Read the rest of the series at focusweb.org/tag/kaa70.

by Anisa Widyasari

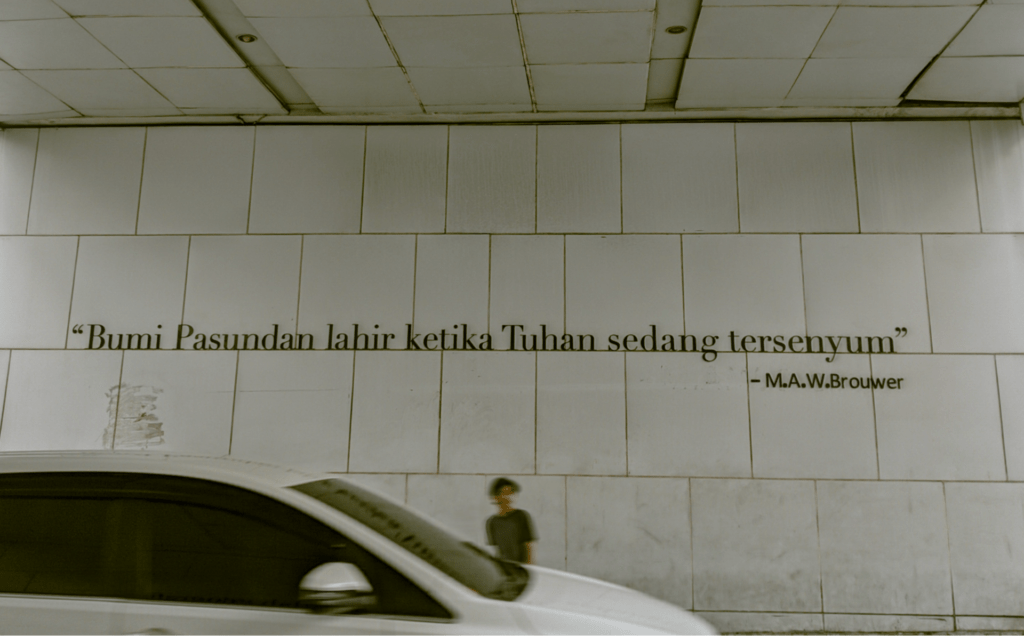

Right in the middle of one of the busiest streets in the city, on the wall of a pedestrian bridge of the Asia-Africa street, just a stone’s throw from the historic venue of the Asia-Africa Conference (Konferensi Asia Afrika in Bahasa Indonesia, commonly referred to as KAA) in 1955, is engraved a sentence that captures the essence of the city of Bandung in one phrase:

“Bumi Pasundan lahir ketika Tuhan sedang tersenyum.” The land of Pasundan was created when God was smiling – MAW Brouwer

The quote from MAW Brouwer is on the pedestrian bridge wall on the Asia-Afrika street. The street, previously known as Groote Postweg (in English: the Great Post Road), was named to honor the Asia-Africa Conference. Wikimedia Commons.

The quote from Martinus Antonius Wesselinus Brouwer[1], a Dutch-born writer and academic who spent most of his time in Indonesia, is not just a beautiful string of words, but also a reflection of how Bandung has long been seen as a charming city—for its breathtaking scenery as a city surrounded by mountains with its chilly breezes in the morning and warm sunshine during the day, and also for its fiery spirit that makes it a creative hub—the same spirit which led its people to set the city ablaze in defiance of colonial rule.

