Southeast Asia Political Dynasties Project II: Philippines

This is the second in a series of investigative projects exploring the structure and dynamics of governance systems in selected Southeast Asian countries. For other articles in this series, visit here.

As with most countries across the world, politics in the Philippines has historically been a family affair for the elites. Almost every politician that holds a position of power is somehow related to, by blood or patronage, to a political dynasty. It is nearly impossible for one to dive in, navigate, and survive the treacherous and oftentimes deadly political terrain absent the support of a powerful surname.

Despite policy safeguards that aim to regulate the concentration of power—such as the term limits set in the 1987 Constitution—elite families have devised ways to persist in or elevate their positions, especially during election season. Public welfare programs have been instrumentalized by elites as patronage to expand their influence or sustain popular support. In effect, governance has been reduced to mere schemes for maintaining a stranglehold over constituents, thereby perennially undermining the peoples’ rights to public services.

Elite families also thrive in politics from alliance building and power-sharing agreements with other elites who also stand to gain in either preserving or changing the status quo. Over the last 50 years, the country has seen the rise, fall, and comeback of various dynasties. Most notable is the return of the Marcoses to the highest seat of power in 2022, 36 years after the Marcos dictatorship was overthrown by the 1986 EDSA Revolution. Times change, but the rules of the game as well as the players remain. As a popular Filipino saying goes, “weather-weather lang iyan,” a metaphor likening the cycle of political families in government posts to weather conditions: changing, but ever-constant.

A little over a year after the 2022 national elections, the alliance of President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. and Vice President Sara Duterte show glaring cracks as political clans behind them scramble for power. With the upcoming 2023 barangay (village) elections, political families big and small are now moving towards firming up electoral machineries to prepare for the next big thing: the 2025 midterm elections, the 2028 national elections, and possibly a referendum for charter change.

As part of Focus on the Global South’s Dynastic Politics in Asia Dossier, this paper will look into some key developments in the first year of the Marcos-Duterte alliance indicating a rift between them and those pointing to the continuation of the tactical unity. Considering these developments, the paper seeks to answer two questions: (1) whether it is still in the interest of these dynasties to maintain the alliance and (2) what the persistence of this alliance or its dissolution would mean for the future of the Philippine political landscape.

The ties that bind Marcos and Duterte

Prior to the creation of the Marcos-Duterte alliance during the 2022 elections, the two dynasties have been exchanging political favors. At the onset of the partnership, each clan was able to provide support that the other needed to realize their political ambitions.

On the one hand, in 2015, when Rodrigo Duterte or “Digong” was running for president, his support base came largely from the central and southern islands of Visayas and Mindanao. He needed a power broker from the North, and that was what the Marcoses provided.

Hailing from the northern province of Ilocos Norte, the Marcos dynasty first ruled the Philippines from 1965 until they were ousted by a People Power Revolution in 1986. Throughout Ferdinand Marcos Sr.’s 21-year rule—first as president, then as dictator—it is widely believed that he and his cronies orchestrated the detainment, torture, disappearance, and killing of hundreds of thousands of people that were critical or suspected of being critical of the Marcos regime. His administration was also hounded by plunder and corruption cases from their ill-gotten wealth amassed during the Martial Law years.

After being overthrown and exiled in 1986, the Marcoses were allowed to return to the country five years later by then President Corazon Aquino to face criminal charges. This however set the stage for them to regain provincial bailiwicks in the northern province of Ilocos Norte. Thereafter, the Marcoses made various attempts to re-enter the national political scene. However, they were mostly thwarted by their family’s association with thievery, corruption, nepotism, cronyism, as well as the people’s disgust with the dictatorship and the thousands of human rights abuses under their regime.

For the most part of their hiatus, the Marcoses kept to themselves in Ilocos Norte, but held tightly onto gubernatorial and congressional posts. Banking on the loyalty of their hometown constituents, the Marcoses then worked towards re-consolidating the “Solid North” voting bloc comprising three vote-rich regions. They also strived to court the Waray (Eastern Visayas) bloc through another prominent political clan: the Romualdez, family of former first lady Imelda Marcos.

In 2010, the national elections that seated Benigno Aquino III and brought back the Liberal Party into power also saw the comeback of the Marcoses, when Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. clinched a senatorial seat, while his mother Imelda and his sister Imee Marcos also won congressional and gubernatorial seats, respectively.

In the same year that Duterte decided to run for president, Imelda Marcos announced his son’s bid for the vice presidency. Although Duterte and Marcos Jr. did not officially become running mates, many still latched on to the tandem. Based on the results of an exit poll conducted by TV5 and Social Weather Stations, political analyst Miguel Reyes said that the unofficial pairing was beneficial to both Marcos and Duterte. Citing a report by Mahar Mangahas, Reyes said that of Duterte’s 40 percentage points of the vote, “only 13 came from voters of his co-candidate Alan Peter Cayetano; the bulk of 18 came from Marcos voters.” As such, “[if] the exit poll was representative of the actual vote, then of the 16.6 million or so votes obtained by Duterte, about 45 percent, or nearly 7.5 million, came from those who also voted for Marcos.”[i]

At the same time, both the Marcoses and the Dutertes largely benefited from the growing public disillusionment with the Aquino administration. Representing the Liberals or the “yellow” movement, the Aquino regime at the time was in hot water for mismanaging various crises that earned public ire. These include various corruption scandals involving elites while the entire nation suffered in poverty and destructive climate disasters, the drastic mismanagement of a police operation that saw one of the highest fatalities in government forces, and the implementation of economic policies that only benefited the rich. Consequently, the Aquino administration became widely perceived as “elitist,” detached from the realities and struggles of ordinary Filipinos. This was further reinforced by the Aquinos’ oligarchic ties. All these have put into question the legacy of the 1986 EDSA revolution, which brought the Aquinos and the Liberals into power while promising inclusive democracy and better living conditions for Filipinos.

While the Aquino family is celebrated for their role in fighting the Marcos dictatorship and helping restore democracy in the 80’s, their political influence and legacy have also been a subject of debate and criticism due to their oligarchic ties. Their prominence in national politics can be traced back to Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Sr., who was a renowned journalist, political opposition leader, and a staunch critic of former dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. Ninoy Aquino’s assassination in 1983 triggered widespread outrage and eventually played a pivotal role towards the realization of EDSA People Power Revolution in 1986 against the Marcoses. Ninoy’s widow, Corazon “Cory” Conjuanco-Aquino became the first President under the 5th Republic, which signaled the beginning of the post-EDSA reign of liberal democracy.

But while Ninoy Aquino was criticizing the Marcos regime, his wife’s cousin Danding Cojuangco was amassing massive lands and wealth as one of Marcos’ most powerful “cronies.” Danding was also involved in the Coco Levy Fund scam, where Marcos and his cronies conspired to impose additional taxes on coconut farmers, under the pretense of developing the coconut industry and giving farmers a share of the investments. However, the funds collected were used by Marcos, Cojuangco, and others for personal profit.

The Cojuancos weathered the regime change brought by the EDSA Revolution and saw further expansion of business interests during the Aquino administration. Despite influencing landmark policy reform that challenged oligarchic power, Corazon Aquino drew flak as heir to Conjuanco-owned Hacienda Luisita, one of the largest sugar estates in northern Philippines. A little over a year in her presidency, the Mendiola Massacre happened, where military and police forces gunned down several peasant leaders protesting the government’s inaction towards agrarian reform.

Less than two decades after Cory’s regime, the country would vote for another Aquino into power. The resurgence of nostalgic democratic fervor following Corazon Aquino’s passing in 2009, and the public’s discontent with the corruption scandals under the preceding Arroyo and Estrada administrations cemented a presidential win for Benigno “PNoy” Aquino III in the 2010 elections.

