Across the globe, peoples and communities continue to reel from the impacts of multiple crises—rising costs of food, increasing hunger and food insecurity, deepening inequalities, worsening climate crisis, escalating conflicts and wars, and the intensifying use of repression and violence in the name of profit and wealth accumulation.

In the Philippines, while different factions of the political elite fight over power and control—jockeying for key posts, securing economic deals for their own benefit, pushing for self-serving policy proposals—their mainstream responses to these crises fail to address the structural roots and only serve to perpetuate a corporate-driven development model.

Meanwhile, in Latin America, the left is facing a crisis of legitimacy. During the periods in which the left was in power, it was captured by the capitalist and extractivist agenda that has perpetually destroyed the environment, undermined peoples’ access to resources, and thereby aggravated economic inequalities. As such, there is an urgent need for the Latin American left to reinvent itself in order to regain its legitimacy.

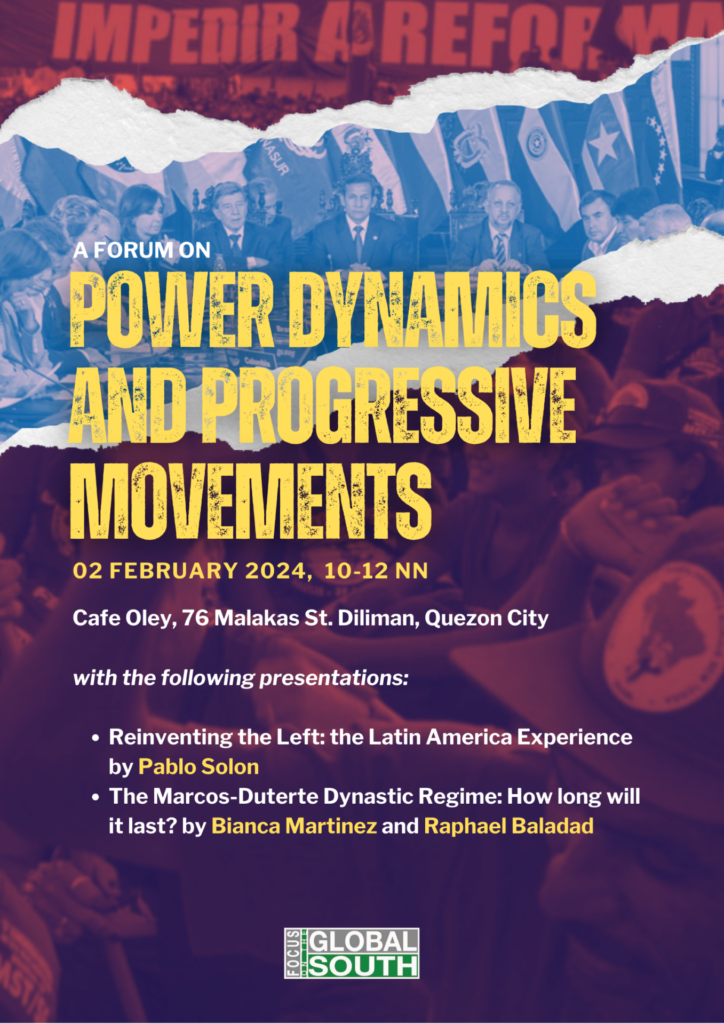

In this context, Focus on the Global South Philippines organized a forum on Power Dynamics and Progressive Movements last February 2, 2024. Presentations were made by Focus staff Raphael Baladad and Bianca Martinez as well as Pablo Solon—director of Fundación Solón, former executive director of Focus on the Global South, and former Ambassador of Bolivia to the UN. Bianca and Raphael’s presentation focused on the rift between the ruling Marcos and Duterte dynasties and its implications on the Philippine political landscape, especially with the upcoming 2025 elections. Meanwhile, Pablo focused on some of the circumstantial and principal errors committed by the Latin American left and how these have contributed to the emergence of the extreme right. Towards the end of the forum, participants reflected on key lessons that Philippine progressive movements could learn from the experience of the left in Latin America as the former is presented with a critical opportunity to challenge dynastic and elite politics and to make strides towards a truly democratic governance system from below. This event report summarizes the key points that came out of the forum.

An opportunity for the left in the Philippines

In the Philippines, the Marcoses and Dutertes—two of the most powerful dynasties that brokered an electoral alliance in 2022—are now embroiled in a power struggle. On the one hand, the Marcoses have harnessed their political capital to tighten their grip on Congress and form “supermajority” blocs. With their control over the supermajority, they were able to launch an all-out offensive against the Dutertes. The allies of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. have exposed and investigated Vice President Sara Duterte’s questionable use of confidential funds, ousted the Dutertes’ allies from the House leadership, threatened to cooperate with the International Criminal Court in investigating the human rights violations under the drug war of former President Rodrigo Duterte, and resumed peace talks with communist rebels, thereby undermining Duterte’s violent anti-insurgency campaign that was hinged on the indiscriminate political repression and persecution of progressive movements. The success of the Marcos-led offensive can be seen in the mass defection of politicians from Duterte’s political party towards that of Marcos, thereby further consolidating the Marcoses’ political capital.