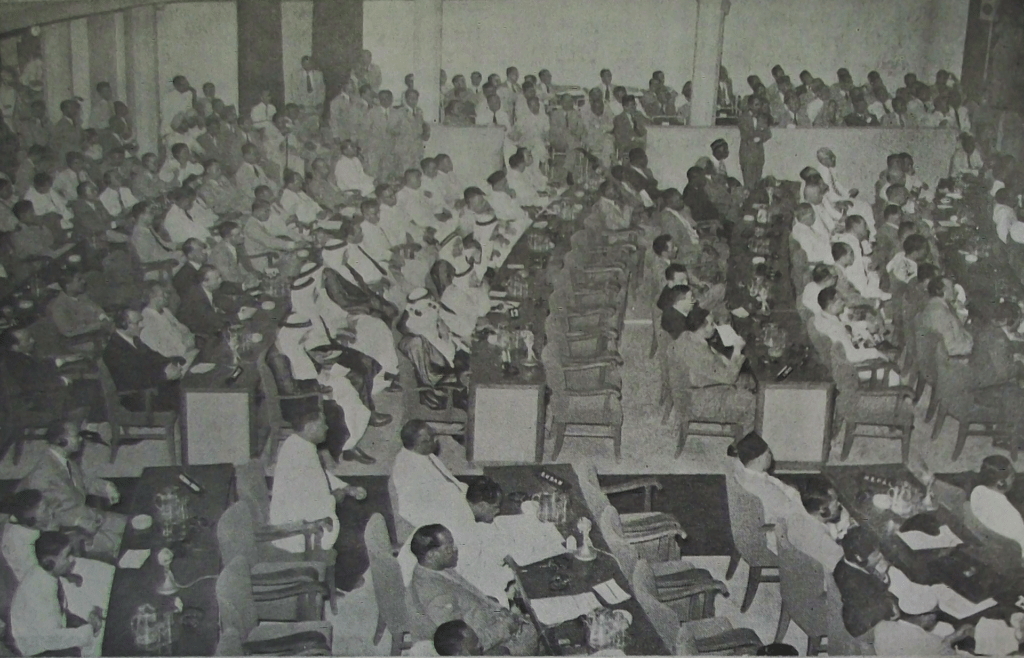

More than just its scenic appeal, Bandung was also a witness to one of the most defining moments in international relations during the post-colonial era: the KAA, also known as the Bandung Conference. Between 18 and 24 April 1955, 29 nations from the continents of Asia and Africa gathered at Gedung Merdeka (in English, the name means ‘Independence Building’), marking a critical moment for newly independent nations to stand tall on the world stage.

Back then when geopolitics was still largely dominated by the West—many of who still sought to reassert their influence on their former colonies[2]—KAA served as a declaration that the world’s political landscape could no longer be dictated solely by former colonial empires. The nations of Asia and Africa refused to be treated as the pawns in global political plays dictated by imperialist powers. They demanded political sovereignty and an equal voice in global governance, pushing back against a world order still dominated by Western powers. In Bandung, the voices that were once silenced finally echoed, bringing the message that independence was not only political sovereignty, but as much, the right to have a position on the world stage on more equal and fair terms.[3]

“…For many generations our peoples have been the voiceless ones in the world. We have been the unregarded, the peoples for whom decisions were made by others whose interests were paramount, the peoples who lived in poverty and humiliation. Then our nations demanded, nay fought for independence, and achieved independence, and with that independence came responsibility.” [4] – Sukarno

Seventy years have gone by since the conference. The world has evolved, along with Bandung. The city is now an innovative hub for creativity and entrepreneurship, serving as a center for education and innovation. Still, for many beyond Indonesia’s borders, Bandung is primarily known as the site of KAA, a significant event in the history of Global South diplomacy.

Let’s explore the allure and importance of Bandung: Why was it selected for KAA? What part did it play in Indonesia’s fight for independence? Does the solidarity that characterized KAA still resonate in its streets, or has it faded to a mere historical memory?

Bandung: Paris van Java or Something More?

When KAA was first planned, Indonesia naturally emerged as the leading candidate to host the event. Having recently gained independence, Indonesia positioned itself as a bridge between Asia and Africa, navigating the diverse agendas of post-colonial nations. Scholars like Herbert Feith have highlighted Indonesia’s active role in fostering diplomatic ties across the Global South, mainly through the leadership of Sukarno.[5] A charismatic and vocal leader, he relentlessly advocated solidarity among developing countries and anti-colonial struggles. On multiple occasions, he asserted that the struggle against colonialism was far from over and that newly independent nations needed to unite[6] and therefore, his vision of an anti-imperialist front made Indonesia an ideal host.

The next question was, where exactly should the conference be held in Indonesia?

Jakarta, as the capital, seemed to be the obvious choice, but in the end, Bandung was selected as the historic venue.[7] Bandung in 1955 was different from Jakarta, which was rapidly developing as the center of government. Although relatively close to Jakarta, Bandung was much calmer, smaller, and easier to manage from a security perspective. These considerations were necessary for a gathering of such scale—the venue needed to be where world leaders could engage in discussions without excessive political disruptions.

Bandung has also long been known as the “Paris van Java,” a moniker bestowed upon it during the colonial era due to its elegant Art Deco buildings, wide tree-lined boulevards, and temperate climate, which set it apart from the sweltering heat of Jakarta. Dutch colonizers saw Bandung as an ideal retreat[8], a place that could mirror the sophistication of Europe in the tropics. But beneath this romanticized image lies a question: Why did Bandung have to be Paris? Why couldn’t it simply be Bandung?

