By Ranjini Basu

The unfolding effects of the present global food crisis in India seems to be guided by a set of short-sighted approaches adopted by the Indian government which has had spiraling consequences for the country’s crucial food security and its vast masses of poor consumers. However, the larger impacts felt by the already distressed countryside due to three decades of neoliberal policies, cannot be discounted. Recent episodes of climate variations and extreme weather events have raised fears of further aggravation of the situation.

The Global Food Crisis, this time

A dossier by Focus on the Global South

A perfect storm is brewing in the global food system, pushing food prices to record high levels, and expanding hunger. The continuing fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine War, climate-related disasters and a breakdown of supply chains have led to widespread protests across the global South triggered by the spiraling food prices and shortages.

As international institutions struggle to respond, some governments have resorted to knee-jerk ‘food nationalism’ by placing export bans to preserve their own food supplies and stabilise prices. While this is an understandable defensive response, the solution lies in a more systemic, transformative approach.

In this dossier, researchers from Focus on the Global South write about various aspects of the current crisis, its causes, and how it is impacting countries in Asia. These include regional analysis, case studies from Sri Lanka, Philippines and India, the role of corporations in fuelling the crisis and the flawed responses of international institutions such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the Bretton Woods Institutions and United Nations agencies. We also attempt to present national, regional and global aspects of a progressive and systemic solution as articulated by communities, social movements and researchers at multiple levels.

Articles will be published every week till mid-October. Other articles included in the dossier can be found under this tag here.

Unfolding of the present crisis

In the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns, as streams of migrant workers left the urban centers and went back to their villages, Indian agriculture became the absorbent of the economic shocks. Supported by good monsoons and despite the rising cost of production, supply and labour disruptions created by the pandemic, there was a record acreage put under cultivation of foodgrains in the kharif or monsoon agricultural season of 2020.[i] Record production of foodgrains was achieved mainly due to the tireless efforts of the peasantry, and which ensured that in spite of the ongoing distribution of free foodgrains as part of the government’s Covid-19 response, the public stocks of buffer foodgrains never went below the desired levels.

However, earlier this year, things took a different turn. In March, just before the harvest season for the winter crop was to begin, a heatwave spanning across northern India, including Punjab, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh states which contribute to the majority of the country’s surplus wheat production, left farmers with shriveled grains and huge production losses. The early estimates say that the production loss may have been upto three percent less than previous years.[ii] In some wheat producing areas farmers reported a loss of as high as 30 percent of yield.