Pnoy’s term, however, was hounded by various inefficiencies and controversies. These include the alleged corruption in rehabilitation efforts after the devastation of Typhoon Haiyan, which led to more than 6,000 deaths, more than 1,000 disappearances, and more than USD 2 billion-worth of damages. Another notorious corruption scandal was that involving the Disbursement Acceleration Program (DAP), where cabinet members reallocated public funds without congressional approval to certain “big ticket” projects. Another critical issue was the PNoy government’s mishandling of “Oplan Exodus,” the police operation in Mamasapano Municipality against the Jemaah Islamiyah and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front that resulted in the death of 44 government forces. At the same time, the PNoy administration’s hyperfixation on economic growth and its persistent adherence to the tenets of neoliberalism have exacerbated inequality and poverty. Growth rates were not directly felt by the people as jobs remained insecure, wages were paltry, social services were inaccessible, and land reform was undermined.

Altogether, the Aquinos’ historic ties with oligarchs, the corruption scandals that hounded PNoy’s administration, and their failure to uplift the lives of ordinary Filipinos gave rise to anti-liberal sentiments. The Aquinos—and by extension the Liberals—were perceived as having failed to fulfill the promise of inclusive democracy and equality that emanated from the 1986 EDSA Revolution. These sentiments were further fueled by the Marcoses and the Dutertes to bolster their campaigns towards the 2016 elections.

Duterte aids Marcos revisionism

Despite the crisis of legitimacy that hounded the Liberals, Marcos still lost the vice presidency to Liberal Party standard bearer Leni Robredo, albeit by a very small margin. On the other hand, Rodrigo Duterte—who strongly projected an anti-liberal and anti-establishment rhetoric that resonated well with public sentiment against oligarchic rule—won a landslide victory for the presidency.

Rodrigo Duterte’s political career ironically started in 1986 when he was appointed as the OIC vice mayor of Davao City at the height of the 1986 EDSA Revolution, by the incoming revolutionary government of Corazon Aquino. He eventually served consecutive Mayoral terms from 1988 to 1995 under PDP-Laban, from 2001 to 2007 under the Nacionalista Party, and from 2013-2016 under the Liberal Party. In 2015, when Duterte was prodded to run for president, he was courted incessantly by PDP-Laban to become their standard bearer, something that he repeatedly declined due to “lack of enthusiasm”. After some dramatics, Duterte agreed, and became the underdog candidate that challenged the “imperial Manila” brand of governance, representing various Visayan and Mindanaoan political blocs.

Duterte, however, is by no means a conventional mayor. He was known for extra judicial killings and employing death squads to combat illegal drugs in Davao. During his presidential campaign, Duterte vowed to elevate his violent approach to the drug problem at the national level. He also capitalized on the growing public discontent against the Aquino Administration and the Liberal Party, as well as the anti-EDSA narratives being propagated by Marcos supporters at the time (as Bongbong Marcos was also vying for the vice presidency). Come May 2016, Duterte won by a landslide of 16 million votes, cementing this claim to the presidential seat.

Tapping into people’s frustrations with elite politics and liberal democracy, Duterte ushered the wave of propaganda narratives that demonized the opposing “yellow” (liberal) forces. The liberals were criticized for being hypocritical, as they failed to establish participatory governance and better living conditions despite giving primacy to democracy and human rights. Duterte also undermined the concept of human rights, portraying it as being contradictory to peace, order, and development. Development, in Duterte’s playbook, will not be realized by respecting human rights but by enforcing social order with an iron fist. This narrative resonated with a lot of Filipinos, whose everyday lives have been entangled with chaos and violence (crimes, wars, resource conflicts) and for whom the concept of human rights has been rendered meaningless, whether in times of liberal democracy or dictatorship. For these people, a strongman leadership was necessary to correct what they perceived as the inherent “lack of discipline” and “unruliness” among Filipinos.

This narrative also paved the way for Duterte’s bloody “war on drugs” and the state policy of “red-tagging” and “terror-tagging”, which involved the often unfounded and malicious labeling of human rights defenders as government destabilizers. Institutions necessary for a well-functioning democracy—such as the Commission on Human Rights, the separation of state powers, the media, and civil society—were also repressed or captured.

President Rodrigo Duterte (L) sworn in as President in 2016, with Sebastian Duterte (M), then Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte and Vice Mayor Paolo Duterte. Photo from Reuters for Philippine Daily Inquirer. From article: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1511425/political-dynasties-not-bad-and-is-here-to-stay-duterte

The demonization of human rights and democracy provoked by Duterte provided fertile ground for the whitewashing of the Marcos-led Martial Law era. Activists who fought for democracy and bore witness to or experienced atrocities during the Marcos dictatorship were discredited and labeled as “rebels.” The unspeakable brutalities they faced were justified on the grounds that they were destabilizing peace and order under the Marcos regime. This allowed the Marcoses to conjure up a “Golden Age” image for the Martial Law years, disseminating it through the same social media channels that propped up pro-Duterte propaganda. Over the last three decades, the Marcoses have been wanting to reinvent their family’s history and reclaim political power after the shame brought about by the ouster of the Marcos patriarch in 1986.

Pushing the envelope even further, Duterte intervened to have the former dictator, Ferdinand Marcos Sr, buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani (Heroes Cemetery) within the first 100 days of his presidency. The Marcoses have long yearned for this since their return from exile, as it gave them ground to revise history in their favor. For Duterte, this was a fitting recompense for the electoral support mobilized by the Marcoses through the “Solid North” vote bloc.

As such, despite Marcos Jr. losing the vice presidential race in 2016, the Marcoses still benefited greatly in their alliance with the Dutertes. In 2019, Imee Marcos won a senatorial seat largely owing to the revisionist propaganda that Duterte paved way to.

Building the “Uniteam” of dynasties

Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and Sara Duterte during massive campaign sorties in 2022. Photo by Al Vicoy for Manila Bulletin: https://mb.com.ph/2022/4/30/uniteam-eyes-triple-miting-de-avance-ahead-of-may-9-polls

When the end of his term approached, Duterte knew that he needed to maintain his foothold in national politics. Though enjoying high trust ratings for most of his term, a landslide victory against the opposition was needed to cement the legitimacy of his governance. Duterte also needed protection from the International Criminal Court (ICC), which authorized an investigation on reported crimes against humanity committed under his administration’s “war on drugs.”

As talks of the 2022 elections first came to the fore, many were expecting Rodrigo Duterte’s daughter, Sara, to run for president. Sara topped the presidential preference polls, and her father had the resources to support her campaign. But mimicking Digong’s tactics in 2015, Sara also defied people’s expectations by not filing her candidacy for President and instead pursuing a reelection bid as mayor of Davao City.

But everyone knew that Sara was just playing the “substitution game” like her father did in 2015 to dramatize his candidacy. People expected that Sara would withdraw her candidacy for Davao mayor and substitute another political party’s “placeholder” presidential candidate.[ii] But perhaps Duterte’s camp miscalculated the Marcoses’ eagerness to retake the presidency. They must have thought that the Marcoses would be willing to give way to Sara’s ambitions given her popularity in the polls. But on October 6, 2021, Marcos Jr. filed his presidential candidacy.

Despite this, Rodrigo Duterte had then still urged Sara to pursue the presidency as standard bearer of his party, Partido Demokratiko Pilipino (PDP-Laban). But to his dismay, Sara announced her decision to run for vice president on a joint ticket with Marcos Jr. and as the candidate of Lakas–Christian Muslim Democrats (Lakas-CMD), the party of the infamous former president and now Congresswoman Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. In November 2021, the “Uniteam” coalition was formalized, bringing together the most prominent and notorious dynasties in Philippine politics, who threw their support behind the Marcos-Duterte ticket. One of the most influential clans that pledged support for the Uniteam was the Estradas, despite their bitter history with Arroyo. The Estradas brought with them the Pwersa ng Masang Pilipino (PMP) or Force of the Filipino Masses, the political party headed by former President Joseph Ejercito Estrada.

