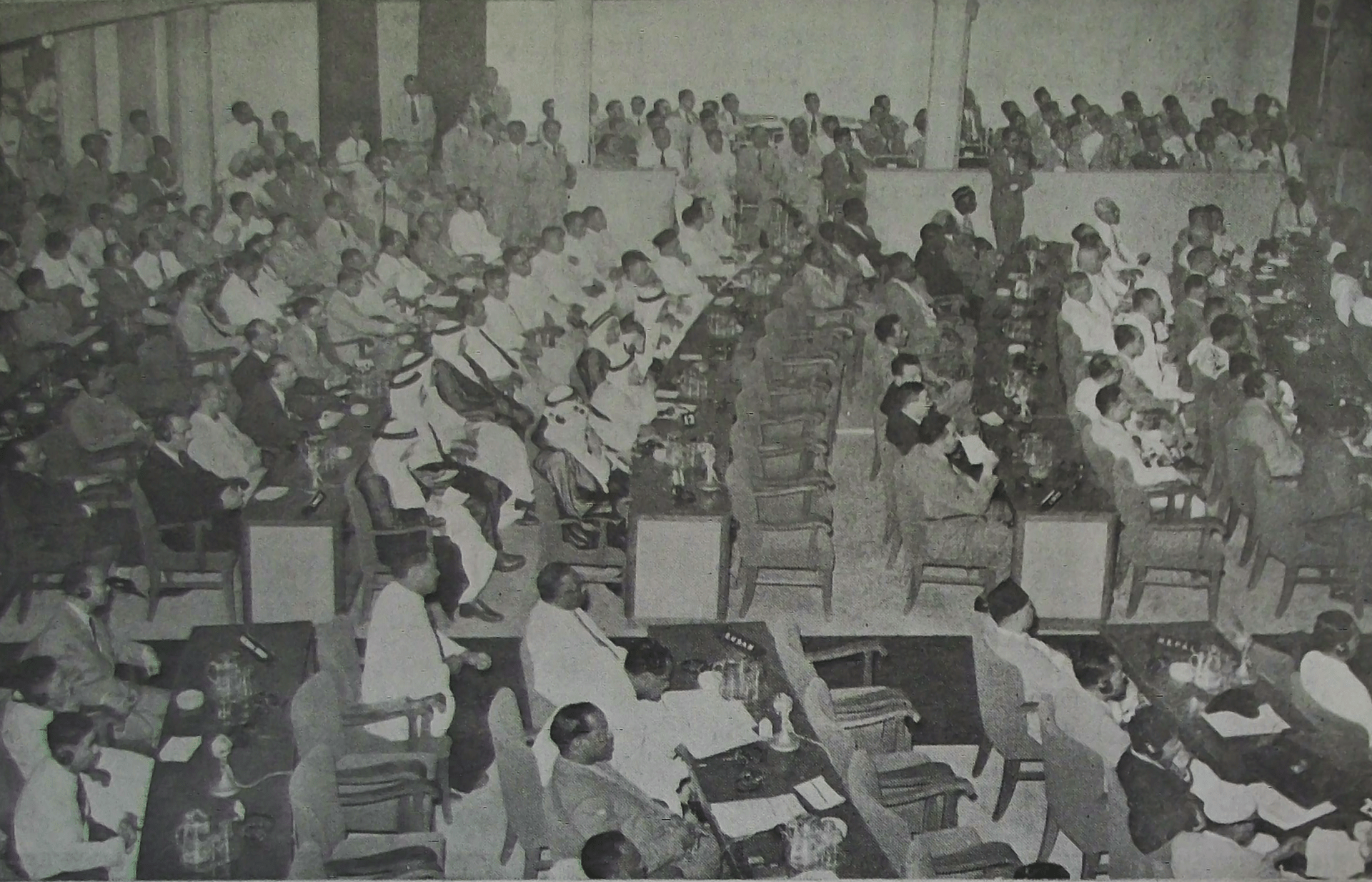

Between 18 and 24 April 1955, 29 nations from the continents of Asia and Africa gathered at Gedung Merdeka, Bandung, Indonesia, marking a critical moment for newly independent nations to stand tall on the world stage. Wikimedia Commons.

This article is part of a series marking the 70th anniversary of the 1955 Bandung Conference. A turning point in anti-colonial and South-South solidarity, Bandung’s legacy endures in today’s global struggles for justice and self-determination.

Read the rest of the series at focusweb.org/tag/kaa70.

Zhou En Lai: The Consummate Diplomat in Bandung

by Walden Bello

Zhou En Lai, the People’s Republic of China’s chief representative at the Bandung Conference, was a key actor in all the major phases of the Chinese Revolution.

He was a leading organizer of the Communist Party-led workers’ uprisings in Shanghai in 1927, which were crushed by the Nationalist forces under Chiang Kai Shek. He directed the Communist Party espionage activities in the coastal cities, in which role he was able to escape arrest several times while inflicting damage to the Nationalist spy network. During the Long March he sided with Mao Zedong in the latter’s efforts to reorient the strategy of the Chinese Revolution, gaining the latter’s support in the twists and turns of the intra-party struggles in the succeeding decades. He negotiated the United Front with the Nationalists in 1937, which left the Communists relatively free from attacks by the Nationalists while leaving most of the fighting against the Japanese to the latter. What one historian described as his “suave diplomacy” in dealing with western visitors during the civil war gave the Communists an image of being pragmatic, non-doctrinaire reformers.[i]

He became Prime Minister of China upon the Communist assumption of power in 1949, retaining that position until his death in 1976. At his first major international conference, the Geneva Conference of 1954 that ended French colonialism in Indochina, Zhou’s interesting encounter with the US government, which China had fought to a stalemate in the Korean War, was described by one analyst:

[At the Conference] Secretary of State John Foster Dulles…deliberately and sullenly evaded being introduced to him. The lead negotiator, former CIA chief Walter Bedell Smith, had been careful to keep a coffee cup in his right hand, to avoid shaking Zhou’s. He used his left hand to shake my arm,” recalled Zhou in 1972.[ii]