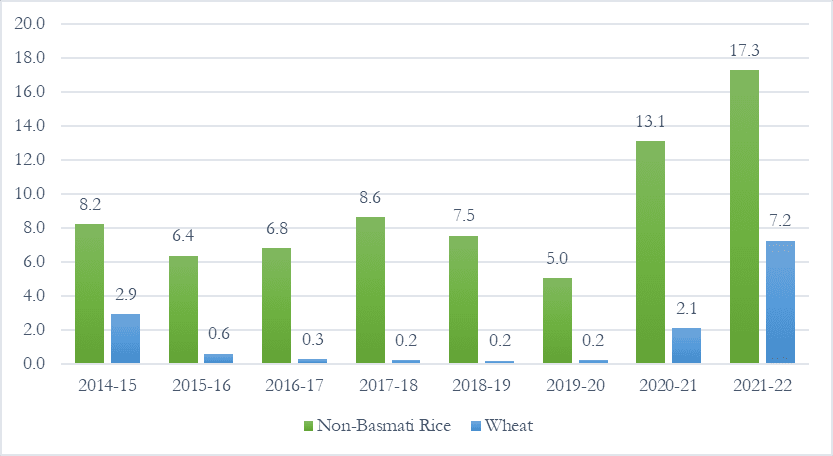

Meanwhile, the Russian invasion of Ukraine had started and the Indian government was eyeing the opportunity of gaining export markets for its wheat in the midst of global supply disruptions. The central government sent emissaries to look for probable buyers in the developing world, especially countries in South East Asia and Northern Africa. Prime Minister Modi proclaimed that, ‘India was ready to feed the world’. The Ministry reported that India was aiming to export 10 million tonnes of wheat in 2022-23.[iii] Even before the war, in 2020-21 India exported a record amount of wheat of 7 million tonnes as food-aid to various countries, largely driven by the Modi government’s attempts at projecting itself as a world leader.[iv] The steady rise in exports (see Figure 1) in the last two years is also driven by the government’s agricultural export driven policy, which seeks to diversify India’s export basket.[v]

Figure 1: Export of Non-Basmati rice and Wheat by India, 2014-2022, in million tonnes

Source: Agricultural & Processed Food Products Export Development Authority, Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Govt. of India

However, the government’s announcement of wheat exports came without an ear to the ground. With the export policy announced, a depleted production, and an inadequate procurement drive, the prospects of an emerging wheat crisis was in the offing. On the one hand, the Modi government did not make an attempt to raise the Minimum Support Price (MSP) of wheat during the rabi or winter season to cover the losses met to the farmers, while the private traders took this opportunity to offer a higher price and amass stocks to sell in the international market to make windfall profits.

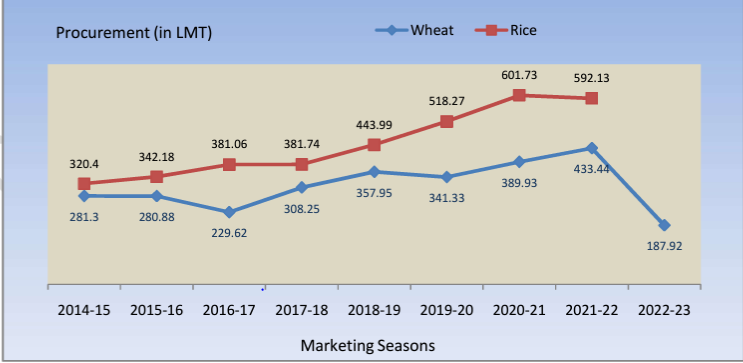

A 4 May, 2022 press bulletin from the Ministry of Food and Public Distribution noted that farmers in many northern states such as Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Gujarat were selling their wheat harvest to traders and exporters at Rs 21-24/kg, while the MSP was Rs 20.15/kg.[vi] Further, the brief noted that there were sections of farmers and traders who were holding onto their stocks to sell later at higher prices, thereby raising concerns of hoarding and inflationary trends. The procurement of wheat in the rabi season, that is in April-May 2022, was one of the lowest in years (see Figure 2). However, even at the lowest levels of procurement, the public stocks still managed to be above the threshold level, although marginally. In April 2022 the opening balance of wheat with the Food Corporation of India (FCI) was 18.99 million tonnes, whereas the buffer norms for the month was 21.04 million tonnes.

Figure 2: Procurement of wheat and rice by the Food Corporation of India

Source: Food Corporation of India

Facing a potential food security crisis and escalating prices, the Indian government backtracked from its earlier export plans and announced a wheat export ban on 13 May, 2022. Immediately there was an outcry, especially from the western developed countries, including the Group of Seven (G7) and International Monetary Fund (IMF), against India’s export bans, although India contributes only one percent of total world exports.[vii] The Indian government then announced that it will continue to export grains to countries to whom it had already committed, which included Bangladesh and Egypt.

Next, the government had to ban export of wheat flour and other wheat based commodities in August to rein in the spiraling food inflation that was already set in motion due to the earlier flip-flop policies of exports and inadequate public procurement. After the Indian wheat ban, there was a jump in demand for wheat flour in the international market. By August 2022 the domestic retail price of wheat had increased by 22 percent and wheat flour by 17 percent as compared to the previous year.[viii]

To counter the depleted public stock of wheat, the government decided to include 5.5 million metric tonnes of rice in the Covid-19 food distribution package of the government. There were reports suggesting a peculiar situation of poor- consumer households whose staple diet includes wheat, selling off the rice received from the Public Distribution System (PDS) to buy costly wheat from the open market.[ix] These conditions do not bode well for the already malnourished population, whose consumption is going to deteriorate due to the higher food prices.