Given the vast influence that Marcos and his allies now wield especially in the House of Representatives, they are now pushing for Charter Change to amend or possibly even revise the constitution. While the pretext used by proponents of Charter Change is to liberalize economic provisions in the constitution, this is simply used as a veil to conceal the true political motives behind Charter change—that is, either to push for term extensions or to institutionalize a unicameral parliamentary form of government. There are allegations that House Speaker Romualdez—cousin of President Marcos—has a personal stake in pushing for a parliamentary form of government in order to pave the way for him to become Prime Minister.

Despite this, however, Sara has remained more popular than Marcos. Knowing the extent of her influence, she has tactically used her mass support base to rally against Marcos and his allies. For instance, when the Marcos government decided to resume the peace talks with communist rebels, she stingingly described it as an “agreement with the devil,” tapping into the deep-seated anti-communist sentiments of many Filipinos.

The elites’ preoccupation with politicking while majority of Filipinos suffer from the economic and climate crisis has served to undermine the establishment’s legitimacy. With the Marcoses and Dutertes engaging in mudslinging and the liberal democrats having lost their legitimacy owing to the anti-liberal sentiments fomented by the Dutertes, the left and progressive movements are thus presented with a critical opportunity to challenge dynastic politics and to advance an alternative development agenda grounded on human rights and social justice.

However, one challenge for progressives is the Dutertes possibly projecting themselves as the “new opposition” to the Marcoses. As early as now, each side is already co-opting elements of the human rights and social justice agenda and weaponizing these against their political rival. For instance, the Marcoses are using the ICC investigation into the drug war as leverage against the Dutertes, thereby reducing it as a tool for politicking. These political theatrics erase the trauma, poverty, and instability caused by the drug war on communities and families of victims as well as the need to exact accountability from those who designed and operationalized the drug war.

On the other hand, the Department of Education under the leadership of Sara Duterte “encouraged” public schools across the country to hold commemorative activities in honor of the 1986 People Power Revolution that restored democracy and ousted Ferdinand Marcos Sr., the late dictator and father of the current President Marcos. However, this pro-democracy stance of Sara Duterte is nothing but smokescreen. It was not long ago when the Dutertes supported the massive disinformation campaign that helped whitewash the Marcos dictatorship, while vilifying the legacy of activists who fought hard to defend democracy during the time of Marcos. The Dutertes have also been at the forefront of eroding democratic institutions, systematically violating human rights, and persecuting human rights defenders especially during the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte.

In this context, the key challenge for progressive movements is how they will distinguish themselves and their narratives amid the political infighting of the elites and defend the human rights and social justice agenda from cooptation.

The crisis of the left in Latin America

On the other side of the world, in Latin America, the political landscape has constantly shifted, with the seat of power rotating between the left and the right-wing. However, with the passing of each political cycle, the pendulum has been swinging more strongly towards the right. The Latin American left is facing a crisis of legitimacy for a number of reasons, and this has provided more opportunities for the right-wing to reclaim and cement their hold on power.

The first “pink tide” or turn towards left-leaning governments in Latin America came as a reaction to the negative impacts of neoliberal policies introduced in the 90s, which left several countries in the region with high levels of unemployment, inflation, and rising social inequality. During its first wave, pink tide governments sought to institutionalize a welfare state. They implemented initiatives that mitigated the impacts of neoliberal policies such as by increasing wages, increasing public subsidies in essential services, and offering conditional cash transfers to marginalized populations. The initial results of the welfare policies implemented by the first pink tide governments included a decline in income inequality, unemployment, extreme poverty, malnutrition, and hunger.

However, the welfare state was largely underpinned by the rise of various commodity prices in the early 2000s owing to the rising demands from emerging markets. To take advantage of increasing demand, pink tide governments increased commodity trade with these emerging markets, most especially China. Given the increasing demand and prices of metals, chemicals, and fuels, other Latin American governments also ramped up mineral resource extraction, thereby degrading the environment, hampering land reform, undermining people’s access to resources, and worsening inequality.

But as commodity prices began to decline in 2010, Latin American governments that became dependent on it saw a decline in public revenues, thereby eroding the very foundation of their welfare policies. Supporters thus became disenchanted, eventually leading to the decline in popularity of left-leaning governments and the embrace of the right-wing.

