Hopes that the so-called COP 20 (Conference of Parties 20) of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) would deliver an outcome that would reverse the momentum towards climate catastrophe were dashed by an event that was announced three weeks before the delegates assembled in Lima, Peru: the so-called US-China climate deal.

Breakthrough?

Said to be the product of nine months of secret talks, the agreement between the country that has contributed most to the accumulation of greenhouse gases and the nation that is currently the world’s lead carbon emitter was lauded in many quarters as a “breakthrough.”

Climate skeptics to the end, Republicans in the United States predictably criticized the deal as sacrificing US jobs and growth and skewed in favor of China. But the deal evoked a fair share of criticism from experienced climate observers as well.

The key provision triggering dismay was the agreement that China would not begin reducing its emissions until 2030. As for the US’s commitment to bring down emissions by 26 to 28 per cent from 2005 levels, the cut, while significant, will not be enough to derail the planet from the track towards a 2 degrees centigrade + world by the turn of the century. For the US cuts to begin to make even the slightest dent, the base line should have been 1990 levels, which have long served as the universally agreed standard.

Moreover, the critics point out the deal does not have the force of law. This is crucial since mere executive action will not be sufficient to accomplish the cuts that President Obama’s negotiators promised, and the incoming Republican-controlled Congress is not likely to legislate the powers necessary for the Democratic president to deliver on his promise to the Chinese.

Obama and Xi’s Message to Lima

It was, however, the message the agreement delivered to the negotiators from over 190 countries assembling in Lima during the first two weeks of December that proved most disconcerting.

Essentially what Obama and Chinese Premier Xi Jinping were telling the delegates was, “We’re not going to subject what we decide to agree on to a multilateral process. Moreover, what we offer in terms of emissions cuts will not be determined by some objective assessment of what we should be offering, guided by the principles of equity and ‘common but differentiated responsibilities,’ but by what we ourselves decide to place on the table. Also, compliance will be voluntary, not something mandatory and with the force of law.”

The US-China accord was, of course, just one of the elements that influenced the outcome of the negotiations in Lima. However, it was decisive. For one, the example it offered of a unilateral and non-transparent process of setting non-mandatory emissions cuts meant that hopes for setting up a more rigorous climate regime based on mandatory emissions during the December 2015 UNFCCC convention in Paris were dashed. Moreover, faced with intransigence on the part of the developed countries, the deal provided the formula for a face-saving retreat by developing countries from their tough stand that it should be the rich industrialized countries that should bear the burden of emissions cuts–a stance that was encapsulated in the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities.” The phrase that broke the deadlock on this front was copy-pasted from the US-China accord, which modified the principle to “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in light of different national circumstances.” For the rich industrialized countries (and the big emerging economies as well) this blurring of the lines between developed and developing countries was a major victory since it meant that dealing with the volume of greenhouse gases that have accumulated owing largely to their production and consumption will now be every country’s responsibility. The developed countries’ positive reception is understandable since saying something is everyone’s responsibility really means it is no one’s responsibility.

With China promoting a redefinition of the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities out of self interest, many developing countries felt they had been left with no option but to sign on to the “Lima Call for Climate Action.” Not surprisingly, many felt they were left high and dry by China’s climate “pivot,” as some negotiators termed it.

To Lidy Nacpil of the climate advocacy organization Jubilee South, the Lima outcome is “another fatal step in the strategic retreat from the Kyoto Protocol,” which had bound the developed countries to mandatory emissions cuts. Nacpil and other climate activists see the Lima declaration as setting weak foundations for the new climate regime that will replace the Kyoto Protocol, which is supposed to be inaugurated in Paris in December 2015. Making up centerpiece of the coming regime will be the so-called “Intended Nationally Determined Contributions” (INDCs), or the voluntarily offered emissions cuts that will be made by countries in lieu of mandatory pledges.

