Read the rest of the series at focusweb.org/tag/kaa70.

by Kheetanat Wannaboworn

“Should Thailand decide to accept the invitation to the conference,

the embassy should encourage Prince Naradhip, who could serve

as a skillful protagonist in the interest of the West to attend”

The State Department Telex to the US

Embassy in Bangkok

1 February 1955

Thailand was 1 of the 29 countries represented in the first Asian-African Conference in Bandung, Indonesia, in April 1955.[1] In the same year, Thailand became the signatory member of the Manila Pact – the Southeast Asia Collective Defense, whose establishing purpose was for the containment of communism in the region, specifically from China. Bangkok was where the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was located from 1955 until 1977.

In diplomatic history, the 1955 Bandung Conference was a starting point of contemporary Thai-Chinese foreign relations amidst hostilities created since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949.[2] Between 1948-1955, the expansion of communism was the focus of Thai foreign policy, particularly the perceived threats from PRC’s support to the communist movement in Thailand.[3] It was China’s new role in the Far East after World War II that required Thailand’s foreign relations to adjust, nevertheless.

In the bipolar world, how Thailand interacted on the world stage at the Bandung Conference was a sensitive question. The failure of Thailand’s World War II policy of cooperating with Japan was clearly the reason behind Thailand’s alignment with the US after the war. Under the ‘Shadow of the West,’ however, the seed of Sino-Thai’s diplomatic relations was planted. For this reason, the logic and reality of Thai foreign policy making at the ‘Age of Anxiety’ is important to understand non-alignment or neutralism as the backdrop of the Spirit of Bandung.

Thailand and Post-War International Orders

(Left) Thai citizens hold welcome banners for delegates attending the SEATO Ministerial Meeting at Ananta Samakhon Throne Hall. The meeting took place from 23-25 February 1955. Photo: thestatestimes.com. (Right) Prince Wan Waithayakorn or Prince Naradhip, known as Prince of Diplomacy, photographed at an international forum. Photo: Bangkok Post.

(Left) Thai citizens hold welcome banners for delegates attending the SEATO Ministerial Meeting at Ananta Samakhon Throne Hall. The meeting took place from 23-25 February 1955. Photo: thestatestimes.com. (Right) Prince Wan Waithayakorn or Prince Naradhip, known as Prince of Diplomacy, photographed at an international forum. Photo: Bangkok Post.

In September 1954, Thailand became one of the founding members of Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), with other signatories’ states including France, Great Britain, New Zealand, Australia, the Philippines, Pakistan, and the United States. SEATO was one of various efforts of the US-led postwar military institutions to contain communism globally, including the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 1949 (NATO) and the Australia-New Zealand-United States Treaty in 1951 (ANZUS), following the announcement of Truman Doctrine in 1947.[4] [5]

Between 1953-1954, the American-led initiative was not the only attempt to stabilize the world order after World War II. China’s reorienting its foreign policy towards neutralism and non-alignment in 1952 also proved successful in opening conversation with the rest of the Global South, starting with the Colombo Powers, who were the initiators of the first Asian-African Conference. The proposal on the Five Principles from Zhou En-lai’s meeting with Nehru in late 1953 was brought forward to the United Nations and influenced the Geneva Conference and its concluding agreements in July 1954 on the Indochina War, preventing Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, to take part in all forms of international military alliance.[6] [7]

It was this very achievement of Chinese diplomacy that shaped the US’s antagonistic perception of China and intensified its containment policy in Southeast Asia, the most concrete expression of which was the founding of SEATO. There were only two Southeast Asian countries that participated in the founding of SEATO: Thailand and the Philippines. Burma and Indonesia took neutral positions while Malaya denied formal support to the organization.[8] The Geneva Agreement on Indochina, as mentioned above, already warded off the newly independent French colonies from taking part in the alliance.

