by Bianca Martinez and Raphael Baladad

With contributions from Focus on the Global South – Food Sovereignty Team (Ranjini Basu, Ridan Sun, and Kheetanat Wannaboworn)

The Global Food Crisis, this time

A dossier by Focus on the Global South

A perfect storm is brewing in the global food system, pushing food prices to record high levels, and expanding hunger. The continuing fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine War, climate-related disasters and a breakdown of supply chains have led to widespread protests across the global South triggered by the spiraling food prices and shortages.

As international institutions struggle to respond, some governments have resorted to knee-jerk ‘food nationalism’ by placing export bans to preserve their own food supplies and stabilise prices. While this is an understandable defensive response, the solution lies in a more systemic, transformative approach.

In this dossier, researchers from Focus on the Global South write about various aspects of the current crisis, its causes, and how it is impacting countries in Asia. These include regional analysis, case studies from Sri Lanka, Philippines and India, the role of corporations in fuelling the crisis and the flawed responses of international institutions such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the Bretton Woods Institutions and United Nations agencies. We also attempt to present national, regional and global aspects of a progressive and systemic solution as articulated by communities, social movements and researchers at multiple levels.

Articles will be published every week till mid-October. Other articles included in the dossier can be found under this tag here.

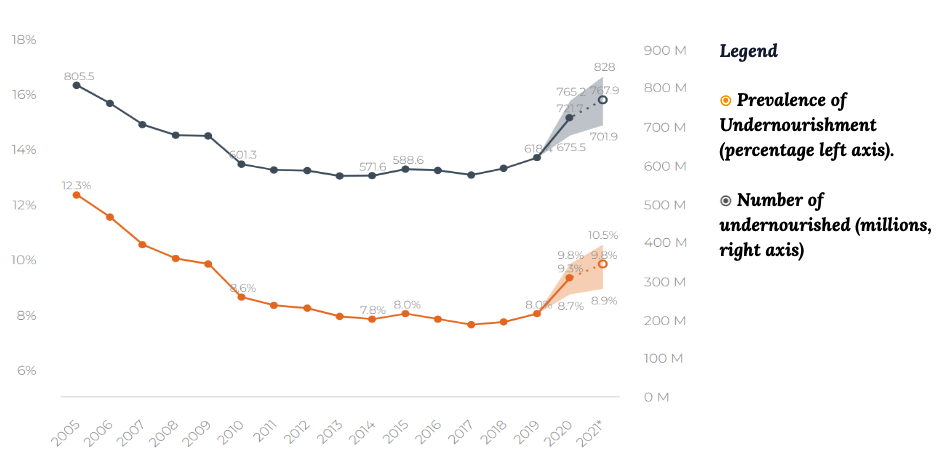

A food crisis, to define briefly, is a situation where hunger and malnutrition have escalated to alarming levels caused by the scarcity of food. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, global hunger and malnutrition became an even larger threat than the virus itself as global food supply chains collapsed, millions lost their jobs, incomes were drastically reduced, and economies went into depths of recession not seen in over a decade. According to the most recent State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) Report released by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), it was estimated that the number of people affected by hunger has increased by about 150 million since the beginning of the pandemic, with the total estimated to be between 702 million and 828 million. Of this number, 425 million are from Asia, making it the region with the highest number of undernourished people.[i]

Indeed, the pandemic served to accelerate the rate at which the world headed towards a food crisis that has been impending for the past decade. The root of the problem lies in the industrial food system itself. This paper will examine some of the structural problems that have been plaguing the global food system (particularly their manifestations in the context of South and Southeast Asia), and how these problems were magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russo-Ukrainian War, and the economic recovery programs implemented in the wake of these crises.

What this will show is that the system thrives on inequality and is thereby inevitably headed toward worsening hunger and food insecurity. But while the accrued impacts of multiple crises have brought the food crisis to greater heights, they have also revealed more clearly than ever before the unsustainability and irrationality of the industrial food chain. This provides an opportunity for social movements to highlight the importance of food sovereignty as an alternative and to create social pressure on governments and multilateral organizations to steer policies toward this direction. In light of this, the paper will also look at opportunities for harnessing national and cross-regional people-to-people solidarities in advancing food sovereignty.

I. STRUCTURAL ROOTS OF THE FOOD CRISIS

The pandemic foregrounded the systemic weaknesses of the global economy, which resulted from decades of neoliberal reforms and corporate-led globalization. Millions were infected, pushed into the deeper ends of poverty, and unnecessarily died of sickness and/or hunger due to enfeebled and highly privatized social services, particularly in healthcare, food assistance, and social protection.

The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that more than 81 million[ii] jobs were wiped out in the Asia-Pacific region. When urban economies shut down, there was mass migration back to rural areas, where jobs were already scarce and resource systems in distress.

Apart from the lack of available food supplies, poverty is seen as one of the greatest contributing factors to hunger. In the last two years under the pandemic and with the alarming rise in unemployment, around 4.7 million[iii] more people in Asia (from a pre-pandemic baseline of 203 million) have been pushed towards extreme poverty (living below USD 1.90/day), according to data from the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

With the restrictions in social mobility from the lockdowns, families have been forced to cope with unemployment by selling personal properties, borrowing, pawning, and reducing food consumption in order to survive. In response, governments have resorted to emergency cash transfers or food relief to alleviate hunger and malnutrition and to allow families to allocate dwindling incomes to other needs. But in many cases, the effectiveness of these interventions was undermined by the inefficient, discriminatory, and politicized delivery of aid.

As economies were slowly rebuilding from the pandemic, the public was slapped with new tax policies as well as surging inflation rates. Looking at Cambodia, Philippines, and Thailand in Southeast Asia and India in South Asia, inflation rates have spiked to an alarming 6 to 8 percent from 2021 to 2022. Although daily minimum wages have increased in these four countries, these were still inadequate to cover price surges in basic commodities including food. In India, several policymakers are urging the public to condemn food subsidies, thereby intending to end the Public Distribution System, detrimental to the survival of the poorest sectors. In Indonesia, the government recently imposed cuts on fuel subsidies, thereby increasing fuel prices by about 30 percent—the first hike in eight years—amid soaring inflation.[iv] Expected to hurt the most marginalized sectors, the fuel price policy has sparked mass protests involving students, labor unions, farmers, and fishers, among others.

It was against the backdrop of the pandemic and the economic recession that Russia invaded Ukraine at the end of February 2022. Considering Ukraine and Russia’s significant contributions to global agricultural trade, the war has disrupted the supply of crucial foodstuffs and farm inputs. Consequently, millions who are dependent on global food supply chains have been exposed to increasing food prices and severe food insecurity.

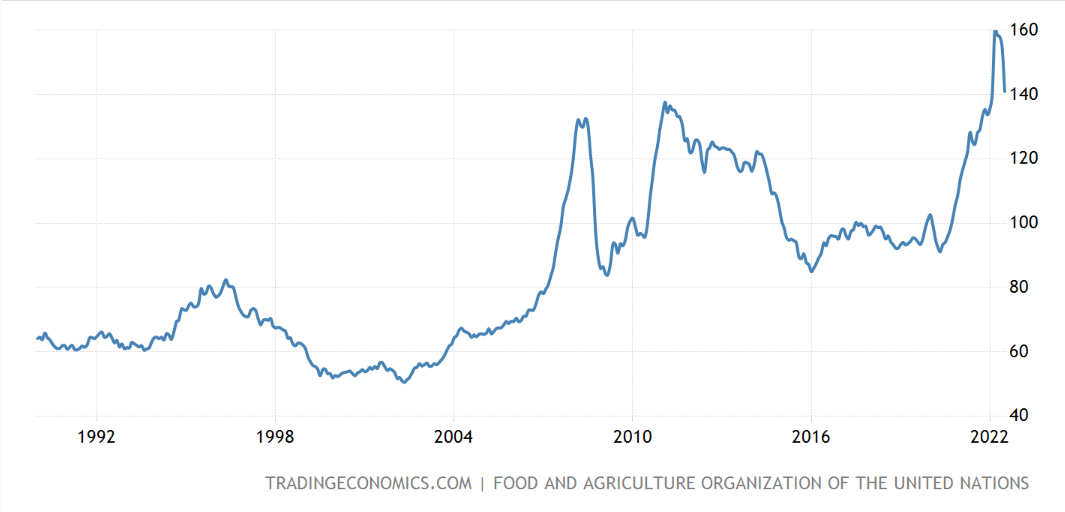

Food Price Index 1992-2022 Source: Trading economics: https://tradingeconomics.com/world/food-price-index

However, although Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is indeed an important trigger factor in the recent food price hikes, it is not the sole driver. The chart above from Trading Economics shows that since the 2008 global financial crisis, the FAO Food Price Index (FFPI) has not gone down to its pre-crisis levels. There was only a brief dip in 2016 before the FFPI rose again in the same year and shot up in 2020. Various analysts have proclaimed that the global financial crisis in 2008 was in fact the final thrust that brought an end to the era of cheap food.