The nickname reflects a broader pattern of colonial urban planning, where cities in the colonies were often modeled after European counterparts to create a familiar sense of ‘civilization’ for the ruling elites.[9] But in doing so, it also imposed a hierarchy—suggesting that Western aesthetics were the standard to aspire to, rather than celebrating the indigenous character of the land.[10] Even as Bandung flourished into a hub of commerce and culture during that time, the “Paris van Java” label reinforced the idea that its value lay in its resemblance to a Western metropolis rather than its own indigenous, Sundanese identity.

This made it all the more important that Bandung was chosen as the site of KAA. The very city that once embodied colonial aspiration was now transformed into a site of resistance. Gedung Merdeka, the conference’s main venue, held its own irony: once known as Societeit Concordia[11], it had been an exclusive gathering place for Dutch expatriates—where Indonesian locals were not allowed to enter. By hosting the KAA, the same building that once symbolized European privilege became a witness to Global South history as formerly colonized nations came together, not to mimic their former rulers, but to assert their sovereignty and demand equality.

Societiet Concordia before its renovation in the 1920s. Exclusively for Dutch expatriates, the building famously had a rule ‘Verbodden voor Honden en Inlander’ (in English: Prohibitions for Dogs and Natives). Wikimedia Commons.

A City in Flames: the Fire That Defined Bandung

A key aspect of Bandung’s identity is its revolutionary past. Less than a decade before KAA, the city was engulfed in flames during one of the most dramatic episodes in Indonesia’s fight for independence: Bandung Lautan Api (The Bandung Sea of Fire).

The event occurred in March 1946[12], in the chaotic aftermath of World War II. Following Japan’s surrender in August 1945, Indonesia declared its independence, but the Dutch, backed by British forces, sought to reclaim their former colony. As part of their campaign, Dutch troops, assisted by British forces, moved into Bandung, demanding that Indonesian fighters retreat from the city. Under intense military pressure, the Indonesian leadership faced an impossible decision: surrender the city to the Dutch, or resist at all costs[13].

The response was extraordinary and unorthodox. Rather than allowing Bandung to fall back into colonial hands, Indonesian freedom fighters—alongside local civilians—made the fateful choice to burn down the southern part of the city before retreating to the mountains[14]. It was an act of revolutionary defiance: if they could not keep their city, then neither would their oppressors.

That night, the sky above Bandung turned red as flames consumed homes, businesses, and key infrastructure. Over 200,000 residents were forced to evacuate[15], leaving behind only scorched earth and the memory of resistance. The strategy was both tactical and symbolic—it denied the Dutch a functional city while proving that the people of Bandung would rather destroy their homeland than let foreign powers rule it.

Destroyed houses in the Southern part of Bandung after the Sea of Fire, April 1946. Wikimedia Commons.

Almost a decade later, when Bandung was chosen as the host for KAA, the decision carried profound significance. The city that once set itself ablaze in the name of freedom now became the meeting ground for newly independent nations.

Indonesia’s Strategic Ambition at KAA

Thus, Bandung was seemingly the ideal place to host the conference—its cool weather, controlled atmosphere, and its symbolic weight as a city of resistance made it a powerful setting for an anti-colonial movement and gathering of Global South leaders. But while the venue itself was fitting, a bigger question loomed: was Indonesia, as a newly independent nation, in a position to host an event of this scale? Only ten years after securing its independence, Indonesia was still struggling to rebuild from the devastation of colonial rule. Economic stability was a distant dream[16] and political challenges were mounting[17]. Hosting KAA was a bold, if not reckless move. So why did Sukarno insist on pushing forward?

Perhaps for Sukarno, KAA was never just about hosting a diplomatic event. It was an opportunity to place Indonesia at the forefront of the global anti-colonial movement. Perhaps Sukarno sought to prove that Indonesia was not merely a young nation searching for its place on the world stage, but a leader in the solidarity movement among newly independent countries and anti-colonial struggles.

Behind this grand vision, however, lay a strategic political agenda. One of Indonesia’s key objectives at the KAA was to garner support for its claim over West Irian (now West Papua)[18], which was still under Dutch control at the time. Although the KAA did not directly result in widespread international backing, it helped establish the moral and political narrative that Indonesia’s claim over West Papua was part of the larger anti-colonial struggle.

Yet, the question often overlooked was whether the Indigenous Papuans themselves had been consulted. The KAA championed the principle of self-determination, yet in Indonesia’s pursuit of West Papua, the voices of Papuans were largely absent from the discussion[19]. Like many other regions of the world undergoing post-colonial transition, West Papua was becoming a territory disputed by two countries and between two perspectives about what it means to be independent, to be truly free.