At the country level, Thailand had formulated its special position as the US’s closest ally in the region after World War II, following the collaboration between the Allies and the Free Thai Resistance Movement to repudiate the allegedly forced military alliance with Imperial Japan in December 1941. From 1938-1944, Thailand’s wartime leadership was provided by a fascist military dictator – Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram.

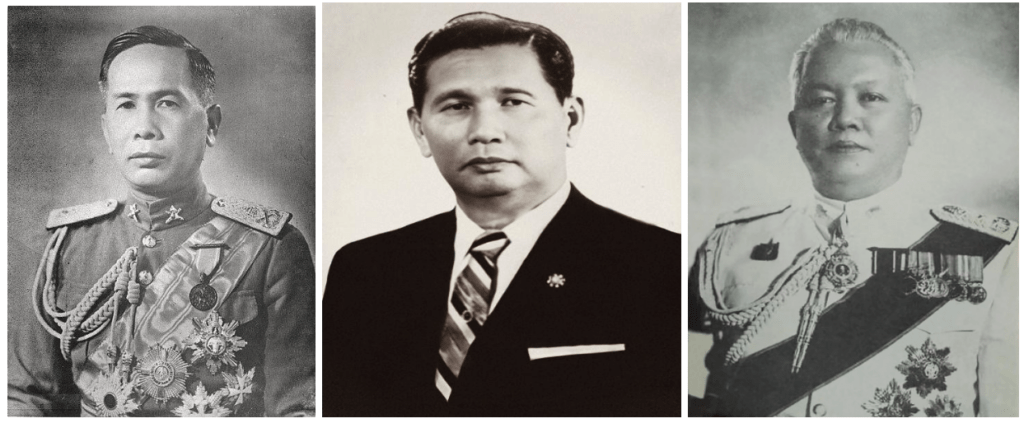

The “Triumvirate” of Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram, Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, and Police Chief Phao Siyanon in Thailand post-1947 coup d’etat. Photo: Wikipedia.

The “Triumvirate” of Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram, Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, and Police Chief Phao Siyanon in Thailand post-1947 coup d’etat. Photo: Wikipedia.

The immediate post-war period was marked by a succession of short-lived civilian governments from the Free Thai Movement. From 1947 – 1958, Field Marshal Phibun returned to his second premiership via a coup d’etat, but then claimed he was bringing about the characteristics of his era of democracy and publicly announced his siding with the anti-communist camp. It is argued that Phibun’s strategy stemmed from power politics within the Triumvirate – Field Marshal Phibun, alongside Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, and Police General Phao Siyanon – who were competing for political dominance amidst the US intensifying its intervention in Thailand’s security strategy and her economy.[9] [10] With Phibun losing to his rivals, the US divided its support between Sarit and Phao, the Royal Thai Army’s Commander-in-chief and the Royal Thai Police’s Director-General respectively. Both men fought to open their business, establish state-controlled enterprises, or provide safeguards for private companies’ benefits and business opportunities while operating in Thailand. In this power struggle, Sarit was supported by the US’s Ministry of Defense, the CIA was on the side of Phao Siyanon, with both trying to corner military and development aid flowing into the country.[11]

Tactical Diplomacy: Thai Foreign Policy Making in Uncertain Times

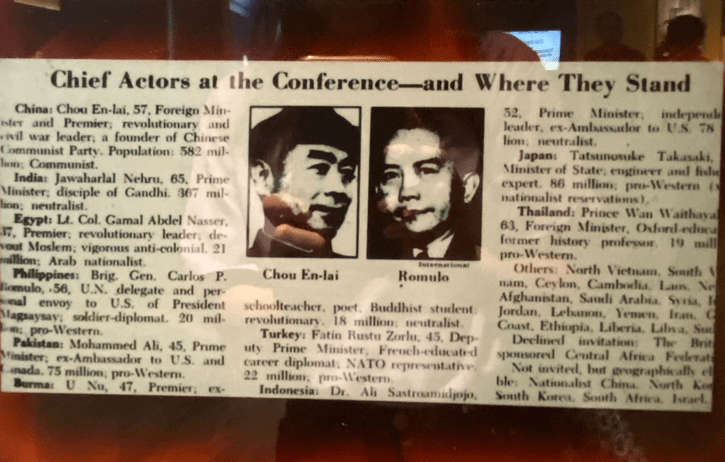

News Article ‘Chief Actors at the Conference – and Where They Stand’ showcased in Asia-Afrika Museum in Bandung. Photo: Kheetanat Wannaboworn (October 2024)

