Read the rest of the series at focusweb.org/tag/kaa70.

by Shalmali Guttal

Presentation at the Public Discussion: Commemorating 70 years of the Asia-Africa Conference

29 April, 2025

Good afternoon everyone. I am Shalmali Guttal. I am a member of the Working Group (WG) on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP). I am joining you from India.

UNDROP was adopted by the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) and the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) in 2018. The WG for its implementation was established in April 2024.

For me, it is a double honour to be invited to speak at this commemoration event in Indonesia, whose leaders birthed and enabled the Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung in 1955, and UNDROP several decades later. There are some important parallels between the two that I would like to highlight.

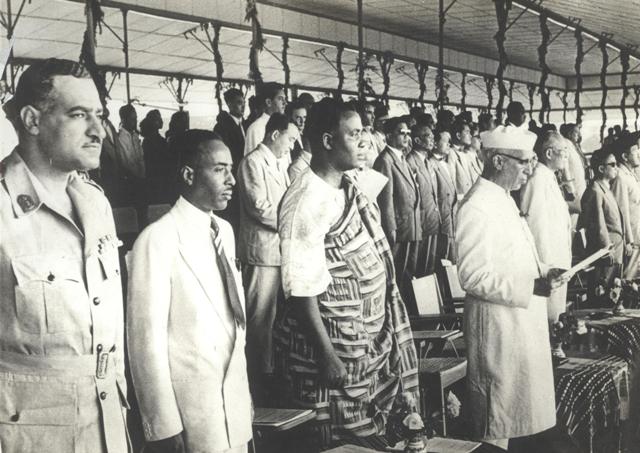

It was an Indonesian leader, Ali Sastroamidjojo, who proposed a conference of leaders from newly decolonized countries in Asia and Africa, which, after a planning meeting in Bogor in December 1954, resulted in the Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung from 18-24 April 1955. The Bandung conference led to the Non-Aligned Movement, the creation of the G77, and new sensibilities of South-South solidarity and cooperation across all the regions of the Global South.

And it was an Indonesian leader, Henry Saragih, from the Federation of Indonesian Peasants, who launched discussions in the early 1990-s with social movements and civil society organisations on the importance of articulating, realizing and defending the rights of peasants. These discussions intensified in La Via Campesina (LVC) in the following years and resulted in a charter on peasant rights drafted by SPI in 2002, and then a broader declaration on peasant rights collectively drafted by other LVC member organisations, which was presented by LVC in the UN Human Rights Council in August 2008.

From 2008 onwards, SPI and LVC built alliances with and won the support of numerous other social movements, CSOs, human rights experts and UN member states from the South. After a period of intense negotiations in the UN Human Rights Council from 2013-2018, UNDROP was adopted by the HRC and UNGA in 2018.

UNDROP is regarded as a “United Nations Declaration” after having been endorsed by the United Nations, but it remains first and foremost a “peasants’ bill of rights.” It was not States who launched the process, but peasants themselves, with the support of their representative organisations. And it was not States who shaped its content, but peasants, based on their knowledge and first-hand experience of the discrimination, oppression and social exclusion they have been subject to. This is evident in the inclusion in UNDROP of food sovereignty; agroecology; regulation of markets; rights of rural women; rights to seeds and biodiversity; rights to land, water and natural resources; protection of rural and migrant workers regardless of their status; right to participation; rights to justice; and numerous other civil, political, social, economic and cultural rights.

The UNDROP WG pays tribute to all social movements who have been involved in the negotiating process of the Declaration for their resolve and clear-sightedness. The Declaration would not have seen the light of day without their unwavering commitment to the equal and effective realisation of the human rights and fundamental freedoms of all individuals and groups who live and work in rural areas. In keeping with this spirit, the WG elected as our first Chair-Rapporteur, Ms. Genevieve Savigny, who is a peasant herself, and was closely involved in the negotiations that resulted in the adoption of UNDROP.

Just as the 29 independent nations represented at the Bandung Conference in 1955 constituted more than half the world’s population. UNDROP’s rights holders also constitute more than half the world’s population: they include peasants, fisherfolk, Indigenous Peoples, forest peoples, herders, nomadic rural peoples, rural and migrant workers in agricultural and food systems, rural women, and their families. Article 1 of UNDROP lays out the breadth and diversity of UNDROP’s rights holders. Rural women are highlighted as those facing persistent, intersectional discrimination and rights violations.