But the American delegates’ snub was more than made up for by Zhou’s meeting with the famous comedian Charlie Chaplin, a campaigner for peace, at the sidelines of the conference. After Zhou regaled Chaplin with stories of the historic nearly 10,000-kilometer Long March, the astounded Chaplin assured Zhou that he would never have to walk that far again.[iii]

His performance at the Bandung Conference gave him the image that the world had of him in the decades to come: reasonable, affable, charming, and polished. An American observer provided this memorable sketch of him in action:

During the early days of the conference, he played a patient, conciliatory, and one might say even defensive role. When attacks were made against the Communists, he kept his temper. He refrained from any of the propaganda blasts which typify Chinese Communist pronouncements from Peking. He did not assert himself, and for the most part, he stayed in the background. Then, on the last three days, he emerged as the main performer, and in a series of fairly dramatic diplomatic moves he assumed the role of the reasonable man of peace, the conciliator who was willing to make promises and concessions in the name of harmony and good will.[iv]

Zhou’s relationship to Mao was complicated. He never strayed away from his loyalty to Mao, to the point that critics after his death would say he was “slavish” in his obeisance to the latter. At the same time, although he seemed to occasionally doubt Zhou’s obedience to him, Mao could not do without Zhou’s skills in stabilizing China even as he was destabilizing it with his Red Guards’ assault on the Communist Party establishment.

Zhou sought not only to protect himself but others who were politically or personally close to him, but he was sometimes unsuccessful. He was close to his fellow pragmatist, Deng Hsiao Ping, but this did not prevent Mao from purging Deng twice. His adopted daughter, the artist Sun Weishi, died in 1968 after enduring several months of torture by Red Guards.[v]

Perhaps Zhou’s most celebrated achievement was his negotiating President Richard Nixon’s historic visit to China in 1972 with US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. In his dealings with Zhou, Kissinger was completely won over by the Chinese premier. As one historian of their relationship notes,

I cherish deep feelings for Zhou Enlai,” Kissinger said. His writings are filled with praise for Zhou’s and Mao’s skill, subtlety, and intelligence, and for the “brilliant” way Chinese leaders approached international relations. At dinner parties he stunned guests with testimonials to his “adoration” of Zhou.[vi]

It was in one of his meetings with Kissinger that Zhou made his celebrated remark that showed his Chaplinesque sense of humor. Asked by Kissinger what he thought about the impact of the French Revolution, Zhou answered, “It’s too early to tell.”

Towards the end of his life, Zhou drew up the “Four Modernizations” Program for China, even as the country was still in the throes of the Cultural Revolution. It would be the program enacted by Deng, upon the latter’s coming to power after Mao’s death and the ouster of the so-called “Gang of Four” that had surrounded Mao. It is generally regarded as the blueprint that launched China onto its ascent to become the world’s No 1 (or No 2, depending on the metric used) economy in a record time of 40 years.

———

[i] Robert Bickers, Out of China: How the Chinese Ended the Era of Western Domination (UK: Penguin Books, 2018), p. 237.

[ii] Ibid., p. 359.

[iii] “Cultural Diplomacy at the Sidelines of the Geneva Conference,” China Daily, June 15, 2021, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202106/15/WS60c80a79a31024ad0bac6c77.html

[iv] A. Doak Barnett, “Chou En-Lai at Bandung,” American Universities Field Staff,” May 4, 1955, https://www.icwa.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/ADB-77.pdf

[v] Catherine Faulder, “A Childhood Spent in a Dragon’s Den,” Bangkok Post, July 19, 2015, https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/special-reports/626888/a-childhood-spent-in-the-dragons-den

[vi] Barbara Keys, “Friendship in International Relations: Henry Kissinger and Zhou Enlai,” American Historical Association, 131st Annual Meeting, Denver, Jan 15-18, 2017, https://aha.confex.com/aha/2017/webprogram/Paper20864.html

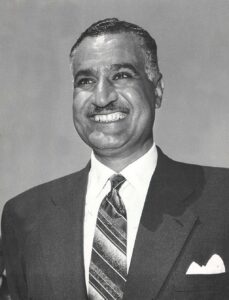

Gamal Abdel Nasser, the Arab Voice in Bandung

by Walden Bello

One of the most consequential events of the 20th century took place on July 26, 1956, when Egyptian President Gamal Adbel Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal. Previously, the Canal had been run by a private company controlled by British and French shareholders backed by the power of the governments of France and Britain.

Seizing the Suez Canal

Nasser’s move led the British, French, and Israeli governments to hatch a plan to take back the Canal. Israel was to move across the Sinai desert to clear it of Egyptian troops, and, while Nasser was distracted by the Israeli incursion, British and French troops would seize the Canal. The military moves were successful, but they provoked a diplomatic storm. Angered because it had not been informed of the Canal’s seizure by its British and French allies and worried about the global impact of a brazen colonial action, the Eisenhower administration warned the three conspirators to withdraw or face economic sanctions. In fact, the US sold its sterling bonds, thus provoking a devaluation of the British currency.[i]

These moves plus the condemnation of the United Nations forced the withdrawal of the troops of the three countries from the Canal. This retreat was later widely seen as the sunset of both British and French colonial power, and underlined the status of the two countries as satellites of the United States in the post-World War II era.

Nasser’s victory at Suez made him a hero not only to the Arab world but also to the Global South as a whole.

Nasser at Bandung

When Nasser attended the Bandung Conference more than a year before the Suez events, he still had not achieved his glittering reputation, though he was regarded as a charismatic Arab leader. He had led the Free Officers’ Movement that took power in 1952, had introduced genuine land reform, and, after surviving an assassination attempt, had become chief executive before being formally designated president in June 1956, a month before his seizure of Suez.