The Estradas and the masa (masses) vote

The Pwersa ng Masang Pilipino (Force of the Filipino Masses), is a prominent political party in the Philippines founded by actor-turned-politician and former President Joseph Ejercito “Erap” Estrada who, by winning the 1998 National Elections, also cemented his enduring influence in the country’s political landscape. Through the PMP, Estrada has seated his wife and progeny in various local and national positions, including the Senate, during the last two decades.

Erap, who won popular support, saw a sharp decline in trust ratings as his administration quickly became mired in various corruption scandals, particularly in the form of illegal gambling payoffs and kickbacks. The growing public discontent culminated in the Second EDSA People Power Revolution in January 2001, where mass protests demanded Estrada’s impeachment/resignation. In this event, the military and state police withdrew its support for the administration, and along with the Supreme Court, declared the presidential seat vacant. Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, then Vice President, was sworn in, effectively ousting Estrada from power. Arroyo then ushered a series of investigations on Estrada’s alleged corruption scandals, placing him under house arrest.

In the 2004 national elections, capitalizing on the steadily declining public trust on the Arroyo administration, the Estrada family and the PMP played a vital role in consolidating the political opposition. Gloria Arroyo eventually won the said elections, but the Estrada-influenced opposition continued with a barrage of corruption scandals, exposés, and destabilization attempts against Arroyo.

In the 2010 elections, Estrada was allowed to run for the presidency as the standard bearer of PMP. He was bested by Benigno Aquino III and the Liberal Party, but only by a small margin, attesting to the party’s strength. In the 2016 National Elections, Estrada and the PMP endorsed Duterte’s candidacy and helped consolidate a broader base of supporters particularly in Metro Manila, which is considered the PMP’s core bailiwick. He also endorsed Bongbong Marcos’ Vice Presidential bid.

In 2019, the Estradas and the PMP suffered a total defeat, with Erap losing his mayoral bid for the city of Manila, and his sons Jinggoy and JV losing their senatorial bids by a small margin, causing a rift between the siblings. In the 2022 National Elections however, Jinggoy and JV, though running under different political parties, won senatorial seats through their connections to, and support of the Uniteam.

Jinggoy Estrada (L), and JV Ejercito (R), both sons of former President Joseph Ejercito-Estrada (M) simultaneously became members of the Philippine Senate in 2013 and 2022. Photo from the South China Morning Post: https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3150775/duterte-marcos-estrada-cayetano-pacquiao-cant-beat-philippines

First crack in the alliance

Rodrigo Duterte was not ecstatic over the creation of the Marcos-Duterte tandem. It bewildered him that Sara settled for the vice presidency when she was the most popular presidential choice. Expressing his frustration, Digong made derisive attacks against Marcos Jr., publicly calling him a “weak leader with baggage.”[iii] The former chief executive even fueled controversies regarding Marcos’ alleged cocaine use. These remarks signified the first crack in what Imee Marcos referred to as the “Marriage in Heaven.”[iv]

Despite Digong’s tirades, the Marcos-Duterte tandem garnered an unprecedented 31.6 million and 32.2. million votes respectively, marking the highest number of votes ever recorded for the Presidential and Vice Presidential seats and claiming a landslide victory against their rivals. More than just preempting any potential challenges to the tandem’s legitimacy that might be mounted in the form of electoral protestsーsomething Bongbong Marcos is familiar with after incessantly protesting former Vice President Leni Robredo’s electoral win in 2016 and alleging fraudーthe landslide win was a statement by the UniTeam against political detractors and the opposition and a testament to the people’s mandate for their leadership and the tremendous power they wield.

Behind the accolades, however, some things cannot simply be overlooked. One is the absence of the Duterte patriarch’s blessing, something that the Marcos camp needed to clutch at at the time. Duterte Sr., despite issuing statements to support the incoming president, treated Marcos blandly during the turnover ceremonies at Malacanang Palace. Second was the fact that Sara Duterte had more votes than Bongbong Marcos, which attested to the magnitude of Duterte’s influence and the power of their electoral machinery. Overtime, this stirred up hushed narratives that the Marcoses owed the Presidency to the Dutertes.

Lines drawn and crossed

The waning of the election season traditionally marks the commencement of another equally significant political event: the appointment of key government officials, particularly into cabinet and bureaucratic posts.

Among Marcos’ campaign promises (especially to the Dutertes) was the continuation of the previous administration’s programs. This however did not mean the continuation of Duterte’s political appointees in various government agencies, though some of these officials had hoped that they would be retained in their positions. Within the first few months of his presidency, Marcos called for the “rightsizing” of bureaucracies. Subsequently, a number of government posts have been vacated, floated, and entire divisions and programs de-budgeted. Marcos’ first act as president was to decommission the Presidential Communications and Operations Office and the Presidential Anti-Corruption Commission, which were populated mostly by Duterte’s political stalwarts. Duterte appointees in the Commission on Audit, Civil Service Commission, and the Commission on Elections were bypassed in the senate commission on appointments hearing, allowing Marcos to fill in these positions with his appointees. A few months down the line, Marcos’ newly appointed interior and local government chief Ben Hur Abalos compelled numerous generals and high ranking officials under the Philippine National Police to submit their courtesy resignations.

Apart from these however, the most crucial appointments are cabinet positions which are often offered as a means for political patronage or to square debts with political allies during the elections. For her part, Vice President Sara Duterte eyed the Department of Defense post as early as the electoral campaign period, which Marcos nodded to, in line with her (and the previous administration’s) anti-terrorism and counter-insurgency agenda and push for mandatory military service. But when Marcos consolidated his cabinet, Sara Duterte was instead positioned as Department of Education Secretary.

Shortchanged or golden goose?

Many political observers say that Sara’s appointment as Education Secretary was a deliberate ploy to undermine her influence. The defense secretary position which she had been vying for would have given her a direct line with the military. The defense portfolio would have been more strategic for the Dutertes, given how Sara’s father had already nurtured positive relationships with the military during his presidential term. Duterte had significantly increased salaries of soldiers and policemen and appointed a number of ex-military men to his cabinet. Marcos knew this and probably did not want to give Sara the privilege of coddling one of the most powerful state instruments that his family had relatively less influence in.

Meanwhile, the position of education secretary can perhaps be considered the polar opposite of the defense secretary, as far as the Dutertes’ agendas are concerned. For one, compared to the military, the Dutertes have relatively weaker footing in the education sector. During his term, Rodrigo Duterte’s special treatment of the military was often contrasted by critics with the deplorable working conditions that teachers had to endure, including low wages, paltry allowances and benefits, and a grueling workload. As such, Sara needs to work her way up from a negative standing in order to build relations with her primary constituency as education secretary. Second, during Duterte’s presidential term, a huge corruption issue in the Department of Education (DepEd) was exposed. Sara is therefore handed the difficult task of cleaning up after the mess and regaining public trust.

In this light, Sara might have been shortchanged. But on the other hand, the DepEd historically has the highest budget share among all other agencies, which had an astounding 11% increase from PhP 801 billion in 2022 to PhP 895 billion in 2023 (USD 1.6 billion increase), while the Department of Defense saw a 7% decrease this year, to PhP201 billion (USD 3.5 billion)[v].

From cracks to coups

Among the developments indicating cracks in the Marcos-Duterte pact, perhaps one of the most revelatory was the demotion of Congresswoman Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo—one of the Dutertes’ closest political allies—from senior deputy speaker to deputy speaker last May 2023.[vi] Although the title of senior deputy speaker is simply ceremonial, many observers nonetheless regarded Arroyo’s demotion as the House leadership’s way of placing her in the sidelines.

There were speculations (reinforced by subsequent developments) that what triggered the demotion was Arroyo’s alleged involvement in a coup plot against House Speaker Martin Romualdez, cousin of President Marcos Jr.

In an attempt to brush off the allegations, Arroyo issued a statement downplaying her demotion as being “part and parcel of Philippine politics.”[vii] Addressing suspicions that she was still gunning for the speakership, Arroyo admitted that while she initially eyed the position after Marcos Jr. was elected president, that was no longer the case. Her change of heart came after supposedly realizing that the President was “most comfortable” with having his cousin Romualdez lead the House.

