“The development of this road linkage infrastructure will effectively generate economic and social benefits for both counties and will also create a positive impact to the DSEZ Initial Phase project development and the betterment of the well-being and livelihood of the population in DSEZ and the surrounding areas of both countries.” (Italian-Thai Development Public Company Limited’s 2018 annual report)

“Since the company cut through my farm with the road, environment and natural resources surrounding my village were impacted. I could no longer use water and get fish from the river nearby as it already dried out as a result of the road construction. Also, I could not easily collect food and vegetables from the forest. Now I normally rely on food at markets in other villages and motorcycle food carts”

On the bumpy and dusty road connecting Kanchanaburi in Thailand with Myanmar’s Dawei District, travelers are constantly reminded of the Dawei Special Economic Zone (SEZ), a large-scale development project of the Thailand and Myanmar governments, to be implemented by the Italian-Thai Development Public Company Limited (ITD).

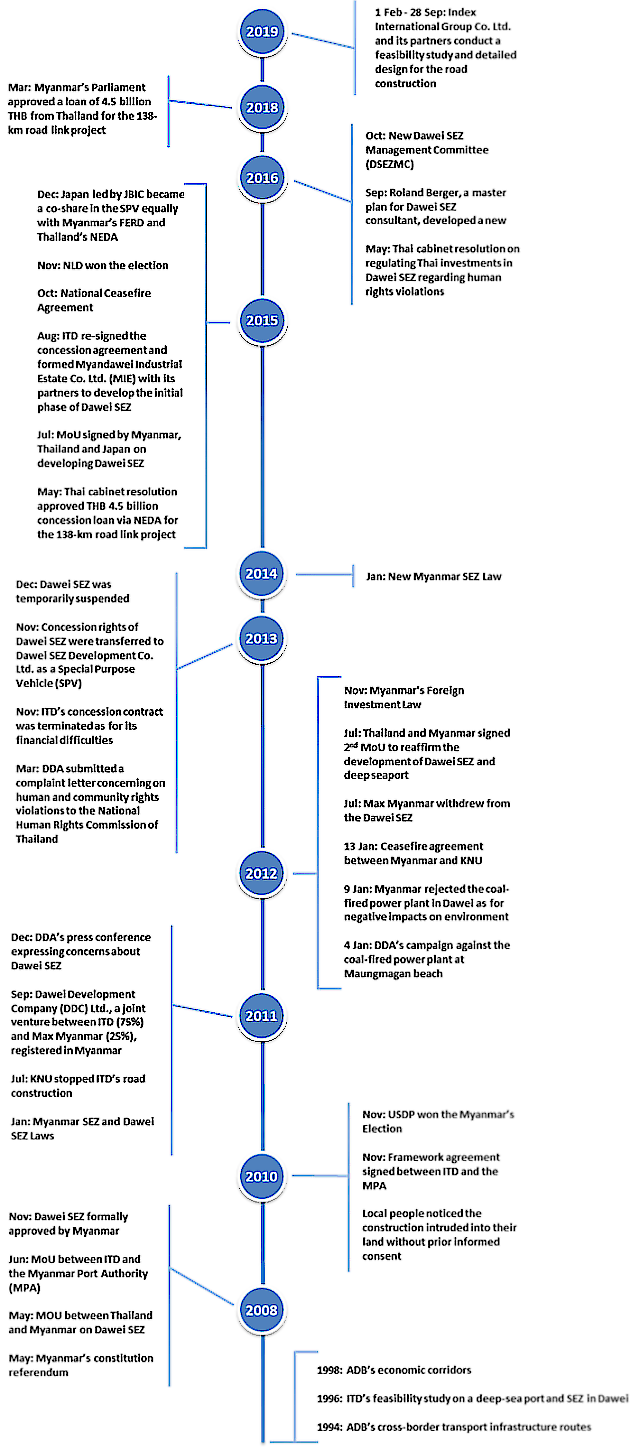

After a period of stagnation from the project’s official beginning in 2008 (see timeline at the end of this , ITD and its partners were permitted in 2015 by the Dawei SEZ Management Committee (DSEZMC) to develop a 27 square-kilometer initial phase. This is a small portion of the original 196.5 sq-km land area allotted for the project.[ii] As part of the initial phase, a two-lane road link project stretching 138 kilometers from Htee Khee border area to the Dawei SEZ will be built.