At Bandung, Palestine was at the center of Nasser’s intervention. He asserted:

Under the eyes of the United Nations and with her help and sanction, the people of Palestine were uprooted from their fatherland, to be replaced by a completely imported populace. Never before in history has there been such a brutal and immoral violation of human principles. Is there any guarantee for the small nations that the big powers who took part in this tragedy would not allow themselves to repeat it again, against another innocent and helpless people?”[ii]

Owing to the hesitation of some delegations, however, Nasser was not able to secure a condemnation of Israel at Bandung. Nevertheless, the final declaration did assert “its support of the Arab people of Palestine and called for the implementation of the United Nations Resolutions on Palestine and the achievement of the peaceful settlement of the Palestine question.”[iii]

Nasser after Bandung

Over two years after Bandung, Nasser hosted the Afro-Asian Solidarity Conference held in Cairo in late 1957. This was dubbed the “second Bandung,” with Anup Singh, secretary of the preparatory commission, declaring: “Let Cairo be the People’s Bandung.”[iv]

Nasser went on to become one of key founders of the Non-Aligned Movement in September 1961, along with Josip Bros Tito of Yugoslavia, Jawharlal Nehru of India, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, and Soekarno of Indonesia.

An outspoken Pan-Arabist, Nasser led the formation of the United Arab Republic uniting Egypt and Syria, in 1958, but this venture fell apart in 1961 after a military coup in Syria.

Nasser’s reputation was tarnished by Egypt’s defeat during the1967 war with Israel. At the time of his death from cardiac arrest in 1970, however, he was still an iconic figure revered by the Arab masses.

———

[i] Remembering the Suez Crisis and the tripartite invasion of Egypt, Middle East Monitor, Oct 29, 2022, https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20221029-remembering-the-suez-crisis-and-the-tripartite-invasion-of-egypt/

[ii] Quoted Joseph Massad, “Palestine at Bandung: How the Historic Asia African Conference Challenged Imperialism,” Middle East Eye, April 4, 2024, https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/palestine-bandung-how-asian-african-conference-challenged-imperialism

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Quoted in Joseph Hongoh, “The Asian-African Conference (Bandung) and Pan- Africanism: the Challenge of Reconciling Continental Solidarity with National Sovereignty, Australian Journal of International Affairs, 70:4 (2016): 374-390, DOI: 10.1080/10357718.2016.1168773, p. 382.

Carlos P. Romulo: Can an American Boy be Anti-Colonial?

by Bianca Martinez and Joseph Purugganan

Carlos Peña Romulo–soldier, journalist, and diplomat- led the Philippine delegation to the Bandung Conference in 1955, where he represented what many considered as the pro-american, anti-communist, and anti-colonial perspective and agenda..

The Philippines was formally granted independence by the Americans on July 4th 1946 after enduring a brutal Japanese occupation (1941-1945) during the Second World War, where America was largely portrayed as the country’s liberator and saviour. One of the iconic images depicting this US-Philippines relationship during the time is that of General Douglas McArthur, flanked by President Sergio Osmeña, and Philippine Army General Carlos P. Romulo. This image accompanied the news of the return of the Americans after its retreat to Australia in 1941.

Philippine President Sergio Osmena Kenney (almost completely hidden), Colonel Courtney Whitney, Philippine Army Brigadier General Carlos Romulo, MacArthur, Sutherland, CBS correspondent Bill Dunn, and Staff Sergeant Francisco Salveron (left to right) wade ashore just south of Tacloban at Palo, Leyte, October 20, 1944. Courtesy of the MacArthur Memorial, Norfolk, VA.

The Philippine perspective that Romulo, known for his oratorical skills, articulated at Bandung had a strong anti-communist message, echoing the Cold War rhetoric after the war, but combined and couched with references to common concerns over “colonialism and political freedom, racial equality and peaceful economic growth.”

As one writer put it, Romulo was carrying water on his two shoulders. On the one hand, taking on the task of “chronicler and herald” of America’s relationship with the Philippines and with the rest of the region– how the granting of independence by the United States to the Philippines “showed the far east that their fellow Asians could be free and govern themselves.” And on the other hand, trying to push for an alternative, albeit a less radical anti-colonial vision.

In a subsequent lecture in the University of North Carolina entitled the Meaning of Bandung delivered in 1956, on the first anniversary of the conference, Romulo described the role he and other pro-western voices in the conference played in challenging what he referred to as the neutralist agenda advanced by Nehru of India.

“Neutralism, these States would have us believe”, said Romulo, “takes no side in ideological conflict or cold war between the free and Soviet worlds.” He added that by “equating democracy and communism, democracy is already undermined”.

Romulo further expounded on this point on the issue of nuclear disarmament, arguing against what he perceived as the problematic neutralist position of “ outlawing nuclear and thermo-nuclear weapons, prohibiting their manufacture and use, and vocal opposition to further atomic experiments by the West in the Pacific while discreetly (being) silent to the atomic experiments in the Soviet Union.” This prohibition, Romulo argued, would “strip the free world of its deterrent and primary defensive power lodged in the atomic superiority of the United States.”

Under America’s shadow

To understand the origins of the liberal anti-Communist position that Romulo advanced in the Bandung conference, it is important to consider the key historical moments that shaped his worldview.

Romulo was born in the Municipality of Camiling in Central Luzon on January 14, 1899, and grew up in a milieu where Americans had already successfully subdued the Filipino revolutionary movement for independence and engineered a social and political environment favorable to entrenching American control over the Philippines.

After the US victory in the Spanish-American War of 1898, it sought to “pacify” the Filipino revolutionary movement that resisted American colonial rule. This “pacification” took two forms: a benevolent approach, where social reforms and welfare projects were implemented by American occupiers to gain Filipinos’ trust, and a violent approach, which involved torturing, repressing, and executing revolutionaries. The benevolent approach resulted in the co-optation of large sections of the revolutionary movement, especially those from elite classes influenced by European liberalism and who saw alignment between their visions and American social reforms. Meanwhile, the violent tactics—including re-concentrating populations and imposing terror on revolutionaries and their supporters—created a chilling effect and social polarization, thereby making the revolutionaries’ guerilla warfare tactics more difficult to sustain.