Similarly, hunger has also been on the rise since 2018, as seen in the chart below from FAO.

Source: Food and Agriculture Organization: https://www.fao.org/state-of-food-security-nutrition/2021/en

The war and the pandemic have become convenient scapegoats by governments to account for the worsening hunger and poverty, but this narrative does not show the entire picture. In reality, these developments can be attributed to a confluence of factors, including the globalization and liberalization of agricultural trade, commodification and financialization of agriculture, the embeddedness of gender inequality across the industrial food chain, the climate crisis, and the systematic harassment and killings of peasants, farmers, workers, artisanal fishers, indigenous peoples, and women who struggle for their rights to land, water, and support for livelihood amid the intensifying push for a neoliberal agenda.

Globalization, liberalization, and commodification of agriculture

Well before the war and the pandemic, the intensive liberalization of agriculture and food trade had uprooted territorial food systems in favor of a more globally integrated one. This was initially introduced through structural adjustment programs (SAP) imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank on developing countries in the early 1980s. Integrated as conditionalities in loans offered to developing countries, SAPs systematically deprived domestic agriculture in Global South countries of state support and promoted agricultural liberalization and privatization.

Agricultural liberalization was then institutionalized in 1995 with the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the enforcement of the Agreement on Agriculture (AoA). With the WTO’s susceptibility to the influence of Global North, the trade regime it enshrined has largely favored the interests of wealthy countries and transnational corporations (TNCs). Trade and investment rules have primarily served to pry open South economies through liberalization. This is so that the North and TNCs could simultaneously extract the South’s resources (raw materials, land, labor, etc.) to lower their cost of production, while also allowing them to dump their highly subsidized food and agricultural products in local markets of developing countries.

Such dynamics have resulted in the displacement of territorially embedded food systems in the Global South. By undermining the capacity of various local communities in developing countries to produce their own food, the liberalization of the food and agricultural trade has made millions increasingly dependent on global food supply chains dominated by TNCs, agro-industrial and agritech firms, and food retail giants, among others. Ultimately, keeping developing countries dependent on food imports from the North is a central motive of the latter in sustaining the present trade regime, as it allows them to temporarily mitigate the crisis of overproduction/underconsumption in their own backyard.

The social cost of agricultural liberalization in India

India has been following a route of neoliberal policies in agriculture since the 1990s. The government spending on agriculture and food subsidy has been progressively declining over the years. For 2022-2023, the overall budget for rural India fell further from a measly 5.59 percent to 5.23 percent of the total Union budget. Given the fact that a substantial part of the population in India still relies on agriculture for their livelihoods, the budgetary allocations are disproportionately low.

In addition, land/agrarian reform policies of the Indian state have been almost abandoned in the post-liberalization period since the 1990s. Decreasing public spending in the countryside, the rising costs of cultivation, and the absence of policies that protect the rights of farmers/peasants subjected rural areas to various situations of agrarian distress. The number of farmer suicides has increased at alarming rates, and state forces are being mobilized against people’s movements that defend land, water, forest resources from corporate capture.

This was the cost of propelling an agriculture sector driven by an export-intensive economy, where local production has been programmed towards global trade. Though India is a food-surplus country, it has some of the highest hunger levels in Asia, according to the Global Hunger Index. In spite of this, the present government through the three Farm Laws intended to further liberalize agriculture in 2020. However, due to the historic and massive united protests by the farmers’ organizations, the government was forced to retract these policies.

The unabated desire for greater profits of corporations across the global food value chain has pushed many of them to consolidate horizontally and vertically. Consequently, big industry players “now constitute roughly 30 to 50 percent of the food systems in China, Latin America, and Southeast Asia, and 20 percent of the food systems in Africa and South Asia.”[v] According to activist-scholar Walden Bello, this monopolistic practice has strengthened corporations’ bargaining power, allowed them to control decision-making, and expanded their “capacity to extract rents from the chain to the disadvantage of the small-scale producers”[vi] (who are systematically pushed into conditions where they have no other choice but to either depend on meager incomes or be trapped in a vicious cycle of debt to survive).

Overall, the intensification of liberalization as well as the monopolization in agriculture point to the ever-deepening commodification of the sector. This is deeply connected with widespread land grabbing, the conversion of farmlands for non-agricultural use, and the diversion of agriculture from food production to the production of non-food products.

Institutionalized land grabbing in Cambodia

The surge in land grabs in Cambodia in recent years has been largely associated with the government’s unabated endowment of Economic Land Concessions (ELCs) to investors and corporations in the name of “economic development.”[vii] This is operationalized through the country’s 2001 Land Law, which allows the government to issue ELC leases of up to 99 years under the pretext of economic development.

In response to criticisms, Prime Minister Hun Sen has made several revisions to the country’s ELC policy. In 2012, his government issued a moratorium on ELCs, but this failed to significantly scale back land grabbing. In 2016, the state had reportedly revoked more than 1 million hectares of ELC land, thereby reducing it to around 1.1 million hectares.[viii]

But the reported gains from this effort were subverted as the government continued granting ELCs. December 2021 data from the Global Forest Watch shows that Cambodia has so far granted 302 concessions encompassing 2.2 million hectares of land, or 12 percent of the country’s total land area.[ix] Actual cases could be higher, as not all cases are documented.

Deforestation also remains an alarming problem in Cambodia. Much of this is enabled by large-scale commercial logging and smuggling, often done in collusion with corrupt government officials. Since 2000, the country has lost 26 percent or 2.3 million hectares of its forest cover, including the 63,000 hectares of forest lost in 2019 that made Cambodia the 10th highest in the world that year.[x]

