I]n the occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, militarized Israeli security operations, settlement-expansion, evictions, demolitions, violence and threats of annexation are inflicting further pain and injustice.”[12]

Combined figures from the Ministry of Health (MoH) in Gaza and the Israeli authorities reveal the staggering human toll since October 7, 2023: at least 51,266 Palestinians and 1,608 Israelis—15,646 of whom were children—have been killed, and over 116,991 Palestinians and 8,012 Israelis injured as of April 22, 2025.[13] Thousands more remain buried beneath the rubble of their destroyed homes and temporary shelters.

The level of destruction is immense as reported in various reports by the UN Office for the Coordinated Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) and related agencies: 1.95 million people have been projected to face high levels of acute food insecurity; 91% of households have experienced water insecurity; 92% of housing units have been destroyed. Israel has also used an inhumane and internationally prohibited method of warfare, described by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food (UNSR on the RTF) Michael Fakhri as a “deliberate, international, structural, and long-lasting starvation campaign”—the fastest in modern history—waged against the Palestinian people.

While the scale of Israel’s ongoing violence is unprecedented, it must be understood as part of Israel’s broader settler-colonial project, its destruction of all means of life for the Palestinians, and the inherent logics of ‘erasure from the face of the earth’ that underpin it. In the words of Blinne Ní Ghrálaigh, member of the South African legal team at the International Court of Justice (ICJ): “This is the first genocide in history where its victims are broadcasting their own destruction in the desperate, so far, vain hope that the world might do something.”[14]

To capture the enormity of destruction and death Israel has inflicted against the Palestinian people, several words have been used: urbicide (killing of a city), scholasticide (total annihilation of education systems), domicide (widespread and systematic destruction of homes), ecocide (severe harm to nature), and holocide (the annihilation of an entire social and ecological fabric).

It must be emphasized that what the Occupying Power Israel is doing now did not happen in a vacuum and has its seeds in history.[15] The ongoing genocidal war against the entire Palestinian population—with massive and unqualified support from the United States, Germany, and former colonial powers France and Britain—must be contextualized against the historical backdrop of a decades-long regime of settler-colonialism, apartheid, dispossession, and ethnic cleansing.

And yet, even more important perhaps to combat the sense of collective numbness and despair, as well as the mainstream Western media’s systematic bias against Palestinians in their coverage of Palestine and Israel—the peoples’ struggles, solidarity, and resistance must be placed at the center of the counternarratives as springwells of hope.

Waves of Global South Solidarity

Despite the continuing legacy of depredations spawned by the economic and political domination by the Global North, the realities of the current world configuration, and the unabated genocide in Palestine and the Occupied Palestinian Territories, nothing has been able to stop the wave of anti-colonial solidarity with the Palestinian people. This solidarity involves actively opposing systems that enable violence against Palestinians, questioning political agendas, resisting colonial narratives, and prioritizing justice over other interests.

Collective actions and multi-pronged strategies by peoples’ organizations and movements from the Global South have been done. In 2024, the global petition, “From Bandung to Gaza” was launched with the view of building a united front against Israel’s regime of genocide and apartheid to “honor our shared past, empower our intersectional struggles in the present, and pave the way for a future rooted in freedom, justice, equality and dignity for all.”[16] It heeds the call of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) Movement on state and corporate perpetrators and colluders, which remains an essential tactic, drawing lessons from the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa.

Similarly, several waves of solidarity actions swept across continents: from the massive student encampments protesting their university’s complicity with Israel, the refusal of dock workers to offload ships carrying military cargo, coal, and fuel bound for Israel, to the principled actions taken by Global South states, cutting their diplomatic ties with Israel. South Africa, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Comoros, Djibouti, Chile, and Mexico have called on the International Criminal Court (ICC) to investigate war crimes committed by Israel in Gaza. This has led to the issuance of arrest warrants by the ICC against Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant. South Africa brought before the ICJ a genocide case against Israel, supported by several countries in the Global South.[17]

Table 1. Actions taken by Global South states against Israel following 2023 October 7, from various sources including news reports, official decrees, public statements, and declarations by heads of state, government, and foreign ministers.