At present, the continuing human rights violations in West Papua remain one of the darkest legacies of Indonesia’s post-colonial history. The fight against colonialism was so loudly and proudly voiced in Bandung, but does the Indonesian government genuinely walk the talk? History shows that the right to self-determination enshrined in the conference was never truly upheld for the people of West Papua, who, until now, are still under military occupation[20] and restricted in their freedom of expression, association and self determination[21]. Indeed, the repression of activists working for the freedom of West Papua is still rampant[22].

Free West Papua Protest in Jakarta, December 2022. The main poster reads: “The UN has to take responsibility for the ongoing colonialism in West Papua.” Photo: Ambrosius Mulalt.

West Papua was not the only contradiction in Indonesia’s post-KAA trajectory. The Bandung that once hosted the conference as a symbol of anti-colonialism would undergo a transformation in the decades to come, one influenced by shifting national priorities and the rise of authoritarian rule.

By the late 20th century, Indonesia’s political landscape had changed dramatically. The nation that had once championed global solidarity increasingly prioritized economic growth and the so-called ‘stability’ over its founding ideals. This shift would influence Bandung’s evolution—not just as a city of history but as a place caught in the broader tensions between politics and progress.

But what happens when stability comes at the cost of political expression?

While the legacy of the KAA continues to be honored through plaques and ceremonies, the political forces shaping Bandung are no longer the same. The city that once set the stage for former colonies to reclaim their agency is now more widely known for its independent fashion brands, coffee culture, and creative start-ups. But while its creative industry flourishes, does it still nurture the radical energy that once made it a city of resistance?

This question, however, does not belong to Bandung alone—it is reflective of a larger national dilemma.

A City That Once Led, A City That Fell in Line: Bandung’s New Order Legacy

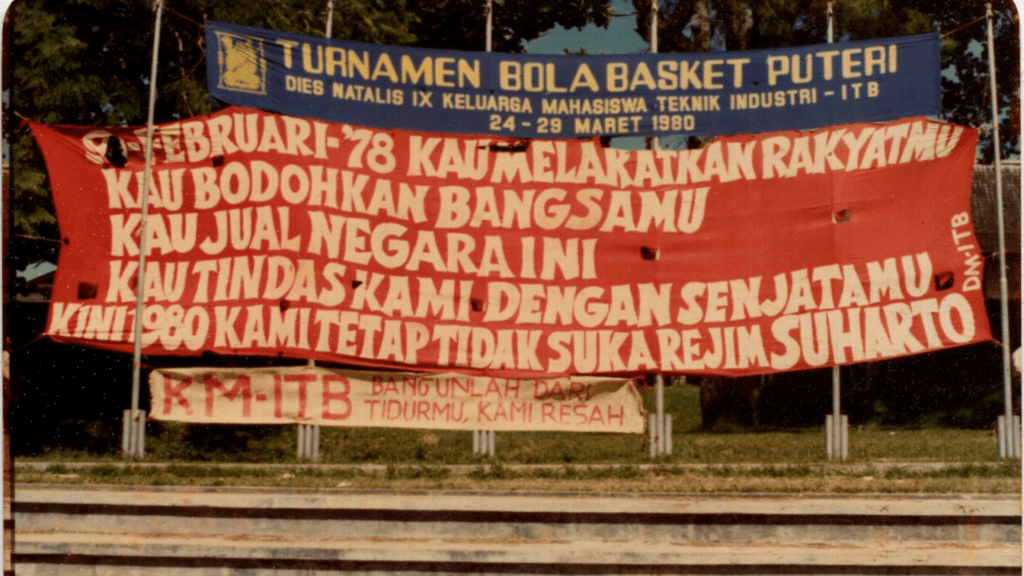

The transformation of Bandung was not coincidental; it was influenced by significant political changes in Indonesia, particularly during Suharto’s Orde Baru (New Order) regime (1966–1998). Once a center for radical student movements, Bandung experienced a notable decline in political activism during this period.[23] The universities, which had previously encouraged and thrived on anti-colonial discussions, became closely monitored by the government, leading to a systematic discouragement of political engagement among students.[24]

As Sukarno’s rule progressed, his concentration of power and economic mismanagement fueled growing unrest, culminating in protests and in the mid-1960s, students from Institut Teknologi Bandung (ITB) —where Sukarno studied engineering in the 1920s (then known as Technische Hogeschool te Bandoeng)[25]—together with Universitas Padjadjaran (Unpad), and Universitas Katolik Parahyangan (Unpar) actively protested against Sukarno’s administration.[26] These coordinated student actions across Bandung’s universities significantly contributed to the political pressure that led to the eventual transition to Suharto’s New Order regime.