The dusty road connects Dawei SEZ through Myitta village to the Thai border at Htee Khee checkpoint (Supatsak Pobsuk, April 2019)

The road link will be expanded soon after Myanmar accepted in March 2018 a THB 4.5 billion (USD 144 million) loan through Thailand’s National Economic and Development Cooperation Agency (NEDA). By May 2018, both governments agreed to contract consultants to conduct a feasibility study and detailed design for the road construction. The feasibility assessment started on 1 February 2019 and is expected to finish by 29 September this year.

The construction of the road is expected to trigger the national and transnational movement of people, goods and investments to increase economic connectivity and integration in the region. The road is part of a sub-corridor of the Southern Economic Corridor (SEC) of the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Economic Corridors[iii], a highway network linking Dawei (Myanmar) with Bangkok (Thailand), Phnom Penh (Cambodia), Ho Chi Minh City and Vang Tau (Vietnam). It will serve as a supply link with Thailand’s Eastern Seaboard, and westward as a strategic gateway to South Asia, the Middle East, Europe and Africa.

The Greater Mekong Subregion’s Southern Economic Corridor. (Source Myandawei Industrial Estate)

Within Myanmar, the government hopes that infrastructure improvement will facilitate national and international investors to exploit and extract abundant natural resources, including fish, seafood, timber, rubber, palm oil, mines (manganese, iron, tin, tungsten and antimony), and offshore natural gas reserves in the Tanintharyi Region to feed covetous global markets.

The story so far of the Dawei SEZ illustrates interconnected and conflicting agendas of different actors, including Thai and Myanmar governments, the Karen National Union (KNU), investors, and local people.

The Other Side of Economic Connectivity and Interests

“The government was striving toward equal development of states and regions and spoke of the requirement for the project works to be completed on time to full standard, the need for the Region government to prevent waste of funds…Stability and peace could only be achieved when regions develop…” (Myanmar President U Win Myint during his visit to the road link project site on 7 May 2019)[iv]

In the Dawei SEZ, the region’s ancestral lands, commons and other natural resources that have sustained local peoples for generations will become commodities to feed economic growth of the country. The Myanmar Government claims these as national assets legitimized by special institutional and legal frameworks, in this case the 2012 Foreign Investment Law, the 2014 Myanmar SEZs Law, the 2018 amended Vacant, Fallow and Virgin Land Management Law (VFV Law), and the SEZ Management Committees, among others. Land grabbing, forced evictions and human rights violations have been widespread. A 2014 report of the Dawei Development Association (DDA), which supports affected villagers, estimated that approximately 22,000 to 43,000 people (between 4,400 to 7,800 households) from 20-36 villages will be affected by the SEZ and related projects, including industrial estates, deep sea ports, road-links, reservoirs and resettlement sites.[v]

Dawei SEZ proponents push the usual development myths of job opportunities, enhanced standards of living, improved infrastructures and better public facilities as benefits for local people. They also promise that those affected by the development project would receive adequate compensation and houses at suitable resettlement sites. Even though the ITD promotes its responsibility towards its investment through media, the realities on the ground showed its different side. Cha Khan Village is a good example.

“We’re on the same side as the villagers. We have to do everything to let them know that we’re their friends….The construction will happen for certain because it is the Myanmar government’s policy. But how will we be their friends and communicate what they want from the government and the project development?” (Mr. Terapong Techasatian, manager of ITD’s Corporate Social Responsibility program, 2013)

The former village of Cha Khan located at Nabule area, Yebyu Township illustrates how communities and their livelihoods fell apart because of the Dawei SEZ project. Living in the area for a century, Cha Khan villagers sustained their livelihoods by fisheries and salt farming. However, the Myanmar government confiscated coastal land for the ambitious deep seaport project of the Dawei SEZ. In 2013, the government arbitrarily confiscated the land confiscation and prohibited villagers from fishing in the sea. Some 30 villagers in Cha Khan Village were forcibly evicted by local authorities. All houses in the village were dismantled coercively by the construction contractor of the Dawei SEZ project.[vii] Some villagers were prosecuted and imprisoned for disobeying the evacuation order enforced by the authorities. Now, Cha Khan Village has disappeared and the area is uninhabited, awaiting the construction of the deep seaport. Villagers who used to live there were displaced forcibly elsewhere.