| States | Actions Taken |

| Bahrain | Recalled its ambassador to Israel and suspended economic relations with Israel, citing a “solid and historical stance that supports the Palestinian cause and the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people.” |

| Belize | Suspended diplomatic ties with Israel and renewed its call for “an immediate ceasefire in Gaza, unimpeded access to humanitarian supplies into Gaza and the release of all hostages.” |

| Bolivia | Severed all diplomatic ties with Israel (previously cut in 2009 and reestablished in 2020) in response to Israel’s “aggressive and disproportionate” attacks on Gaza. |

| Brazil | Recalled its ambassador to Israel, with President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva publicly declaring: “What’s happening in the Gaza Strip isn’t a war, it’s a genocide.” |

| Chad | Recalled its chargé d’affaires to Israel and condemned “the loss of human lives of many innocent civilians” and called for a “ceasefire leading to a lasting solution to the Palestinian question.” |

| Chile | Recalled its ambassador to Israel for the “unacceptable violations of International Humanitarian Law that Israel has incurred in the Gaza Strip” and Israel’s “collective punishment of the Palestinian civilian population.” |

| Colombia | Recalled its ambassador to Israel, with President Gustavo Petro publicly declaring: “If Israel does not stop the massacre of the Palestinian people, we cannot be there.” Subsequently cut all its diplomatic ties with Israel, imposed a military embargo, and banned all coal exports to Israel. |

| Honduras | Recalled its ambassador to Israel in light of “the serious humanitarian situation the civilian Palestinian population is suffering in the Gaza Strip.” |

| Jordan | Recalled its ambassador to Israel for threatening regional security and the “unprecedented humanitarian catastrophe” created by Israel. |

| Malaysia | Banned Israel-flagged and Israel-bound cargo ships from docking at its ports for Israel’s continued violation of “international law through the ongoing massacre and brutality against Palestinians.” |

| Namibia | Denied port access to a German-owned vessel carrying military equipment to Israel, stating its “obligation not to support or be complicit in Israeli war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, as well as its unlawful occupation of Palestine.” |

| South Africa | Recalled its entire diplomatic mission in Israel for the “refusal of the Israeli government to respect international law” and its “genocidal airstrikes” against Palestinians; filed a genocide case against Israel at the ICJ. |

| Turkey | Recalled its ambassador to Israel citing its refusal to heed calls for a “ceasefire and continuous and unhindered flow of humanitarian aid,” suspended all trade with Israel, and initiated a joint letter to the UNSC—backed by 51 other states— “calling on all countries to stop the sale of arms and ammunition to Israel.” |

All of these actions have clearly demarcated the line on the question of Palestine between the Global North and the Global South.

The ICJ ruling, while non-self-executing, has provided crucial tools for organizing and mobilizing people—whether in national courts, in congressional halls, or on the streets—to further isolate Israel and actively pressure states to act decisively on their obligations, and hold them accountable for the double standards inherent in the positions they have taken.[18] With the ICJ case, South Africa, together with its Global South allies, has not only challenged the West’s moral high ground but also pushed debates on the legacy, sentiments, and politics of postcoloniality to a new scale and scope.

Anthropologists Julie Billaud and Antonio De Lauri (2024) emphasized not only the symbolic importance of the South Africa’s case but also the historic coming together of the Global South against settler colonialism, oppression, and apartheid, as what was envisioned in Bandung: “It is simultaneously exposing the historical roots that define the West’s unfailing support to Israel as an outpost serving the double objective of guaranteeing privileged access to natural resources in the Middle East while holding off ‘barbarians at the gate,’ to use a classic colonial trope.”[19] For its continued support and defense of Israel’s genocide of the Palestinian people, Germany received a strong rebuke from its former colony, Namibia, where it waged a colonial genocidal war against the Herero and Namaqua Indigenous peoples from 1904 to 1908.

While the ICJ case is symbolically powerful, international law—whose foundations are deeply intertwined with the legacy of colonialism—remains a site of complicity and contestation. It is only through grassroots pressure and actions that such victories can be translated into meaningful and tangible change for the Palestinian people. In the words of the South African BDS Coalition, following the ICJ ruling: “International law alone cannot bring us justice. Only our relentless mobilisation to build people power can ultimately end international state, corporate and institutional complicity in Israel’s 75-year-old regime of settler-colonialism and apartheid and thus support Palestinian liberation.”[20]

On January 31, 2025, various states signed on to the Hague Group convened by the international political organization, Progressive International (PI).[21] The Global South is spearheading this coordinated push for collective action through international law to ensure that Israel and its complicit backers from Europe and the US will be brought to justice.[22] With the twin imperatives of exposing the hypocrisy of the West, their lack of moral clarity, and double-standard use of human rights, alongside ending Israeli exceptionalism, settler-colonialism, and systemic impunity, the Global South takes on a critical role in the international arena for Palestine.