In contrast, Sara Duterte made it obvious that she did not take Arroyo’s demotion lightly. The day after the incident, Sara announced her resignation as chairperson from Lakas-CMD, the party that served as her vehicle for the vice presidency and where Romualdez serves as president while Arroyo is chair emeritus. In a statement that accompanied her resignation announcement, Sara said that her stay in office “cannot be poisoned by political toxicity or undermined by execrable political powerplay.”[viii]

Romualdez for his part did not dismiss the coup allegations. Instead, he said that moves to destabilize his leadership of the House should be “nipped in the bud”.[ix] Further fueling rumors of cracks in the House leadership, some power blocs in the lower chamber issued statements in support of Romualdez.[x] Thereafter, Romualdez, as President of Lakas-CMD, signed an “alliance agreement” with some of the biggest power blocs in the House. The total membership in the House of Lakas-CMD combined with political parties that signed the alliance is 234 congressmen. There are currently 316 seats in the House. Under the agreement, the parties pledged their “full and unqualified support” to Marcos Jr. and Romualdez “until the 19th Congress adjourns in 2025.”[xi]

This alleged coup attempt, though hushed and brushed swiftly under the carpet, hints at a falling out between factions within the Lakas-CMD party itself as Romualdez, Sara Duterte’s campaign manager in 2022, is now being revealed as a rival to her electoral prospects for 2028.

Arroyo, an indispensable Duterte ally

Arroyo’s relationship with the Dutertes runs deep. When he was still Davao Mayor, Rodrigo Duterte was one of Arroyo’s staunchest supporters during her presidency. In 2006, there was strong public clamor to have Arroyo ousted for her alleged involvement in the 2004 electoral fraud and multiple corruption cases. In response, Digong threatened to lead a separatist Mindanao rebellion, as he believed that unseating Arroyo would lead to more chaos and government breakdown.[xii]

Following her nine-year presidency, Arroyo was placed under hospital arrest during the term of Benigno Aquino III from the Liberal Party. But as many Filipinos became disillusioned with the Liberals, Arroyo saw her chance for vindication. She had publicly rallied support for the presidential bid of then Vice President Jejomar Binay in 2015.[xiii] However, Binay was being outpaced by another candidate, Grace Poe, who was on bad terms with Arroyo. It was Poe’s late father, Fernando Poe Jr, that Arroyo allegedly cheated during the 2004 presidential elections. Arroyo was thus desperate to have Binay win, as he seemed to be her only escape plan from her five-year-long arrest. That was, until Duterte came into the picture.

A latecomer to the presidential race, Digong’s ranking in opinion polls quickly rose, eventually surpassing his contenders by a huge margin two months before the elections. Digong, for his part, also courted Arroyo’s support. In one campaign rally, he said that if elected President, he would order the release of Arroyo.[xiv] And as it happened, on July 19, 2016, a few weeks after Digong was sworn in as President, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the dismissal of a plunder case against Arroyo.

Since then, Arroyo and the Dutertes have been exchanging political favors. During the beginning of his presidency, Digong initially had a flimsy footing in national politics, coming from the position of provincial mayor who was suddenly propelled to the highest post. He badly needed a well-connected power broker, and that was what Arroyo provided, helping him build a supermajority in Congress. Arroyo also tapped her international linkages, including Beijing. This influenced Digong’s pivot to China[xv] and resulted in the inflow of US$ 1.7 billion worth of Chinese investments into the Philippines during his term.[xvi]

Duterte’s daughter, Sara, also became involved in the political affair. In 2018, after Sara had a personal feud with then House Speaker Pantaleon Alvarez, Sara teamed up with Arroyo to oust Alvarez, and Arroyo took his place as Speaker. During the 2022 elections, Arroyo adopted Sara in her political party, Lakas-CMD, when the latter rescinded the political support of her father. The consolidation of the “UniTeam” coalition of prominent dynasties that supported Marcos and Duterte was also widely attributed to Arroyo.

The Bantag nexus

According to some political observers, another possible rift point between the Marcoses and the Dutertes is the Marcos administration’s handling of the murder and plunder cases against Gerald Bantag, former director-general of the Bureau of Corrections (BuCor), the government agency mandated with the custody and rehabilitation of national offenders.

In the murder case, Bantag is accused of being the mastermind behind the murder of journalist Percival Mabasa. A critic of both the Marcoses and the Dutertes, Mabasa was vocal about issues of corruption, red-tagging, disinformation, and the war on drugs.

Duterte had ties to Bantag and has even been linked to Mabasa’s murder. In September 2019, Duterte as President had fully endorsed the appointment of Bantag as BuCor chief. This became highly controversial at the time, as Bantag was then charged with homicide for allegedly planning a grenade explosion that killed 10 inmates during his time as warden in the Parañaque City jail in August 2016. The victims’ relatives claimed that the explosion was staged to kill inmates with drug-related cases.[xvii] According to Duterte’s personal aide Bong Go, Bantag was Duterte’s “personal choice” for BuCor chief. Go had previously told Duterte that a “killer” was needed inside BuCor to rid the New Bilibid Prison—the country’s main insular prison—of illicit activities, especially illegal drug trading.[xviii]

Ex-BuCor Chief Gerald Bantag and DOJ Sec. Crispin Remulla. Photos by CNN Philippines: https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2023/1/5/bantag-files-murder-misconduct-complaints-vs-remulla-others-before-ombudsman.html

Although there has been no concrete evidence tying Duterte to the Mabasa murder case, the court of public opinion has created linkages putting Duterte in a vulnerable position. After all, Duterte’s bloody drug war was among the subjects of Mabasa’s stinging criticisms. Duterte is also infamous for attacking press freedom. In a 2016 interview, he said that journalists are “not exempted from assassination” and “the Constitution cannot help” them if they defame someone.[xix] Under his presidency, at least 23 journalists and media workers were reportedly killed.[xx]

Another development pointing to the relevance of Bantag in the Marcos-Duterte dynamic is the filing of plunder, graft, malversation of public funds, grave misconduct, and dishonesty against Bantag. These were based on the allegedly anomalous bidding he led for the construction of various prison facilities amounting to about P1 billion, including one in Davao, the bulwark of the Dutertes.[xxi] Leading the filing of the charges was new BuCor Director Gregorio Catapang Jr., who was appointed by Marcos Jr. to replace Bantag after Bantag’s embroilment in the Mabasa murder case.

In the plunder and graft raps he filed, Catapang alleged that Bantag conspired with the other respondents to manipulate the outcome of the bidding process by creating a bids and awards committee (BAC) separate from that of BuCor. This new BAC then allowed the eligibility of the joint venture with CB Garay Philwide Builders and Rakki Corporation—a Davao City-based construction company—despite the companies submitting insufficient requirements.[xxii]

Shadows of the ICC

Photo from Amnesty International: https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2017/02/war-on-drugs-war-on-poor/

The sixth critical rift point between Marcos and Duterte is the Marcos administration’s handling of the International Criminal Court’s probe on Duterte’s “war on drugs.” Police records say that around 6,000 people have been killed under the campaign. However, human rights organizations put the number higher at 12,000 to 30,000. [xxiii]

After the ICC received a “mass murder” and “crimes against humanity” complaint against Duterte and 11 other government officials who orchestrated the drug war, the ICC began with a preliminary examination to determine if there is basis to proceed with an investigation. The ICC Pre-Trial Chamber authorized the start of the drug war investigation in September 2021. Two months later, the investigation was suspended upon the request of the Duterte administration, who claimed that it was conducting its own investigation. In January 2023, the ICC Pre-Trial Chamber authorized the resumption of the ICC’s drug war probe after finding the Philippine government’s investigations unsatisfactory.

The government—by then under the leadership of Marcos—submitted an appeal to the ICC in March 2023, asking the Court (1) to reverse its January 2023 decision to resume the drug war probe and (2) to suspend the investigation pending the resolution of the main appeal.