Only one family from Cha Khan Village resides among the 480 houses in the Bawah resettlement site which was built to accommodate affected people. However, the remaining 479 houses are unoccupied, and lacking electricity and water as promised. The family received one million Kyat (approximately USD 6,530) as compensation.

A row of empty houses at the desolate Bawah relocation site (Supatsak Pobsuk, April 2019)

Before resettling, the project also promised to provide vocational training and job opportunities in the project area for the affected people. However, the families have not seen any training or job opportunities since they relocated in March 2013. Since then, they had changed their livelihood from fishing to growing and selling vegetables because they no longer have their fishing equipment and find it difficult to access the sea. A family member in the Bawah resettlement site told her story:

“I was informed by authorities to move out of my village three days in advance. After I moved here (at Bawah relocation site), I realized that no one visited my family to follow up how we adapted ourselves to the new location…, Water and electricity promised by the company at the relocation site only lasted for four months, then no one asked after. Instead, we use lamps and carry water from a well. Now, I am fine to live here but my livelihood has changed as we eke out a living by growing and selling vegetables…I still hope that the (Dawei SEZ) project can be resumed as it may benefit us to some extent.” (Interview, 28 April 2019)

The ambitious project has not only dispossessed people of their lands, common properties and other natural resources, as well as depriving them of their means of subsistence, it has also excluded them as “unwanted people” from project benefits.

Development for Peace

The Dawei SEZ and the road link project are also part of the state-making process and aims to bring the central power of the Myanmar government into ethnic-controlled areas, to re-territorialize, and eventually centralize resources and improve population management. [viii]

From its heyday as the largest armed ethnic organization, the power of the Karen National Union (KNU) has declined considerably because of military challenges, political transformation, and economic development at the Thailand-Myanmar border. In the project region, the KNU’s 4th Brigade is based in Myeik-Dawei (Mergui-Tavoy) District and dominates 80% of the area where the road is being built. Since the mid-1990s, the 4th Brigade lost its influence after being unable to resist the power of Myanmar military and international investors, who jointly exploited natural gas and built a gas pipeline in southern Karen State.[ix]

The KNU signed a bilateral ceasefire agreement in 2012 and later the National Ceasefire Agreement in 2015. Before the ceasefire, the Dawei SEZ project intruded into KNU-controlled areas without notice. For the Myanmar government, the project is a tool to rule KNU areas. In July 2011, the KNU stopped road works after Karen communities complained the construction demolished their lands.[x] These days, the KNU’s sway can still be felt through KNU checkpoints along the road link project. At the time of the author’s visit in April 2019, KNU demands a THB 100 (USD 3.14) toll from passengers in order to pass through its several checkpoints. With this existing situation, the KNU continues as a quasi-government exercising parallel administration of the area.

The KNU issued a statement[xi] on 1 February 2018 on the resumed construction of the road link. While acknowledging in principle that the road will benefit local people, the KNU wanted the project to protect the security, cultures and environment of the ethnic communities. In addition, the KNU called on the Myanmar, Thai and Japanese governments to conduct a comprehensive environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) in accordance with Myanmar laws, the KNU’s land and forestry policies, and international standards. Prior to the construction, the KNU asked to be inclusively engaged in the negotiations to ensure sustainable development for local communities and for sharing revenues equally between the central and local governments. Moreover, they requested that the road construction comply with the principle of free, prior and informed consent (FPIC), including fair compensation for those who might lose their land and livelihoods. Finally, they said that the environment conservation plan and development should be in place so that the road construction will prevent and minimize impacts on environment and natural resources.

“Without a ceasefire, peace and political solutions, the road could not be built. However, the road should be a good development that brings sustainability, peace, political solutions and benefits to local people…if the project starts without political solutions, the project may not be sustainable…KNU sees that development and the peace process should go in parallel, not development first and peace later…we need to talk about investment, development, local people, environmental management plan, and KNU should be included as a stakeholder. In terms of benefits, KNU can use them to the organization and help local villagers in those areas on education, health and other livelihood support.” (The KNU’s Secretary in Myeik-Dawei District, interview, 26 April 2019)

The development of the Dawei SEZ can be also explained by the concept of “ceasefire capitalism”[xii] where transnational business corporations, the Myanmar government and some ethnic political elites have collaborated to reset the political-economy in ethnic-controlled areas after the ceasefire agreement. In this case, the Myanmar government will be able to expand and exercise its power in the KNU-controlled areas through infrastructure development and large-scale investment under the Dawei SEZ. In the context of widespread conflicts and developments in this region, local people have long suffered from being deprived of their rights to land and livelihoods. Whether development-for-peace or peace-for-development should come first, the rights and benefits of local people should be prioritized by all actors.