News Article ‘Chief Actors at the Conference – and Where They Stand’ showcased in Asia-Afrika Museum in Bandung. Photo: Kheetanat Wannaboworn (October 2024)

Though it was identified with the western camp, Thailand nevertheless sent a delegation to the Bandung Conference in April 1955 –a decision arrived at a consultation with the US embassy in Bangkok. From historical records, the invitation to Thailand was delivered when the Colombo Powers – India, Burma, and Pakistan, visited Bangkok after the Bogor Meeting in late 1954.[12] In February 1955, Thailand hosted the SEATO Ministerial Meeting in Bangkok, and the headquarters of the institution operated in this country’s capital thereafter until 1977.

At the Bandung Conference, Prince Wan Waithayakorn was the key personality to represent Thailand at one of the critical times for the country’s foreign policies. Being a top-tier and experienced career diplomat, one of the Prince’s missions at the Bandung Conference was crafted to explain the rationale of the country’s joining SEATO. The threat of communist expansion, as mentioned earlier, was the major concern for Premier Phibunsongkhram. Prince Wan Waithayakorn emphasized this in his speech on what he perceived as the PRC’s support of efforts to organize training of Thai-speaking Chinese and persons of Thai ethnicity in Yunnan for infiltration and subversion domestically.[13][14] It was also in this speech that Thailand stated its positive reception of Zhou Enlai’s Principles on Peaceful Coexistence and proposal for creation of Area of Peace. Prince Wan pointed out that Thailand joined SEATO to protect itself from external threats and ‘preserve peace.’[15]

“We intended to cooperate with all sides in building world peace”

Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram on the reason for Prince Wan Waithayakorn’s attendance at the Bandung Conference[16]

The PRC’s intentions towards Thailand was another objective of Phibun. Historians were uncertain whether the Premier had a plan in mind for the Thai representative to meet with Zhou Enlai.[17] Nonetheless, Prince Wan Waithayakorn and Zhou Enlai met at a dinner in Bandung.[18] The meeting not only opened up security matters in mind of the Thai side but also went beyond to discuss the establishment of Sino-Thai diplomatic relations, to which Zhou Enlai said, “the PRC can wait.”[19] The reconciliation with PRC was assessed to stem from the détente between the Communist and the Free World after the PRC’s shift in its foreign policies; prior to Bandung Thailand feared of being isolated, if the US and PRC were to pacify their competition.

For Thailand, the Bandung Conference became the stage to calibrate its diplomatic prowess. Prince Wan Waithayakorn who was first assigned as an observer, eventually became the rapporteur of the conference. He resorted to the debate oftentimes with reference to the Principle of the United Nations.[20] Reported back to the US, Prince Wan was suspicious for his diplomacy in Bandung but continued to be a trusted figure for the West throughout his career.[21]

The Age of Anxiety and Fear of a Small Nation: Thailand and the aftermath of Bandung Conference

Thailand was worried that the PRC’s shift towards neutralism from the exporting revolution, which found a positive reception in both Bandung and Geneva, would result in Thailand being excluded from the Bandung Club.[22]