Flaws of the Lima Declaration

Perhaps the most comprehensive and incisive analysis of the Lima outcome comes from Pablo Solon, executive director of Bangkok-based analysis and advocacy institute Focus on the Global South. Formerly Bolivia’s ambassador to the United Nations, Solon says that the main flaws of the Lima agreement are the following;

– It mentions “loss and damage” in the preamble, but fails to say anything more definitive on how compensation will be paid to countries and communities now suffering from the emissions caused by the climate-polluting countries.

– The text makes no mention of the need to change current patterns of production and consumption. “The different proposals focus on reductions of emissions produced in a country, and not the emissions consumed in a country,” Solon asserts. He points out that one-third of CO2e emissions associated with the goods and services consumed in developed countries are being emitted outside the borders of those nations, mostly in the developing world. “It is not enough to reduce emissions in developed countries if they do not also reduce their consumption of products that generate CO2e emissions in other parts of the world.”

– The text is quiet on the need to keep 75% or 80% of known fossil fuel reserves under the ground, something that must be done if CO2 emissions are to be limited to a pathway of less than 1.5 or 2º C. “Indeed, In the 1,892 lines of the text,” he points out, “there is only one mention of ‘fossil fuels’– regarding a proposal to phase out ‘fossil fuel subsidies’ – and there are only general mentions of ‘reductions in high-carbon investments.’

– The declaration avoids identifying the sources of the US$100 billion Green Climate Fund that would support the adaptation efforts of the global South.

Solon reserves his strongest criticism for the provisions relating to mitigation, or emissions reduction. The pillar of the coming regime will be the voluntarily offered pledges to cut called “Intended Nationally Determined Contributions” (INDCs). Solon points out that there is no proposal for a strong compliance mechanism to ensure that countries live up to their INDC’s. “What happens if a big polluter fails to cut emissions on time and damages a vulnerable country is not considered in the text,” he asks. “No mention is made of a mechanism to demand and sanction governments and corporations for their inaction. All the options in the text consider only processes of review or assessment. A climate agreement without a strong compliance mechanism is just a political declaration.”

Solon’s concern is a matter of great importance to developing countries since over the last few years, Canada, Russia, and New Zealand have withdrawn from the Kyoto Protocol, and Australia and Japan have failed to reached their legally binding targets under the convention. Yet these countries have not been sanctioned.

To Solon, what is most damaging, however, is the watering down of the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” to “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in light of different national circumstances,” as a result of joint lobbying by chief US negotiator Todd Stern and his Chinese counterpart Xie Zhen Hua for the convention to adopt the reformulation of the principle in the US-China agreement. In recent years, many poor countries and civil society organizations have insisted that developed countries, which have, historically, contributed the most to accumulated greenhouse gases, as well as the big emerging economies, which are currently becoming the biggest emitters, should be principally responsible for taking on the burden of climate emissions. The new formulation, according to Solon, “will dilute more and more the historical responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions of developed and emerging economies.” The big losers are the poor underdeveloped countries, and the big winners are China and the United States, which, according to Solon, now “have an agreement to erase their responsibility for the climate chaos they created.”

The Washington-Beijing Climate Axis

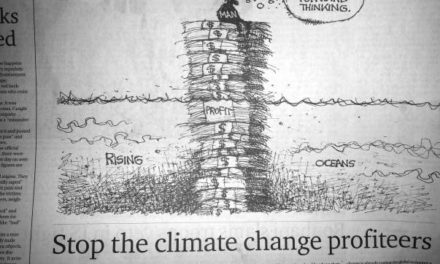

In the past, the US and China used each other’s intransigence as an excuse to avoid making cuts in their carbon emissions. The world was becoming weary of this game, forcing the two to drop their pretense of opposing each other in favor of a show of cooperation. With their climate agreement and the Lima Declaration that they played a central role in crafting, the two biggest emitters have set the parameters of global climate action. These are parameters that all but ensure that the world will be on way to the 4 to 6 degrees centigrade plus world that will be our generation’s catastrophic legacy to our descendants.

Walden Bello is a member of the House of Representatives of the Philippines and a long-time climate activist.