A number of revolutionaries thus surrendered in the following years, including Romulo’s own father, Gregorio. As a young boy, Romulo vowed to “hate [the Americans] as long as [he] lived.” But this resentment dissipated when he entered high school, thanks to the influence of the Americanized education system established through the US’ benevolent assimilation policy. After high school, Romulo attended college from 1918 to 1921 in Columbia University, where his belief in American liberalism and benevolence was further reinforced.

Upon returning to the Philippines, Romulo worked for years under Manuel Quezon and was deeply influenced by his politics. Quezon, who was elected the first president of the Commonwealth of the Philippines under American rule, represented to Americans the “acceptable” way of advancing social change—not with warfare as the revolutionaries did, but from his “dynamic ability to mobilize followers through personal relationships.” Figures like Quezon appeased Filipinos’ nationalist tendencies without being antagonistic towards the US.

Romulo often portrayed US-Philippine colonial relations positively, expressing his feelings of indebtedness to Americans for the “privilege of believing in democracy” and viewing America as a “generous benefactor” and a “loyal friend.”

Romulo believed that achieving independence and establishing liberal democracy in the Philippines required working with the Americans, not against them. While he criticized the US when it violated liberal values, he recognized America’s global power and accepted it, viewing it as essential to work with the US in ways that appealed to their “benevolence” to gain benefits. This approach defined his colonial discourse throughout his political career.

Post Bandung: the Philippines and Southeast Asia

Cold War geopolitics pretty much dictated Philippine foreign policy after Bandung, with the tensions between the West led by the United States and Western Europe on the one hand, against the communist Eastern bloc of Russia, East Germany and China that played out in wars and conflicts in the Korean Peninsula, Vietnam, Kampuchea and on issues of nuclear non-proliferation and broader regional security issues.

Aligned more with the West, the Philippines played key roles in the forging of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) and subsequently of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO)- 1954-1977

Patterned after the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), SEATO was a collective defense treaty signed by the United States, France, Great Britain, New Zealand, Australia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Pakistan. Its formation was a response to the “demand that the Southeast Asian area be protected against communist expansionism, especially as manifested through military aggression in Korea and Indochina and through subversion backed by organized armed forces in Malaysia and the Philippines.”

ASEAN (1967- present)

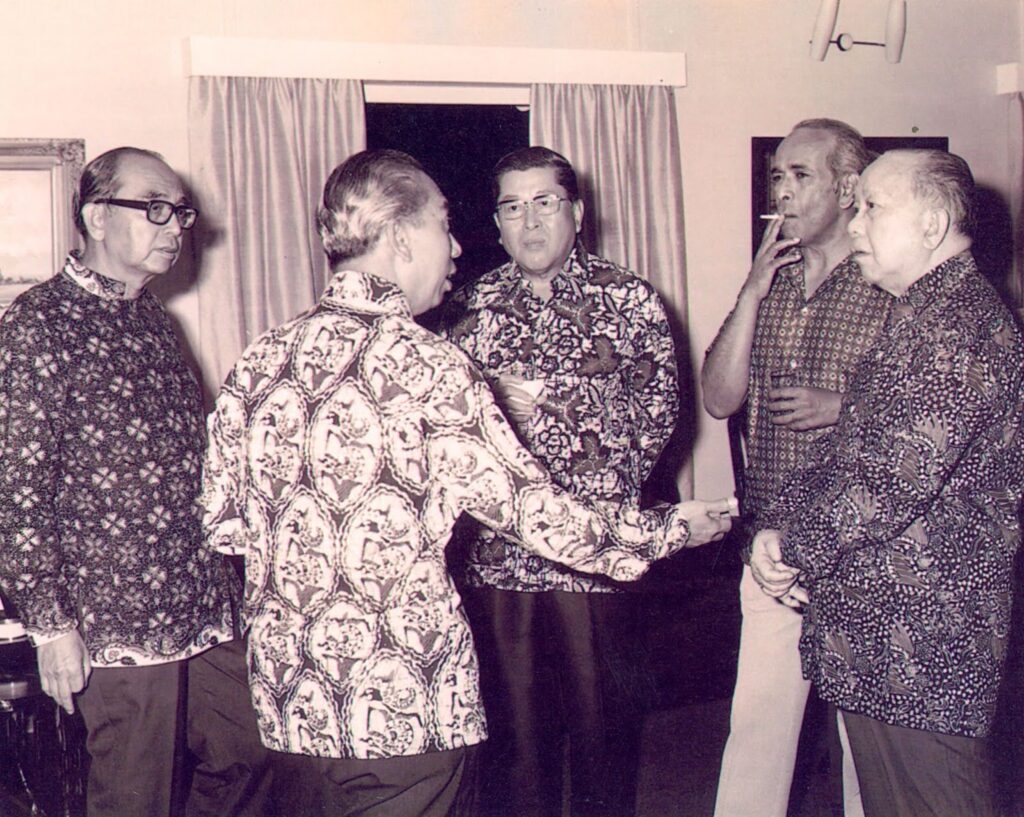

This photo of the “ASEAN-5” was taken in November 1971, during a Special ASEAN Foreign Ministers Meeting hosted by Malaysian Prime Minister Tun Abdul Razak (far left). All five ministers had gathered in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to issue the declaration on the zone of peace, freedom, and neutrality. The photo illustrates perfectly the “ASEAN Way,” a working style that is informal, personal, consensus-based, and open to compromise. Philippine Foreign Minister Carlos P. Romulo listens to Indonesian Foreign Minister Adam Malik while Singapore’s Foreign Minister S. Rajaratnam and Thai special envoy Thanat Khoman (center) look on. From https://www.carlospromulo.org/journal/2021/7/28/asean

The formation of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1967 is largely seen as the jewel of this anti-communist crusade in Southeast Asia. ASEAN was formed as an alliance originally among the five countries of the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand, to “unite against the spread of communism and to promote stability in the Southeast Asia region.”

Under the Marcos administration, the Philippines “normalized economic and diplomatic ties with China and the USSR, and opened embassies in the eastern bloc countries, as well as a separate mission to the European Common Market in Brussels. The Department of Foreign Affairs also highlights in its history how “throughout the 1970s, the Department pursued the promotion of trade and investments, played an active role in hosting international meetings, and participated in the meetings of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM).”