The formation of the Hague Group is not a guarantee that justice will be delivered. However, it provides an opening to galvanize international solidarity and political will to impose military and economic sanctions against Israel to end its genocide, apartheid system, and illegal occupation of Palestine. As the Algerian political writer and activist Hamza Hamouchene (2024) notes, “These developments strengthen the trend of a move towards a multi-polar world where the South asserts itself politically and economically. We are not yet in a new Bandung phase, but this historical juncture will accelerate the decline (at least ideologically) of the US-led empire and will intensify its contradictions.”[23]

All of the above marks a renewed spirit of unified defiance among peoples in the Global South, a spirit that is vital in the universal struggle to oppose the devastation wreaked on humanity by imperialism, colonialism, and their legacies.

Advancing the Spirit of Bandung and Beyond for Palestine

Bandung arose at a moment of anti-colonial consciousness and great Global South awakening. It provided an avenue to discuss and untangle the varied structural and systemic problems of the world, as well as possible political reconfigurations and alternative futures. It gave hope through cooperation, solidarity, and collective struggles against all forms of oppression and colonial violence.

However, it failed to adequately address the critical questions of varying political structures and diverse ideologies of the African and Asian states and their relations to the international political economy. As Political Science and International Relations Professor Tukumbi Lumumba-Kasongo posits, “Thus, although the symptoms of the problems were well defined, it did not sufficiently clarify what kinds of political societies to be created, based on what kinds of national ideologies, as a result of the declarations and final resolutions of the conference.”[24]

Moreover, to actualize the Bandung resolutions into the policy arena, the state system was firmly valorized, even as regional cooperation was encouraged and supported, and the principles articulating human dignity were promoted. Filipino scholar-activist Walden Bello (2025) argues that “Bandung, for all the positive contributions it made to decolonization, had the one questionable legacy of legitimizing the nation-state as the principal, if not the only, vehicle for developing relations among the post-colonial societies, to the detriment of other relations of South-South solidarity.”[25]

It has embraced a state-centric approach to the Palestinian question, accompanied by universalist legal rhetoric, with the UN and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)—limiting as they are—as the main points of reference, even as these emerged from the legal and political genealogies of the colonial powers. Thus, advancing the Spirit of Bandung involves democratizing the international political and legal system, including multilateral spaces such as the UN, and going beyond statist notions of politics, power, and social organization that only serve to maintain the status quo.

The world demands an end to Israel’s illegal occupation of Palestine, in a landslide UN vote. 2024 September 19. Photo by Ben Norton, Geopolitical Economy Report, retrieved from https://geopoliticaleconomy.com/2024/09/19/end-israel-occupation-palestine-un-vote/

Israel’s genocide in Gaza has ushered in a new age, at a moment where the world is confronting an era of multi-layered, interlocking, and deepening crises—of climate breakdown, wars and regional conflicts, economic instabilities and inequalities, geopolitical upheavals, democratic backsliding, and the rise of fascist and authoritarian regimes—all of which stand to reconfigure the future. At the same time, what is happening now in Palestine offers insight into how there remains an imperative to dismantle colonialism, and, concomitantly, into the inadequacy of the statist vocabularies of resistance inherited from the birth of the ‘anti-colonial storm’ that emerged in Bandung.

Indian historian and journalist Vijay Prashad (2007) chronicles how “Bandung is best remembered, among those who have any memory of it, as one of the milestones of the peace movement. Whatever the orientation of the states, they agreed that world peace required disarmament (…) The racist disregard for human life occasioned a long discussion at Bandung on disarmament. In the conference communique, the delegates argued that the Third World had to seize the reins of the horses of the apocalypse.”[26] This disarmament call needs to be reverberated ever strongly to present-day Palestine.