The transition itself, however, was marked by violence and repression. The 1965 coup that ousted Sukarno and brought Suharto to power—later revealed to have been backed by foreign interests, including the United States[27]—left deep scars. For many students who had initially opposed Sukarno, the brutal anti-communist purge and authoritarian turn of the New Order quickly replaced any hope of reform with a climate of fear and disillusionment.[28] During the New Order, the tradition of political discourse and engagement threatened the regime, and students in Bandung participating in political protests often faced arrest, censorship, or expulsion.[29] The Suharto regime feared that Bandung, due to its vibrant intellectual environment, might become a center for dissent. Consequently, while Bandung remained a lively academic city, its political discussions became increasingly restricted.

Poster of ITB students’ resistance against the Suharto regime in 1980, two years after the Normalization of Campus Life/Student Coordination Board (NKK/BKK) policy was implemented. The text on the red poster: “You impoverished your people, you fooled your nation, you sold this country, you oppressed us with your weapons. Now it’s 1980, we still don’t like the Suharto regime”. Photo: Rahmat M. Samik-Ibrahim/VLSM.

So, during this time, Suharto prioritized economic development. While student activism was stifled, Bandung’s independent industries flourished, particularly fashion, design, and small businesses. This began Bandung’s emergence as a “creative city.” The city gained recognition for innovation, though not necessarily for political involvement. In many respects, this period laid the foundations of the ‘apolitical’ Bandung of recent years.

However, repression could not last indefinitely. As Indonesia moved into the late 1990s, economic instability and political discontent reignited student activism.[30] Bandung emerged as a central hub of resistance against Suharto’s regime. Students organized demonstrations, demanding an end to authoritarian rule and echoing the city’s rich history of resistance.

The 1998 Reformasi movement, which ultimately led to Suharto’s resignation, saw Bandung reclaim its political voice. While Jakarta witnessed the largest demonstrations, with student protesters occupying key government buildings, Bandung also emerged as an important site of student-led protests that contributed to Suharto’s resignation.[31] Universities throughout the city became rallying points for students who organized marches and demonstrations, calling for democratic reforms.[32]

The students in Bandung gathered in front of the Gedung Sate, the seat of the governor of West Java, during the nation-wide reformasi protest in May 1998. Photo: Djoko Subinarto/telusuri.id

Decades earlier, Bandung’s streets had burned in resistance against colonial rulers. This time, they echoed with the chants of students resisting authoritarian rule. The same city that had defied foreign domination was then standing against its government, proving that the fight for justice does not end with independence.

For a brief and crucial moment in the country’s history, Bandung seemed to, once again, be the city of radical energy.

Bandung Today: A City That Remembers, A Nation That Forgets?

However, as democracy settled in after 1998, the momentum of political activism in Bandung faded once again. Post-reformasi, the city, much like the country, shifted its focus toward economic development[33]. The independent creative industries thrived, the tourism sector expanded, and student movements became less prominent. While Bandung remained a center for intellectual discourse, the type of political mobilization that once defined it gradually diminished.

For a time, Bandung seemed to drift into political apathy. Between the early 2000s and mid-2010s, student activism in the city was seen as less radical than in Jakarta or Yogyakarta[34], leading to the perception that Bandung had become more interested in creative entrepreneurship than political resistance. As Bandung gained international recognition as a UNESCO Creative City in 2015[35], its identity became more associated with innovation and commerce rather than political activism.

Yet, in recent years, Bandung has begun to reclaim its reputation as a politically engaged city. In response to pressing national and global issues, student activism and public demonstrations have resurged, signaling that the spirit of resistance has not been lost but was merely dormant.

In January 2024, students at the ITB protested against the university’s policy encouraging tuition payments through online loan platforms[36]. Hundreds marched to the rectorate building, expressing concerns over the financial burden imposed by such schemes. The protests highlighted the students’ demand for more equitable and accessible education financing.

Most recently, the Indonesia Gelap (Dark Indonesia)[37] movement further exemplifies Bandung’s reawakened activism. In February 2025, hundreds of students gathered in front of the West Java Regional House of Representatives (DPRD Jabar) building in Bandung[38], protesting against budget cuts and policies perceived to undermine social support systems. Clad in black, symbolizing a nation in darkness, these demonstrations were part of a nationwide movement challenging the administration’s austerity measures.