As Minister of Foreign Affairs under Ferdinand Marcos, Sr., Romulo oversaw the administration’s foreign policy, which was “redefined as the safeguarding of territorial integrity and national dignity, and emphasized increased regional cooperation and collaboration. He stressed “Asianness” and pursued a policy of constructive unity and co-existence with other Asian states, regardless of ideological persuasion”.

He resigned from the Marcos cabinet soon after the assassination in 1983, of Senator Benigno Aquino, whom Romulo considered a friend. Even as a private citizen, he continued to advocate for reforms in the United Nations, specifically an amendment to its charter “by convening a sort of constitutional convention”, in order to remain relevant in light of global conflicts. He argued “that the world body should acquire a permanent military force of several thousand troops and that nations at war should be required to submit their hostilities to negotiation.”

Romulo died on December 15, 1985, at age 87, in Manila, and was buried in the Heroes’ Cemetery (Libingan ng mga Bayani) at Fort Bonifacio, Metro Manila. #

Sukarno: The mind and heart of the Bandung Conference 1955

by Henry Thomas Simarmata* and Dhia Prekasha Yoedha*

When Sukarno was arrested by the Dutch colonial authorities and detained in Banceuy Prison in Bandung in 1929, he was acutely aware that he needed to express his ideas and vision for a nation, a world free from humiliation and exploitation by others. While in prison, he wrote his pledoi (legal defense) titled “Indonesia menggugat” (often translated as “Indonesia Accuses” or more accurately, “Indonesia Calls for the End of Colonialism”). This pledoi was presented in court in Bandung in 1930. This legal defense was unique in that it used a colonial setting while providing a valuable opportunity to advocate for a unified voice against the dissolution of colonialism. He mentioned very little about himself in the defense.

Before, during, and after this pledoi, Sukarno consistently advocated for a unifying voice for independence. He collaborated closely with various individuals and groups, including ethnic communities from diverse backgrounds and perspectives. Sukarno’s ability to play this role stemmed from his understanding that independence encompasses both struggle and ideology. In and out of prison throughout the 1930s and 1940s, he continued to engage with numerous individuals and groups who were calling for and working toward independence. During this time, Sukarno began to openly contemplate the unifying values of independence, which later evolved into Pancasila.

During the Japanese Occupation from 1942 to 1945, Sukarno again utilized the occupier’s setting of the Chuo Sangi In (The Central Body for Consideration) established in 1942, which then became BPUPK (Badan Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia/The Body for the Preparation of the Independence of Indonesia) in 1945, marking a significant push for independence. Sukarno’s idea resonated as a call for “Indonesia Merdeka selekas-lekasnya” (Independence of Indonesia as soon as possible). Throughout this period, mainly while he was engaged in various discussions within the BPUPK, he became more aware of reality than ever before. He recognized that the colonialism he experienced closely resembled the European colonialism he had understood, paralleling the colonialism of the occupier. In his speeches, he referenced the Asian struggle for independence. Without inciting hatred against Europeans or other Asians, he highlighted the flaw inherent in any colonialism: the exploitation of humans by other humans (often, he expressed this in French, l’exploitation de l’homme par l’homme).

On August 17, 1945, Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta, his fellow “proklamator,” initiated Indonesia’s stance against “anti-exploitation.” Despite the challenges of the first five years of independence, Sukarno, as the president of Indonesia, actively participated in international fora, including the newly formed United Nations, supporting fellow Asian nations seeking independence, such as India, Burma, Vietnam, and Ceylon, among others. As the 1950s approached, he recognized that Asia and Africa were regions where European colonialism attempted to reestablish itself after World War II. Sukarno was determined to accelerate the decline of European colonialism in Asia and Africa. The experience of Indonesia’s fight for independence, particularly against the comeback of the Dutch backed by the Allies, underscored the necessity to end colonialism. Asia and Africa should never again serve as extensions of European colonialism.

The Bandung Conference of 1955 represented an amalgamation and mutual recognition of independence among the peoples of Asia and Africa. Sukarno and Nehru were both key drivers of the Bandung Conference. Still, the leaders of Asia and Africa were also very active, working alongside Sukarno and Nehru to promote the ideal of self-determination free from exploitation by others. Sukarno engaged all leaders of Asia and Africa and made significant efforts to seek a unifying voice against colonialism and exploitation. Meetings and discussions were held in preparation for the Bandung Conference.

In his opening speech at the Bandung Conference on April 18, 1955, Sukarno called for awareness of the ongoing presence of colonialism. “We are often told, “Colonialism is dead.’ Let us not be deceived or even soothed by that. I say to you, colonialism is not yet dead. How can we say it is dead so long as vast areas of Asia and Africa are unfree”

The Dasasila Bandung (Ten Principles of Bandung) was the call of the 1955 Bandung Conference. Today, it is primarily enshrined in the UN Declaration on the Right to Development. These principles are the foundation of the Non-Aligned Movement (in Indonesia: Gerakan Non-Blok). On September 30, 1960, before the UN General Assembly, Sukarno reaffirmed this principle in his famous speech “Membangun Dunia Kembali,” or “To Build the World a New.”

After the Asia-Africa Conference 1955, Sukarno, in some ways, predicted that the opposition by the colonial power and its extension against independence of Asia-Africa nations would morph into a boycott against the affair of Asia-Africa nations. Sukarno did not abandon his balanced attitude towards other nations, including the west, but he resisted the use of polarising international deliberation and of foreign aid to drive Indonesian and Asia-Africa decision-making. He kept on promoting diversity by empowering international decision-making through NAM (Non-Aligned Movement). The famous “newly emerging forces” or NEFO was Sukarno’s choice of attitude (as against “old established forces” or OLDEFO). He promoted sports and exchange of intellectuals as a way to keep Asia-Africa as power to be understood, and as a way to defuse tensions.