Civil Resistance amidst a State of Uncertainty

“Road is one good development and people will gain benefits from the road. However, development should involve all actors, especially affected communities, in the decision-making processes, which will make the project benefit everyone, not just one particular group.” (A villager from Kalit Gyi village that affected by the road construction, interview, 17 April 2019)

The Dawei SEZ illustrates how a top-down development approach has resulted in disastrous effects on local communities since the project has ignored the local participation in decision-making. The fate of pocal people’s lives, land and resources were planned from afar using political and economic maps, and enforced by the Myanmar government favoring economic development activities. Even though many people were already dispossessed and displaced, there are many who stood up to draw their own maps and community visions to counter top-down development.

Representatives of communities affected by the road construction raise their concerns on the impacts of the project (Supatsak Pobsuk, April 2019)

Local resistance against the Dawei SEZ project can be seen through different community tactics and strategies. The resistance started as soon as construction vehicles began destroying local peoples’ farmlands, crops and commons. The Tha Byu Chanung and Kalit Gyi villages are two out of at least 35 villages affected by the road link project.[xiii] Affected villages formed the Community Sustainable Livelihoods and Development (CSLD) to represent the voices of local villagers against the project. Affected local people expressed their grievance by blocking the road in 2012 and 2013 to deter the ITD and to request negotiations regarding compensation from land grabbing.[xiv] CSLD holds a monthly meeting and shares information related to the Dawei SEZ and its related projects. They also strengthen their network by collaborating with civil society organizations (CSOs) in the Tanintharyi Region, Thailand and international networks. They have issued and filed statements expressing their concerns over the impacts of the Dawei SEZ project, requesting the project to proceed in accordance to existing legislation as well as good practices.

“Dawei SEZ project is a warning sign, and a call for all community members to protect our community and resources…people have increased their engagement in safeguarding the community.” (The abbot of Ka Lone Htar Buddhist Monastery, interview, 27 April 2019)

In addition to the formation of a protection network, local communities have put forward alternative development proposals challenging the Dawei SEZ project. Their proposal pays particular attention to communities and their natural resources, putting people at the centre of development and emphasizing their right to self-determination. Ka Lone Htar village is one of the strong communities that has undertaken a number of alternative development activities opposing a reservoir project on Talaing Yar River which would supply water to fulfill projected demand from industrial estates in Dawei SEZ. The dam will submerge Ka Lone Htar village and community farms, and villagers would be relocated. Apart from staging protests as civil disobedience, villagers initiated community-based tourism and community forestry as resistance tools based on a community-led development approach. Their community-based eco-tourism introduces visitors to traditional livelihoods and provides to natural resources as a way of making people aware of their struggle. Likewise, community forestry aims to create protected forest areas while proposing alternative ways to manage natural resources.

Amidst a state of uncertainty, local communities show their readiness by forming networks, initiating alternatives as well as leveraging other means to counter the development being imposed on them. Local people have demonstrated that they are active citizens who know what they want and how to pursue their own path of development.

Towards Responsible and Accountable Development

“It does not matter where investment came from, but it should be transparent and accountable while communities should have right to know what and how development impacts them in short, medium, and long-term.” (A villager from Tha byu Chaung village that affected by the road construction, interview, 17 April 2019)

The Dawei SEZ and its related projects must not be seen as inevitable development. On the contrary, these projects exemplify the failure of the large-scale investment model in terms of responsibility and accountability for its impact. Protective structures and measures, including a legal framework and institutions in Myanmar do exist, but are inadequate to protect local people from negative impacts of the SEZ, as well as in reconciling large scale economic development. The Dawei SEZ is the result of the Myanmar government’s investment-friendly policies, legislative frameworks and structures created solely to pursue its political and economic interests.

