The military coup in Thailand a week ago marked the second high profile collapse of a democracy in the developing world in the last seven years. The first was the coup in Pakistan in October 1999 that brought General Pervez Musharraf to power. Like the coup in Thailand, that coup was popular with the middle class. As in Thailand, the military was expected to vacate power soon after it ousted Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. Six years later, Musharaff and the army are still in power.

By Walden Bello*

(Summary: Even before Thaksin, Thai democracy was already in severe crisis owing to a succession of elected but do-nothing or exceedingly corrupt regimes since 1992. Its legitimacy was eroded even further by the IMF, which for all intents and purposes ran the country, with no accountability, for four years, from 1997 to 2001, and imposed a program that brought great hardship to the majority. Thaksin stoked this disaffection with the IMF and the political system to create a majority coalition that allowed him to violate constitutional constraints and infringe on democratic freedoms, while enabling him to use the state as a mechanism of private capital accumulation in an unparalleled fashion. This led to the middle-class based, politically diverse opposition that sought to oust him by relying not on electoral democracy but on people power, the democracy of the street. The tide turned against Thaksin, and in the last few months, he not only lost moral legitimacy but a great deal of political power. Thai politics was not gridlocked, and the democracy movement was about to launch the final phase to drive Thaksin out when the military intervened. Though it is for the moment popular among Bangkokians, the coup will eventually prove to be a cure worse than the disease. Civil society cannot condone the coup, and it must move to make its presence felt in the current institutional vacuum to counter the moves of the newly assertive Old Right. But more than this, it must elaborate an alternative political program that will win the critical or hegemonic mass that would put democracy on firm foundations.)

Democracy on the Ropes

It is now claimed in some quarters that Thaksin Shinawatra undermined the democratic regime that came into being after the people’s power uprising in May 1992. True, but Thai democracy was in bad shape before Thaksin came to power in January 2001. The first Chuan Leekpai government from 1992 to 1995 was marked by the absence of even the slightest effort at social reform. The government of former provincial businessman Banharn Silipa-Archa, from 1995 to 1996, was described as “a semi-kleptocratic administration where coalition partners were paid to stay sweet, just like he used to buy public works contracts.” Then followed, in 1996-97, the government of Chavalit Yongchaiyudh, a former general, which was based on an alliance among big business elites, provincial bosses, and local godfathers. Relatively free elections were held, but they served mainly to determine which coalition of elites would have its turn at using government as a mechanism of private capital accumulation.

Not surprisingly, the massive corruption, especially under Banharn and Chavalit, repelled the Bangkok middle class, and the urban and rural poor did not see the advent of democracy marking a change in their lives.

Thailand under IMF Rule

Democracy suffered a further blow in 1997-2001 following the Asian financial crisis. This time it was not the local elites that were the culprit. It was the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which pressured the Chavalit government, then the second Chuan government to adopt a very severe reform program that consisted of radically cutting expenditures, decreeing many corporations bankrupt, liberalizing foreign investment laws, and privatizing state enterprises. The IMF assembled a $72 billion rescue fund, but it was money that was spent not to save the local economy but to enable the government to pay off the foreign creditors of the country. When the Chavalit government hesitated to adopt these measures, the IMF pressed for a change in government. The second Chuan government complied fully with the Fund, and for the next three years Thailand had a government that was accountable not to the people but to a foreign institution. Not surprisingly, the government lost much of its credibility as the country plunged into recession and one million Thais fell under the poverty line. Meanwhile the US Trade Representative told the US Congress that the Thai government’s “commitments to restructure public enterprises and accelerate privatization of certain key sectors-including energy, transportation, utilities, and communications-[are expected] to create new business opportunities for US firms.”

The IMF, in short, contributed greatly to sapping the legitimacy of Thailand’s fledgling democracy, and, in this connection, this was not the only instance where the Fund contributed to eroding the credibility of a government, especially among the poor. If there is today a pattern reversing so-called “Third Wave” of democratization that took off as a trend in the developing world since the mid-seventies, the IMF-supported of course by the US government-is part of the answer. An IMF program requiring steep rises in transport costs destroyed the last ounce of legitimacy of Venezuelan democracy in 1989 and plunged the country into the spontaneous rising known as the “Caracazo.” Earlier, in 1987, the IMF forced the new democratic Aquino government in the Philippines to adopt a national economic program prioritizing debt repayment over development, pushing the Philippines into a period of stagnation, rising poverty, and rising inequality that saw, among other things, the squandering of much of the legitimacy of the democracy that succeeded Marcos. Also, a key contributor to the unraveling of Pakistan’s democracy were the structural adjustment programs that the IMF and the World Bank got both the government of Benazir Bhutto and that of her rival Nawaz Sharif to impose on the country. Since parliamentary democracy became associated with a rise in poverty and economic stagnation, it is not surprising that the Musahrraf coup was viewed with relief by most Pakistanis, from both the middle classes and the working masses.