Sukarno was deposed with the coming of “New Order”, a military-political establishment. The tragedy of the 1965 coup remains elusive and varied in interpretation until today. One thing is clear, though, that the generational stature of Sukarno was deliberately ended by the New Order starting in 1965-1966. The policy of “anti-communism” then started to be used and abused by the New Order as a way to control and dominate the society. However, his stature was unmatched in the nation in 1965 until he passed away in 1970. He still commanded a strong influence towards attitude of the nation. The general public was still very much in tune towars towards what Sukarno said. Despite harsh treatment of the New Order against Sukarno, Sukarno kept persuading general public to seek middle way in engaging New Order. He once said that he did not want a bloodbath in provoking general public to defend him against the New Order.

His stature is still unmatched in realising Dasasila Bandung. Until now, “Non-Aligned Movement” (NAM) is still the anchor of Indonesian key policies and political attitude. Especially out of initiatives and works by intelligentsia, journalists, environment activists, educators, the Dasasila Bandung is translated into a pursuit of equality between nations. The pursuit is to prevent domination of one power against the well-being of many. This pursuit is targeted into a peaceful (non-violent, non-aggressive) achievement of rich and shared Asia-Africa well being.

——-

*Henry Thomas Simarmata & Dhia Prekasha Yoedha/ IAAC-Indonesian Institute for Asia-Africa Conference 1955

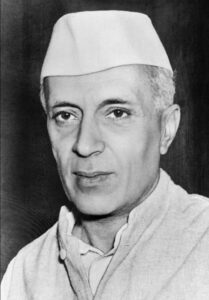

Jawaharlal Nehru and the spirit of anti-colonial non-alignment

by Meena Menon

The idea of the Bandung Conference (April 18 to 24, 1955) as a meeting of independent countries of Asia and Africa, took shape as part of a process that came out of the need for these countries to come together to strengthen the decolonization process, and to hold their own in the Cold War world, dominated by the two superpowers, the USA and the Soviet Union.

Jawaharlal Nehru was a central figure in charting a path for the new formally independent countries.

Newly independent countries were faced with many challenges – finding themselves in the position of governing large populations facing poverty, illiteracy and worse. Support and solidarity were essential. The Bandung conference aimed to promote Afro-Asian economic and cultural cooperation and to oppose colonialism and neocolonialism.

Prior to the Bandung Conference, the prime ministers of Burma, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Ceylon (present day Sri Lanka) met in Bogor, Indonesia, in December 1954, and reached an agreement on co-convening an Asian-African conference, and to request Indonesia to host it.

Before the Bogor Conference, Jawaharlal Nehru, heading what was then the Provisional Government of India before official hand over of power in August 1947, hosted an Asian Relations Conference in Delhi 23 March to 2 April, 1947, a full 10 days. Since a provisional government could not officially host an international conference, a private body, Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA) was the organiser. The Asian Relations Conference brought together many leaders of anti-colonial independence movements in Asia, and represented a serious attempt to assert Asian unity. Although the Conference was ostensibly a ‘cultural conference’ it did not steer clear of important political issues, and in fact even of many internal issues such as China-Tibet . The Prime Minister of Indonesia Sutan Sjahrir missed the opening session of the Asian Relations Conference as he was signing an agreement with the Dutch, but Nehru sent a chartered plane that allowed him to arrive in time for the closing ceremony. An Indonesia delegation was present, since the country had declared its independence on August 17, 1945, although the Dutch was to formally recognize this independence only on December 27, 1949. Participation in Nehru’s Asian Relations Conference was remarkable in many ways. There were China and Tibet, French Indochina and Vietnam, the Jewish delegation, Egypt and Arab League, Soviet republics.

An excerpt from Nehru’s speech at the 1947 Conference could easily be part of a speech written for today:

“so even in meeting we have achieved much and I have no doubt that out of this meeting greater things will come. When the history of our present times is written, this event may well stand out as a landmark which divides the past of Asia from the future, and because we are participating in this making of history, something of the greatness of historical events comes to us all……We seek no narrow nationalism. Nationalism has a place in each country and should be fostered, but it must not be allowed to become aggressive and come in the way of international development. Asia stretches her hand out in friendship to Europe and America as well as to our suffering brethren in Africa. We of Asia have a special responsibility to the people of Africa. We must help them to take their rightful place in the human family.”

A second Asian Relations Conference was to be held in Nanking, China in April,1949, but due to the Chinese Civil War, it was held in Baguio, Philippines in May 1950. Nehru was instrumental in blocking a proposal for the creation of an Asian Regional Organisation that was made in the meeting. India’s (and Gandhi’s) non-alignment was one that was put peace at the centre, and any military alliance directed or seeming to be directed against Europe and the US was not acceptable.

Jawaharlal Nehru – his life

Nehru came from an educated wealthy family, settled in Allahabad (now renamed Prayagraj by the Hindu nationalist government) in Uttar Pradesh. His father was an eminent lawyer and a moderate member of the Congress party. He was educated by British tutors first and then went to Harrow and Cambridge, after which he trained as a lawyer, since he was meant to be following in his father’s footsteps. His exposure to liberal and radical writers while in England, his deep interest in the history and culture of his country and his burning faith in the India’s future as an independent country, led him to jump into active politics when he returned to India. In the mid-1920s, he became a national figure by assuming leadership of the radical youth wing of the party. He was not afraid to challenge the party’s old guard including Gandhi. He first became Congress President in 1929 at a relatively young age of 40. He campaigned inside the party for complete independence from Britain and soon Gandhi declared that the time had come to start this phase of the battle. Nehru was friendly with the communist parties and he was deeply influenced by his reading of Marxism and the achievements of the USSR. He thought of China not as a political fellow traveler but as a potentially important ally to build an anti-colonial non-aligned bloc in which in his view India must play a leading role.

The history of India has become a matter of bitter debate today in domestic politics, when a hundred years after the peak years of the Indian Independence movement, its history and that of the Congress Party, especially Jawaharlal Nehru is being challenged and rewritten from the point of view of what was once a fringe group in the country’s political landscape. The anti-colonial struggle encompassed almost all political ideologies and tendencies in India. But today a politically dominant Hindu nationalist discourse is fighting for space they believe was denied to them in the writing of the history of the Indian anti-colonial movement. As a result, contemporary Indian history is now a battlefield, spotted with hidden mines which can explode into violence and bloodshed without much warning. As many histories have shown, any attempt to force a single historical narrative has always been a sensitive and dangerous game.