For this reason, Thailand felt the immediate need to rebalance its relations with the Great Powers. For US-Thai relations, Premier Phibun embarked on an official visit to the US in June 1955. It was said that the visit left him with a strongly positive impression of the Free World. Upon his return, Phibun allowed registration of political parties, free speech, revoked control on newspapers, and promoted weekly press conferences from the Cabinet meeting.[23] As mentioned, the leaning towards liberal democracy was politically driven to build Phibun’s popularity from the ‘power politics’ within the Triumvirate. However, the emergence of freedom of the press in Thailand allowed criticism of the US’s military aid and a call for neutralism which was quite worrisome for the US.[24]

The Sino-Thai relations was another pillar in the rebalancing policy. The most significant move from Thailand during the Spirit of Bandung that lasted between 1955-1957 was from the Thai contacts with the PRC either in secret, openly, or from people’s diplomacy.[25] The last category, people’s diplomacy, consisted of exchanges of progressive MPs and journalists, trade unionists, cultural troupes, and athletic teams. These trips also included trade missions, including those designed to break the trade embargo imposed by the West. There were also trips sponsored by the Chinese People’s Institute of Foreign Affairs, with receptions from high-ranking officials, including Zhou Enlai and Mao Tse-Tung.[26] The Thai Government also arranged secret diplomatic delegations to China, some argued, which were said to be supported by Premier Phibun or Police General Phao Siyanon.[27]

“You must depend on yourself…You cannot find markets for your rice

and rubber in South Asia. We want trade with you. If we had diplomatic

relations and if you wanted any kind of industry, such as glass, paper or

textiles, we would help.”

Mao Tse-Tung’s interview to the MP Thep Chotinuchit’s delegation visit in the Autumn of 1955, on the General Principle of peaceful co-existence and Asian Solidarity against Imperialism[28]

This chapter on the relations between the PRC and Thailand closed when Field Marshal Sarit staged the second coup d’état in October 1958. More than 100 people, especially leftist politicians and newspaper crews, were detained. There were also orders to close down a number of Chinese schools and Chinese newspapers. These activities cited the security threat in Thailand from communist infiltration. On January 17, 1959, the import of all products from mainland China was banned.[29]

“China is always willing to develop equal and mutual beneficial

trade relations with Thailand on the basis of peaceful co-existence.

Sino-Thai trade was suggested by the Thai side, and it is now being

destroyed by the Thai Government; it therefore has no influence

whatever on China. On the contrary, this action of the Thai Government

of returning evil for good will only harm its own interest.”

The China Council for the Promotion of International Trade’s response to the Thai Government’s ban

In contrast, Thailand’s special relations with the US escalated very quickly after 1959 when anticommunism became the hegemonic discourse of Thai diplomacy. At the peak of the Cold War, Thai foreign policies were highly unbalanced and antagonized China and the USSR. As a close ally, Thailand was engaged in escalating conflicts in the region, including in Vietnam. It was not until the American retrenchment from the region after the Vietnam War that the process to normalize relationships with the Communist Powers restarted. In 1975, Thailand and China established diplomatic relations, leading up to the unusual alliance with China and the US to support Khmer Rouge-dominated Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea in the United Nations, as a counter strategy against Vietnam and the USSR’s growing interest in the region.[30]

From Bandung to BRICS

The state of Thai foreign policy at present is reminiscent of the age of anxiety. While not entirely similar, 21st century geopolitics and the US-China Trade War play key roles in creating tensions for this small, yet geographically strategic country in Asia Pacific, pushing her to define her position and alliance in the polarized world. If Thailand’s diplomacy and statecraft at the Bandung Conference could teach us anything, it should be to remind us of the Bandung Spirit: that free nations can collectively aspire to be independent in their statecraft and diplomacy from colonialism in all its forms and can collectively adhere to the concept of peaceful coexistence and collaboration, as opposed to the normalization of militarism that is heightening in our world today.

“All that I need is that for peace

You fight today, you fight today

So that the children of this world

Can live and grow and laugh and play.”