In February 2022, a House Resolution was filed by several representatives led by Gloria Arroyo to declare an “unequivocal defense” for Duterte against ICC investigations. In March 2023, the ICC Appeals Chamber rejected the Philippine government’s request to suspend the ICC probe.[xxiv] In response, Marcos said the government had no other recourse but to disengage from any contact with the ICC, given that “the appeal has failed.”[xxv]

This response is notable for two reasons. One, at the time that Marcos made the statement (i.e., March 2023), it was not true that the government’s appeal with the ICC had completely failed. Although the Appeals Chamber had denied the Philippines’ second request to temporarily halt the probe, it had not yet decided on the government’s request to reverse the January 2023 decision that reopened the drug war investigation (the ICC’s decision to reject this request only came in July 2023). Second, the Marcos administration’s disengagement with the ICC would not bode well for Duterte, as it would mean that the government will not submit any evidence to disprove allegations of abuse under Duterte’s anti-illegal drug campaign.[xxvi]

A point past convenience?

Vice Pres. Sara Duterte inauguration in Davao City attended by Pres. Fedinand Marcos Jr. Photo by ABS-CBN News: https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/06/19/22/sara-duterte-will-be-a-great-vp-says-marcos

Despite the brewing tensions, the “BBM-Sara” pair have strived to keep their relationship cordial, often portrayed in media as affectionate but platonic. Recently, Marcos even designated himself as Sara’s “BFF (Best Friend Forever)”. But besides the interest of maintaining the public image of a unified leadership, the power-sharing angle is an equally important statement to calm their supporters who have been at each other’s throats since the end of the electoral season. Marcos has also designated Duterte as OIC president during some foreign trips “to take care of day-to-day operations”, something he could have chosen not to do.

Marcos is also said to be hesitant to release former Secretary of Justice and Senator Leila De Lima from prison. De Lima has been a staunch critic of human rights violations committed during Rodrigo Duterte’s term as mayor of Davao and as president. In 2017, she was arrested and detained for being implicated in the New Bilibid Prison drug trafficking scandal. This has been widely denounced by human rights organizations and other international bodies as being politically motivated.

De Lima, a Pandoras’ Box for Marcos

In 2016, former president Duterte alleged that de Lima facilitated and benefitted from illegal drug trafficking in the New Bilibid Prison. Duterte’s accusations against De Lima came after De Lima initiated and led a Senate investigation into his administration’s campaign against illegal drugs. Even before becoming Senator, De Lima as former Justice Secretary had pushed for investigations on the alleged “death squads” in Davao during Duterte’s mayoralty. The Davao death squad has been described as a vigilante group that allegedly conducted summary executions of individuals (including street children) suspected of petty crimes and drug dealing.

With De Lima’s imprisonment being widely condemned by human rights groups as being politically motivated, her case has thus been repeatedly highlighted to illustrate political persecution under Duterte, with De Lima herself becoming a rallying figure for various human rights movements.

Last May 2023, De Lima was acquitted of drug charges in two of the three cases against her when state witnesses recanted their testimonies. Commenting on De Lima’s acquittal, Marcos’ incumbent Justice Secretary Crispin Remulla was quoted as saying that “the rule of law prevailed”.

Despite the acquittal, De Lima remains in detention pending hearings for her last drug charge and with courts ruling against motions for bail. The Marcos administration is said to be hesitant to release her despite prodding from a number of US senators owing to its not wanting to incur the displeasure of the former president.

For her part, Sara has been silent on issues where tensions could potentially arise between her and Marcos. For instance, despite the fact that her father’s future is hanging in the balance following the ICC’s decision to continue its drug war probe, Sara did not give any public comment on the issue.[xxvii]

Sara has also strived to project her loyalty to Marcos Jr. A clear demonstration of this is how she continued to express support for Marcos despite having a fallout with his cousin, House Speaker Romualdez, as a result of Arroyo’s demotion to deputy speaker. When she resigned as chairperson of Lakas-CMD, the party headed by Romualdez, Sara reiterated her commitment to serve the country “with President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. leading the way.”[xxviii]

Sara had also accepted the position of education secretary without protest (at least publicly) despite initially aiming for the defense portfolio. She was quoted as saying: “I expect that people who want to see the new administration fail will fabricate intrigues about my loyalty and the DND position to break the UniTeam.”[xxix]

However, it seems that Sara’s decision to not pursue the position of DND Chief was not without strings. This was revealed recently in the form of a Php125-million worth of “Confidential Fund” realigned from the Office of the President budget, to the Office of the Vice President (OVP). This illuminates Marcos’ continuing patronage to the Dutertes, as he had to use significant influence to compel the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) to approve the transfer of the said funds. The OVP was not supposed to have such funds in 2022 in the first place, since at the time Sara assumed the vice presidency in June 2022, her office only had to continue using the budget of her predecessor Leni Robredo, whose office did not request confidential funds for that year. It was later established that Sara sought confidential funds from the DBM, and the request was approved by the Office of the President. Critics have flagged the release of funds as unconstitutional since only Congress has the power to appropriate.

Upholding the traditional patronage values in politics is essential in maintaining power, lest one risk plunging the entire government into chaos. For Marcos, the 2022 win cannot be attributed solely to the effectiveness of his campaign machinery.

Why maintain unity?

Given the clear tensions and inherent contradictions between the Marcos and Duterte camps, the attempts of Marcos Jr. and Sara to maintain the image of a unified leadership begs the question: What’s in it for them? And is it still in their interest to maintain this tactical alliance?

Strategically speaking, one could say that it is in their best interest to maintain unity, that is, until such time that one gets ahead of the other in terms of political leverage and/or social capital. At this point in time, both Marcos and Duterte need something from each other to realize their respective political ambitions.

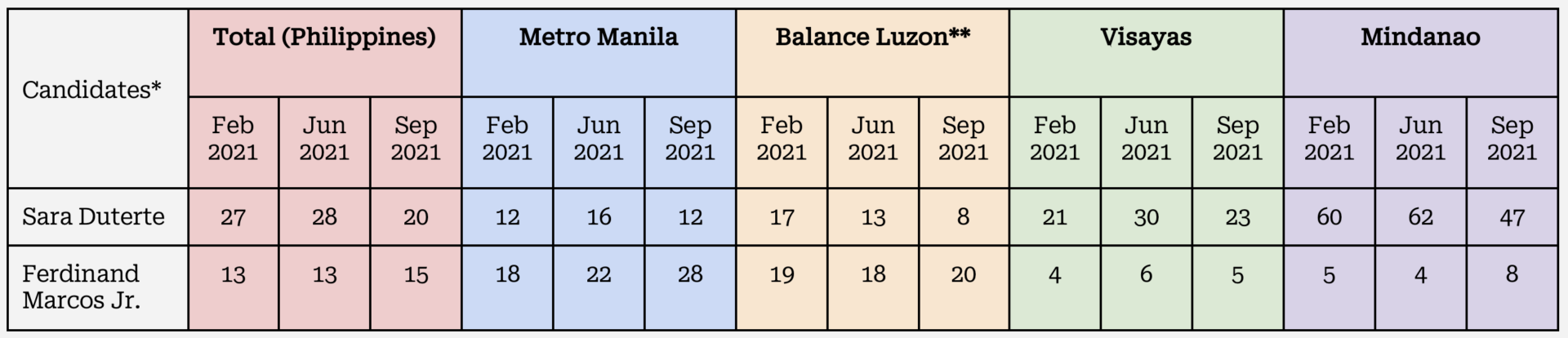

On the one hand, Marcos is careful to avoid any fallout with Sara, given that a significant part of his popularity was manufactured from the support that Sara mobilized from the South. Some analysts say that it was Marcos Jr. who benefited more from their alliance during the 2022 elections. Three pre-election opinion polls conducted by Pulse Asia in 2021 (February, June, and September) showed that Sara was consistently the top choice for president nationwide as well as from the vote-rich island groups of Visayas and Mindanao (see table below).