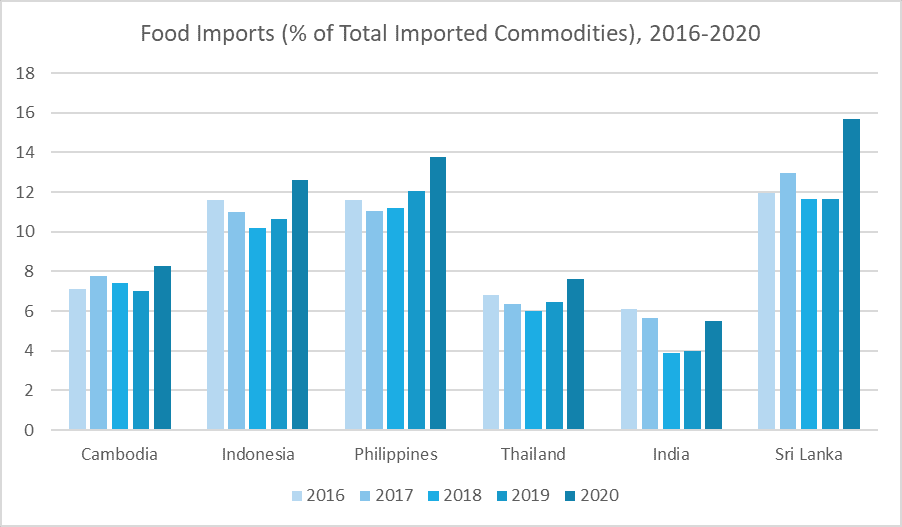

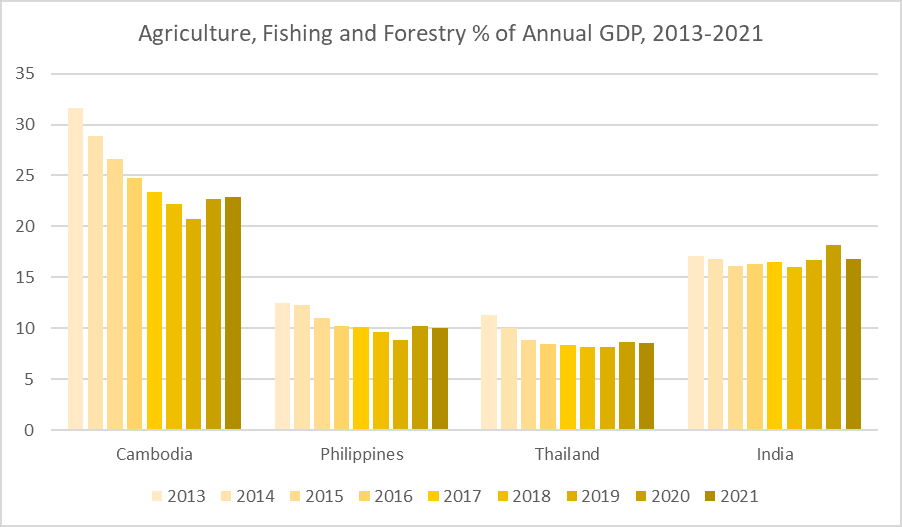

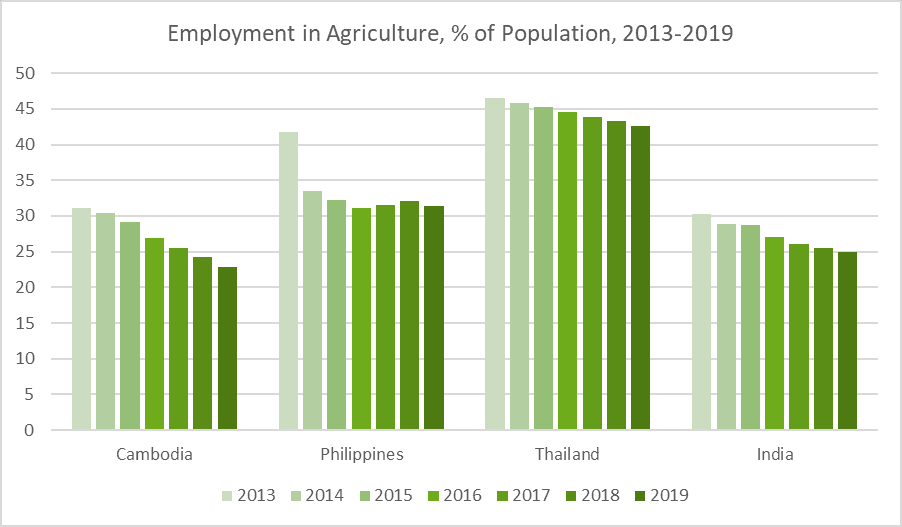

With the odds against smallholders in almost every aspect of the industrial food chain, it is not surprising to see a constant decline in agricultural productivity and more importantly, small-scale food production. In the last two decades, the region has seen rural-to-urban migrations at an alarming rate, where small-scale food producers would rather find employment elsewhere than risk further indebtedness in working their tillages. These trends are illustrated by the graphs below:

Source: World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/

Source: World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/

Source: World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/

Particularly in India, the land available for household operational holdings has been declining rapidly in the past 30 years[xi]. From 1991 to 1992, the land area under household operational holdings was 125.10 million hectares, while the total number of holdings was 93.45 million, thus making the average size of each holding 1.34 hectares. In the years 2018 and 2019, the total land available for household operational holding declined to 84.64 million hectares (or 40.46 million hectares lower than that from 1991 to 1992). However, the total number of holdings also declined to 101.98 million, indicating that during this period, many of the households have given up farming altogether. The average holding size has been reduced to 0.83 hectares.

In a situation where food security is threatened with shortfalls in supply, governments are quick to resort to importation, expanding minimum access volumes and lowering of tariffs, digging a deeper grave for small-scale food producers who are unable to compete with the influx of cheap food in local markets.

In the absence of adequate production support such as post-harvest facilities, farm to market roads, seeds, and other input subsidies—coupled with weak enforcement of land tenure policies and forest and fishing rights—peasants, farmers, fishers, forest dwellers and other people working in rural areas who produce 80 percent[xii] of the world’s food needs will not be able to prevent a food crisis from happening.

These developments have been brought about by the neoliberal capitalist logic of the industrial food system itself. In other words, the very logic by which the corporate food system is organized makes it inherently incompatible with food self-sufficiency and food sovereignty and ultimately geared towards creating food insecurity for millions.

Climate crisis

In addition to forcibly subsuming South economies to global agricultural trade, the industrial food chain also displaces locally and regionally integrated food systems by aggravating the impacts of the climate crisis. Recent estimates by the FAO indicate that agri-food systems[xiii] contribute 31 percent of the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions causing climate change. Of all the components that make up the food system, pre- and post-production processes along food supply chains have had increasingly significant contributions to emissions from 1990 to 2019.[xiv] These processes include manufacturing of fertilizers, food processing, packaging, transport, retail, household consumption, and food waste disposal. The report also shows that in 2019, corporate-dominated food systems in Asia had the largest contribution to emissions, followed by Africa, South America and Europe, North America, and Oceania.[xv]

That the Global North is ironically the lowest contributor in this aspect is explained by the fact that most of the high-emission operations of their food and agriculture TNCs have been offshored to the Global South. Furthermore, land-use change—which is recognized by FAO as one of the three key components in computing GHG emissions of food systems—has become more rampant in the Global South also largely due to the operations of these North-originating TNCs.[xvi] In other words, while emissions are mostly generated by TNCs originating from the North, they are attributed to the South, where the operations of these corporations are now based owing to the dynamics of globalization.

In 2021, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warned that the climate crisis has reached “code red for humanity”. This means that many of the drastic and destructive changes it has been causing are becoming irreversible. Now at 1.2°C, the world is fast approaching the internationally agreed threshold of 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels needed to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.[xvii] Should this happen, the world will inevitably head towards a catastrophic and irreversible state of the climate crisis that will manifest in drastic rise in sea levels, climate variability that will be experienced in the form of extremely volatile weather conditions ranging from severe flooding to equally severe and prolonged periods of drought, and the destruction of forests and watersheds. This will have deleterious impacts on agriculture, water resources, coastal ecosystems, urban infrastructure, human health, and food sovereignty.

Already, these catastrophic changes are being felt in many parts of the world. The latest IPCC report estimates that 3.3 billion to 3.6 billion people or 40 percent of the global population live in places that are highly vulnerable to climate change impacts. Ironically, these communities contribute least to the problem, and they also have limited resources to cushion the blows. Extreme weather conditions have led to the destruction of the livelihoods of poor and vulnerable communities, massive social displacement, and extreme conditions of poverty and hunger. Instead of providing assistance to disaster-stricken communities in their most destitute state, governments in connivance with large corporations have taken advantage of the vulnerability of these communities to usher in big businesses and extractive industries.

Deadly floods in Pakistan

In June 2022, a deadly flood ravaged Pakistan due to heavy monsoon rains一following a severe heat wave earlier in the year. The flood claimed the lives of more than 1,400 people, and displaced more than 40 million[xviii] in several provinces. According to the Pakistani government, at least one-third of the entire country was submerged in water[xix].

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres lamented that he had “never seen climate carnage on such scale”, while blaming wealthier nations for contributing to the tragedy[xx]. According to climate experts, the heavy monsoon rains were caused by rapid glacial melting in northern areas of the country and the intense warming of the Indian Ocean. The rainfall during the monsoon was 67 percent higher than its usual rate.

From recent reports, the floods caused an estimated USD30 billion in damages to personal property and public infrastructure, plunging the country deeper into an economic crisis at a time when it has not fully recovered from the impacts of COVID-19. Further, more than 65 percent of the country’s food crops were destroyed by the floods which also claimed around 45 percent of the country’s agricultural land.[xxi] Despite the outpouring of humanitarian aid/relief, the Pakistani government will have to rely on imports to prevent the exacerbation of hunger in the long term, but this will worsen the country’s external debt standing. According to various reports, food inflation in Pakistan before the deadly floods has already surged to 26 percent.

The corporate-dominated food system is clearly beleaguered by another inherent contradiction leading to its own demise. While it has proven to be extremely vulnerable in the face of catastrophic climate events, its operations—characterized by interminable expansion of value chains, intensive use of resources, and promotion of environmentally degrading production methods to increase yields—have served as major contributors to climate change. This is threatening small-scale food providers and their ability to feed themselves and others in ways that respect the environment, biodiversity, human and animal health, local traditions, and the rights of producers and consumers themselves. The 2021 IPCC report in fact estimates that another 75 million people could be added to the ranks of the hungry as a result of worsening climate change.[xxii]

Gender inequality and food insecurity

On top of the destructive impacts of the liberalization and commodification of agriculture as well as the climate crisis, women in particular are being further marginalized and exploited as a result of gender inequalities across the industrial food chain. The nonrecognition and undervaluation of women’s contributions to food production and the institutional barriers limiting their access to land and other resources are some of the leading causes of food insecurity globally. As we will see in the cases cited in this section, the deprivation of women’s rights as food providers is inseparable from the operations of the industrial food chain as it is necessary for increasing the profits of big players.