The food inflation rates continue to be at worrying levels, above the stipulated levels fixed by the Reserve Bank of India (see Figure 3). This inflationary trend is feared to worsen further due to deficient monsoons in several parts of the country, leading to a shortfall in the paddy sown area during the present monsoon season, especially in the main paddy producing Eastern States. According to latest reports, the area under paddy this season fell by 5.51 percent as against last year, which may result in a deficit rice production of 6 percent.[x] Rice and wheat being highly weighted commodities in the consumer food basket, any rise in prices of these two commodities, would pinch the poor the hardest.

Along with the wheat troubles, India is also on the threshold of a rice crisis. With the decline in the availability of wheat in the world market, exporters have shifted to rice as an alternative foodgrain. As a result, India’s rice export, which is already the biggest in the world, saw an uptick in this current year. This, along with the smaller reserves of rice left in the public stocks and projections of shortfalls of rice production this year due to deficient rainfall, led the Indian government to announce on September 3, 2022, a ban on the export of broken-rice and an export duty of 20% on rice in husk (paddy or rough), husked (brown rice) and semi-milled or wholly-milled rice.[xi]

The opening balance of rice and unmilled paddy with the FCI at the beginning of September 2022 was 40.6 million tonnes, whereas the buffer stock norms for October 1 are stipulated at 30.7 million tonnes. The smaller public stock reserves of both rice and wheat also means a weakened position of the FCI to intervene in domestic price control through the Open Market Sale mechanism. Thus, these developments indicate that the unfolding of the present food price crisis in India is yet to take graver proportions in the coming days.

Figure 3: Retail and Food inflation in India

The Public Distribution System: from Famine to Food Security

Amidst the wheat fiasco and rising food prices on account of deficient production and rising global food prices, the policy track of the Indian government is marked by a complete disregard of the Public Distribution System. This view of the government towards food subsidy and the weakening of the Food Corporation of India, however, has been in the offing for a while. Therefore, it becomes necessary to review the historical role of the Public Distribution System in the country’s food security needs, especially in times of crises.

The rationing system in India was set up in 1936 under the British colonial rule as its war time policy. This system continued till 1954. However, the colonial policies during the Second World War led to the Bengal Famine of 1943, which claimed up to three million lives. Economist Amartya Sen wrote that the Bengal Famine was largely caused by the failure of the British colonial government to distribute adequate food grain, failure of exchange entitlements due to wage depreciation, and absence of market regulations.[xii]

In post-independence India, a permanent rationing system and other related institutions were set up only in the 1960s. The 1940s and 50s were marked by food shortages, which ultimately led to dependence on food aid from the United States.[xiii] The rise in production of foodgrains, although regionally skewed, which came in the aftermath of the Green Revolution, led to the establishment of the Food Corporation of India and the Commission for Cost and Agricultural Prices (CACP) in 1963. The idea was to procure surplus grains from the farmers at the Minimum Support Price fixed by the CACP and distribute it to deficit states through the Public Distribution System. Therefore, the mechanism was crucial to curtail the dependence on foreign food aid, which was increasingly becoming a threat to the country’s sovereignty, and achieve food security for its hungry masses. From the 1970s onwards, the PDS expanded beyond its role of stabilizing food prices, and started maintaining a buffer stock to distribute grains for welfare programmes on a universal basis. [xiv]

However, since the 1990s, in congruence with the structural adjustment policies adopted by the Indian government, there was a shift towards curbing the spending on food subsidy and making the PDS into a targeted programme. From 1997 to 2013, beneficiaries of the PDS were chosen on the basis of a poverty line, thereby limiting the scope of the welfare programme.