Table 1: Presidential preference for the 2022 elections

*Some 10 to 13 other names of hypothetical candidates were included in the final survey results of Pulse Asia. This table only includes Marcos Jr. and Sara for the sake of comparison. **Balance Luzon refers to the main northern region excluding the capital Metro Manila.

A survey conducted by opinion poller Pulse Asia in September showed that despite the sharp dip in approval ratings of both Marcos and Sara amid the persistent economic crisis, Sara still has the upper hand. Marcos’ rating dropped by 15 points, from 80 percent in June to 65 percent in September. Meanwhile, Sara still obtained a higher approval rating than Marcos, although it dropped from 84 percent in June to 73 percent in the September survey.

Sara’s popularity can be largely attributed to her father’s enduring massive support base. From a sociological perspective, while both Marcos and Sara’s popularity are underpinned by an anti-liberal rhetoric, the foundation of Marcos’ popularity is more abstract in that it relies on the promise of a return to an imagined “golden era,” which was popularized through a massive disinformation campaign that reinvented the Marcos patriarch’s legacy (which, in reality, was marked by violence and severe economic inequalities). Many of Marcos’ young voters have never really experienced this so-called “golden era.” Now, against the backdrop of an economy still reeling from the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic, inflation, job insecurity, unemployment, and insufficient wages, the lofty goals of the Marcos legacy cannot be sold to the public without the popularity of the Dutertes.

Compared to the abstract “politics of false nostalgia” that underpins the Marcoses’ popularity, Duterte’s “penal populism”—as suitably described by sociologist Nicole Curato[xxx]—is more contemporary, and the material conditions from which it emanated are felt more concretely by those who believe in it. For instance, many people claim to feel “safer” because of the “war on drugs.” The bloody campaign did not address the systemic roots of the narcotics problem and resulted in the death of thousands of people. But for many Filipinos, what matters is that it rid their streets of drug users who have long been relegated as second-class citizens, criminals, and social menaces in Filipinos’ collective consciousness. And in traditional politics, perception is what matters most.

Apart from the drug war, the Dutertes’ penal populism also emanates from their attacks against activists and human rights defenders. Owing to the previous Duterte administration’s propaganda that tapped into entrenched cultures of authoritarianism and individualism, advocates of social justice have come to be negatively perceived by many Filipinos as either destabilizers of peace and order or as social menaces who do nothing but demand entitlements from the government instead of working hard on their own to achieve better living conditions. Hence, the previous Duterte administration’s institutional attacks against human rights defenders has resonated strongly with the people. As part of the Marcos administration, Sara Duterte thus embodies the populist side of an otherwise traditional elite Marcos brand. For the Marcoses, the piper needs to be paid, at least for now.

But apart from Sara’s appeal to the masses, her political capital also emanates from her family’s influence over the Senate majority. During the 2019 midterm elections, nine candidates from Sara’s political party Hugpong ng Pagbabago (HNP) or Alliance for Change clinched seats in the Senate largely owing to Rodrigo Duterte’s endorsement.

However, Sara’s popularity currently hangs in the balance, as her office was recently embroiled in a controversy involving their questionable use of Php 125-million worth of confidential funds in 2022 in just 11 days. The rapid depletion of the secret funds could gravely diminish Sara’s popularity, especially in a context where millions of people continue to reel from joblessness, inflation, hunger, and poverty. Her most recent approval rating has not factored in this controversy yet, as the survey was conducted before the issue came to light. So the next survey could possibly see her popularity ratings dwindle, depending on how her camp handles the issue.

Meanwhile, Marcos’ approval of the OVP’s request for confidential funds in 2022 also entangled him in the controversy. He needs to play this right, lest he gets dragged further down by his involvement. Some of his cabinet members have already rushed to Sara’s defense. And perhaps to avoid fanning the flames, the Lower House had scrapped the confidential fund requests of the OVP, the education department headed by Sara, and other government agencies.

With Sara’s main leverage over Marcos now in precarity, she has all the more reason to be on his good side to avoid getting sidelined by the administration. After all, with the power and influence of the president, Marcos could simply cast her aside if she becomes more of a liability than an asset to him. The stakes are high for Sara, given that maintaining her relevance as vice president is her key to the presidency and to building her own political capital independent of her father’s fame.

Furthermore, as incumbent president, Marcos has access and control over resources that can be used to forge political alliances with more regional, provincial, and local politicians. The Marcoses’ ace in the hole is galvanizing the supermajority blocs in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, which came only a month after Marcos’ inauguration. Of course, at the onset, this was only made possible through the combined political capital of the “UniTeam”, and along with the forces aligned with the Dutertes and Arroyos. This event however prompted a political rigodon in congress where party hoppers were compelled to align themselves with the sitting President, knowing full well the resources that he wields. In a display of power, an astounding 283 (out of 340) representatives voted for Romualdez as House Speaker, along with Presidential son and Ilocos Norte 1st District Representative Sandro Marcos who was voted as the House senior deputy majority Leader despite being a neophyte.

House Speaker Rep. Martin Romualdez (L) shakes hands with Senior Deputy Speaker Rep. Gloria Arroyo at the beginning of the 19th Congress. Photo by Rappler: https://www.rappler.com/nation/recap-video-martin-romualdez-gloria-arroyo-update-house-tensions-may-22-2023/

Marcos and Romualdez have also shown what they can do to detractors (as evidenced by the demotion of Congresswoman Arroyo), and Sara must play her cards right if she wishes to avoid the fate of her political mentor. Furthermore, following the rumors of an Arroyo-led ouster plot against Romualdez, the House Speaker has managed to take hold of Lakas-CMD, and the party has forged alliance agreements with the biggest power blocs in the Lower House representing 213 congressmen.

Another show of Marcos Jr.’s political capital is when he ushered in 19 new members into the growing Partido Federal ng Pilipinas (PFP), the party that carried him in the race for the presidency last year. The PFP, established in 2018, is a political party formed by supporters of Rodrigo Duterte, and has been among the groups pushing for constitutional reform towards institutionalizing federalism in the country. Interestingly, included among those who were sworn in by Marcos as new members of PFP were governors from provinces considered Duterte strongholds.[xxxi]

Marcos Jr. said the PFP is preparing for all political cycles, including the upcoming barangay elections. As part of this, the PFP is now forging alliances with other political parties and seeking support at the barangay level. Such a move by the President and his party are crucial for consolidating political capital, as their ability to capture the barangay or village unit of government would translate to more grassroots support for the Marcoses during the midterms in 2025 and possibly the national elections in 2028.

Furthermore, a new political party has been formed, the Kilusan ng Nagkakaisang Pilipino (KNP), made up of several powerful political parties under the United Opposition that ran against Gloria Arroyo’s slate in the 2007 midterms elections. The KNP party’s leadership is formerly from Duterte’s PDP-Laban and could signal further deterioration of party memberships.

Intra-dynastic rifts or schemes for political survival?

While Marcos Jr. and Sara have tried to avoid alienating one another, there have been some noticeable rifts within their respective dynasties.