Most official statistics show that men dominate the agriculture sector, but these numbers may not accurately reflect women’s contributions. Women’s agricultural labor is often considered to be extensions of their household tasks and are not officially documented as work. The lack of recognition of women’s contributions in agriculture is rooted in the predominantly masculine conception of the occupation as well as the deeply entrenched patriarchal view that undervalues reproductive work, despite the fact that it provides the foundation for productive work.

But on top of domestic work, women also have equally important contributions in productive work. For instance, in the fisheries sector, they play the role of both fishers and industry workers—catching, raising, cleaning, processing, and marketing seafood. In farming, women play crucial roles in seed saving, land preparation, weeding, pulling of seedlings, transplanting, harvesting, and marketing of crops. Studies have also shown that women often take on the responsibility of managing incomes and household expenses.[xxiii] As such, given that poor women are increasingly pressured by their socioeconomic conditions to take on productive work on top of reproductive work, they tend to be overworked. In the case of Thailand where the standard working hours is 35 hours per week, 44.14 percent of women in agriculture work 40 to 49 hours per week, while 36.95 percent reported to work more than 50 hours weekly.[xxiv]

Despite women’s crucial contributions in agriculture, patriarchal traditions normalize the casualization and underpayment or nonpayment of their work, to the benefit of capital.

The feminization and defeminization of agriculture in India[xxv]

Even during the period that saw the feminization of agriculture in India, women continued to be employed predominantly in underpaid/unpaid and insecure work. One of the main drivers of the feminization of agriculture was the mechanization of work traditionally assigned to men in certain regions, which prompted them to move out of agriculture. Consequently, women’s share of labor in agriculture increased as they had to take on farm work that was left unmechanized on top of their care responsibilities, which have remained unevenly distributed.

Women were increasingly mobilized as agricultural laborers as they were “cheaper to higher.” They have often been employed in tasks paid on piece rates, such as picking produce. At the same time, the conventional assignment of household work to women necessitated them to take on flexible working hours. Hence, as more women were hired, greater casualization of agricultural labor also took place.

But in recent years, the further mechanization of agriculture has been reversing the trend of feminization. Since 2009, it has been observed that “the number of tasks done mainly or exclusively by women have shown a decline in labor absorption due to mechanization.” However, agricultural labor that needed expensive machinery or that had completely transitioned to piece rates continued to be done manually, considerably by women.

Indeed, the feminization and defeminization of agriculture in India have both been detrimental to women. At the nexus of both phenomena is capitalist agriculture’s incessant chase for profits, aided in this case by mechanization that has both instrumentalized and displaced women.

One of the consequences of the nonrecognition of women as farmers or agricultural laborers is that they are burdened with an additional structural barrier to accessing land and the resources tied to it. This is evident in the stark difference in land ownership between women and men. In the Philippines, as of December 2020, only 94,874 women held Emancipation Patents (EP) compared to 417,689 men. Meanwhile, only 622,841 women have been awarded with a Certificate of Land Ownership Award (CLOA) compared to almost 1.4 million men.[xxvi]

Although there are a number of national and international legal frameworks[xxvii] in place that aim to protect women’s land rights, the meaningful implementation of these are hampered by discriminatory laws and practices. For instance, land titling or registration programs that often assign ownership to the “head of the household” tend to favor men given that many households across Southeast and South Asia remain patriarchal, where women are usually regarded[xxviii] as secondary farm laborers rather than principal earners.

Women’s limited access to land also largely limits their access to equipment, credit, and extension services. Because they often lack legal titles to their lands, most women have no claim to compensation when their land is taken by an investor, corporation, or the government. This makes them more vulnerable to land grabbing, displacement, and exploitation especially during times of crisis.

All these structural gender inequalities were further compounded by the pandemic and various wars and conflicts. For one, women’s care responsibilities multiplied as workplaces and schools shifted to remote arrangements. Being the ones often tasked with managing household finances, women have also borne much of the stress of finding new sources of income amid the widespread loss of jobs and rising prices of basic necessities. On top of these, conditions created by the pandemic also magnified the risk factors of violence against women (VAW).[xxix]

The overlapping economic, political, and social crises faced by women made them and their dependents more vulnerable to food insecurity. According to the FAO, the 2021 gender gap in food insecurity reached 4.3 percentage points, with 31.9 percent of women in the world being moderately or severely food insecure compared to 27.6 percent of men. Poverty among women and girls is also expected to rise. It was estimated that, globally, 388 million women and girls will be living in extreme poverty in 2022 (compared to 372 million men and boys). But these are only moderate projections. In a “high-damage” scenario, the numbers could balloon to 446 million women and girls and 427 million men and boys. The forecasts also reveal that of the world’s extremely poor women and girls, 25 percent (or 100 million) would come from Central, Southern, Eastern, and Southeastern Asia.[xxx]

Authoritarian measures in aid of corporate interests

Many countries in Asia continue to be reported as the worst places for land, environmental, and human rights defenders. According to the most recent Global Witness report, 227 land and environmental defenders were killed worldwide in 2020, making it “the most dangerous year on record for people defending their homes, land, and livelihoods, and ecosystems vital for biodiversity and the climate.”[xxxi] Of the 228 who were killed, 40 came from South and Southeast Asia, with 30 in particular from the Philippines.

In some countries across South and Southeast Asia, the culture of impunity is in part enabled by the sweeping rejection of liberal democracy which has failed to deliver its promises of social justice as it ended up catering to the interest of the elites. With this rejection, many have turned to embrace authoritarian leaders, whose popularity usually derives from their being portrayed as the antithesis of the old and discredited approaches of elite democracy.

Emboldened by their popular mandate, these authoritarian leaders passed draconian laws that are enforced on the pretext of inflated emergencies concerning national security, but are in fact used to indiscriminately silence all critics and dissenters.

Intensification of lawfare in the Philippines

In the Philippines, the previous administration helmed by Rodrigo Duterte saw a dramatic rise in the indiscriminate tagging of government critics, activists, and human and land rights defenders as communist rebels and terrorists. The Duterte administration propagated the alarmist narrative that these individuals and groups were plotting to destabilize the government. Coming from this pretext, it enacted Executive Order (EO) No. 70 creating the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC) as well as the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) of 2020, which hinges on a vague and overly broad definition of terrorism that carries a serious risk of arbitrary application and abuse by authorities.

These legal frameworks served to institutionalize the repression, harassment, intimidation, unjust detention, and extended surveillance of those who are labeled as communists or terrorists—often without substantial evidence. Countless individuals included in the government’s list of communists and terrorists have already been captured, tortured, and/or killed.

In August 2020, just one month after the ATA was signed into law by Duterte, the first known ATA case was filed against two indigenous Aeta people from Zambales in the Central Luzon region: Japer Gurung and Junior Ramos. But according to Gurung and Ramos, they were only evacuating their homes to avoid being caught in the crossfire between the New People’s Army (NPA) and the military when they were arrested. The two were detained in August 2020 and were only acquitted almost a year later in July 2021 when the court ruled it was a “mistaken identity.” Before this, Gurung and Ramos had to endure a difficult legal battle, where they were caught in the grueling tug-of-war between, on the one hand, the government that created the despotic law, and on the other hand, human rights defenders and lawyers who have been trying to get the ATA repealed for its unconstitutionality.[xxxii]

Community leaders who are at the helm of struggles are often slapped with baseless criminal and civil lawsuits in multiple courts and government offices. The barrage of cases lodged against movement leaders often becomes an extra burden that diverts energies and limited resources away from the main campaigns and struggles. In India for instance, hundreds of cases were filed against protesting farmers during the course of the farmer’s protests from 2020 to 2021. When the government finally took back the farm laws and the farmers agreed to move from the Delhi borders, the central and state governments had assured that the police cases filed against the farmers will be taken back. However, even after many months, the cases are still to be rescinded.

Cases involving legal harassment, unjust detention, enforced disappearance, torture, and killing have become more widespread in rural areas and indigenous communities, where land conflicts arising from agrarian struggles, development aggression, and state and military occupation of land and territories have become increasingly prevalent. In Cambodia, large-scale and systemic land grabbing have resulted in a human rights crisis of colossal proportions. In a 2014 lawsuit filed in the International Criminal Court (ICC) against Cambodia’s ruling elites for “crimes against humanity,” it was estimated that 770,000 people—or six percent of the entire population—had been forcibly displaced as a result of land conflicts since 2000.[xxxiii]

Enforced disappearance and murder of environmental activist in Thailand[xxxiv]

Porlajee “Billy” Rakchongcharoen, a prominent ethnic Karen activist, was last seen in government custody at Kaeng Krachan National Park in Phetchaburi province in April 2014. © 2014 Human Rights Watch / Private

Porlajee ‘Billy’ Rakchongcharoen—ethnic Karen environmental activist—was last seen on April 17, 2014, in the custody of Chaiwat Limlikitaksorn, then-head of Kaeng Krachan National Park in Phetchaburi province, and his staff. Chaiwat claimed that they apprehended Billy for alleged illegal possession of a wild bee honeycomb and six bottles of honey. The park officials said they released him after questioning him briefly and had no information regarding his whereabouts.