It was only in 2013 and due to the constant campaigning and advocacy of the Right to Food movement, and other progressive economists and political sections, that the National Food Security Act was passed, which brought 75 percent of the rural population and 50 percent of the urban population under the Public Distribution System. The Act also extended the purview of food security to include the school meal programmes and supplementary food schemes for pregnant and lactating women.

The role of the PDS proved to be crucial in cushioning the effects of the previous global food price crisis that followed the financial crisis in 2007-08. The wheat and rice prices did rise, but they were nothing in comparison to the international prices. The wheat prices in the period between 2005-2008 rose by only 21 percent in India as compared to 170 percent globally. In the same period the rice price in India grew by only 16 percent in sharp contrast to 230 percent internationally. [xv]

Some of the measures taken during the previous food crisis can be useful lessons for the current crisis too. These measures to restrict the spiraling effects of the global price rise of 2007-08 included the increased allocation of foodgrains under the Targeted Public Distribution System to protect the most vulnerable sections from food inflation. Over the years one of the functions of the PDS has been to stabilize domestic foodgrain prices, by releasing surplus grains through the Open Market Sale Scheme, which was also implemented during the past food price crisis. Further, there were efforts made to ensure that adequate stocks of foodgrains were available across the country and a zero duty private trade was opened up to import the deficit quantities of foodgrains. The Minimum Support Prices for wheat, rice were raised to encourage farmers to increase their production and higher public procurement in 2006-07 after a year of deficient production and market arrival.[xvi]

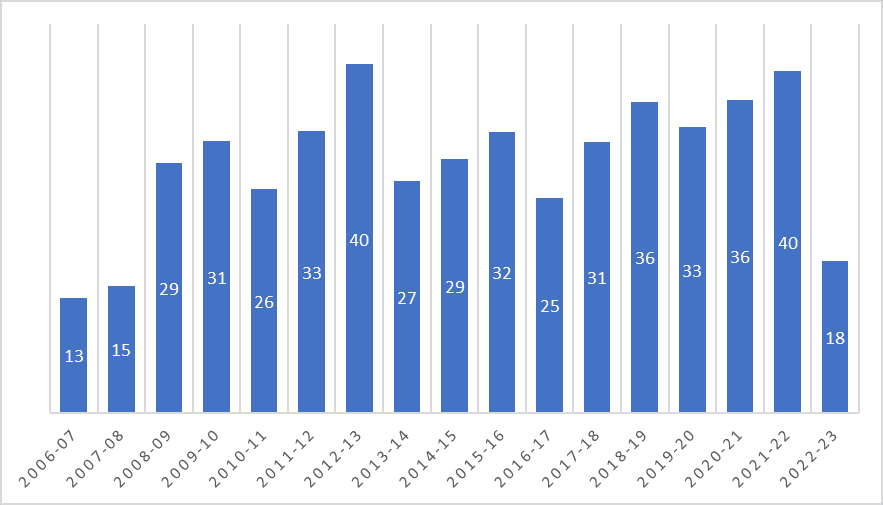

Despite the demonstrated role of the PDS in managing food crises and food security of the country, there have been increasing attacks on food subsidy and procurement since the present BJP government came to power in 2014. There was a fall in the share of procurement of foodgrains by the Food Corporation of India in the period between 2014-2019 (see Figure 4). It was only in 2020-21 and 2021-22 that there was an increase in the procurement levels owing to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Figure 4: Share of FCI Procurement of Wheat Production in Various Years

Source: Food Corporation of India

The three contentious Farm Laws brought by the central government in 2020 further spelt out its policy orientation towards the PDS. One of the major aims of the historic farmers’ movement was to point out the intentions of the farm laws to ultimately strangle the PDS by disbanding the public procurement system through weakening the government run agricultural markets in favour of big agri-businesses. The movement emphasized that the farm laws would be a threat to both farmers’ incomes as well as the country’s food security and detrimental for the majority of the hunger prone poor population.