Not only are there actions against the government, but Bandung is also the site for international solidarity actions. Thousands of protesters organized a rally in support of Palestine[39], and the same solidarity was shown when they raised more than USD 75,000 in donations for the Rohingya[40]. These actions show that Bandung’s legacy of resistance and South-South solidarity still lives on, carried on by a new generation that refuses to be silent in the face of injustice and oppression.

In June 2024, thousands of people gathered in front of Gedung Merdeka. They marched through the streets of Asia-Afrika to show solidarity with the Palestinian people and to call for #FreePalestine. Photo: jurnalposmedia.

The question, then, is whether this renewed activism in Bandung will continue to grow, or whether it will once again be dampened by economic pragmatism and political fatigue.

And, among all these actions demanding justice, the starkest reminder of the promises left from the Bandung of 1955 lies in the protests for West Papua. Gedung Merdeka, the same site where the KAA once championed self-determination for colonized nations, now witnesses demonstrations by Papuan students and activists demanding their own right to self-determination[41]. The irony is inescapable: a city that once symbolized freedom from colonial rule now stands as a backdrop to the struggle of Indigenous Papuans, who remain subject to militarization, human rights abuses, and suppression of their political voices and identities. The very ideals that Bandung once stood for—justice, independence, and equality—are now being demanded by those who are still denied them.

Seventy years later, as we walk these same streets, we must ask: Has independence truly liberated everyone, or have we simply learned to live with new forms of subjugation? Bandung still remembers. But remembrance alone is not enough. If Bandung and Indonesia are to truly honor the legacy of the KAA, then the question is not only whether we recall its ideals but whether we have the courage to fight for them once again.

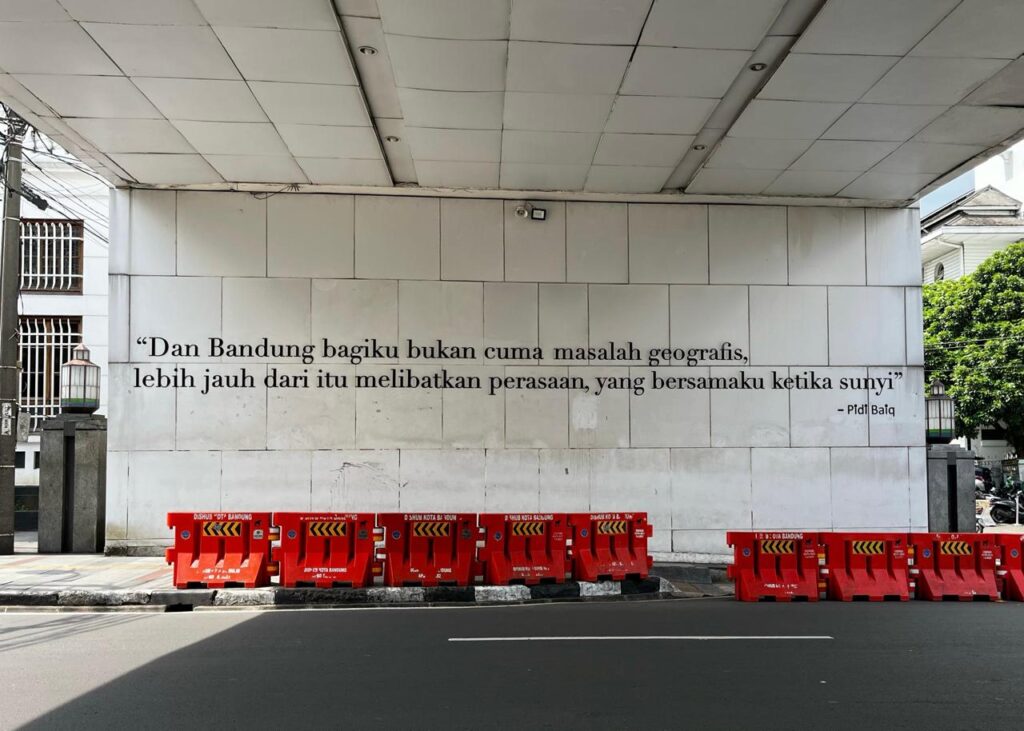

Another quote is on the opposite side of the pedestrian bridge wall on Asia-Afrika Street. The quote is by Pidi Baiq, a renowned artist from Bandung, and it roughly translates to: ‘And Bandung, for me, is not just a matter of geography; it goes far beyond that, carrying emotions that linger with me in solitude.’ Photo by: Farid A.