The Thaksin Years: Monopoly Capitalism cum Populism

Returning to Thailand, it was a severely compromised democracy that Thaksin stepped into in 2001 after running and winning on an anti-IMF platform. In his first year in office, Thaksin inaugurated three heavy spending programs that directly contradicted the IMF: a moratorium on farmers’ existing debt along with facilitating new credit for them, medical treatment for all at only 30 baht or less than a dollar per illness, and a one million baht fund for every district to invest as it saw fit. These policies did not bring on the inflationary crisis that the IMF and conservative local economists expected. Instead they buoyed the economy and cemented Thaksin’s massive support among the rural and urban poor.

This was the “good”side of Thaksin. The problem was that, having secured the majority with these programs and with practices that analysts Alec and Chanida Bamford called “neofeudal patronage,” he began to subvert freedom of the press, use control of government to add to his wealth or ease restrictions on his businesses and those of his cronies, buy allies, and buy off opponents. His war on drugs, using his favorite agency, the police, resulted in the loss of over 2,500 lives; this bothered human rights activists but the campaign was popular with the majority. He also assumed a hardline, purely punitive, policy toward the Muslim insurgency in the three southern provinces that merely worsened the situation there. His championing of a free trade agreement with the US created an opposition coalition of activists and threatened agricultural and industrial interests. High-handed, arrogant, unwilling to listen, and vindictive, he was his own worst enemy.

Thaksin appeared to have created the formula for a long stay in power, supported by an electoral majority, when he overreached. In January, his family sold their controlling stake in telecoms conglomerate Shin Corp. for $1.87 billion to a Singapore government front called Temasek Holdings. Before the sale, Thaksin had made sure the Revenue Department would interpret or modify the rules to exempt him from paying taxes. This brought the Bangkok middle class to the streets to demand his ouster in a movement that bore a striking resemblance to the so-called “People Power Uprising” that overthrew Joseph Estrada in the Philippines in January 2001.

To resolve the polarization, Thaksin dissolved Parliament and called for elections, knowing that he would win elections handily, as his coalition had in 2001 and in 2005. The April 2 elections were held, Thaksin’s coalition won 57 per cent of the vote, but they were boycotted by the Opposition, leading to an Opposition-less Parliament. After a not-too-veiled suggestion by the revered King Bhumibol, the Supreme Court found the elections in violation of the Constitution and ordered them held once more. Thaksin resigned as Prime Minister and said he would be a caretaker PM till after new elections were held.

It is useful to pause here and note certain dimensions of the Thai conflict:

-

It pitted, in general terms, the urban and rural classes-the majority-against the middle classes, meaning mainly the Bangkok middle class.

-

It witnessed, as a principle of succession, a conflict between representative democracy via elections and the direct democracy of the streets.

-

It involved a split between the two principles that are united in the system of liberal democracy-liberalism and democracy. Invoking the legacy of liberalism, the people in the streets sought to remove Thaksin for his violations of human and civil rights and his arbitrary rule, while Thaksin’s supporters sought to keep him in power by appealing to the basic principle of a democracy–that is, the rule of the majority. The anti-Thaksin forces, however, claimed that Thaksin’s majority rule fit the phenomenon that John Stuart Mill described as the “tyranny of the majority” that rested greatly on buying off the people.

Polarization but not Gridlock

It is critical to point out that prior to the coup, the country was not in gridlock. Certainly, it was far from descending into civil war. More important, the moral tide had turned against Thaksin, and his resigning as prime minister was a recognition of this. He had lost control, criticism of him was widespread in a media that was once tame, and the pressure was on for him to resign before the next elections, originally scheduled for October 15 but rescheduled for November. On Thursday, the day after the coup, the People’s Alliance for Democracy had planned to stage a mass rally to begin the final push against Thaksin from the streets.

This was democracy in action, with all its rough and tumble and the rambunctious efforts to resolve conflicting principles. Of course, the outcome was not guaranteed, nor was violence out of the question, but indeterminacy and prolonged resolution of disputes are part and parcel of the risks that come with democracy. Thais were wrestling to resolve the question of political succession through democratic, civilian methods. The seeming chaos of it all was a part of the growing pains of a democracy. And it seemed like “people power” or the democracy of the streets would, as in the people’s uprising of May 1992, successfully determine political succession, creating an important precedent in democratic practice. Direct democracy not only had relevance for the political succession; it was reinvigorating and renewing the democratic practice and democratic spirit.

That is the vibrant democratic process that the military coup cut short. This move, everybody agrees, was unconstitutional, illegal, and undemocratic. Many say, however, that yes, it is all this, but it is popular and it is valid because it ended a crisis.