Nehru’s foreign policy

Nehru saw internationalism and nationalism as two sides of the same coin. Even before freedom in 1947, while in prison, he wrote:

“Sometimes we are told that our nationalism is a sign of our backwardness and even our demand for independence indicates our narrow-mindedness. Those who tell us so, seem to imagine that true internationalism would triumph if we agreed to remain as junior partners in the British Empire and the Commonwealth of nations. ……..Nevertheless, India, for all her intense national fervour, has gone further than many nations in acceptance of real internationalism and the coordination and even to some extent, the subordination of the independent national-state to a world organization”. (Discovery of India, 1946)

The 40’s saw a slew of countries throwing off the colonial yoke. But once that was done, the challenge of rebuilding was daunting to say the least. Clarity of priorities, finding common ground, identifying the main pillars of solidarity needed an engagement beyond national boundaries, especially in the era of the Cold War. From this came the ideology of non-alignment as the preferred foreign policy of the developing world. NAM was a progressive movement although it was a movement of countries, not to be confused with a mass movement. India and China were the biggest actors, but China was still too close to the Soviet Union to be fully trusted by the NAM countries. India always saw this as an opportunity and was more than happy to be seen as leader of the non-aligned movement. Nehru led this ambition, but it has remained a part of Indian foreign policy to date whichever party was in power.

Nehru was the main architect of India’s foreign policy. It was said that India’s foreign policy could only be found in Nehru’s pocket. It is true that the foundations laid during his tenure as Prime Minister, that is from 1947 to 1964, i.e 17 years, it was Nehru who led Indian foreign policy, but naturally India’s priorities were more domestic than international. Nehru’s contribution to building a secular polity, laying the foundation for study and research in science and technology, all these are lasting contributions in the building of modern India.

Nehru’s internationalism mostly stemmed from than from a need to secure India’s borders, and to ensure regional stability for all Asians to prosper, ensuring peace and prosperity for all. The attempt to forge friendship with China was a step in this direction. So was Panchsheel, or the Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence, first formally enunciated in the Agreement on Trade and Intercourse between the Tibet region of China and India signed on April 29, 1954, which stated, in its preamble, that the two Governments “have resolved to enter into the present Agreement based on the following principles:

- Mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty,

- Mutual non-aggression,

- Mutual non-interference,

- Equality and mutual benefit, and

- Peaceful co-existence

These principles, ironically, remained a cornerstone of official Indian foreign policy although just a decade later, China and India were at war over a border region. These principles were accepted as part of the resolutions that came out of the Bandung 1955 Conference.

Bandung and after

The Bandung conference in April 1955 declared their refusal to align with either superpower. After a debate, the USSR faced censure along with the US. The Non-Aligned Movement was founded. Thereafter, the first NAM conference was held in Belgrade in 1961 under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito (Yugoslavia), Gamal Abdel Nasser (Egypt), Kwame Nkrumah (Ghana), Sukarno (Indonesia) and Jawaharlal Nehru. NAM played an important role in deterring dangerous escalation of the Cold War, regional hostilities and the arms race caused by the two contesting global superpowers.

Nehru would best be described as a secular liberal democrat, but given that today a large section of those who think of themselves as being part of the left occupy a similar ideological space, his position in Indian history and politics will need to be seen from a contemporary lens, when right wing ideologies are often overpowering the ideological space world-wide. On a global level, in a world always on the verge of cataclysmic war, the role of NAM is perhaps more important than we have been given it credit for. It is important for people’s movements especially those who have been campaigning against war and nuclear arms, to push their own governments to build and support the principles of the NAM movement. In 2005, on the 50th anniversary of the original conference, leaders from Asian and African countries met in Jakarta and Bandung to launch the New Asian–African Strategic Partnership (NAASP). How do we view these attempts? What must a decolonized developing world do? It is impossible to ignore these questions now.

Cut Meutia: The Spirit of Anti-Colonial Resistance from Aceh to Bandung

by Anisa Widyasari

The Asia-Africa Conference (Konferensi Asia Afrika in Bahasa Indonesia, commonly known as KAA), held in Bandung from April 18 to 24, 1955, marked a significant milestone for countries in Asia and Africa striving to free themselves from the constraints of colonialism. The conference upheld fundamental principles such as respect for sovereignty, equality, and the rejection of all forms of oppression. Nevertheless, this spirit of anti-colonialism and quest for freedom has been deeply rooted in the historical struggles of nations in the region long before the KAA forum held.

One figure who embodies this spirit is Cut Meutia, a female warrior from Aceh.[i] Through her leadership during the Aceh War, Cut Meutia not only demonstrated unwavering resistance against Dutch colonial rule but also defied prevailing gender norms that sought to confine women’s roles to the domestic sphere. Her ability to command troops and engage in direct combat highlighted the active participation of women in anti-colonial struggles, challenging both colonial domination and patriarchal social structures. This reflection will examine Cut Meutia’s contributions, explore their relevance within the context of the KAA, and analyze their significance through contextual feminism[ii].

Brief Profile of Cut Meutia

Cut Meutia (Tjoet Nyak Meutia) was born on February 15, 1870, in Keureutoe, North Aceh, into a noble and devout Muslim family.[iii] She grew up in an environment that strongly upheld Islamic values and traditional customs, which played a significant role in shaping her sense of duty and resistance. In a patriarchal society where women were typically confined to domestic roles, Cut Meutia’s active participation in warfare was an extraordinary exception.[iv]

After marrying Teuku Cik Tunong, one of the prominent leaders of the Acehnese resistance against Dutch colonial rule, Cut Meutia became actively involved in the armed struggle. She was not merely a companion to her husband; she directly participated in battles and contributed to devising military strategies against colonial forces.[v] Following Teuku Cik Tunong’s execution by the Dutch in 1905, Cut Meutia assumed leadership, commanding the remaining troops and continuing the resistance despite dwindling resources and relentless Dutch attacks.[vi] She fought until her last breath, ultimately being killed in combat on October 24, 1910.[vii]

Her role as a female military leader during that era was remarkable. Not only did she symbolize resistance against colonial oppression, but she also represented the resilience, leadership, and courage of Acehnese women in the face of systemic challenges.