At the time of his enforced disappearance, Billy was traveling to meet with ethnic Karen villagers and activists in preparation for an upcoming court hearing in the villagers’ lawsuit against Chaiwat and the National Park, Wildlife, and Plant Conservation Department of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. The villagers claimed in the lawsuit that, in July 2011, park authorities had burned and destroyed the houses and property of more than 20 Karen families in the Bangkloy Bon village. Billy was also preparing to submit a petition about this case to Thailand’s monarch. When he was arrested, he was carrying case files and related documents with him. Those files have never been recovered.

On September 3, 2019, the officials of the Justice Ministry’s Department of Investigation (DSI) announced that Billy’s remains had been found in Kaeng Krachan National Park. It was almost three years later, on August 15, 2022, when the Attorney General’s Office formally notified the DSI of its decision to indict four park officials, including Chaiwat, who were accused of abducting and murdering Billy.

The dire situation of human rights and social justice in South and Southeast Asia is expected to remain if not worsen. As we will see in the following section, governments, business elites, and international financial institutions (IFIs) are hellbent on maintaining the neoliberal order, even as multiple crises have exposed its fragility and unsustainability. This would have alarming implications on the state of democracy, which has already been backsliding in many countries in the two subregions over the past years.

By its very premise of prioritizing private profits over public welfare, the neoliberal capitalist system is inherently incompatible with social justice and human rights. For this reason, it also has the potential to ignite popular protests, especially when societies are pushed towards extreme conditions of poverty, hunger, and indebtedness. Now that many parts of the world are heading in this direction owing to the compounded impacts of the pandemic, wars, and the crisis of capitalism, the ruling class is expected to intensify their propaganda and use of violence to maintain the status quo. Authoritarianism becomes an intrinsic facet of the neoliberal agenda, especially where states have been captured by corporate interests.[xxxv]

II. BUSINESS-AS-USUAL RECOVERY PROGRAMS

Despite multiple and interlinked crises making the case for food self-sufficiency and food sovereignty, various governments, multilateral institutions, and IFIs under the influence of TNCs are insistent on maintaining the status quo. This is evident in their concerted efforts to reinforce global value chains, aggressively push for more debts to supposedly finance economic recovery, and give private interests more control over public policies and governance systems. All of these would inevitably further uproot territorially embedded food systems, facilitate more land and resource grabbing, and undermine the agency of small-scale food producers and low-income consumers.

Reinforcing global value chains

Various multilateral agencies and Northern governments have repeatedly cautioned about the importance of keeping the global food supply chains free from disruptions to ward off the food crisis amid the pandemic and Russo-Ukraine conflict. What they fail or perhaps refuse to recognize is that the global value chain itself has both precipitated and amplified the present crisis.

National governments have continued their pursuit of free trade agreements (FTAs) that seek to reinforce global value chains as one of the pathways to recovery. The most notable among such agreements is the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which entered into force in 2022 for the ASEAN countries, China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. The Philippines, the last country included in the treaty, is still currently deliberating its concurrence.

Amid the ratification of RCEP, civil society and social movements are striving to amplify their calls to reject this mega-trade deal because of its destructive impacts on local, small-scale food production.

Particularly on trade, the RCEP mandates the reduction or removal of tariffs imposed by each member state on various products. Depending on the category of the product, its tariff could either be immediately cut to zero (meaning, on the first day of implementation of the treaty) or gradually decreased through the years until it reaches zero or a level acceptable to the conditions in the agreement.[xxxvi] This means that cheap imported products (including those that are highly subsidized) would flood local markets, creating unfair competition for unsubsidized local food products. This would lead to massive losses for local small-scale food producers and small businesses that rely on them for resources.

The RCEP also weakens trade remedies that were previously enshrined in the WTO Agreement on Agriculture (AoA). In certain critical situations, trade remedies serve as the only legal recourse to address import surges and other problems engendered by freer trade. However, according to Raul Montemayor of the Federation of Free Farmers (FFF) in the Philippines, under the RCEP:[xxxvii]

Any form of quantitative restriction (QR)—like suspending sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) import clearances during harvest periods—is strongly discouraged…

RCEP limits the allowable safeguard duty to the difference between a country’s applied most favored nation (MFN) tariff at any point during RCEP implementation and the RCEP tariff in effect when the safeguard remedy is invoked. For example, if the applied MFN tariff for a product is 35%, and our tariff commitment under RCEP is down to 25% when an import surge occurs, we can only impose a safeguard duty not exceeding 10%. Hence, sensitive products like rice, corn, and some fishery and livestock products—to be exempted from any tariff reduction under RCEP—might ironically be deprived of any safeguard protection, since their tariff at any time during RCEP implementation could already equal their applied MFN tariff.

At the same time, the RCEP is also looking to further liberalize investments. In the interest of incentivizing cross-country investments, the agreement mandates that each government must give investors from other RCEP states the same treatment as domestic investors and allow them to purchase land.[xxxviii] This is inconsistent with land laws in most countries that only grant foreigners with leases, permits, or concessions with varying restrictions.

Such incentives would facilitate offshoring, thereby further stretching out the global food supply chain at the expense of food security and food sovereignty. At the same time, direct ownership of land by corporations could drive up land prices and speculation, thereby further pushing small-scale farmers out of agriculture. As seen in the cases cited in previous sections, corporate land grabbing and acquisition is already a huge problem in the region. Hence, fears that RCEP could intensify aggression against rural communities are not unfounded.

Burying the Global South in more debt

Over the last two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, the debt burdens of Global South countries have multiplied. With lenders aggressively pushing more debt as the solution to the multiple crises of public health, economic recession, food insecurity, and climate change, governments from the South ramped up borrowings supposedly to fund their pandemic responses. According to the Asian Peoples’ Movement on Debt and Development (APMDD): “Borrowings of low and middle-income countries in East Asia and the Pacific (EAP) region, and the South Asia (SA) region reached a record-breaking $1.23 trillion by end-2020 or almost their entire export earnings for the year.”[xxxix] Meanwhile, publicly guaranteed private debts have also risen, costing governments in EAP $51.4 million and those in SA $14.6 million in 2020.[xl]

Ballooning debt means more public funds will be diverted away from public services and social protection measures and towards debt servicing. In 2020, the World Bank estimated that debt service payments to IFIs and private lenders amounted to USD 115 billion.

Loans from IFIs like the IMF typically come with conditionalities in the form of austerity measures. These entail public spending cuts and privatization of basic services. Such measures undermine efforts to achieve national industrialization and protect social welfare, both of which are necessary for pursuing a fairer economy and addressing inequality. At the same time, austerity measures imposed by IMF loans also push governments to increase regressive consumption taxes and cap wages in the public sector, thereby shifting the burden of debt repayment on the mass of ordinary working people.

Clearly, structural adjustment loans and onerous debt servicing greatly hinder the ability of governments (especially in low- and middle-income countries) to recover from the overlapping impacts of multiple crises. These also undermine efforts to build more just, resilient, and self-sufficient economies. However, despite the widely recognized implications of the debt problem, the IMF and the World Bank are planning to “peddle more loans to crisis-ridden countries with limited options”:[xli]

The World Bank announced $170 billion in crisis response financing to be rolled out in 15 months, targeting to commit $50 million within the next three months. Much of this is expected to be loans though, just like the $200-billion COVID-19 crisis response from 2020-2022, of which only $23 billion of the $73 billion that went to IDA [International Development Association] were in the form of grants.