Endnotes:

[1] (2022, July 21). Mengenal Brouwer ‘Bumi Pasundan Lahir Ketika Tuhan Sedang Tersenyum’. Pikiran Rakyat. Retrieved March 6, 2025, from https://www.pikiran-rakyat.com/bandung-raya/pr-015065721/mengenal-brouwer-bumi-pasundan-lahir-ketika-tuhan-sedang-tersenyum

[2] Nkrumah, K. (1965). Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism 1965 (pp. 41-42). Thomas Nelson & Sons, Ltd., London.

[3] Timossi, A. J. (2015, May 15). Revisiting the 1955 Bandung Asian-African Conference and its legacy. The South Centre. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://www.southcentre.int/question/revisiting-the-1955-bandung-asian-african-conference-and-its-legacy

[4] Sukarno. [Address given by Sukarno (Bandung, 18 April 1955)]. In: Asia-Africa speak from Bandung. Jakarta: Indonesia. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 1955. pp. 19-29.

[5] Feith, H. (1962). The Decline of Constitutional Democracy in Indonesia by Herbert Feith. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York.

[6] Sukarno, Loc. Cit.

[7] Appadorai, A. (1955). THE BANDUNG CONFERENCE. India Quarterly, 11(3), 207–235. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45068035

[8] Vaswani, K. (2011, June 17). Bandung: The Paris of Java. BBC. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20110616-bandung-the-paris-of-java

[9] Nas, P. J. (2006). The Past in the Present: Architecture in Indonesia (pp. 47-48). Brill Academic Pub.

[10] Kusno, A. (2011). Behind the Postcolonial Architecture, Urban Space and Political Cultures in Indonesia (pp. 30-32). Taylor & Francis.

[11] (2008, January 20). GEDUNG MERDEKA (Tempat Berlangsungnya Konferensi Asia Afrika). Museum of The Asian African Conference. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from http://www.asianafrican-museum.org/gedungmerdeka.php?language=ind&page=gedungmerdeka

[12] Parinduri, A. (2024, August 16). Sejarah Bandung Lautan Api 1946: Kronologi Peristiwa & Tokoh. Tirto.id. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://tirto.id/sejarah-peristiwa-bandung-lautan-api-penyebab-kronologi-tokoh-gajf

[13] Smail, J. R. (1961). Bandung in The Early Revolution, 1945-1946 (pp. 148-150). Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

[14] Larasati, A. (2023, March 22). Bandung Lautan Api, 200 Ribu Warga Mengungsi ke Gunung. DetikJabar. https://www.detik.com/jabar/berita/d-6631013/bandung-lautan-api-200-ribu-warga-mengungsi-ke-gunung

[15] Smail, J.R., Loc. Cit.

[16] Nordholt, H. S. (2011). Indonesia in the 1950s: Nation, modernity, and the post-colonial state. Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde, 167(4), 386–404. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41329000

[17] Hindley, D. (1970). Alirans and the Fall of the Old Order. Indonesia, 9, 23–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/3350621

[18] McNamee, L. (2023). Settling for Less: Why States Colonize and Why They Stop (pp. 1-4). Princeton University Press.

[19] Kluge, E. (2020) West Papua and the International History of Decolonization, 1961-69, The International History Review, 42:6, 1155-1172, https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2019.1694052

[20] Minority Rights Group (2004, March 15). West Papuan’s desire autonomy and end to Indonesian military operations. Minorityrights.org. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://minorityrights.org/west-papuans-desire-autonomy-and-end-to-indonesian-military-operations

[21] (2016, September 21). Ensuring Freedom of Expression in West Papua [Joint Stakeholders’ Submission for the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) of the Republic of Indonesia UN Human Rights Council, 3rd Cycle (27th Session) April – May 2017]. TAPOL and Bersatu Untuk Kebenaran (BUK; United for Truth).

[22] Human Rights Watch (2022, August 15). Indonesia: Free Imprisoned Papua Activists. Hrw.org. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/08/15/indonesia-free-imprisoned-papua-activists

[23] Elson, R. E. (1999). Suharto: A Political Biography (pp.223-225). Cambridge University Press.

[24] Nugroho, H. ‘The Political Economy of Higher Education: The University as an Arena for the Struggle of Power’. in Hadiz, V. R. (2005). Social Science and Power in Indonesia (pp. 147-153). Equinox Publishing.