Cure Worse than Disease

This is questionable. This coup may have temporarily ended the crisis but at the pain of provoking a much deeper one, for several reasons:

-

Thaksin’s mass base, that is the poor and underprivileged, will be deeply alienated from successor regimes, viewing these post-coup regimes as possessing little democratic legitimacy.

-

The military has reasserted its traditional self-defined role as the “arbiter” of Thai politics, and this coup had as much to do with reasserting this role-which had been defined as illegitimate over the last 14 years-as with the current political crisis.

-

There has emerged a dangerous informal institutional axis that would subvert future democratic arrangements between the military and the Palace’s Privy Council, one of the few national political institutions that was not eliminated by military decree. This is, not surprisingly, given the fact that the Council is headed by a retired military strongman, Gen. Prem Tinsulanonda. Indeed, there is strong suspicion that Gen. Prem had more than just a neutral role in the affair as he had days before the coup told the military that their loyalty was principally “to the Nation and the King.”

-

The one really popularly drawn up constitution, the 1997 Constitution, has been abolished by military fiat. This constitution, approved after consultation with civil society, placed many controls on the exercise of parliamentary and executive power and on the behavior of politicians and bureaucrats. Ironically, the anti-Thaksin coup leaders, for all their rhetoric about “restoring democracy,” simply delivered the coup de grace to a very democratic document that Thaksin had systematically subverted.

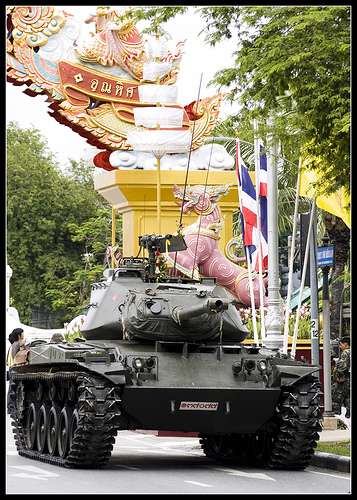

Some people say that coup leader Army Chief Gen. Sondhi Boonyaratkalin is sanguine about stepping aside. But personal predilections are no match for institutional interests. More than any other military in Southeast Asia, the Thai military has had a propensity for intervening in the political process, having launched some 18 military coups since 1932. Thai military men have an ingrained institutional contempt for civilian politicians, regarding them as blundering fools. The generals have often promised to return to civilian rule after a coup, but proceeded to rule directly or indirectly through military-appointed civilians. Gen. Sondhi’s words must be taken with the same seriousness as his assurance days before the takeover that military coups “were a thing of the past.”

Already, the generals have drafted an interim constitution that makes them “advisers” to an interim civilian government. Indeed, their circle has been joined by key authoritarian figures who wield power independently of them. There are said to be two prime candidates for premier position, and one of them, Surayud Chulanont, is a former Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces. The other is a civilian. That is not necessarily a virtue, for most civilian prime ministers appointed by the military have been weak politicians, whose tenures were marked by responsiveness to their military or authoritarian overseers. Anand Panyarachun, who was appointed prime minister after a military coup in 1991, was a notable exception in this regard. The civlian being eyed by the generals is most likely to fit the mold of a pliable tool rather than an independent leader like Anand. Supachai Panitchpakdi was seen as a weak Director General of the World Trade Organization, and one, moreover, who was overly responsive to the developed country agenda rather than to the interests of developing countries. More directly relevant is the fact that he was, in 1997-98, deputy premier in the Second Chuan Government that followed to a “t” the IMF program that proved so devastating for the country. At the time, he admitted in an interview: “We have lost our autonomy, our ability to deterine our macroeconomic policy. This is unfortunate.” Such a record does not inspire confidence that he is a person that can stand up to the military and other power centers in the country.

Where to Go?

Thailand today is at an institutional vacuum that is fast being filled by the old conservative (as opposed to populist) Right. But the final outcome is not determined. A great deal depends on Thailand’s increasingly mobilized civil society. For the people’s mass movement that was deprived of its opportunity to replace Thaksin through the methods of direct democracy, it seems essential, first of all, to stand on principle and condemn the coup as a return to a Jurassic past that cannot be condoned. There can be no if’s nor but’s on this issue. Some activists say that beyond this, the movement must insist that the 1997 Constitution remains in force. They also propose the setting up of a People’s Interim Council, with many of its leaders drawn from the People’s Alliance for Democracy, that would, among other things, organize new elections very quickly-in short, a system of “parallel power.” Though important, these are short term or medium term measures. Of greatest importance is whether popular leaders will be able to formulate a truly transformative political program that will bridge the gap between the middle-class based people’s power movement and the alienated lower classes that formed the electoral base of the deposed regime. Such an alliance would set democracy in Thailand on truly firm foundations. The question is: will Thai civil society rise to this historic challenge?

*Professor of Sociology at the University of the Philippines (Diliman) and author of ‘A Siamese Tragedy: Development and Disintegration in Modern Thailand’ (London: Zed, 1998).