On the one hand, within the Marcos dynasty, there is an apparent friction between Bongbong Marcos Jr. and his sister, Senator Imee Marcos. This tension clearly surfaced when the siblings took different stances on the occasion of the People Power Revolution last February 25, which marked the 37th year since their father was ousted from power. While Bongbong said he was “one with the nation” in remembering the period and offered his “hand of reconciliation,”[xxxii] Imee said that she “can never stomach celebrating” the occasion.[xxxiii]

Apart from this, the Senator had also raised objections on a number of policy decisions made by her brother, including Bongbong’s veto of a bill to establish an ecozone in Bulacan province, his push for the controversial “Maharlika” sovereign wealth fund, his handling of food imports and rising inflation, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. Being an advocate of developing closer ties with China, Imee also disapproved of Bongbong’s decision to expand military cooperation with the US.[xxxiv] Most recently, in keeping with her penchant for political theatrics, Imee joined her “farmer and fisher friends” in a protest calling for the resignation of his brother’s finance chief, Benjamin Diokno, after Diokno proposed to eliminate tariffs on imported rice to curb surging rice prices.[xxxv]

Although they may certainly have disagreements, Imee’s antagonistic approach seems to be primarily part of a deliberate “good cop/bad cop” strategy that aims to safeguard the Marcoses’ political survival beyond Bongbong’s presidency. Journalist and sociologist Randy David had described it as a “political masterstroke,”[xxxvi] and rightfully so. The strategy requires experimentation, with Bongbong and Imee carefully testing out different policy approaches, strategies, and narratives, and identifying what resonates best with the majority. If it turns out that some (or majority) of Bongbong’s policies are unpopular, people would at least remember Imee as the big sister who was there to remind her brother of what he could have done otherwise, and ultimately, she would serve as the Marcoses’ safety net in case Bongbong falls out of favor.

On the other hand, within the Duterte dynasty, Sara and her father Digong had a highly publicized fallout in 2022 when Sara contradicted her father’s wishes and ran for vice president along with Marcos Jr. It remains unclear to this day if they have managed to bury the hatchet. But since becoming Vice President, Sara seems to have distanced herself from her father. This became clear when she refused to comment when asked about the ICC’s decision to investigate her father’s war on drugs or about his visit to Chinese President Xi Jinping without informing the Marcos administration.

Sara could have political motives for wanting to maintain distance from her father. Considering the uneasy history between Digong and the Marcoses, Sara perhaps sees the necessity of avoiding any direct political association with her father at this point in order to avoid suspicion and maintain the Marcoses’ trust. After all, Marcos Jr. still wields more power as President, and he can clip her wings if she gets on his bad side. The second motive of Sara is that she obviously wants to dodge any allegations of nepotism. Sara has always been sensitive about matters of her political independence. She has insisted on nurturing her own political capital and carving out a career for herself instead of just relying on her father.

However, Sara’s decision to take an independent course does not mean that she has completely abandoned her father. Her closest political ally and mentor, Congresswoman Arroyo, continues to maintain strong relations with Digong beyond his presidency. Arroyo led a group of 19 lawmakers in filing a resolution urging the lower chamber to defend Duterte from the ICC’s drug war probe. In September 2023, Arroyo met with Digong and courted him to return to politics, and possibly to run for Senator.

The Arroyo and Duterte camp publicized the meeting and even floated the idea of having Digong run for Senator in 2025. Days later, a survey commissioned by Publicus Asia came out saying that Digong emerged as the top choice for Senator. All these were perhaps publicity stunts, as Arroyo (and perhaps, by extension, Sara) is looking to gain an ally in the legislature after Marcos and Romualdez demoted Arroyo and captured the supermajority in Congress.

From the foregoing, it is clear that for both the Marcos and Duterte clans, what may seem like intra-dynastic rifts on the surface may in fact be strategies to ensure political survival. What lies at the center of these tensions may be just seemingly clashing but strategically complementary ideas on what would be the best course of action to preserve their respective dynasties.

The geopolitical equation

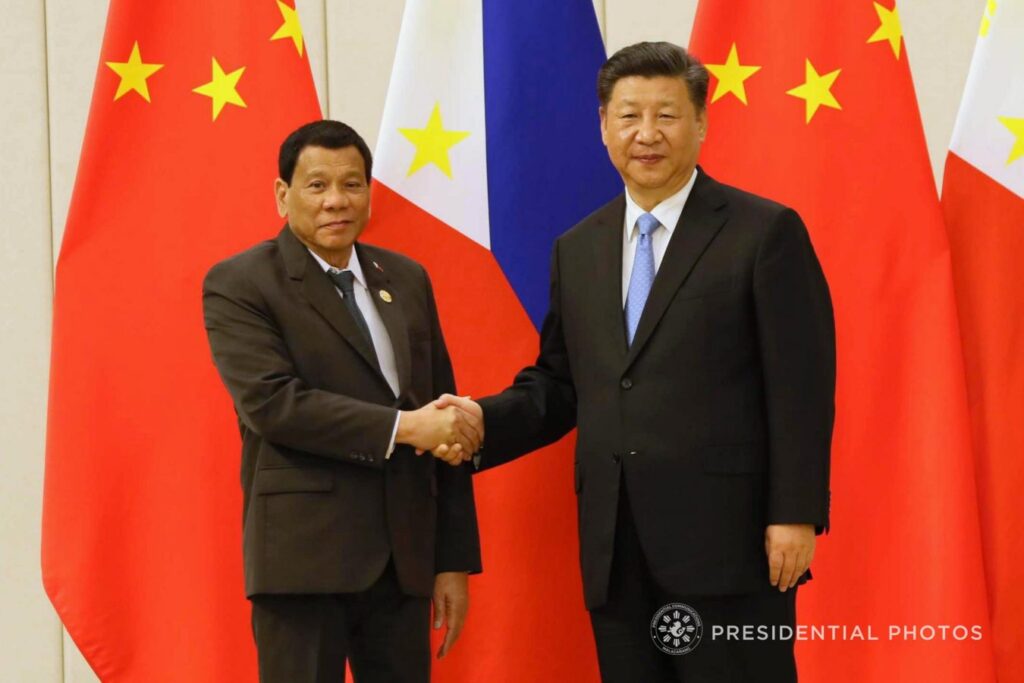

- President Rodrigo Roa Duterte and People’s Republic of China President Xi Jinping exchange tokens on the sidelines of the dinner hosted by the Chinese President at the Boao State Guesthouse on April 10, 2018. Photo by Ace Moradante: https://pcoo.gov.ph/photos/?post_id=64890

- President Joe Biden hosts a bilateral meeting with President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. of the Republic of the Philippines, Monday, May 1, 2023, in the Oval Office of the White House. Photo by Adam Schultz: https://www.flickr.com/photos/191819781@N02/52940482096/

Beyond the realm of intra- and inter-dynastic tensions and shifts, one critical factor that could significantly influence the outcome of the power dynamics between the Marcoses and the Dutertes is the growing tension between the US and China in the West Philippine Sea. Indeed, the dynamics between these two superpowers have become a critical driving force for developments around the globe. The Philippines has perhaps been one of the most (if not the most) entangled in the geopolitical tensions, largely owing to the archipelago’s strategic geographical location that could serve either the US or China’s security interests.

The Philippine leadership and its foreign policy are thus of paramount importance to both the US and China. With the quickly escalating tensions between the two and their desperation to control the Philippines, the Marcoses and Dutertes’ somewhat different foreign policy positions therefore becomes decisive in their respective pursuits for political survival.

During his presidency, Rodrigo Duterte was perceived as kowtowing to China as evidenced by his administration’s inaction on China’s territorial acquisitions and the many cases of harassment against Filipino fishermen by Chinese coast guard vessels. Beyond Digong’s presidency, he has maintained good relations with China. Last July, he skipped Marcos Jr.’s second State of the Nation Address (SONA) to visit Chinese President Xi Jinping instead. Marcos subsequently commented that his administration was not informed of the visit, but Duterte later met with him to tackle his meeting with China’s leader.

On the other hand, Marcos Jr. has moved dramatically closer to the US, away from Duterte’s foreign policy pivot to China. For his Defense Secretary, Marcos shunned Sara Duterte despite her being vocal about wanting the post, given that she was friendly with Beijing. Instead, Marcos appointed Gilbert Teodoro, a known champion of joint military exercises with the United States. In February 2023, Marcos signed an agreement allowing the US to occupy four military bases in addition to five it already operates. By August 2023, more sites were being eyed by the Marcos administration for the expansion of US-Philippine joint military training sites, especially in strategic areas near the WPS.