Despite there being a resurgence of the pink tide in the late 2010s and the early 2020s, this is smaller in scale, less radical, and does not have as deep of a mass base as compared to the initial pink tide. At the same time, the wave of conservatism in other parts of Latin America continues, such as in the case of Argentina which, for the first time in the country’s history, elected a far-right neoliberal candidate, Javier Milei, as president during the 2023 elections. In Ecuador, many people have supported increased militarization and the intervention of the US military in order to restore peace and order amid the ongoing narco gang violence.

The conservative wave in Latin America and the dilution of the pink tide can largely be attributed to the left’s failure to make significant changes in the economy, to move away from extractivism, and to pursue radical land reform. At best, it institutionalized a welfare state that still largely relied on the volatile dynamics of global capitalism. Another big mistake committed by the left is that when left-leaning leaders came to power, social movements became complacent, less autonomous, more dependent on the state, and, in some cases, even corrupted by power. Grassroots organizing also declined, thereby weakening the left’s critically conscious mass base.

Lessons from Latin America to the Philippines

While seemingly different at first, the political contexts of the Philippines and Latin America in fact complement each other. The Philippines has never had a progressive leader, yet it is now presented with an opportunity to challenge elite rule and make headway towards grassroots democracy as the political contest between major dynasties intensifies. In this pursuit, Philippine progressive movements stand to learn lessons from the Latin American experience, which has seen the left rise to power but also unfortunately lose its legitimacy owing to some of the strategic mistakes it made along the way. Below are some of the key lessons that came out from the discussion among the forum presenters and participants:

- The left in the Philippines has been fixated on gaining influence at the national level. Meanwhile, local politics continue to be dominated by clans. Dynastic politics take root at the village level, where local politicians serve as power brokers for provincial, regional, and national political clans. As such, progressive movements must consider seriously contesting local politics and elections if it hopes to challenge dynastic politics at the national scale.

- While it is necessary for progressives to gain seats in government by winning the elections, it must be done with cautiousness. The experience of the Latin American left has clearly shown that the seat of power can corrupt more than it can serve as a vehicle for meaningful systemic change. In order to mitigate this, mechanisms for accountability and “counter-power” from social movements must be institutionalized. And for these mechanisms to be effective, movements must remain autonomous and independent—not just against the state but also within the left. Social movements should not be blinded by the notion that electoral victory is the be-all-end-all of advancing the progressive agenda. Rather, it should be regarded as one strategy complemented by many others.

- Social movements should not be reduced into a mere vehicle for power. Rather, they should serve as the means to ensure that representatives in government follow the will of the people. Any progressive government that comes to power must thus necessarily ensure that the integrity of people’s direct participation in governance—not just through their representatives—is maintained and protected.

- It is of paramount importance for progressive movements both in the Philippines and Latin America to reinvigorate grassroots organizing, build a critical mass base, and generate social pressure from below. Political parties—no matter how progressive their principles are—will not be enough if they have no critical mass base.

- For any progressive movement that will come to power, it is inevitable (and at times even necessary) that they will negotiate or bargain with other forces that they are not politically aligned with. When it comes to negotiating with other countries, governments led by progressives or by the left should be careful not to fall into the trap of “camp thinking,” which fosters group-based identities that in turn lead to exclusionary politics. This means that they should not refrain from criticizing other countries that are politically aligned with them or that also embrace anti-imperialist sentiments. Meanwhile, when it comes to national politics, the necessity of elite bargains is a bit more complex. There are times when the formation of broad coalitions and strategic compromises are necessary in order to prevent political and economic crises from going further downhill. In the case of Brazil, for example, Lula had to forge alliances with the radical left and even right-wing neoliberal forces in order to win against Bolsonaro. At the time, this was viewed by many as strategic because it was crucial for Brazil to prevent Bolsonaro from further destroying the Amazon, rolling back protections for indigenous peoples, and intensifying neoliberal and pro-market policies. But while broad coalitions can at times be necessary to ward off bigger evils, progressive social movements that support these formations also need to be honest with themselves in addressing the deep contradictions that will inevitably emerge from negotiations and bargains with different political actors.

- One of the hardest challenges for progressive and left-leaning movements that come to power is how they will change the neoliberal system from within the government and ensure the sustainability of systemic alternatives and its elements against a global context still dominated by the capitalist world order. In Latin America, one of the key questions for the left was how to reverse neoliberal policies, especially privatization. The general belief among the left is that once they enter the government, they will have to put everything under the control of the state in order to reverse privatization. However, nationalization is not the only way to push back against privatization. The state cannot and should not be in control of everything. Rather, different industries, services, and resources should be regarded as commons. Viewed from this light, the key role of the state is thus to facilitate the process of distributing ownership of these to communities and social movements.