Further, there has been a drastic cut in the food subsidy bill in this year’s budget, despite the fact that the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic have been accentuated by the global recessionary trends.[xvii] Additionally there has also been a reduction in the expenditure for procurement of foodgrains, which negates the opportunity for providing relief to farmers who have been suffering from rising cost of cultivation and crop losses, and creating any incentives to raise production.

The most recent controversy raked up by the government has been the touting of several welfare oriented schemes, including the food transfers under the PDS as ‘freebies’. This formulation obliterates the fundamental right to food which has been enshrined in the Indian Constitution through a protracted peoples’ movement, and the contribution of PDS in averting hunger, enhancing human development and country’s growth.[xviii]

Need for a Holistic Approach towards Food and Livelihood

It needs to be recognised that behind the present inflationary trend in food prices experienced in India, which have been an outcome of global prices, supply and weather shocks, there also lies a continuing condition of lack of adequate incomes and stunted consumption, especially in the countryside.[xix] The food price inflation is also more bitingly felt by the rural population due to the greater share of food in their consumption basket.

Therefore any meaningful approach towards tackling the food crisis also has to seek an adequate income for its farmers and factor their increasing losses accrued to climatic variabilities.[xx] Farmer organisations in the wake of the current wheat crisis, crop losses due to climatic variations and increased fertilizer and input costs leading to rise in cost of production had demanded a bonus of INR 500 per quintal of procurement.[xxi] However, the government failed to raise the Minimum Support Prices by any effective measure. The coalition of farmers’ organisations, Samyukt Kisan Morcha (United Farmers’ Movement), which spearheaded the farmers’ movement against the Farm Laws continue to demand for expansion of procurement and a legal right to remunerative prices and MSP.

Taking lessons from the previous food price crisis in 2007-08, it was emphasized especially for the developing countries that in order to avoid similar crises in the future, public funding for agriculture has to increase, support to small-scale farmers have to be raised for production of staple food crops, build national/regional food reserves and control over resources and services have to be ensured.[xxii] The present crisis too as discussed above reflects on the importance of public stockholding and farmers’ support for controlling widespread hunger and devastation.

However, this would need challenging the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and its Agreement on Agriculture (AoA), which has continued to evade any permanent solution for the issue of Public Stock Holding, Special Safeguard Mechanism and Special and Differential Treatment, matters of great concern for the food security and livelihood of small-holder farmers in developing countries.[xxiii]

But before taking on the battle abroad, the Indian government has to be answerable for the domestic policies it has been undertaking, which undermine the PDS and public support for its huge population of small and marginal farmers. It has to first get rid of its duplicity at home. Food security and self-sufficiency must be recentred in India’s agricultural policy.

[i] Press Information Bureau (2021), Fourth Advanced Estimate of principle crops released, Press Release, 11 August, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1744934

[ii] Athar, Uzmi (2022), “Experts link recent drop in wheat production to climate change, urge India to take it up in COP27”, Economic Times, 28 August, https://m.economictimes.com/news/economy/agriculture/experts-link-recent-drop-in-wheat-production-to-climate-change-urge-india-to-take-it-up-at-cop27/articleshow/93834002.cms

[iii] Das, Sandip (2022), “India Aims to export 10 million tonne of wheat worth $4 billion in 2022-23”, Financial Express, 4 April, https://www.financialexpress.com/economy/india-aims-to-export-10-million-tonne-of-wheat-worth-4-billion-in-2022-23/2480352/

[iv] Press Trust of India (2022), “India exported 1.8 million tonnes of wheat to several countries since ban: Food Secretary”, The Hindu, 26 June, https://www.thehindu.com/business/Economy/india-exported-18-million-tonnes-wheat-to-several-countries-since-ban-food-secretary/article65567118.ece

[v] Press Information Bureau (2021), Agri Export Policy, Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1697017#:~:text=Agri%20Export%20Policy&text=The%20Government%20introduced%20a%20comprehensive,exports%2C%20including%20focus%20on%20perishables.

