Landowners resorting to “legal harassment” or the act of ling numerous criminal cases to weaken dissenting farmers’ groups are common cases in agrarian disputes in the Philippines.

Rolando “Ka Rolly” Martinez is the current barangay (village) captain of Sumalo, a small village in the municipality of Hermosa, Bataan province. Besides his usual tasks as village chief, he also leads a small farmers’ organization, the “Sanamabasu,” in an ongoing struggle against a land developer, the Riverforest Development Corporation, for their claims on a 213-hectare farmland. For more than 20 years, Ka Rolly and the Sanamabasu resiliently stood against the constant harassments and intimidations done by the armed guards of Riverforest while sustaining a protracted agrarian reform case now lodged in the Supreme Court.

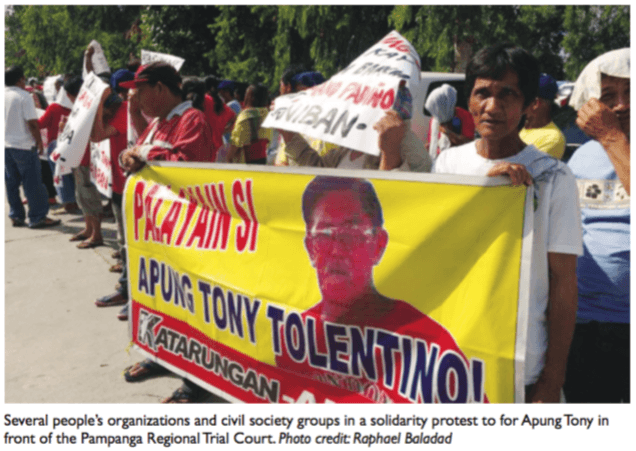

Another village chief,“ApungTony” Tolentino, is also a farmer leader. Elected as barangay captain in 2013, his primary tasks included maintaining peace and security in the remote village of Hacienda Dolores, in the municipality of Porac, Province of Pampanga.As the president of a farmers’ organization called “Aniban,” he fought against the conversion of a 761-hectare farmland into an eco-tourism area by the company Leonio Land Holdings.The farmers of Hacienda Dolores had also held out against harassments and intimidations made by the developers’ armed guards since the filing of an agrarian reform case in 2005.

In 2009, criminal cases were led against Ka Rolly and 27 other farmers of Sanamabasu by the armed guards of Riverforest. Charges such as grave coercion, destruction of private property, and grave threats were slammed against the farmers who had resisted the land enclosures being installed by Riverforest. Led by Ka Rolly, the farmers had formed blockades to prevent construction supply trucks from entering their farmlands.These actions significantly stalled, but failed to stop the entire fencing operation of the land. Eventually, poverty ensued in the area as farmers were unable to ingress and tend to their farms and livestock, or leave to bring agricultural produce to the market. Living conditions worsened when Ka Rolly and the farmers lead to go to court hearing for the criminal charges. Eighteen of these farmers are mothers, now with very little income to feed their families.

In Hacienda Dolores, the petition for agrarian reform coverage escalated tensions. Leonio Land became more aggressive in clearing out the area, but the farmers steadily resisted, even amidst death threats, forcible evictions, and land enclosures.The struggle however peaked with the death of Armand Padino in 2014, in a standoff against armed guards who were mobilized to prevent any harvest within the disputed farmlands. To disperse the conflict, the armed guards opened re, killing Padino, a farmer, and wounding several others. As the village chief, Apung Tony and his men responded to the situation, arresting one of the gunmen who ed in a motorcycle. Apung Tony kept the gunman in the village hall for further investigation. Held only in a small room, the gunman managed to escape days thereafter. In less than three months after the incident, Apung Tony was arrested by the local police for non-bailable crimes such as kidnapping, carnapping, illegal detention, and frustrated murder.

Both Ka Rolly and Apung Tony stood as champions of peasant struggles in their respective areas; undertaking almost all of the legwork required to expedite or sustain the land cases still pending in higher courts as well as taking the brunt of the harassments and intimidations done

to the farmers. Land grabbers can attempt to crush the heads of a movement and lower its morale, but these often potentially give way to stronger resistance or may incur public disgust. Thus, discrediting the legitimacy of a movement by condemning key people has become a better option to immobilize them by utilizing socially accepted or legal mechanisms, and this also prevents further popular support.

The wariness and doubt that resulted from the criminal cases led against Ka Rolly and Apung Tony greatly affected the cohesiveness of their organizations. Morale hit its lowest and some farmers eventually gave in and sold their claims to developers. Others ed out of sheer terror from getting criminalized or killed. Some local government of cials withdrew their support/assistance simply because the farmers’ struggles had been deemed illegal.

The criminal cases were tough for Samabasu farmers who were regularly summoned to appear in court hearings, sometimes held outside the municipality. On top of the criminal cases, administrative cases were also led at the Of ce of the Ombudsman against Ka Rolly and other village of cials who supported him.As if a single criminal case were not enough, some farmers had over nine cases in their names.The local court even upheld a grave coercion and grave threats charges led against a 77-year old woman by an armed security personnel.

Menelao “Ka Melon” Barcia, became Aniban’s leader in the absence of Apung Tony, picking up the work for the agrarian case and at the same time taking care of the legal pleadings for the latter’s acquittal. Less than two months after Apung Tony had been incarcerated, Ka Melon was ambushed by motorcycle-riding gunmen as he was driving home with his wife. He died on the spot while his wife was seriously injured. He held in his hands documents from their lawyer arguing against the arrest of Apung Tony which became spattered with blood.

During a solidarity protest in the third hearing for Apung Tony’s case last June 2015, one of the farmers exclaimed,“before, these developers were only interested in taking our lands and our livelihood, but now they are keen on destroying our lives.” But the protest did not lead to their leader’s acquittal.Tears rolled down Apung Tony’s cheeks while his lawyer and several family members comforted him. He was cuffed and taken back to the city jail.

Last June 2016, Ka Rolly and the 27 farmers of Sanamabasu were again summoned by the local court for the resolution of the criminal cases against them. On his way to the courthouse, Ka Rolly lamented, “We have had to stomach a lot; from the destruction of crops and livestock to death threats. But out of all that we have faced, the hardest to accept is the possibility of criminalizing those who fought dearly for their right to the land.” Waiting in the courtroom in the longest two hours of their lives, the Judge nally stepped in and handed down the decision: dismissal of all criminal cases led due to the lack of merit.

With renewed passion, Ka Rolly and Sanamabasu continue their struggle for land, believing that justice will prevail.Today, they are active in government-led consultations for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and other People Working in Rural Areas, pushing for provisions against the criminalization of peasants and farmers’ struggles and the perpetual protection of farmlands against land conversions Apung Tony is still in jail. He was however granted permission to undergo medical treatment due to his deteriorating health.With support from several civil society groups and the church, the farmers of Aniban continue their struggle for land, while fervently seeking Apung Tony’s release.

Criminalizing social struggles or dissent contradicts the ideals of justice anchored in the promotion of human rights. In the essence of democracy, people should have the right to struggle, to push for reforms without fear of condemnation from the rule of law.Thus, each case led against farmers struggling to protect their rights should merit an outrage from the public because it attacks the basic freedoms the law should fundamentally protect.The experiences of Apung Tony, Ka Rolly, and hundreds of other criminalized farmers are blatant examples on how the law can be circumvented, twisted or manipulated to serve the interests of certain few—which should be cause for the judiciary to re ect on their capacity to be detached from external in uence, in entertaining cases and rendering decisions.