Apart from the US’ strong neo colonial influence in the Philippines, Marcos Jr.’s foreign policy direction—which foreign policy analyst Walden Bello aptly described as “blackmail diplomacy”—can also be attributed to his family’s personal stake in maintaining good relations with the western hegemon. Marcos Jr. himself has a standing $353 million contempt order (effective until 2031) related to a US court judgment awarding financial compensation from the Marcos estate to victims of human rights violations under the dictatorship. Furthermore, being cross with the US could also have devastating financial consequences for the Marcos dynasty, according to Bello. Currently, they hold some $5 to $10 billion worth of assets spread throughout the world. Given the US’ global influence, it could freeze these assets if the Marcoses become a liability, as it has done so in the past against people linked to regimes it considered undesirable.[xxxvii]

It is no secret that the US has a well-documented history of meddling with national political affairs in countries where it has entrenched economic and political interests. The US has been notorious for being involved—directly or discreetly—in coups and coup attempts around the world against regimes it found to be detrimental to its interests and installing pro-American leaders in their place.

At present, between the Marcoses and the Dutertes, the former would perhaps be the US’ preferred option. Although Digong poses no existential threat to US geopolitical interests as his anti-American posturing has been proven to be largely rhetorical, the US would strategically still want someone more predictable and controllable, and the Marcoses tick those boxes considering the leverage that the US has over them. In this sense, therefore, one could say that the Marcoses prevail over the Dutertes, as they have a more powerful backer and are depraved enough to exchange the Philippines’ sovereignty and security for their own political and economic survival.

Conclusion

The persistence of political dynasties, fueled by patronage politics remains a pervasive issue in the country, despite the desire among Filipinos to usher in a different kind of leadership, untethered from traditional, feudal and familial political structures. At the end of the day, the “change” everyone seeks come election season remains elusive, and the people are left with the same political players albeit packaged/branded differently.

The emergence of the Marcos-Duterte Uniteam brings together two prominent families known for their divisive and authoritarian tendencies, and raises serious concern on the future of democracy and human rights in the country. Both Marcos and Duterte, by invoking authoritarian nostalgia as the solution to the prevailing political, economic and social issues (i.e corruption, inflation and poverty), have actually reinforced the style of politicking that has made such issues persist. The Uniteam’s consolidation of power exacerbates further the erosion of checks and balances in government, and legitimizes the pursuit of personal/familial interests as the primary mover of political dynamism rather than pursuit of reform, leading the country towards a more oligarchic and exclusionary form of governance.

Political alliances are built and unraveled from the ambitions of players seeking entry into the ruling class. While the Marcos and the Duterte families, along with their stalwarts, supporters and factions mutually benefit from this alliance, both also possess considerable leverage over each other. Though they may maintain the status quo, when an opportune moment arises to elevate further or secure their stranglehold over positions of power, the Uniteam alliance, like many others in history, may quickly dissolve and turn into episodes of endless bickering or worse, violent power grabs.

The wheel turns slowly, but it turns. Disillusionment is gradually growing among segments of the right wing, especially those who were not seated in their “expected” places in government and the ones pushed into the sidelines by the political accommodation game played by the Marcos Administration. On the other hand, with worsening economic burdens and living conditions, segments of the population too are questioning if the Marcoses can aptly deliver on their promise of another golden era. The price is steep for ordinary Filipinos who are often undermined and deprived of potential policy and program developments when these power blocs in government collide.

Hence the spotlight must be extended beyond feuding dynasties to promote a new framework of governance that transcends dynastic control, and focused on addressing deep-seated social issues rather than political personalities. Survival in politics “depends on the climate” for politicians. But for the people, especially the marginalized, survival entails a shift in the entire political landscape by pursuing systemic alternatives to traditional politics, by demanding greater accountability, and by learning from the lessons of recent history.

Just as the Marcoses, the Dutertes and other dynasties have tapped into popular frustrations to win elections, it is also possible to harness people’s aspirations, such as securing decent living wages, accessible healthcare, affordable housing, the right to food to emerge with a new paradigm of governance, or to organize and mobilize around people’s calls and demands, moving beyond the influence of political dynasties.

References

[i] https://news.abs-cbn.com/spotlight/09/30/19/the-duterte-marcos-connection

[ii] Pursuant to Section 77 of the Philippine Omnibus Election Code, substitution of candidates is allowed only in cases of death, withdrawal or disqualification of the original candidate. In cases of withdrawal of the original candidate, the substitute can only file their Certificate of Candidacy within the period fixed by Comelec.

[iii] https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2021/11/19/Duterte-Bongbong-Marcos-weak-leader.html

[iv] https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1479066/sara-bongbong-tandem-in-2022-a-marriage-made-in-heaven-imee-marcos

[v] https://www.dbm.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/Our%20Budget/2023/2023-Budget-at-a-Glance-Enacted.pdf

[vi] https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2023/05/19/2267389/gma-demoted-house-senior-deputy-speaker

[vii] https://tribune.net.ph/2023/05/18/statement-of-former-president-gloria-macapagal-arroyo/

[viii] https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1771350/fwd-sara-duterte-resigns-from-lakas-cmd

[ix] https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2023/05/22/2268116/speaker-house-destab-must-be-nipped-bud

[x] https://www.rappler.com/nation/gloria-arroyo-denies-ouster-plot-against-speaker-martin-romualdez-may-2023/

[xi] https://www.rappler.com/nation/after-coup-rumors-lakas-cmd-alliance-agreements-house-power-blocs/

[xii] https://www.philstar.com/nation/2006/03/07/324774/duterte-push-mindanao-republic-if-gma-ousted

[xiii] https://www.rappler.com/nation/elections/124883-arroyo-marching-order-help-binay/

[xiv] https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/762270/duterte-if-elected-i-will-release-gloria-macapagal-arroyo

[xv] https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Calm-Arroyo-could-steady-passionate-Duterte

[xvi] https://thediplomat.com/2022/04/beyond-infrastructure-chinese-capital-in-the-philippines-under-duterte

[xvii] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XAocn2XTy94

[xviii] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ywVpvVG0o_Y

[xix] https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1690856/bato-defends-duterte-from-talk-linking-ex-president-to-percy-slay

[xx] https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/duterte-administration-blood-violence-drug-war-lawyers-activists-mayors-vice-mayors-killed/

[xxi] https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2023/02/07/2243165/bucor-files-p1-billion-plunder-graft-raps-vs-bantag-others

[xxii] https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2023/02/07/2243165/bucor-files-p1-billion-plunder-graft-raps-vs-bantag-others

[xxiii] Estimates by the ICC

[xxiv] See timeline of the ICC probe on the Philippines’ “war on drugs” here: https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2023/7/18/TIMELINE–ICC-s-probe-into-PH-drug-war.html

[xxv] https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2023/3/28/marcos-philippines-ending-involvement-with-icc.html#

[xxvi] https://www.cnnphilippines.com/news/2023/3/28/ICC-rejects-PH-appeal-drug-war-probe.html#

[xxvii] https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1803609/2-vp-sara-duterte-on-icc-probe-and-dads-visit-to-china-no-comment

[xxviii] https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1771350/fwd-sara-duterte-resigns-from-lakas-cmd

[xxix] https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1596683/fwd-embargo-sara-duterte-on-being-education-chief-ph-needs-patriotic-filipinos-advocating-peace-discipline

[xxx] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/186810341603500305

[xxxi] https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2023/08/25/2291138/marcos-swears-new-pfp-members

[xxxii] https://www.rappler.com/nation/marcos-jr-message-people-power-revolution-anniversary-2023/

[xxxiii] https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/inside-track/imee-marcos-skips-tan-ok-ni-ilocano-festival-ilocos-norte-2023/

[xxxiv] https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Marcos-is-gaining-fans-but-the-president-s-sister-is-not-one

[xxxv] https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/inside-track/imee-marcos-joins-protest-vs-bongbong-finance-chief-diokno-september-2023/

[xxxvi] https://www.thestar.com.my/news/focus/2022/08/21/bongbong-and-imee-sibling-rivalry-or-political-masterstroke

[xxxvii] Ibid.