The IMF is also expected to continue embedding deleterious austerity measures in its lending programs as it did in the first year of the pandemic, during which it “promoted austerity in 85 percent of its financing response.” From March 2021 to 2022, “fiscal consolidation became requisite in 87 percent of IMF programs negotiated with developing countries.”[xlii]

The IMF and World Bank are also insistent on pushing through with debt repayments at a time when public debts of South countries have reached unprecedented levels and public funds are badly needed in welfare programs, social services, and social protection. The farthest these institutions could offer was a deferral of debt payments through the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) in 2020. Even then, the total deferrals granted were grossly inadequate: Only USD 12.7 billion worth of debt from 43 countries was deferred. The APMDD reports that this is “a paltry sum compared to at least $3 trillion estimated by the UN to help developing countries.” Furthermore, the DSSI had already ceased in 2021, and so low-income countries that were granted deferrals “now bear the full brunt of debt servicing in 2022.”[xliii]

Not surprisingly, there was no mention of more far-reaching measures such as massive reductions of outstanding public debts—starting with the cancellation of illegitimate debts—which broad sections of civil society have been demanding for decades. Instead, more destructive loans continue to be contracted under irregular and opaque procedures to finance projects that lead to widespread human rights violations, erosion of local livelihoods and displacement of communities, massive destruction of the environment, and exacerbation of the climate crisis and its consequences.

Bankrupt Sri Lanka ensnared by the IMF

In the case of Sri Lanka, unconditional bailout and cancellation of illegitimate debts is urgently needed to redirect resources towards social protection measures and reviving the economy. The country is currently enmeshed in its worst economic and financial crises yet. Across the island nation, living standards have taken a cliff dive due to severe shortage of fuel, cooking gas, energy, food, and medicines. In August, inflation for food items reached 94 percent on a year-on-year basis, while transportation costs had increased by nearly 150 percent.[xliv] Meanwhile, Sri Lanka’s debt-to-GDP ratio soared from 49 percent in 2019 to 111 percent in 2022. Borrowings went mostly into infrastructure projects that have gone bust during the pandemic. Up to USD 8.6 million[xlv] in debt payments are due this year, but the country only has USD 1.82 billion in its reserves as of end-July.[xlvi] The government was also supposed to settle USD 78.2 million as interest payment in April.

Amid the worsening economic and financial situation, the Sri Lankan government has been trying to negotiate a bailout with the IMF. On September 1, the two parties reached a preliminary agreement. Still pending approval from the IMF’s executive board, the deal would extend an emergency loan worth USD 2.9 billion in exchange for an “overhaul” of the country’s economy to reduce its fiscal deficits.[xlvii] The austerity measures that will surely be embedded in these new debts would inevitably result in heftier taxes for the masses and cutbacks in government subsidies.

Corporate capture of policy development

When food becomes profit-oriented, it also becomes a weapon for political control一 where government food policies are influenced towards the creation of more wealth in the hands of a few rather than addressing deep-seated issues such as poverty and hunger. The commodification of food and agriculture can largely be attributed to the corporate takeover of global food governance. This is facilitated by the consolidation of multistakeholderism as a governance model in the food and agriculture sectors. The multistakeholder approach has been progressively supplanting multilateralism, whose democratic potential as a governance system has consistently been undermined by the Global North.

Under the traditional state-centered multilateral system, governments as duty bearers deliberate and decide on global issues as representatives of their citizens, who are recognized as rights holders. These decisions then translate to obligations and commitments that states and international organizations are mandated to implement. Given that many governments are constitutionally mandated to work for the common good, they can be held accountable by their citizens when their decisions undermine public welfare and human rights.

Under multistakeholderism, the rights-based approach and direct lines of accountability at the core of multilateralism are discarded. This is because governments are no longer treated as the central decision-makers. Instead, so-called “stakeholders” become the main actors, even though there is no agreed-upon definition of a stakeholder and a standard procedure for designating one.[xlviii] Multistakeholderism is underpinned by the assumption that the common good will emerge when the varying (and often clashing) interests of different parties are balanced and negotiated. Theoretically, this means putting together governments, businesses, and civil society in one table to discuss critical global issues. However, as various critics have articulated, the treatment of diverse stakeholders as equals is problematic as it erases the very real inequalities in power and legitimacy of stakeholders on any given issue.

Hence, the idea of a balancing act is never fully realized in practice. The deeply political processes of identifying stakeholders and making decisions ultimately rest on those who have the most leverage in the space—that is, TNCs. Indeed, with TNCs consolidating their power owing to the institutionalization of neoliberalism and globalization, they were also able to capture various multistakeholder initiatives (MSIs). A mapping initiative of 27 agriculture-related MSIs by feminist activist researcher Mary Ann Manahan reveals that their key leadership positions are dominated by transnational agribusinesses, international/regional NGOs with ties to agribusiness, Northern aid agencies and governments, and interestingly, even food-related UN agencies.[xlix] The involvement of UN agencies in various MSIs has been widely criticized as being indicative of the increasing influence of corporations within these institutions. Meanwhile, Global South governments, small-scale food providers, and low-income consumers remain grossly underrepresented in various MSIs.

Such dynamics are a great cause for concern given that the outcomes of MSIs would take effect as policies. This is despite the fact that the actors that dominate these spaces and decide on policy outcomes have no direct accountability to the people that will be affected by their decisions. Given the dynamics within MSIs, global food and agriculture policies are becoming more skewed toward corporate interests.

Agribusinesses, big processors and traders, and supermarket chains and retailers have wielded their structural influence over food-related MSIs to shape policies and regulatory frameworks that purportedly promote development and sustainability. But in reality, these agendas are mostly directed toward increasing corporate profitability and control over resources and the global food economy rather than promoting just, democratic, and rights-based approaches to development.

The Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund

In the Philippines, the Rice Trade Liberalization Law (RTL) was passed in 2019, removing the Quantitative Restrictions in the importation of Rice. The passage of the RTL was led by a senator hailing from a family that owns one of the biggest corporations in the country. Their wealth amassed primarily from real estate and property development in rural areas.

Various land-based social movements have rejected this law as it threatens the livelihoods of local rice farmers who would be unable to compete with the influx of cheaper imported rice in markets. As a solution, the RTL had a Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund (RCEF) amounting to PHP 10 Billion (USD 175 Million) to be raised from tariffs and distributed as support to rice farmers annually.

In the same year it was passed, the Philippines imported 3 Million Metric tons of rice, surpassing China as the world’s largest rice importer. By amending the government’s supervisory functions over the rice industry as well as policy safeguards, the RTL also dissolved the state’s ability to stabilize the market. Ultimately it allowed importers and traders to flourish, and small-scale rice farmers to be pushed to further indebtedness.

Three years later, media reports and investigations claim that the RCEF was poorly disbursed. A huge chunk of its budget (PHP 6 Billion) went to mechanization projects where materials, supplies and equipment were acquired by the government from corporate distributors. Recently, the Philippine Senate began an investigation on alleged corruption in the purchasing of overpriced tractors by Department of Agriculture officials.

Various sustainability standards set by MSIs have been criticized for their inadequacy in addressing environmental and climate issues, heavy reliance on corporate partnerships, corruption, greenwashing, low standards of certification, and overly lenient third-party certifiers, among others. Meanwhile, policy-oriented MSIs have aggressively pushed for measures involving the reallocation of public financing for small-scale agricultural programs to large industrial growers, the privatization and heavily regulated use of waterways and irrigation canals for community farms, stiff penalties for the utilization and exchange of seeds protected by intellectual property, the preservation of “protected areas” delineated for carbon trading often resulting in the forcible eviction of agroforestry communities, and the aggressive push for energy infrastructure (in the name of “sustainability”) resulting in the massive displacement of rural communities. Gaps within policy frameworks designed to advance people’s rights and to protect their claims over land, water, and forest resources are widened further by neoliberal policy “reforms” that favor corporate interest over people-centered development.

In light of the emergence of new technologies, one recent false solution to the food crisis that has been advanced in Northern countries and is gaining ground in the South is the digitalization of agriculture. This was one of the main agendas advanced during the 2021 Food Systems Summit (FSS), an MSI notorious for being organized under the name of the UN but dominated by agribusiness and agri-tech firms. Although it did not create policies and global agreements directly, the FSS sought to define the path that governments will choose to prioritize, promote, and finance in the future, as well as those that they will reject. The Action Group on Erosion, Technology and Concentration (ETC Group) warns that the push for digitalization of agriculture in MSIs such as the FSS “could rapidly erase traditional knowledge about food production, thereby eliminating food sovereignty, and the independence and agency of farmers, smallholders, fisherfolk, and Indigenous people. This in turn could drive a process of agricultural de-skilling and aggravate rural-urban migration and associated societal woes.”[l]

III. OPPORTUNITIES FOR SOLIDARITY

Amid the onslaught of multiple crises of public health, conflicts, and economic recessions, millions lost their jobs and livelihoods and were left by the government without sufficient aid. But different communities took it upon themselves to help one another in the true spirit of solidarity.