On October 16, 2023, Palestinian trade unions and professional associations issued a powerful call to international unions, urging them to ‘Stop Arming Israel’—characterizing the struggle for Palestinian justice and liberation as “a lever for the liberation of all dispossessed and exploited people of the world.”[27] This global appeal highlighted the vast scale of military and diplomatic support provided to Israel, particularly by the EU and the US, with the latter’s spending on Israel’s military operations in the region totaling at least a conservative estimate of $22.76 billion for just a year, according to the report, “Costs of War” by scholars from Brown University.[28]

Palestinian-American writer Tariq Kenney-Shawa (2025) asserts: “The rest of the world has an opportunity to fill the void left open by Washington’s abandonment of even the pretense of upholding international law. If the rules-based order is to mean anything — or perhaps if it is to finally mean something — other states must hold Israel accountable. This means fulfilling their obligations under international law, imposing economic sanctions, and enacting arms embargoes against Israel. Countries that have long deferred to U.S. leadership now have an opportunity to uphold the principles they claim to champion. Failing to do so will have consequences that no one is immune from.”[29]

Thus, the anti-colonial and right to self-determination and sovereignty mission of Bandung is unfinished. And it should apply as much to nation-states as to peoples and communities. There remains a need for radical analysis, community organizing, and collective visioning that centers convergences of anti-imperialist, anti-capitalist, decolonizing, feminist, and ecological resistances with a view to collectively (re)imagining and materializing emancipatory and radical futures—one that transcends the Spirit of Bandung for Palestine, and captures and redefines this Spirit towards genuine self-determination and transformations for all.

As former South African minister Ronnie Kasrils (2025) argues, “We need to rebuild something of the spirit of the time when the Third World was not just a geographical or economic category, but a political project rooted in anti-colonial struggles, aimed at creating a unified global bloc to challenge imperialism.”[30] Ending colonialism, in its modern dress, “wherever, whenever, however it appears” as declared by Sukarno in Bandung still rings true today. This would involve the dismantling of the neocolonial economic structure that remains deeply entrenched in Palestine and across the world.

Professor of Political Economy and Global Development Adam Hanieh (2024) adds how the question of Palestine must be located within the intersecting history of fossil capitalism in West Asia and the contemporary struggles for climate justice: “The extraordinary battle for survival waged by Palestinians today in the Gaza Strip represents the leading edge of the fight for the future of the planet.”[31] Thus, advancing the Bandung Spirit in the present context would also entail the dismantling of the apartheid war machine, the disruption of fossil fuel flows, and the undermining of the structures underpinning these two. It would also necessitate the centering of decolonization and self-determination struggles that confront the violence wrought by Israel upon Palestinians, not only with its ongoing genocide, but also with its decades-long illegal occupation of Palestine—violence manifesting in different forms, perpetrated by systems and structures of oppression.

As the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research asserts, “Until the peoples of the Global South are able to overcome some of these (and more) challenges, it is unlikely that the Bandung Spirit will be part of the actual movement of history. We are emerging slowly out of a defunct epoch of history, the epoch of imperialism. But we have not yet emerged into a new period that is beyond imperialism – the hardest of all structures from which to break.”[32]

Whither flow the rivulets?

Seventy years ago, Sukarno declared in Bandung, “Irresistible forces have swept the two continents. The mental, spiritual, and political face of the whole world has been changed, and the process is still not complete. There are new conditions, new concepts, new problems, new ideals abroad in the world. Hurricanes of national awakening and reawakening have swept over the land, shaking it, changing it, changing it for the better.”[33] Today, amidst the heightening contradictions of capitalism and imperialism in their contemporary guise, dismantling the political, economic, social, and cultural systems that continue to promote wretched hierarchies based on dispossession and domination of peoples and nature remains critical.

Therein lies the refusal to play by the rules set by the very powers that sustain and perpetrate such systems of oppression and violence, including the system that has allowed the genocide of Palestinians by the Occupying Power Israel to continue. In this extremely dangerous time, of a complex and turbulent world in which the old certainties no longer apply, communities and societies of mutual understanding and international solidarity must be strengthened, and one that is decolonial and whose spirit of resistance remains unyielding, no matter what, no matter how.

From Bandung to Palestine, countercurrent waves of unprecedented numbers converge across the world, in all continents, and continue to go against the vestiges of imperialism and the continued encroachments, extraction, exploitation, and occupation by colonial powers in Palestine and the rest of the Global South. As the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish imparts: “Each river has its own. Our land is not barren. Each land has its own rebirth. Each dawn has a date with revolution.”[34]

Thus, the birth and rebirths of Bandung and beyond, and its resolute, enduring Spirit for rights, justice, self-determination, liberation, and peace flow ever onward.