Cut Meutia in the Context of the Spirit of the KAA

One of the key principles affirmed in the KAA was the right of all nations to self-determination, as outlined in the Dasasila Bandung (Ten Principles of Bandung). Within these principles, which includes the respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations[viii], the conference reinforced fundamental values such as respect for self-determination, equality, and the rejection of colonialism and oppression.[ix]

Long before these principles were articulated in the KAA, Cut Meutia embodied this spirit of resistance and self-determination in Aceh. She led the fight for freedom from Dutch colonial domination, demonstrating that anti-colonial struggles were not solely the domain of men but also involved the active participation of women. Her determination and leadership paralleled the core values upheld in Bandung decades later, reinforcing the idea that colonial resistance was a universal struggle that transcended gender.

Furthermore, Cut Meutia’s resistance embodies the spirit of solidarity and resilience against oppression, a key theme of the Bandung Conference. The KAA emphasized that the fight for justice and independence is the right of all oppressed peoples, regardless of race, gender, or social status.[x] In this light, Cut Meutia’s legacy serves as a historical prove to the long-standing resistance movements that paved the way for Asia and Africa’s collective struggle for decolonization.

Feminism Perspective: Cut Meutia as a Representation of Contextual Feminism

Examining Cut Meutia’s struggle through a feminist lens, she represents a form of contextual feminism—a feminist resistance that is deeply rooted in the social, political, and cultural realities of her time. While she may not have identified as a feminist in the classical sense, her actions embodied feminist principles such as gender equality, women’s empowerment, and defiance against patriarchal structures.

This perspective aligns with Chandra Talpade Mohanty’s critique in Under Western Eyes (1984)[xi], where she challenges the Western feminist tendency to universalize women’s experiences while overlooking local contexts and historical struggles of women in the Global South. Mohanty argues:

“Sisterhood cannot be assumed on the basis of gender; it must be forged in concrete historical and political practice and analysis.”

In this light, Cut Meutia’s resistance was not only against Dutch colonialism but also against the structural patriarchy embedded in Acehnese society at the time. Her leadership in the battlefield, a role traditionally dominated by men, challenged the notion that women should remain confined to domestic spaces. This reflects the intersectional nature of her struggle, where anti-colonialism and gender resistance coexisted.[xii]

By situating Cut Meutia’s role within the broader discourse of contextual feminism, we acknowledge that feminist movements take different forms across historical and cultural landscapes. Her legacy challenges the homogenization of feminist struggles and highlights the agency of indigenous women in shaping their own narratives of empowerment and resistance.[xiii]

Cut Meutia’s Legacy in the Post-Colonial Era

Cut Meutia’s legacy continues to serve as an inspiration for the gender equality movement in the modern era. She demonstrated that women have the capacity to lead, make decisions, and drive social change, despite living in a deeply patriarchal society. While significant progress has been made, structural barriers to women’s participation in leadership, politics, and social movements still persist—echoing the same challenges she faced in her time.

In the context of the KAA, Cut Meutia’s spirit underscores that the fight against injustice must be inclusive, ensuring that all members of society—regardless of gender, class, or background—play an active role. Just as the KAA promoted international solidarity among nations fighting colonial oppression, the fight for gender equality also demands solidarity across socio-political and cultural divisions.

Beyond her direct involvement in anti-colonial resistance, Cut Meutia left a lasting impact on the historical narrative of women’s contributions to national struggles. Her story challenges the male-dominated discourse of independence movements, highlighting that women were not merely passive observers but active agents of change[xiv]. Her leadership in armed resistance not only defied colonial domination but also confronted entrenched patriarchal structures, making her a significant figure in both nationalist and feminist historiography.

In the spirit of the Asian-African Conference, Cut Meutia’s struggle serves as a powerful reminder that freedom and equality are universal rights—not only for nations but for all individuals, including women. Her legacy urges us to recognize that the fight against one form of oppression cannot be separated from the fight against others, reinforcing the need for an intersectional approach in post-colonial and feminist movements today.

——-

[i] Djajadiningrat, H. (1977). Tinjauan Kritis tentang Sejarah Perang Aceh.

[ii] Mohanty, C. T. (1984). Under Western eyes: Feminist scholarship and colonial discourses. Boundary 2, 12(3), 333–358. https://doi.org/10.2307/302821

[iii] Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan RI. (1996). Cut Meutia: Seri Pahlawan Bangsa. Jakarta: Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan.

[iv] Djajadinigngrat, H. Loc. Cit.

[v] Vickers, A. (2013). A history of modern Indonesia (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

[vi] Reid, A. (1969). The contest for North Sumatra: Atjeh, the Netherlands and Britain, 1858-1898. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

[vii] Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan RI. Loc. Cit.

[viii] Final Communiqué of the Asian-African Conference. In: Asia-Africa speak from Bandung. Jakarta: Indonesia. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 1955. pp. 161-169.

[ix] Kahin, G. M. (1956). The Asian-African Conference: Bandung, Indonesia, April 1955. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

[x] Mackie, J. A. C. (2005). Bandung 1955: Non-Alignment and Afro-Asian Solidarity. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet.

[xi] Mohanty. Loc. Cit.

[xii] Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139-167

[xiii] Pivak, G. C. (1988). Can the Subaltern Speak? In C. Nelson & L. Grossberg (Eds.), Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture (pp. 271-313). Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

[xiv] Jayawardena, K. (1986). Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World. London: Zed Books.

![[FS4P] Social movements, Indigenous Peoples, and civil society organizations continue to fight against the corporate capture of global food governance](https://focusweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Banner-media-impact-440x264.png)