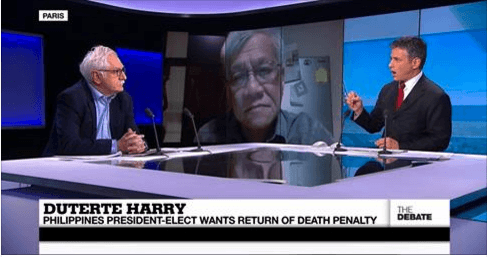

By Walden Bello

This is an extract from a longer article by Walden Bello titled, “An administration in search of an opposition,” published by Rappler on 10 July 2016. To read the complete article, please go to: http://www.rappler.com/thought-leaders/139170-administration-in-search-opposition

Fundamental Rights and Positive Rights

When he first signaled his intention to run for the presidency last year, I said that Duterte’s candidacy would be good for democracy because it would force liberals and progressives to defend a proposition that they had long taken for granted: that human rights and due process are core values of Philippine society.

Let us now address this urgent task.

The right to life, right to freedom, right to be free from discrimination, and right to due process have often been called fundamental rights because they assert the intrinsic value of each person’s existence and underline that this value is not bestowed by the state or society. They are also often called “negative” rights or “inalienable” rights to stress that other individuals, corporate bodies, or the state have no right to take them away or violate them.

What have now come to be known as “positive rights” such as the right to be free from poverty, the right to a status of economic equality with others, and the right to a life with dignity are those rights that promote the attainment of conditions that allow the individual or group to develop fully as a human being. Positive rights—sometimes referred to as social, economic, and cultural rights—build on negative or fundamental rights. The recognition and institutionalization of fundamental rights may have been historically prior to the recognition and achievement of positive rights but the latter are necessary extensions of the former. Rights, in short, are indivisible, and positive rights have a fragile foundation in a state where the basic right to life is negated by leaders who claim to be promoting them.

Liberal Democracy vs Authoritarian Rule

One of the key functions of the state is to secure the life and limbs of its citizens, but this must be accomplished while respecting the full range of rights of its citizens. There is a necessary tension between not violating individual rights and achieving security and political order. This healthy tension is what distinguishes the liberal democratic or social democratic state from the authoritarian, fascist, Stalinist, or ISIS state.

To progressives and liberals, recognition and respect for human, civil, political, social, economic, and cultural rights have been a fundamental thrust in the evolution of the Philippine polity, a process that has been influenced by landmark events in the history of democracy such as the French Revolution and the later struggles against colonialism, fascism, and Stalinism. Individual rights have been won in interconnected global struggles against ruling classes, imperial oppressors, corporations, and bureaucratic and military elites. This historical process has produced polities called liberal democracies and social democracies, the latter being distinguished by their greater stress on the achievement of the full range of positive rights, including universal social protection.

However, one must acknowledge that there has been a counter-thrust, one that has periodically emerged to challenge the primacy of individual and human rights. This perspective places the state as the authority or arbiter of what “rights” the individual can enjoy, subordinates the welfare of the individual citizen to the security or needs of the state, and says that due process is principally one determined by the needs of the state and not by respect for the rights and welfare of the individual. This historical counter-thrust became dominant during the martial law period from 1972 to 1986 and it threatens to become dominant today, with support from a significant part of the citizenry.

The Perils of Dutertismo

Currently, President Duterte embodies the view that refuses to recognize the universality of rights and denies due process to certain classes of people in the interest of combating crime and corruption. The majority of those who voted for him agree with his stance. They form the social base of Dutertismo, a movement based on mass support for a leader who personifies the illiberal, extreme measures they feel are necessary to deal with crime, corruption, and other social problems.

At the risk of repeating ourselves, let us make three points with respect to this trend.

First, we do not question the goal of fighting crime. Indeed, we support it. But it cannot be achieved by trampling on human rights. No one has the right to take life except in the very special circumstance and in a very clear case of self-defense. Everyone is entitled to the enjoyment of those rights and their protection by the state. And if these rights must be limited for the greater good, then there must be a legally sanctioned process to determine this. Wrongdoers must certainly be meted punishment, but even wrongdoers have rights and are entitled to due process.

Second, denying some classes of people these rights, as Duterte does, puts all of us on the slippery slope that could end up extending this denial to other groups, like one’s political enemies or people that “disrupt” public order, like anti-government demonstrators or people on strike for better pay. In this connection, remember that candidate Duterte threatened to kill workers who stood in the way of his economic development plans and made the blanket judgment that all journalists who had been assassinated were corrupt and deserved to be eliminated. That was no slip of the tongue.

Third, rights are indivisible. Measures that purportedly promote positive rights and advance the economic and social welfare of citizens rest on a fragile basis and can easily be taken back if they are not recognized as stemming from and resting on the basic right to life. Upholding positive rights while negating fundamental rights involves one not only in a logical but in a very real contradiction. To say I will liberate you from exploitation but hold your life hostage to your “good” behavior involves one in a contradiction that is ultimately unsustainable; this is the contradiction that unraveled the Stalinist socialist states of Eastern Europe.