Endnote:

[1] Massad, J. (2024 April 4). Palestine at Bandung: How the historic Asian-African conference challenged imperialism. London, United Kingdom: Middle East Eye. Retrieved from https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/palestine-bandung-how-asian-african-conference-challenged-imperialism

[2] Final Communique of the Asian-African Conference of Bandung (1955 April 24). Asia-Africa Speaks from Bandung. Djakarta: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Indonesia. Bandung, Indonesia.

[3] Ampiah, K. (1997). The Dynamics of Japan’s Relations with Africa: South Africa, Tanzania and Nigeria (1st ed.). Routledge. pp. 39-40. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203440001

[4] Statement by the Egyptian Delegation at the Opening Session (1955 April 18), Asia-Africa Speak from Bandung. Djakarta: The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Indonesia, 1955. pp. 67-70.

[5] Final Communique of the Asian-African Conference of Bandung (1955 April 24). Asia-Africa Speaks from Bandung. Djakarta: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Indonesia. Bandung, Indonesia.

[6] Prashad, V. (2007). The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World. New York: The New Press. 32-33.

[7] Hodali, S. (2024 March 20). ‘A Bond of the Same Nature’: Cartographies of Affiliation in the Global South. Oxford, United Kingdom: Ebb Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ebb-magazine.com/essays/a-bond-of-the-same-nature

[8] The South Centre. (2015 May 15). Asian-African Summit Adopts 3 Documents. Vernier, Switzerland. Retrieved from https://www.southcentre.int/question/asian-african-summit-adopts-3-documents/

[9] Samour, N. (2017). Palestine at Bandung: The Longwinded Start of a Reimagined International Law. In L. Eslava, M. Fakhri, & V. Nesiah (Eds.), Bandung, Global History, and International Law: Critical Pasts and Pending Futures, 595–615. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316414880.038

[10] Shalbak, I. (2023). Human rights in Palestine: from self-determination to governance. Australian Journal of Human Rights, 29(3), 492–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/1323238X.2023.2291210

[11] Erakat, N., Reynolds, J., Esmeir, S., Falk, R., Imseis, A., Natarajan, U., … Shamas, D. (2023). Roundtable: Locating Palestine in Third World Approaches to International Law. Journal of Palestine Studies, 52(4), 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/0377919X.2023.2274777

[12] Guterres, A. (2024 December 2). Quoted in “If Palestinian Refugee Agency Ceases to Operate, Responsibility to Provide Services Rests Solely with Israel, Secretary-General Says at Cairo Conference.” Remarks delivered by Amina J. Mohammed, Deputy Secretary-General at the Ministerial Conference to Enhance the Humanitarian Response in Gaza. Cairo, Egypt. Retrieved from https://press.un.org/en/2024/sgsm22483.doc.htm

[13] Cumulative casualty data from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) as of 2025 April 22. Retrieved from https://www.ochaopt.org/content/reported-impact-snapshot-gaza-strip-22-april-2025

[14] Blinne Ní Ghrálaigh, (2024 January 11), quoted in “Irish lawyer tells Hague that Gaza is ‘first genocide in history’ being broadcast in ‘real-time’,” Dublin, Ireland: The Journal, Retrieved from https://www.thejournal.ie/irish-lawyer-blinne-ni-ghralaigh-south-africa-israel-case-6269404-Jan2024/

[15] Focus on the Global South. (2023 November 17). End the Siege of Gaza; Stop the Killing and Forced Displacement; Unconditional Ceasefire Now! Statement. Focus on Palestine. Retrieved from https://focusweb.org/end-the-siege-of-gaza-stop-the-killing-and-forced-displacement-unconditional-ceasefire-now/

[16] The petition is led by Global South Response and endorsed by various grassroots movements and civil society organizations across Asia, Africa and Latin America: https://actionnetwork.org/petitions/from-bandung-to-gaza-towards-a-global-south-unified-against-israels-regime-of-genocide-and-apartheid

[17] These include Turkey, Indonesia, Jordan, Brazil, Colombia, Bolivia, Pakistan, Namibia, the Maldives, Malaysia, Cuba, Mexico, Libya, Egypt, Nicaragua, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (made up of 57 members), and the Arab League (made up of 22 members).