The ”Bandung Spirit” became—and remains to this day—a banner for the ideals of anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism, peace, sovereignty, self-determination, solidarity, and South -South cooperation to build robust domestic economies based on equality, justice and dignity of all peoples.

These ideals were not dreamed up by the state leaders who participated in the Bandung conference; they emerged from and were shaped by the struggles of the peoples in Asia and Africa, who were at the forefront of struggles for liberation from colonialism and resistance to imperialism, who gave their lives for liberty. These included peasants, Indigenous Peoples, fishers, workers and working classes, intelligentsia, women from numerous classes and backgrounds, local merchants, lawyers and many more.

The heroes of the Bandung Spirit were, very regrettably, not at the Bandung conference in 1955. Women were noticeably absent even among the leaders, although so many were at the forefront of freedom struggles back home. Even more regrettably, the decades after Bandung did not bring peace, liberation from settler colonialism and self determination to everyone. In many countries, the benefits of liberation and independence were enjoyed by particular classes, castes, races, ethnicities and religions, with women usually at the end of the line.

As former colonizing powers regrouped in the subsequent decades, the Bandung spirit was undermined by political demonization and persecution, criminalization of liberation ideologies, and the weaponization of debt, trade, and other economic and financial policies that recreated global structures of colonialism, imperialism and slavery.

The Bandung ideals of Asia -African cooperation on agriculture, rural development, technology sharing, and industrialization fell off the table. National development models were subverted by neoliberalism, and the expansion of corporate power in the economy, finance and governance. Countries of the South have grouped again through BRICS and regional formations, but competition has replaced cooperation and solidarity. The ten Bandung principles have been captured and reinterpreted on the basis of geopolitical and geoeconomic interests.

Reviving the spirit of Bandung in the present context demands urgent attention to long standing priorities: agrarian reform and rights of rural working classes to land, water and territories; food sovereignty and the right to food and nutrition; stable, secure employment and workers’ rights; social protection, and secure access to essential goods and services; economic and political systems that serve and respond to the needs of vulnerable peoples, and address the structural conditions of vulnerability to prevent vicious cycles of poverty and deprivation from recurring; protecting environments, eco systems and biodiversity; tackling debt and climate change through the principles of justice and historical responsibility; dismantling structures of historical discrimination among races, genders, ethnicities; and ending settler colonialism and extractivism that continue to dispossess people.

UNDROP and other international human rights instruments are important tools in rebuilding the spirit of Bandung in the present political, economic and environmental context. As multilateralism itself is faltering under the pressures of multistakeholderism, unilateral actions by a powerful few and cynical alliances among some countries, the international human rights architecture offers people all over the world a strategic tool to rebuild peoples’ multilateralism based on justice, equality, non-discrimination, peace, dignity and self-determination. UNDROP and other human rights instruments can serve as ethical benchmarks and criteria for assessing national, regional and international laws, policies, agreements, institutions and actions

In the present context, those at the forefront of struggles for liberation from the multiple, cascading and inter-meshed crises of our times–hunger, poverty, inequality, climate change, biodiversity loss, authoritarianism, military occupation and conflicts, gender based and other social-cultural violence and injustice, and extractivism–have been working classes, peasants and small-scale food providers, workers, Indigenous Peoples, women, students, journalists, lawyers, academics, parliamentarians and civil society organisations.

Despite facing persecution from authoritarian, fascist, patriarchal and oligarchic regimes, today’s heroes–like the heroes who fought for our liberation from colonial subjugation and rule–are not abandoning the terrains of struggle. UNDROP and other human rights instruments make these heroes visible, offer ways to protect their lives and efforts, and provide a basis for reviving the spirit of Bandung.

For us in the WG, UNDROP constitutes a new starting point, a paradigm shift towards a more inclusive society that recognises and values the essential contribution of peasants and people working in rural areas in the fight against poverty, hunger, exploitation and persecution in all their forms and dimensions; to the protection of the natural environment from pollution and degradation; to the nurturing and regeneration of biodiversity crucial for sustaining life; to the economic and social progress of our societies; and to the realisation of peaceful, just and inclusive societies where everyone’s rights are equally protected.

On behalf of the UNDROP WG, I urge governments, social movements, civil society, academics, parliamentarians and all those committed to equality, justice, peace, dignity, human rights and self-determination, to join us in implementing UNDROP.

Thank you.