‘Hiroshima Child’ written by Nazim Hikmet in 1956. The quote was selected by Tricontinental’s ‘The Bandung Spirit Dossier’ as the essence of the Spirit of Bandung.[31]

Endnotes:

[1] Prince Naradhip, also widely known as Prince Wan Waithayakorn, was a career diplomat who served the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Thailand for five decades and had been entrusted by every government in those time to represent Thailand namely in the 1917 Peace Negotiation, the League of Nations (1928-1930), and later the United Nations. See Sripong, W. (2023). Prince Wan Waithayakorn’s Attempt for Rapprochement with the People’s Republic of China at the 1955 Asian-African Conference at Bandung. Manusya: Journal of Humanities, 26 (2023), 1-17. http://www.manusya.journals.chula.ac.th/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2623_Prince-Wan-Waithayakons-Atte_Sripong.pdf

[2] Chinvanno, A. (1990). Political Relaxation and Détente: Thai-Chinese Relations after Bandung Conference 1955-1957. Thai Journal of East Asian Studies, 3(1), 75-94. https://so02.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/easttu/article/view/51409/42575 (In Thai).

[3] Sripong, P.,Loc. Cit.

[4] Lee, Ji-Young. (2019). Contested American hegemony and regional order in postwar Asia: the case of Southeast Asia Treaty Organization. International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, 19(2), 237-267. https://research.ebsco.com/c/3q5j6g/viewer/pdf/bhzp6mrgyv

[5] On Truman Doctrine, See US Department of State’s Office of the Historians (n.d.). The Truman Doctrine, 1947. history.state.gov. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1945-1952/truman-doctrine

[6] Sripong, P.,Loc. Cit.

[7] US Department of State’s Office of the Historians (n.d.).Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), 1954. history.state.gov. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/seato

[8] Ibid.

[9] Chaloemtiarana, T. (2007). Thailand: The Politics of Despotic Paternalism. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York.

[10] Silpawattanatham Editorial Team. (2022, April 18). “Rachkru-Si Sao Thewet” Two Big Political Groups during the military dictatorship. Silpawatthanatham. Retrieved April 18, 2025, from https://www.silpa-mag.com/history/article_56576 (In Thai)

[11] Ibid.

[12] Chinvanno, A.,Loc. Cit.

[13] Chinvanno, A.,Loc. Cit.

[14] Sripong, P.,Loc. Cit.

[15] Chinvanno, A.,Loc. Cit.

[16] Fineman, D. (1997). A Special Relationship: the United States and Military Governmentin Thailand, 1947–1958. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, Hawaii.

[17] Sripong, P.,Loc. Cit.

[18] Pongpichit, C. (2015). Zhou Enlai Stateman who is a Military, Diplomatic, Economicsand Management prodigies. Matichon Printing House, Bangkok. (In Thai).

[19] Pongpichit, C., Loc. Cit.

[20] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Thailand. (2011). Meeting with Zhou Enlai in Bandung. The Commemoration of the 120 Birth Anniversary of H.R.H. Prince Wan Waithayakon Krommun Naradhipbongsprabandh. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Thailand, Bangkok. (In Thai).

[21] Sripong, P.,Loc. Cit.

[22] Wilson, David A. (1967). China, Thailand and the Spirit of Bandung (Part I). The China Quarterly (30), 149-169.

[23] Chinvanno, A.,Loc. Cit.

[24] Chinvanno, A.,Loc. Cit.

[25] Wilson, David A. (1967). China, Thailand and the Spirit of Bandung (Part II). The China Quarterly (31), 96-127.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Chinvanno, A.,Loc. Cit.

[28] Wilson, David A. (1967). China, Thailand and the Spirit of Bandung (Part II). The China Quarterly (31), 96-127.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Poonkham, J. (2022). A Genealogy of Bamboo Diplomacy: The Politics of Thai Détente with Russia and China. ANU Press, Canberra.

[31] Tricontinental (2025 April, 8). The Bandung Spirit. thetricontinental.org. https://thetricontinental.org/dossier-the-bandung-spirit/