One of the things that bound people together in these trying times was food. Travel restrictions disrupted the fragile global food supply chain, severing access to food for millions who have been forced by the system to depend on international trade for food security and livelihoods. In response, farmer communities from different provinces initiated or reinvigorated agroecological practices and seed banking and set up local markets to strengthen their collective resilience and food self-sufficiency. Some worked with civil society organizations to facilitate the delivery of their produce directly to low-income urban consumers. Across the region, grassroots-led community kitchens, pantries, and markets became the vanguard in the fight against hunger during the height of the pandemic.

These initiatives—juxtaposed with the dysfunctional food supply chains and the lack of timely support for those severely affected by lockdowns—have highlighted the importance of food sovereignty. Whether they are aware or not about what food sovereignty is, communities from different walks of life took it upon themselves to address hunger and malnutrition even in the simplest expressions, such as backyard and rooftop gardening. In some cases, these expressions have intensified public pressure for governments to enact policies and programs that support local food production.

Years before the pandemic, food sovereignty and related campaigns have been pushed with varying intensity and within various political spaces across South and Southeast Asia. These struggles are forged against the backdrop of unfair trade, absence of support from governments that have left food provision to the whims of the market, deep agrarian conflict, increasing threats to human rights, and other systemic issues. As such, they are often geared towards radical change and systemic transformation. Movements for food sovereignty have gained traction or waned over time, largely depending on the strength of communities in resisting forces, policies, or entities that undermine them.

Key to building this strength is increasing community awareness on the bundle of rights called for under the food sovereignty framework, along with the need to effectively claim or defend them. For this purpose, agroecology and seed saving play a crucial part in empowering communities to become more cohesive in responding to threats (i.e. cheap agriculture imports, land grabbing, displacement, indebtedness, and the climate crisis). These approaches also encourage solidarity and collective action within communities. By amplifying ecologically sustainable and culturally-appropriate methods in producing food, communities are able to reclaim their autonomy in defining food systems, re-embed food production in local and regional territories, and challenge profit-oriented models of rural development. By their recognition of the injustice of the corporate-dominated food system and the need to transform it, food sovereignty and agroecology as paradigm and practice are thus inherently political.

However, big corporations have for decades been attempting to depoliticize agroecology and appropriate it as a tool to greenwash the industrial food system, which has been under attack for its failure to address global hunger, massive GHG emissions, and rising production costs mainly due to the ecological degradation it causes to productive resources. In the face of such unscrupulous co-optation, grassroots movements must continue reasserting its transformative vision of agroecology and forge people-to-people solidarities across sectors and borders towards this end.

In Cambodia, various people’s movements are campaigning for agroecology to promote healthy food and preserve ecosystems in the context of increasing hunger in rural areas as well as widespread environmental distress caused by corporate mega infrastructure projects. The reliance on natural soil, seed, and forest resources is promoted to challenge the overdependence on chemical inputs, the prevalence of biotech crops and the dominance of industrial monoculture. Making independent choices on growing and raising livestock are promoted by community-led trainings on integrated farming systems and diversification. The production of natural fertilizers from livestock manure enabled family farms to reallocate more financial resources (e.g. debt repayments from the procurement of external inputs) to other livelihood needs. By relying less on external chemical inputs, small-scale producers also rely less on industrial seed varieties or hybrids that depend on them. Traditional seeds become more utilized as natural farming methods become more popular, leading to more community initiatives for seed saving. Rural movements in Cambodia have also pushed strongly for the right to build sustainable local markets that cater to community needs first and protected against cheap imports, opportunistic middlemen and consumerism.

In the Philippines, despite the dominance of agriculture policies that ultimately aim to integrate small-scale food producers to export-driven value chains, the push for policy reforms that place the right to food of communities first are gaining ground. Public pressure to support local agriculture and engaging local governance has become new arenas for advocacies on food sovereignty, in a context where national policies on food and agriculture have recently swayed towards the expansion of free trade as well as greater corporate control of food production and land use. In the face of worsening rural poverty, local movements push for the passage of key legislation, or the enforcement of policies that protect local food systems. The practice of agroecology, compelled by lessons from food inaccessibility during the lockdowns, is slowly becoming a key element sustaining struggles and campaigns (e.g. agrarian reform). This is alongside other community-led campaigns that demand for broader agricultural support services from the government in terms of production, education, and infrastructure, as well as the implementation of programs that safeguard farming communities against hunger and malnutrition.

In India, food sovereignty is an evolving concept that emphasizes roles of small-scale actors in food systems and their importance in increasing food diversity, including farmworkers, artisanal fishers, forest workers, migrant workers, pastoralists, food processors, refugees, and other vulnerable sectors/groups that are often sidelined in rural development discourses. While extreme poverty incessantly hounds the Indian countryside, government policies have continued to facilitate corporate capture of land, forest, water, and even plant genetic resources. Such measures have exacerbated hunger, malnutrition, and indebtedness, which have tragically pushed small-scale food producers towards committing suicide. In this context, food sovereignty has become a platform for empowerment to enliven small actors to push back against threats to livelihoods. Food sovereignty ensures small-scale food providers have effective control and the right to freely utilize all available resources for food production. It decentralizes power to local actors who are able to articulate their rights on decision-making processes of food policies. Various campaigns around food sovereignty have also pushed for policies that expand community rights according to gender, social class (e.g. the Dalits) and ethnicity, as well as to implement programs that enable various forms of redistributive justice. Agroecology has also taken center stage in rural movements, primarily as an alternative to conventional farming systems that aggravate poverty, but more importantly to rebuild historical, traditional and cultural knowledge in agriculture and food production.

In Thailand, campaigns on food sovereignty are seen as an impetus towards self-reliance in agriculture, where small-scale food providers are able to independently and sustainably manage and utilize resources within local food systems while prioritizing access, availability, and adequacy of healthy and nutritious food of marginalized communities. Movements for food sovereignty also aim at harnessing the collective energies of small-scale food providers through agroecology in restoring lost ecosystems and biodiversity from destructive farming practices (e.g. industrial monoculture) and to push back against land-financialization and corporate mega-infrastructure projects that threaten the survival of communities. Food sovereignty campaigns in Thailand also aim at enhancing autonomy in the management and preservation of other essential resources in food production such as seeds and plant genetics, livestock species, and technologies. This is—alongside influencing local governance and policy directions towards decentralizing food and natural resources management一commonly in the hands of rural elites and power holders. More importantly, food sovereignty movements seek to broaden traditional and culture-based knowledge in food production, considered by many communities that needs to be protected and bequeathed to future generations. This trend of reverting to traditional but more sustainable farming practices has also broadened toward northeast of Thailand and are actively being transferred to a younger generation of food producers. These efforts, alongside initiatives to deepen public awareness on the importance of rural communities for food security, create more links between producers and consumers, drumming-up involvement and support.

IV. CONCLUSION

From a human rights perspective, the criteria and indicators adopted by international bodies as well as governments in defining a food crisis remain largely market-oriented (i.e., narrowly grounded on maintaining the steady flow of international trade). They thus fall short in painting the multiple and interrelated crises that are aggravating hunger and poverty at the grassroots level.

As such, the present situation—despite being defined by spikes in food prices not seen since the 2008 food crisis, the displacement of territorially embedded food systems, and the rise in global hunger, malnutrition, and food insecurity—have not raised enough alarm to compel governments to allocate resources and adopt much-needed policy responses towards radical systemic reforms.

The solutions peddled by proponents of neoliberalism have not achieved the development outcomes needed to address severe hunger一not before nor after the pandemic. In contrast to neoliberal capitalist systems that subsume food production and consumption to the dictates of the market, the chief thrust of campaigns on food sovereignty is to ensure that communities can determine what they produce, provide, or consume according to their needs. In responding to the increasing threats posed by liberalization to local food systems, building awareness on the bundle of rights (i.e. land, resources, traditions) under food sovereignty is essential in breaking away from the grip of the food crisis. This is seen as key by various movements across the region in building a broader resistance against corporations, government policies, or even market forces that undermine community rights. In solidarity, peoples’ movements are able to reclaim power, enabling them to generate pressure in governance and exercise influence within policy narratives on food.

The call for systemic change should have the same intensity with the call for solidarity, especially as communities face compounding threats reinforced by neoliberal forces and the erosion of civil and political rights. Beyond the local purview however, a steady effort to engage international platforms and movements is essential as well towards building support networks that aid in strategizing campaigns, amplifying wisdom and experience, in generating public pressure, in exacting accountability, and in responding to violations of rights.