[18] Focus on the Global South. (2024 February 19). Peace, Justice, and Self-determination for Palestine: Oppose Occupation, Apartheid, and Genocide; Ceasefire Now! Statement at the World Social Forum, Kathmandu, Nepal. Focus on Palestine. Retrieved from https://focusweb.org/peace-justice-and-self-determination-for-palestine-oppose-occupation-apartheid-and-genocide-ceasefire-now/

[19] Billaud, J., & De Lauri, A. (2024 September 23). Gaza, South Africa and the Return of the Third World: Toward a Postcolonial Humanism. Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development 15(2), 267-271. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/hum.2024.a953065.

[20] South African Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Coalition. (2024 January 26). Apartheid Israel is Officially on Trial for Genocide: SA BDS Coalition Statement on the ICJ Order. Retrieved from https://web.facebook.com/SABDSCoalition/posts/pfbid02SHziP818bPM2U9ErSYQBEm1hMKB5YvAGadVpFWvt8dT4yGs38xQb3qmespnGBr6Ml

[21] The Hague Group was initiated by the Global South states Belize, Bolivia, Colombia, Cuba, Honduras, Malaysia, Namibia, Senegal, and South Africa. https://thehaguegroup.org/

[22] Castillo, G.D.G. (2025 February 28). Peoples’ Victories: A Watershed of Radical Hopes. Focus on the Global South: Bangkok, Thailand. Retrieved from: https://focusweb.org/peoples-victories-a-watershed-of-radical-hopes/

[23] Hamouchene, H. (2024 November 28). Vietnam, Algeria, Palestine: Passing on the torch of the anti-colonial struggle. Palestine Liberation Series. Transnational Institute: Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Retrieved from https://www.tni.org/en/article/vietnam-algeria-palestine

[24] Lumumba-Kasongo, T. (2015 July 25). Rethinking the Bandung conference in an Era of ‘unipolar liberal globalization’ and movements toward a ‘multipolar politics’. Bandung: Journal of the Global South 2:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40728-014-0012-4

[25] Bello, W. (2025 March 13). The Long March from Bandung to the BRICS. Bangkok, Thailand: Focus on the Global South. Retrieved from https://focusweb.org/the-long-march-from-bandung-to-the-brics/

[26] Prashad, V. (2007). The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World. New York: The New Press. 41-42.

[27] Palestinian Trade Unions. (2023 October 16). An Urgent Call from Palestinian Trade Unions: End all Complicity, Stop Arming Israel. International Statement. Retrieved from https://progressive.international/wire/2023-10-16-an-urgent-call-from-palestinian-trade-unions-end-all-complicity-stop-arming-israel/en

[28] Bilmes, L., Hartung, W., and Semler, S. (2024 October 7). United States Spending on Israel’s Military Operations and Related U.S. Operations in the Region, October 7, 2023 – September 30, 2024. Costs of War Project. Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University, United States. Retrieved from https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2023/2024/Costs%20of%20War_US%20Support%20Since%20Oct%207%20FINAL%20v2.pdf

[29] Kenney-Shawa, T. (2025 January 29). A Ceasefire Is Not Enough: Resisting the next phase of ethnic cleansing in Gaza. New York, United States: The Baffler. Retrieved from https://thebaffler.com/latest/a-ceasefire-is-not-enough-kenney-shawa

[30] Kasrils, R. (2025 January 1). Palestinian Justice Won’t Wait for the West. London, United Kingdom: Tribune. Retrieved from https://tribunemag.co.uk/2025/01/palestinian-justice-wont-wait-for-the-west/

[31] Hanieh, A. (2024 June 13). Framing Palestine. Palestine Liberation Series. Transnational Institute: Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Retrieved from https://www.tni.org/en/article/framing-palestine

[32] Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. (2025 April 8). The Bandung Spirit. Dossier No. 87. Retrieved from https://thetricontinental.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/20250324_D87_EN_Web.pdf

[33] Opening address given by Sukarno (1955 April 18), Asia-Africa Speak from Bandung. Djakarta: The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Indonesia, 1955. pp. 67-70.

[34] Mahmoud Darwish, “On Hope,” translated by Naseer Aruri and Edmund Ghareeb, in Enemy of the Sun: Poetry of Palestinian Resistance, 1970.

![[Press Release] There can be no justifications for land grabbing!” social movements and CSOs tell World Bank, UN agencies and governments](https://focusweb.org/wp-content/themes/Extra/images/post-format-thumb-text.svg)