Nonetheless, project actors, including government agencies, business corporations and banks should not only comply with social and environmental standards according to Myanmar laws but also with their state’s extra-territorial obligations on human rights and environmental protection. As transnational investors, they are obliged to conduct social, environmental and health impact assessments and share the findings with all concerned actors to open feedback opportunities prior to the project implementation. Moreover, effective grievance mechanisms and remedy should be available for those adversely affected. In this way, foreign investments in Myanmar can be seen as demonstrations of responsible and accountable investment.

Importantly, local communities must have the right to participate and make decisions on any development project which may affect their livelihoods and resources. They must also have rights to propose alternatives to development that balances local needs with national development agenda.

“Development by the government demands local communities to make sacrifices in favour of national interests. They said social and economic benefits will trickle down to locals. However, development should start and be fulfilled at the local level where social and economic benefits of local people will strengthen the whole nation’s interests” (The abbot of Ka Lone Htar Buddhist Monastery, interview, 27 April 2019)

—

[Acknowledgement: This article is part of the field-reporting project conducted between 26 April and 1 May 2019, supported by the Earth Journalism Network under Internews, the Thai Society of Environmental Journalists, and the Thai Journalists Association.]

[i]https://www.itd.co.th/document-file/ir/1919919696-AR-ITD-English-2018.pdf, accessed on 8 May 2019

[ii] According to the new master plan of the Dawei SEZ, the project will be split into two phases: 1) The initial phase (2015-2025) includes two-lane road, labour intensive industries, small port, a 27 sq-km industrial estate, temporary power plant and boil-off gas power plant, small water reservoirs, telecommunications landline, initial township and LNG terminal, and; 2) The second phase (2025-2045) includes heavy industries such as oil refinery, plastics, steel and fertilizer plants, and automobile assembly, (Source: Focus on the Global South (2017) SEZs and Value Extraction from the Mekong and 2017 Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia’s Progress Survey Report.

[iii] The three GMS Economic Corridors include the North–South Economic Corridor (NSEC), the East–West Economic Corridor (EWEC) and the southern Economic Corridor (SEC).

[iv] “President meets Taninthayi Region administrative, legislative, judiciary officials” from http://www.president-office.gov.mm/en/?q=briefing-room/news/2019/05/07/id-9365, accessed on 26 May 2019

[v]Dawei Development Association (2014) Voices from the Ground: Concerns Over the Dawei Special Economic Zone and Related Projects.

[vi]“The human side of a megaproject” from https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/news/341146/the-human-side-of-at, accessed on 26 May 2019

[vii]“Despite compensation, Cha Khan villagers find it hard to make a living” from http://karennews.org/2013/02/despite-compensation-cha-khan-villagers-find-it-hard-to-make-a-living/, accessed on 7 May 2019

[viii]Thabchumpon, Naruemon, et.al. (2015) Cross-border Economic Development, Human Security and Peace Building Process in Myanmar: A case Study of the Dawei Roadlink Project in Tanintharyi Division.

[ix] David Brenner (2018) Inside the Karen Insurgency: Explaining Conflict and Conciliation in Myanmar’s Changing Borderlands, Asian Security, 14:2, 83-99, DOI: 10.1080/14799855.2017.1293657

[x]Ibid, Dawei Development Association

[xi]“Karen National Union Statement on the Building of a Two-Lane Highway Connecting Dawei Special Economic Zone and the Thai Border” from http://www.knuhq.org/eng/public/pdf/knu5c7f8ee20481a20180201_Karen%20National%20Union%20Statement%20on%20the%20Building%20of%20a%20Two-Lane%20Highway%20Connecting%20Dawei%20Special%20Economic%20Zone%20and%20the%20Thai%20Border%20(eng).pdf

[xii]Kevin Woods (2011) Ceasefire capitalism: military–private partnerships, resource concessions and military–state building in the Burma–China borderlands, The Journal of Peasant Studies, 38:4, 747-770, DOI: 10.1080/03066150.2011.607699

[xiii]Paung Ku and Transnational Institute (2012) Land Grapping in Dawei (MyanmarIBurma): a (Inter)National Human Rights Concern

[xiv]Ibid, Dawei Development Association

![[Event] Forum and Book Launch of “Transitions”](https://focusweb.org/wp-content/themes/Extra/images/post-format-thumb-text.svg)