The international movement for food sovereignty plays a pivotal role in synergizing initiatives and campaigns at the local, national, and regional levels to advance different articulations of food sovereignty. Among others, it could:

-

- Provide support to movements in terms of understanding how the dynamics of the global political economy affects national level policies, which in turn have implications on their lives and livelihoods;

- Document and amplify critical community perspectives on the mainstream development agenda on food that has been propagated by those in power;

- Coordinate and strengthen grassroots-led campaigns that fight systems which undermine food sovereignty and ravage ecosystems as well as the agents that prop up these oppressive systems;

- Popularize interrelated alternative systems (such as food sovereignty, agroecology, deglobalization, degrowth, etc.) at a time when the legitimacy and relevance of mainstream development agendas are being put to question once again and the public is becoming more open to alternatives;

- Organize and mobilize traditionally untapped communities around the principles of these systemic alternatives;

- Facilitate spaces for cross-sectoral, cross-country, cross-regional, and cross-generational exchanges of knowledge on (1) practices of food provision grounded on the principles of food sovereignty, as well as (2) campaign strategies in terms of advancing the right to food, land, water, and other resources;

- Sustain spaces for learning and exchanges, with the recognition that knowledge and experiences constantly evolve in response to changes in contexts;

- Support lobbying for progressive policies that seek to advance and promote food sovereignty at the local, national, and regional levels; and

- Exert all necessary effort and resources to open up spaces for the meaningful participation of social movements and grassroots communities in crucial decision-making processes involving agriculture, food, and interrelated concerns at the international and regional level.

Building solidarities however is a challenging feat that requires transformative actions or exchanges to find common grounds and facilitate openness despite ideological and methodical differences among movements. Food sovereignty is not just a paradigm for a better food system, but also a space for uniting communities and movements, sharing the same struggles despite the diversity of issues in the food discourse. Its framework has no clear-cut method in campaigning, but it provides strategic directions and goals that movements can pursue in asserting peoples’ rights.■

[i] FAO et al., State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) (Rome: FAO, 2022) p. 10, https://www.fao.org/3/cc0639en/cc0639en.pdf. Accessed August 10, 2022.

[ii] “81 million jobs lost as COVID-19 creates turmoil in Asia-Pacific labour markets,” International Labor Organization, December 15, 2020, https://www.ilo.org/asia/media-centre/news/WCMS_763819/lang–en/index.htm. Accessed September 6, 2022.

[iii] “COVID-19 Pushed 4.7 Million More People in Southeast Asia Into Extreme Poverty in 2021, But Countries are Well Positioned to Bounce Back — ADB,” Asian Development Bank, March 16, 2022, https://www.adb.org/news/covid-19-pushed-4-7-million-more-people-southeast-asia-extreme-poverty-2021-countries-are-well. Accessed September 7, 2022.

[iv] “Protests in Indonesia as anger grows over fuel price hike,” Al Jazeera, September 6, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/9/6/protests-in-indonesia-as-anger-grows-over-fuel-price-hike. Accessed September 12, 2022.

[v] Walden Bello, “The Corporate Food System is Making the Coronavirus Worse,” Foreign Policy in Focus, April 22, 2022, https://fpif.org/the-corporate-food-system-is-making-the-coronavirus-crisis-worse/. Accessed September 5, 2022.

[vi] Walden Bello, ‘Never Let a Good Crisis Go to Waste’: The Covid-19 Pandemic and the Opportunity for Food Sovereignty, Transnational Institute and Focus on the Global South, April 29, 2020, https://www.tni.org/files/publication-downloads/web_covid-19.pdf

[vii] Clara Mi Young Park. October 4, 2018. “Our Lands are Our Lives”: Gendered Experiences of Resistance to Land Grabbing in Rural Cambodia. Feminist Economics, 25(4): 21-44. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13545701.2018.1503417

[viii] RFA Khmer Service, “Cambodia’s Land Concessions Yield Few Benefits, Sow Social and Environmental Devastation,” Radio Free Asia, August 26, 2020, https://www.rfa.org/english/news/cambodia/concessions-08262020174829.html. Accessed August 15, 2022.

[ix] Global Forest Watch, “Cambodia Land Concessions,” updated December 17, 2021, https://data.globalforestwatch.org/documents/d6c101b4a0134db1a0ed6037b12c95ac/explore. Accessed August 15, 2022.

[x] RFA Khmer Service, “Cambodia’s Land Concessions Yield Few Benefits, Sow Social and Environmental Devastation”

[xi] Based on Annual Survey of Industries from the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) in India

[xii] “Small Scale Farmers and Peasants Still Feed the World,” ETC Group, January 31, 2022, https://www.etcgroup.org/content/backgrounder-small-scale-farmers-and-peasants-still-feed-world. Accessed September 5, 2022.

[xiii] Agri-food systems emissions were estimated by FAOSTAT by adding the emissions from the following activities within the system: (1) farm gate (from crop and livestock production processes including on-farm energy use), (2) land use change due to deforestation and peatland degradation, and (3) pre- and post-production processes (including manufacturing of fertilizers, food processing, packaging, transport, retail, household consumption, and food waste disposal). See: https://essd.copernicus.org/preprints/essd-2021-389/essd-2021-389.pdf

[xiv] Francesco N. Tubiello et al. 2021. Pre- and post-production processes along supply chains increasingly dominate GHG emissions from agri-food systems globally and in most countries. Earth Systems Science Data. https://essd.copernicus.org/preprints/essd-2021-389/essd-2021-389.pdf

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] FAOSTAT data in fact shows that in 2019, emissions from deforestation were the single largest emission component of agri-food systems. See: https://essd.copernicus.org/preprints/essd-2021-389/essd-2021-389.pdf

[xvii] “Secretary-General’s statement on the IPCC Working Group 1 Report on the Physical Science Basis of the Sixth Assessment,” United Nations Secretary General, August 9, 2021, https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/secretary-generals-statement-the-ipcc-working-group-1-report-the-physical-science-basis-of-the-sixth-assessment. Accessed September 11, 2022.

[xviii] Zahid Gishkori, “Deadly floods: 70M Pakistanis affected, 170,000 sq km inundated,” Samaa, September 3, 2022, https://www.samaaenglish.tv/news/40016213. Accessed September 12, 2022.

[xix] “‘Never seen climate carnage’ like Pakistan floods, says UN chief,” Al Jazeera, September 10, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/9/10/never-seen-climate-carnage-like-in-pakistan-un-chief. Accessed September 12, 2022.

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Kugelman, M., “Pakistan’s Flood Crisis could become a Food Crisis”, Foreign Policy (FP), September 2022, https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/09/08/pakistan-floods-food-security-crisis/ Accessed September 10, 2022

[xxii] UN-OCHA, “IPCC report highlights urgent need to fund measures to protect world’s poorest from impact of climate change” February 2022, https://reliefweb.int/report/world/ipcc-report-highlights-urgent-need-fund-measures-protect-world-s-poorest-impact-climate Accessed August 12, 2022

[xxiii] Sonia Akter et. al.. May 18, 2017. “Women’s Empowerment and Gender Equity in Agriculture: A Different Perspective from Southeast Asia.” Food Policy 69: 270-279. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919217303688. Accessed August 14, 2022

[xxiv] “Women Workers Everywhere Work Hard.” National Statistical Office hailand. Accessed August 14, 2022. http://www.nso.go.th/sites/2014en.

[xxv] Focus on the Global South, “Women in Agriculture: Challenges and the Way Ahead,” August 2019 https://focusweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Women-Ag-report.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2022

[xxvi] Galileo Castillo, “Grey Economy and Sickly Recovery: Informal Women Workers in Pandemic-Ravaged Philippines”, Focus on the Global South, March 2022. https://focusweb.org/grey-economy-and-sickly-recovery-informal-women-workers-in-pandemic-ravaged-philippines/ Accessed August 14, 2022

[xxvii] Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. “Gender and Land Rights Database: Country Profiles”. UN-FAO. n.d. https://www.fao.org/gender-landrights-database/country-profiles/en/ accessed August 12, 2022

[xxviii] Roberts, R. Richardson, M. “Modern Women and Traditional Gender Stereotypes: An Examination of the Roles Women Assume in Thailand’s Agricultural System” Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347711850_Modern_Women_and_Traditional_Gender_Stereotypes_An_Examination_of_the_Roles_Women_Assume_in_Thailand’s_Agricultural_System Accesed from the Research Gate Website August 23, 2022

[xxix] UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, “The Covid-19 Pandemic and Violence Against Women in Asia and the Pacific”, June 2021, https://reliefweb.int/report/world/covid-19-pandemic-and-violence-against-women-asia-and-pacific. Accesed from ReliefWeb August 26, 2022