[vi] PIB (2022), Surplus Overall Grain Availability in the country: Secretary, Food, 4 May, Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution, Government of India, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1822713

[vii] Hoskins, Peter (2022), “Ukraine war: Global wheat prices jump after India export ban”, BBC, 16 May, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-61461093

[viii] Press Trust of India (2022), “Govt bans export of wheat flour, maida, semolina to curb rising prices”, Business Standard, 28 August, https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/govt-bans-export-of-wheat-flour-maida-semolina-to-curb-rising-prices-122082701074_1.html#:~:text=In%20order%20to%20ensure%20food,the%20corresponding%20period%20in%202021.

[ix] Gupta, Aman (2022), “Only allocated rice in rations, people sell it to buy expensive wheat”, Down to Earth, 19 August, https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/agriculture/only-allocated-rice-in-rations-people-sell-it-to-buy-expensive-wheat-84407

[x] Press Trust of India (2022), “Kharif sowing nears to end; paddy acreage down by 5.51%”, The Hindu, 23 September, https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/agriculture/kharif-sowing-nears-to-end-paddy-acreage-down-by-551/article65926319.ece

[xi] Ghosh, Saptaparno (2022), “Explained-the ban on the export of broken rice”, The Hindu, 18 September, https://www.thehindu.com/business/agri-business/explained-the-ban-on-the-export-of-broken-rice/article65906053.ece

[xii] Sen, Amartya (1981), Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation, Clarendon Press, Oxford

[xiii] Chari, Mridula (2021), “Famished”, Fifty Two, https://fiftytwo.in/story/famished/

[xiv] Swaminathan, Madhura (2000), Weakening Welfare, Left Word, New Delhi

[xv] Dev, Mahendra (2009), Rising Food Prices and Financial Crisis in India, UNICEF Social Policy Programme, https://www.ids.ac.uk/download.php?file=files/dmfile/RisingFoodPricesinIndiaUNICEFFinal.pdf

[xvi] Government of India (2007), Economic Survey 2006-07, https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget_archive/es2006-07/price.htm

[xvii] Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (2022), In search of inclusive recovery: an analysis of Union Budget 2022-23, https://www.cbgaindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/In-Search-of-Inclusive-Recovery-An-Analysis-of-Union-Budget-2022-23.pdf

[xviii] Sinha, Dipa (2022), “Making sense of the ‘freebies’ issue”, The Hindu, 3 August, https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/making-sense-of-the-freebies-issue/article65717382.ece

[xix] Samridhi, Agarwal and Damodaran, Harish (2022), “The Return of Food Inflation: Why It’s Different This Time”, Policy Engagements and Blogs, Centre for Policy Research, https://cprindia.org/the-return-of-food-inflation-why-its-different-this-time/

[xx] Economists such as Abhijit Sen (2016) have pointed to the increasing need to ‘devise safety nets to cope with risks whether from markets or climate’. “Some Reflections on Agrarian Prospects”, Economic and Political Weekly, vol 51, no 8

[xxi] All India Kisan Sabha (2022), “AIKS demands full procurement and bonus of Rs 500 per quintal of wheat”, 18 May, http://kisansabha.org/aiks/press-releases/aiks-demands-full-procurement-and-bonus-of-rs-500-per-quintal-for-wheat/

[xxii] Mittal, Anuradha (2019), The 2008 Food Price Crisis: Rethinking Food Security Policies, G 24 Discussion Paper Series, No 56, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/gdsmdpg2420093_en.pdf

[xxiii] Basu, Ranjini and Guttal, Shalmali (2022), Agricultural Negotiations at WTO: No Real Solutions in Sight, Focus on the Global South, https://focusweb.org/agriculture-negotiations-at-wtomc12/