[25] Isnaeni, H. F. (2020, August 14). Sukarno Kuliah dengan Biaya Sendiri. Historia. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://historia.id/kultur/articles/sukarno-kuliah-dengan-biaya-sendiri-DWqnM

[26] Pamungkas, M. F. (2019, September 27). 9 Martir Gerakan Mahasiswa Indonesia. Historia. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://historia.id/politik/articles/9-martir-gerakan-mahasiswa-indonesia-vQJR9/page/2

[27] Vann, M. G. (2021, January 23). The True Story of Indonesia’s US-Backed Anti-Communist Bloodbath. Jacobin. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://jacobin.com/2021/01/indonesia-anti-communist-mass-murder-genocide

[28] (1998, August 1). Academic Freedom in Indonesia: Dismantling Soeharto-Era Barriers [Report]. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/1998/08/01/academic-freedom-indonesia/dismantling-soeharto-era-barriers

[29] Ibid.

[30] Tehusijarana, J.P. (2023). Indonesia’s Student and Non-student Protesters in May 1998: Break and Reunification. In: Budianta, M., Tiwon, S. (eds) Trajectories of Memory. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1995-6_13

[31] Wiratman, H. P. (2015). Press freedom, law and politics in Indonesia : A socio-legal study [Doctoral Thesis, Faculteit der Rechtsgeleerdheid, Leiden University].

[32] Subinarto, D. (2022, June 17). Menyambangi Gedung Sate Menjelang Momen Puncak Reformasi 1998. TelusuRI. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://telusuri.id/menyambangi-gedung-sate-menjelang-momen-puncak-reformasi-1998

[33] Firman, T. (2008). The continuity and change in mega-urbanization in Indonesia: A survey of Jakarta–Bandung Region (JBR) development. Habitat International, 33(4), 327-339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2008.08.005

[34] In the 2010s, Yogyakarta emerged as a prominent center for student activism in Indonesia, particularly with movements like #GejayanCalling in 2019, where thousands of students and civil society members protested against government policies perceived as undermining public interests. See: Mahpudin, Kelihu, A., & Sarmiasih, M. (2020). The Rise of Student Social Movement: Case Study of #GejayanCalling Movement in Yogyakarta. International Journal of Demos, 2(1), 21-42. https://doi.org/0.37950/ijd.v2i1.2

[35] UNESCO (n.d.). Creative Cities Network: Bandung. Unesco.org. https://www.unesco.org/en/creative-cities/bandung

[36] Bagaskara, B. (2024, January 29). Protes Bayar UKT Via Pinjol, Mahasiswa ITB Geruduk Gedung Rektorat. DetikJabar. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://www.detik.com/jabar/berita/d-7166173/protes-bayar-ukt-via-pinjol-mahasiswa-itb-geruduk-gedung-rektorat

[37] Satriawan, B., & Budiman, Y. C. (2025, February 20). Students lead ‘Dark Indonesia’ protests against budget cuts. Reuters. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/students-lead-dark-indonesia-protests-against-budget-cuts-2025-02-20/

[38] Firmansyah, M. A. (2025, February 21). Aksi Indonesia Gelap di Bandung: Pemerintah Telah Meninggalkan Kesehatan dan Pendidikan. Bandung Bergerak. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://bandungbergerak.id/article/detail/1598814/aksi-indonesia-gelap-di-bandung-pemerintah-telah-meninggalkan-kesehatan-dan-pendidikan

[39] Azzahra, F., & Muhammad, R. I. (2024, February 6). Ribuan Massa Bersatu dalam Aksi Al-Quds Kota Bandung. Jurnal Pos Media. Retrieved March 11, 2025, from https://jurnalposmedia.com/foto/ribuan-massa-bersatu-dalam-aksi-al-quds-kota-bandung

[40] Purwanto, H. (2017, September 8). Bandung raises Rp1 billion fund for Rohingyas. Antara News. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://en.antaranews.com/news/112580/bandung-raises-rp1-billion-fund-for-rohingyas

[41] Rajul, A. (2024, March 28). Aliansi Mahasiswa Papua Bandung Turun ke Jalan, Mengecam Tindakan Penyiksaan terhadap Masyarakat Sipil Papua oleh Prajurit TNI. Bandung Bergerak. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://bandungbergerak.id/article/detail/1597189/aliansi-mahasiswa-papua-bandung-turun-ke-jalan-mengecam-tindakan-penyiksaan-terhadap-masyarakat-sipil-papua-oleh-prajurit-tni